Now, I guess a viewer could just stop right there and save themselves about an hour and change. But! Nope. We are here for the duration. Thus and so, and here we go:

Once this evil alien despot is done bloviating, giving way to a fairly nifty, artistically rendered credit sequence (-- again, bad sign when your opening credits turn out to be the most interesting part of your movie), we cut to the story proper, which begins near the deserts of rural California on a parched farm, where the owner, Alan Kelley (Birch), barely ekes out a living raising dates with his wife and daughter.

Overwhelmed these last few days by a projected sense of dread and a strange malfeasance lingering in the air, Alan returns home after a hard day’s work only to resume a running argument with his wife, Carol (Thayer), over the future of their daughter, Sandy (Cole). And while the father insists Sandy will go to college, the mother counters, saying they can’t afford it. And by the time she gets to the “Well, I never went to college” verse, we get to the real reason for this open hostility as Carol finally confesses as to why she’s been so upset lately.

Stuck in a dead-end marriage in the middle of nowhere, Carol is terribly jealous of the opportunities Sandy will have that she never got -- even to the point of resenting and even hating her daughter for this. Then, realizing Sandy has overheard this spleen-venting, Carol tries to apologize for that last remark but now no one is listening.

Seeing her apology is going nowhere, Carol quickly shifts the argument toward Carl (-- though he’s referred to mostly as “Him” during the film), a mentally handicapped mute who had served with Alan during the war, I think, and suffered a traumatic brain injury. Both she and Sandy find him creepy and uncomfortable to be around as he works for them as a hired hand. But Alan refuses to let him go over some sense of obligation that is never properly explored, insisting the man is harmless.

Well, maybe, maybe not, as this latest argument concludes with Carol scolding and chasing Duke, Sandy’s dog, out of the house, who has managed to figure out how to open the screen doors. And so, Sandy, still feeling the sting of her mother’s harsh words, gathers up the chastised dog and storms off to the swimming hole, where Carl has followed and now watches her from the bushes until he is caught. Scolded for being a peeping tom, the man skedaddles.

Meanwhile, back at the house, we learn the only thing Alan and Carol can agree on is that the strange feeling emanating from the surrounding desert is at least partially responsible for their current woes. And it’s not “just the loneliness, and isolation; there’s something more, something actively malignant working to bring out the worst in them.” And here, Carol confesses if Sandy does go away, leaving her all alone out here, the woman is convinced she’ll lose her mind.

But Alan, ever the dunderhead, pushes this no further, shrugs, and goes back to work. After he’s gone, a shrill, high-pitched whine grows louder as something airborne gets closer until it blows by over the house, and whose intense pitch and backwash shatters most of the windows and breakables in the home, including Carol’s precious family heirloom china.

Assuming a low-flying jet from a nearby airbase is to blame, a furious Carol calls the Sheriff to report it; but this quickly goes nowhere.

Meantime, Alan is startled when a blackbird slams into the windshield of his car. Stranger still, when he gets out to examine the carcass, a whole flock of blackbirds attack, forcing him to flee.

After outrunning these belligerent birds, Alan stops at a neighbor's farm. There, Ben Webber (Conklin) listens to his strange tale and then relates how his milk cow, Sarah, has been acting strangely lately, too, but chalks it up to that low flying mystery jet putting her on the prod.

On the way home, Alan picks up Sandy, who lost Duke at some point and can’t find him. However, the audience knows where Duke went, as he’s followed a familiar high-pitched humming to its source:

At the bottom of an impact crater further out in the desert, a strange metal object lies half buried in the sand at the bottom (-- which we're not gonna reveal just yet, even though the movie does). And then the humming starts to get louder as the machine starts to glow, which has an extremely negative effect on the dog.

Back at the house, Alan and Sandy take in the damage and try to console Carol, who is having none of it; her mother’s irreplaceable china appears to be the last straw for her.

Then,

Deputy Larry Brewster (Sargent) shows up to check on the

reported damage and, after making sure his girl, Sandy, is okay, they

head back into town together.

Spying on all of this, a jealous Carl has a violent fit but drops his ax after Sandy calms him down. The girl is wary of the brute, but since he is sweet on her Carl usually does as she says. He then retreats into the small shed he resides in, locking the door behind him, allowing Carl to brood amongst all his rather impressive collection of nudie magazines and cheesecake pictures tacked up on a wall in solitude.

Shortly after, when Alan heads to town for some supplies, Carol is once again left all alone at the house when Duke returns. But this is not the same friendly dog. Nope, this is a snarling and savage beast (-- you can tell by its constantly wagging tail), who pursues Carol around the house and proves too fast when she tries to shoot him.

Soon out of bullets, Carol retreats outside and pounds on the shed door; but Carl refuses to let her in. (Most likely in retaliation for banning him from the main house a few scenes earlier.) And when Duke charges in for the kill, a desperate Carol grabs for Carl’s discarded ax and prepares to defend herself…

Back in 1954, the newly minted American Releasing Corporation was one of the bidders looking to distribute Roger Corman’s first film, Monster From the Ocean Floor (1954); a film Corman claimed he slapped and dashed together for a mere $12,000. (Other reports put it around $25,000).

But James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff, the co-founders of ARC, eventually lost out to Robert L. Lippert, who made a killing on the film. Hard not to when everything over that minute budget was profit.

“We went with Lippert because he was the only one we met who offered me an advance -- about $60,000 -- against his distribution income,” said Corman in his autobiography, How I made 100 Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (1990).

“It was Lippert who decided to change the title. He felt It Stalked the Ocean Floor was a bit too literary. The change may have helped. The picture earned enough at the box office to more than double [that initial] advance. This enabled me to cover my costs for The Monster from the Ocean Floor, immediately pay back the money I had borrowed [to make it] -- the deferments for the lab costs, prints, and the composer, and I had enough profit to go right into production on my next picture.”

Roger Corman.

Thus, Corman would take $50,000 of that payout and financed The Fast and the Furious (1954) for his Palo Alto Productions. And while several studios showed an interest in this fugitive road race thriller, Corman had been around long enough to know it would take forever to see any financial turnaround on his end.

Said Corman, “Right away, I saw the trap in low-budget production. You put your money up, make your film, release it, and then possibly wait a year for your money to come back, if it ever does. You’re out of business for a year unless you have another source of income.” Which he didn’t.

“It took about six weeks to get an answer print for The Fast and the Furious,” said Corman. “I got offers from Republic, Columbia and Allied Artists to distribute the film with guarantees to get back my costs and possibly earn a profit (eventually). But I wanted to use this picture to set up a multi-picture deal.”

Thus, wanting the money upfront again like with Lippert, Corman gave Nicholson and Arkoff thirty days to come up with a better offer. Said Corman, “I had several meetings with Jim and Sam. I told them I’d finance my own films but wanted to get back my negative costs -- what it costs to make the movies -- as soon as I finished each one.”

Essentially, Corman was asking them to pay off The Fast and the Furious on delivery so he could take the timely financial reimbursement and start rolling on his next feature right away. And not just a one time deal either, but the same deal on a whole series of films, which would help ARC find their feet as a studio and distributor and keep Corman consistently employed doing what he wanted to do: make more movies. A win-win situation for both parties.

“We started at a time when everybody said it was crazy to start a picture company,” Arkoff told Tom Weaver (B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers, 2006). “The only independents in those days were the one-lung producers who used to go to Griffith Park or one of the movie ranches, and for twenty-five or thirty thousand bucks each make two westerns, back to back, with the same cast, the same horses and virtually the same story. Maybe they’d change the villain or something, and sometimes they didn’t change a damned thing.”

Samuel Z. Arkoff (left), James H. Nicholson (right).

Also of note: “We are not interested in winning Academy awards,” Nicholson told the press back in ‘55, according to Mark Thomas McGee (Fast and Furious: the Story of American International Pictures, 1984). “We are interested only in pictures which the exhibitor can play with the assurance that he will make a profit.” Also according to McGee, Nicholson would boldly announce that ARC would be “releasing eight features in 1955, four in color and one more in Vistarama” -- an anamorphic process that may or may not have really existed. What also didn’t exist were those seven other films -- or the money to make them.

Even if they could afford to make them, which they couldn’t, they would also need someone and somewhere to exhibit them. And so, to kill two birds with one stone, after borrowing some money for a cross-country bus tour, Nicholson (and sometimes Corman) barnstormed The Fast and the Furious through several cities, looking for sub-distributors and regional exhibitors who would, hopefully, book the film. ARC would then take these advances and use them to finance their proposed picture slate.

Joseph E. Levine.

At the time, with the major studios cutting back on production, these theater owners and exchanges were starving for product (-- see our review of Beginning of the End (1957) for a deep dive to get the whole scope of that era), which helped them sign up 25 investors in total, including their biggest catch -- Joseph E. Levine, out of Boston.

However, according to Corman (Corman, 1990), there was a quality clause built into the deal. “The films had to at least reflect the production value comparable to Monster from the Ocean Floor or Fast and the Furious” -- something that would prove extremely relevant for our tale today.

Thus, with tentative finances set, a deal was struck with Corman: ARC would distribute The Fast and the Furious through their new network along with Corman’s next two films, guaranteed, which would be financed by the advances from these distributors, sub-distributors and exchanges.

“We had a three picture deal with Roger,” said Arkoff (Weaver, 2006), one of them being The Fast and the Furious, which was already completed. “And he had a certain amount of money as a budget [to complete the other two].” One was slated to be a Western, the other Science Fiction in nature, made specifically with the untapped youth market in mind. And so, with the princely sum of around $120,000 in front money, Corman set to work.

First up was the Western, Five Guns West (1955) -- sort of a proto, paired down version of The Dirty Dozen (1967), where five criminals are recruited by the Confederacy for a dangerous mission in exchange for a pardon. Here, Corman faced a dilemma. Both the Western and the follow up Sci-Fi Creature Feature were supposed to be shot in color, which would escalate production costs considerably. And so, the producer made a fateful decision and hired himself to direct the Western for no pay in order to save some money.

After all, How hard could that be?

“The truth is I was extremely nervous when I went out to shoot my first picture (for ARC),” said Corman (1990). “I had planned everything. Then I awoke on the first day of shooting and drove to the location through an incredible torrent of rain. This wasn’t possible. My first day! I hadn’t even started and I was already behind schedule. I got so worked up and tense that I pulled off the road and threw up.”

Thus, Corman would spend most of the rain-plagued shoot throwing up as he battled his nerves and struggled to get the film finished on time. And by some miracle, he did.

Said Corman, “Five Guns West was a breakthrough for me. With almost no training or preparation whatsoever, I was literally learning how to direct motion pictures on the job. It took me four or five of these 'training films' to learn what a film school student knows when he graduates. But while the mistakes they make in student films are usually lost forever, mine were immortalized.”

However, while he did successfully complete that film on time, he also went way, way, way over budget, leaving him with just $30,000 left to deliver a second finished film or he would default on his distribution deal. (Other reports put this amount as low as $23,000.) And worse yet, according to his contract, if Corman went over budget, he would have to make up those shortages out of his own pocket. Money he didn’t really have.

Luckily, Corman had gotten wind of a screenplay written by Tom Filer called The Unseen. Filer would go on to write The Space Children (1958), an underappreciated "Science Shocker" for the storied two-punch combo of William Alland and Jack Arnold after they left Universal for Paramount. In the pages of The Unseen, a malevolent, non corporeal alien intelligence attempted to conquer the world unseen by controlling animals and weak-minded humans.

This all sounded perfect to Corman, especially the ‘non corporeal’ part, meaning the alien threat would be an invisible threat and save him hundreds if not thousands in production costs. And to save even more money, the film would be shot in both black and white and non-union. But that also meant that Corman, now a member of both the Producer and Director's guild (PGA, DGA), could neither produce or direct the film -- at least not “officially."

Albert S. Ruddy.

Here, Corman would raid the local universities and film schools to fill out his amateur crew, finding diamonds in the rough already, who would go onto have huge impacts on the industry, including future Academy Award winner Albert S. Ruddy, who would go on to produce films like The Godfather (1972), The Longest Yard (1974) and The Cannonball Run (1981).

“I worked on one of Roger’s first films,” Ruddy confessed to Chris Nashawaty (Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen and Candy Stripe Nurses, 2013). “I was going to college at USC, and this girl I was going out with got a job on a Roger Corman movie. They were shooting it in the desert past Palm Springs. I loathed the idea of this girl going away all summer without me, so I called the director and asked if I could get on the movie.” He sure could

Said Ruddy, “I did everything from production design to special effects.” Ruddy would also serve as the film’s head chicken wrangler. “There’s a scene where this woman is feeding the chickens corn, and I’m behind the camera, with a cage full of chickens, and I had to start throwing the goddamn chickens right in her face as she’s screaming!”

Ruddy would officially be credited as the Art Director on the finished film. Meanwhile, Corman promoted David Kramarsky, his assistant and production manager on Five Guns West, to be the producer on The Unseen; and for his straw-man director, Corman also promoted Lou Place, who had served as his assistant director on the previous Western.

“The film was very sparse on the money because [Corman] had actually spent more than he wanted to on Five Guns West,” Arkoff told J. Philip di Franco (The Movies of Roger Corman, 1979). “So Roger went non-union, and hot on his trail were those watchdogs from the Screen Actors Guild and IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees). They would run into Roger and he would dart off the other way into the desert. It was a kind of continual chase.”

And so, with Corman ghost-directing from the sidelines, and Everett Baker, a film scholar and teacher at UCLA, handling the cinematography, location shooting around Palm Springs, Indio, and the Coachella Valley was almost completed when those unions finally caught up to him and threatened to shut it all down unless everyone joined up and got paid union wages.

After ordering Kramarsky to hideout until the heat died down, after mulling over his options, with the completion deadline and a possible default looming, a panicked Corman ultimately went with Plan B: he dismissed the entire crew and finished off the film himself over the course of two days, hiding out and shooting at Lou Place’s small sound-stage located on La Cienega Boulevard near Culver City, with only Floyd Crosby behind the camera.(This decision would also probably explain many of the film's infernal leaps in plot logic.)

Crosby was an interesting guy, who won a Golden Globe lensing High Noon (1952). And while never officially on the Blacklist, Crosby found himself on the “unofficial” Greylist, which found him equally shunned by the majors. But, he landed on his feet well enough with Corman and would go on to a long career shooting for him and on other films for the minor majors.

Floyd Crosby (left), Gary Cooper (right) on the set of High Noon.

“I worked on one of Roger’s first pictures, Monster from the Ocean Floor” said Crosby (Franco, 1979). “It was the only picture I ever saw made without any direction at all.” In Corman’s defense, he only produced that film. It was directed by Wyatt Ordung, but that’s a whole ‘nother story for another day.

Funnily enough, though, while watching the film, it’s the location footage of Baker that really elevates the otherwise moribund material of The Unseen. Add in those groves of date trees, which makes the surroundings look like some alien hellscape, and, well, it’s all very eerie and effective -- and the whole film appears to be dying of thirst.

"Hiya! No. Don't worry about me. I'm irrelevant to the plot."

There’s also some pretty effective sound-design during the animal attacks, too, as the film relied heavily on what you hear and not what you see. That’s right. In this film, not only do we not get to watch the paint dry, we get to listen to someone else describe the paint drying for us. And sometimes we even get to hear someone describe how someone else described how the paint dried. Good times.

And with no money, the film was mostly shot without sound, but it was scored fairly effectively with a bunch of stock library cues and public domain music to set an otherwise non-existent mood, overcompensating for the dialogue never quite syncing up. The musical score was credited to a non-existent John Bickford, and included pieces by Richard Wagner, Dimitri Shostakovich, Giuseppe Verdi, and Sergei Prokofiev.

Thus, with no alien to speak of and no action either, it’s left to the actors to keep everyone awake. And while I kinda dug the family drama that centers around Carol, with whom I genuinely sympathize and empathize with, there isn’t a whole lot else there -- and so, we latch onto whatever we can.

What little we do see of Carol’s meager existence was bad enough. Alan is never around, either out failing as a farmer or always running into town without her; and now Sandy is about to leave her behind, too? Is it any wonder why Carol is lashing out at everyone around her?

But then, surprise, surprise, the script actually gives her an arc and

eventual redemption in the middle of all those cut-rate animal attacks. I'm just as shocked as you all are, my Fellow Programs.

Kudos to Lorna Thayer for elevating Carol Kelley well above the ‘as written’ rote bitch caricature threshold. Everyone else is fine, I guess, and serviceable enough for this hackneyed plot. But only Leonard Tarver’s performance as the silent and menacing Carl gets even close to what Thayer brought to the table, as she’s isolated even further from her family after Carol winds up having to kill Duke to save herself.

Of course, Sandy doesn’t believe her story about the dog going rabid, which only drives the wedge between them even deeper. Later, as Sandy wanders in a daze grieving, she suddenly snaps out of her stupor in the middle of the desert with no idea how she got there. Stranger still, a mesmerized Carl seems to be on the same course until she gently takes him by the hand and leads him back to the farm.

When they get back, Carol also seems to have “woken up” a bit and snapped out of her morbid funk. And as the family reconciles, Sandy relates her strange trip into the desert, claiming to have been drawn out there by a strange humming sound.

Then, things kinda escalate the following morning -- but remember, that’s a relative term when dealing with a somnolent flick like this, when neighbor Ben is trampled to death by Sarah the cow.

Meanwhile, back at the Kelley homestead, Carol is assaulted by their clutch of chickens when she tries to gather up some eggs.

Now, you would think Alan would be the one to put the pattern together since he was the one who was similarly attacked by some fine feathered fiends; but, nope, Carol is the one who theorizes all the animals are revolting against them en masse just so the patriarchal and patronizing Alan can say she’s only imagining things. (And why hasn’t she left this guy yet?)

Elsewhere, Carl is finishing his chores until he hears that humming sound again, and then follows a dove off into the desert. As you do.

Now, I’m sure I failed to mention that Sandy’s 18th birthday was fast approaching, too, which explains why she and her mom are currently in the kitchen trying to bake a cake. (One of the film’s running themes is using Carol’s culinary failures to represent her failure as a woman, a wife, and a mother. But now that she’s reconciled, we finally have success. Oy.)

Then, Sarah the cow wanders into their yard just as Alan discovers Ben’s trampled body several miles away. Alas, a curious Sandy goes out to investigate and nearly gets trampled to death!

And when her mother moves to save her, she almost gets trampled to death, too. But then, a shot rings out and Sarah falls dead. (Hamburgers for supper, yay!)

Seems Alan, thinking there may be something to this all-out animal revolt after all, beat feet back to the farm. And when he tries to phone the Sheriff, several birds attack and knock out both the phone lines mid-call and the electricity by smashing into a transformer until it explodes.

Then, all attempts to leave by car are thwarted by more swarming birds, which culminates in a full blown assault on the farmhouse by this avian hit-squad. And worse yet, they seem to be under the direct control of that same hidden intelligence.

Now, the funniest part about this scene was the innovative way Corman used to show the ferocity and severity of this attack in the cheapest way possible: with the copious amount of bird-shit accumulated on the Kelley's sedan. (See photos above.)

Meanwhile, Carl has finally reached the crater Duke the dog found earlier. And as the hum gets louder, Carl tries to cover his ears but then a light flashes from the metal object and he collapses to the ground.

Meanwhile, meanwhile, Deputy Brewster manages to trace that interrupted call to the Kelleys and was on his way to investigate when he comes across Carl wandering along the road. Offered a lift, Carl gets in back but then clobbers Brewster, running the car off the road. He then resumes the alien's bidding and wanders off.

Back at the house, the attack apparently over, the shell-shocked but still standing Kelleys are going ahead with Sandy’s birthday party because of course they are. But when the invited Larry Brewster fails to show, her parents console a distraught Sandy but the party is officially ruined. Later, fearing something has happened to her boyfriend, Sandy sneaks out of the house to go and look for him.

Meanwhile, meanwhile, meanwhile, Larry, who’s recovered from that cold-conking, is now out in the desert looking for Carl, who in turn is being drawn once more to the crater. (Isn’t this fun?) Larry catches up to Carl at the crater, where they struggle until the deputy kills Carl -- I think. Because after he clears off, Carl recovers and ambles off into the desert once more. Again, not really sure if he's just wounded or has been reanimated by the alien to do its bidding. Interesting idea, but, meh, it really doesn't matter as far as the movie is concerned.

Then, when Larry makes it back to the Kelley homestead, they all discover Sandy is now missing. And so, after somehow deducing strength in numbers reduces the malignant whatever’s power and influence, Alan and Carol join Larry to go and search the desert for Sandy. And then Alan, Carol, and Larry, and Sandy, and the Zombie Carl, wander around for a bit; and then they wander some more; and then they wander even more than that until another reel is expired.

Unfortunately, Carl winds up finding Sandy first, snatches the girl up, and then carries her back to the crater. No. Wait. He’s heading back toward the house. No. Wait. Now he’s heading for the crater. (Sensing a pattern here.)

Anyhoo, eventually, they all wind up at the crater and the grand puppet master behind all these shenanigans finally reveals itself and emerges from what turns out to be a spaceship embedded in the bottom of the impact crater.

But just like with everything else in this damnable movie, this big reveal is completely underwhelming and totally botched in the execution.

"Wait. That's it?!"

Now, for those not in the know, American Releasing Corporation would morph into American International Pictures by 1956 after the company had found its legs with a proven formula on what would sell and what wouldn’t.

As the legend of this proven formula goes, the folks at ARC / AIP would come up with an outlandish title first; then design a poster and promotional campaign for that title second; then thirdly, float that title and promotional materials past their exhibitors; and then finally, whatever got the most nibbles would get a script commissioned to match it; and then, and only then, would the film get made.

The Los Angeles Times (September 21, 1958).

“We do our planning backwards,” Nicholson admitted to Philp Scheuer (The Los Angeles Times, September 21, 1958). “We get what sounds like a title that will arouse interest, then a monster or gimmick, then figure out what our advertising is going to consist of. Then we bring in a writer to provide a script to fit the title and concept … These titles are simple and don’t leave any doubt what the picture is about.”

Added Arkoff, “Titles, monsters and gimmicks are the stars. If these can’t attract (an audience), we have missed the merchandising boat.”

This, of course, did not happen with The Unseen. For it wasn’t until the film was in production before Nicholson cooked-up a new and more exploitable title, The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), which was based on the script’s notion that one mind-controlling alien could see through all the eyes of the animals and humans it possessed. "To make the optical prowess of the alien appear literal, Nicholson conceived the Beast title and had designed a poster entity that saw every which way," noted D. Earl Worth (Sleaze Creatures, 1995). "What the artist wrought conveyed no suggestion of anything except primal malevolence, nor was there any hint the beast was extraterrestrial."

“The Beast with a Million Eyes was one of Jim’s million-dollar titles that he brought into the office one morning,” said Arkoff in his autobiography, Flying through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants (1992). And from there sprung a delightful promotional and advertising campaign for the film, complete with an advance poster courtesy of Al Kallis, claiming the film would be shot in WideScreen and something called Terror-Scope (-- both extreme fallacies).

Now, Kallis’ art seemed to forgo the esoteric notion of the alien being just an ethereal force of evil that possessed its way to intergalactic conquest, and instead, showed a multi-optical demonic cat-fish, with ferocious fangs, flaring nostrils, and tentacles, menacing some girl in a bikini (-- later changed to her unmentionables and a flimsy negligee).

When they sent this campaign out to their distributors, most were ready to buy it sight unseen. (Yes. I saw what I did there.) In fact, Joseph E. Levine was so enticed by these promotional materials he promised to bring another bigwig to the distributor’s screening, who he promised could get the film shown all over New England -- and maybe even New York City.

Thus, things were looking pretty good for the upstart ARC -- at least it was until they got a work print of The Unseen from the lab, took a look, and saw nothing that resembled a monster -- at all.

Nope. Just a lot of talking, ambling through the desert in a slow circle, and a miniature “spaceship” that consisted of what looked like several kit-bashed together items scrounged from the desert, including what appeared to be a coffeepot or a teakettle for the main body, with a few spent shell casings glued onto the side, which was then mounted on some tin cans, with a sad little whirligig contraption stuck on top of it, wobbling away, which is EXACTLY what it probably was.

“The closest thing the film offered in the way of a special effect was a spaceship, which was actually a round tank, half-buried in the sand, with a propeller spinning around its top,” noted McGee (1984). “One reviewer would later describe it as ‘an over-sexed tea kettle.’ Arkoff was later quoted as saying that it was a teakettle.”

“When the editor delivered a work print to us, it didn’t even have a beast in it, much less one with a million eyes,” said Arkoff (1993). “Even with a great title, a picture still has to deliver on what’s promised, and Corman had neglected to put a beast in the film. He just didn’t have the money for it. So Jim and I had to scramble to turn an $8 teakettle into the monster with a million eyes. That was what filmmaking was like in the 1950s.”

Over the decades since its production, Arkoff’s recollections appear to have gotten a little fuzzy on the details, as he would often mistake the mock-up of the spaceship for the titular beast itself, saying things like, “We poked forty holes in it -- not a million, but who was really counting? -- and as the camera rolled, we ran steam from the vaporizer through it. The mist was designed to give the beast an ominous appearance; but more importantly, it obscured the kettle just enough so viewers couldn’t get too clear a look at it.”

Now, what happened next is truly the stuff of cinematic legend. It has been told many times over the years, been embellished, rewritten, and been contradicted many times from several different sources. However, after really digging into this baffling chain of events, which eventually saved American Releasing from an early extinction, I think what happened next went a little something like this:

Forrest J. Ackerman.

After the first in-house screening of the rough cut, and one hurried phone call to Corman later, their new partner finally admitted to running out of money and how he did the best he could under the circumstances. Full well knowing the whole shebang was riding on the success of these first few features, Nicholson gave Corman Forrest J. Ackerman’s phone number and told him to find them a monster as soon as possible.

According to McGee, Nicholson and Ackerman were acquaintances since belonging to the same Science Fiction Club when they were teenagers. However, that fix would take some time. And with that exhibitor screening looming, a desperate Arkoff called Levine and suggested he and his friend skip the screening altogether but Levine could not be swayed.

Famous Monsters of Filmland (No. 18, 1962).

“When we finally screened the picture, it was a disaster,” said Arkoff (1992). “As the projector rolled, Jim and I kept slumping lower in our seats,” which were located in the Pathe Labs' screening room.

But then, as this improbable legend continues, while the film was still playing, in an act of pure desperation, Nicholson abandoned his seat and headed to the projection booth, where he absconded with the last reel. He then took this to one of the editing suites, spooled it out, and then attacked the actual negative itself with his car keys (-- other sources claim it was a pair of scissors), scratching holes into the emulsion, trying to give the steaming pile of garbage cratered in the desert multiple eyes, which might help explain Arkoff’s later recollections, adding credence to this whole tale.

(Artist interpretation.)

Nicholson then added a few more scratches to emulate some kind of death ray. He then took ink from his pen and smeared it all over the negative. And when they spooled it up, it was a mess but it kinda looked like the junk was firing off … something.

And so, it was this tampered-with version of the climax that they wound up showing to the distributors in what would turn out to be a failed Hail Mary. Even before it was over, Levine was chasing the other disgusted distributor up the aisle and out of the theater. And those that remained behind weren’t so happy either, ready to engage that “quality clause,” but were swayed with a promise that an actual monster was forthcoming.

Levine, meanwhile, was a little more philosophical and practical over this disaster as he either whipped out his checkbook on the spot or called Arkoff later and offered to buy the title and promotional materials for $100,000 flat (-- other sources say $200,000), with plans to burn what he had just witnessed and start over from scratch. Said Arkoff (1992), “Even the toughest movie critic had never suggested torching one of our movies.”

Levine, of course, would soon go on to form his own production company, Embassy Pictures, and found great success with his own outlandish titles and ad campaigns when he imported films like Godzilla: King of the Monsters (alias Gojira, 1956) and Hercules (alias Le Fatiche di Ercole, 1959).

But Nicholson and Arkoff turned this generous offer down, perhaps foolishly at the time, hoping the man who got them into this mess in the first place could also get them out of the same jam.

Meanwhile, Corman was still scrambling to shore things up on his end. I’d be curious to know if he ever considered bringing back Bob Baker, who had provided the killer mutant amoeba for The Monster from the Ocean Floor, which menaced the heroine and got a mini-sub rammed into its single eyeball. (Always had a soft spot for that delightfully ungainly thing, which is rumored to have begun life as a female contraceptive.)

Baker was a puppeteer and marionette operator, whose work would later be seen in The Angry Red Planet (1959) -- I’m thinking he pitched in on the Rat-Bat-Spider, Escape to Witch Mountain (1975), and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). But Corman would eventually sub in one puppeteer for another.

He called Ackerman as instructed, who first suggested his friend, Ray Harryhausen, who had just wowed audiences with his stop-motion monsters in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955).

But Corman knew he would prove way too expensive, and so, Ackerman next suggested Jacques Fresco, who had recently pulled-off the special effects for Project Moonbase (1953). Now, the allotted budget for this upgrade was a mere $200. Fresco asked for $1000. Next.

Salvation would eventually come in the form of Paul Blaisdell. Sort of. See. As his agent, Ackerman had recently signed on Blaisdell as a client to help sell his fantasy illustrations to the Pulps and Sci-Fi magazines.

Art by Paul Blaisdell.

“Ackerman knew very well that Blaisdell had no experience as a monster maker,” noted Randy Palmer in Paul Blaisdell: Monster Maker (1997), his exhaustive biography on the soon to be legendary creature creator. “But he recalled that Blaisdell had mentioned building his own model airplanes from scratch and working with soap carvings and homemade puppets when he was growing up. He gave Paul a call and explained what Corman wanted."

Blaisdell had hinted about wanting a crack at doing some special effects work. And here, employing what was to become his usual modus operandi, he requested to read the script first to see what exactly would be required of him before committing.

Paul and Jackie Blaisdell.

Said Palmer, “Corman assured that the only thing the picture required at this point was a miniature monster to come on screen for a few seconds, point a ray gun at its (offscreen) human adversaries, and then topple over gracefully when it died. That was all there was to it.”

With these assurances, and after reading the script with his wife and frequent collaborator, Jackie, Blaisdell agreed to take on the task when a desperate Corman agreed to double his salary from $200 to $400 to cover both parts and labor. And since any kind of stop-motion was out of the question, Blaisdell decided to keep it simple and just make his beast a scaled puppet.

From there, “Corman allowed Blaisdell free reign when it came to dreaming up the look of the creature … and Blaisdell let his imagination run free,” said Palmer. “The basic design incorporated humanoid as well as reptilian and mammalian features -- an interesting combination that would recur frequently in some of the artist's later work. He experimented with different approaches to the design of his extraterrestrial interloper, eventually settling for a humanoid outline with an oversized, exposed brain that would represent the creature’s advanced intellect.”

According to the script, the Beast would emerge from the ship out of an airlock; and figuring this would make it partially obscured, with the creature only being seen from the waist up, it was built accordingly with no legs to save even more time and money.

Rare color photo of "Little Hercules."

The 18-inch puppet, dubbed Little Hercules, was made of latex pulled from a mold of modeling clay sculpted by Blaisdell, which was then meticulously painted to bring out the details. Its vicious teeth originated as a pair of plastic novelty vampire fangs, and its antennae were a pair of lizard tails snipped from a couple of off the shelf rubber toys.

A hose was attached to the inside of its nose, allowing the puppeteer to blow cigarette smoke out of its nostrils to add some menace. Its articulated wings were wire coat hangers covered in latex. And the beast's gnarled hands were sculpted and realized by Jackie, which could hold the miniature dime-store disintegrator as instructed.

“Once Blaisdell accepted the assignment the pressure was on to get things moving as quickly as possible,” noted Palmer. “Working under the gun was something that Blaisdell would become very much accustomed to as the 1950s progressed and Roger Corman and other budget film producers began turning to him not only for their movie monster, but for props, scenery, and special stunt effects as well.”

Thus, Blaisdell was also tasked to help improve the antagonist’s mode of transportation, which was also getting an upgrade over that errant tea kettle. And to those ends, Blaisdell would build the miniature version of the alien rocket, which he had to do not once, but twice, as a lack of communication wound up resulting in two completely different versions of the same ship.

Blaisdell's original design for the alien ship (courtesy of Bob Burns).

According to Blaisdell (by way of Palmer), the new full-size ship was “a hodge-podge of materials pieced together from a junkyard in Indio, California: an airplane fuselage and nose, some Model-T Ford mufflers, garbage cans, and a bunch of iron rods and plastic tea cups.” And to my eye, it looks like it was built to try and match that damnable tea kettle in what I will assume was an admirable but ultimately futile attempt at continuity.

And so, Blaisdell scrapped his delicate egg-shape design and started over from scratch to match the new industrial mock-up. He would also build a miniature desertscape on Place’s soundstage and helped provide the pyrotechnics for its launch. This would also have to be staged twice as on the first try the rocket launched prematurely when Place’s assistant, John Milani, clumsily tripped over some wires. The errant model landed in the rafters, where it sat until the following morning when they retrieved it, tried again, and finally got the shot.

Blaisdell would also build the ship’s outer facade and the airlock with a sliding hatch for Little Herc’s closeup, which was made out of corrugated cardboard painted silver. In theory, one person would open the door, Blaisdell would animate the puppet, and Jackie would handle the strobe-lighting to give the interior some other-worldly flare.

Alas, all of this attention to detail was about to go all for naught, according to Palmer, saying, “Because Roger Corman wanted to get Beast with a Million Eyes in the can as quickly as possible, none of Little Hercules’s inbuilt talents were utilized on camera.”

Little Herc and Jackie Blaisdell.

Blaisdell would later recall that “the crew was pretty impressed with the Beast -- so much so that everyone wanted to be on hand during the shooting. And by the time the cameras were ready to roll, he was surrounded by so many people he barely had room to turn around.”

Said Palmer, “Although the flexibility of the model could at least allow for varied arm movements, the director was in too much of a hurry to let him experiment with obtaining the best possible effects. The end result was a flatly lit, unimaginatively staged shot of the opening airlock and a quick cut to the Beast positioning his ray gun, along with one or two close-ups of the monster’s snarling face before it inexplicably falls over dead.”

“When the film was shot everybody was climbing all over the mock-up of the spaceship and trying to light the Beast, and everybody wanted to get in on the act. And that’s just what they did, until the Beast was so choked up he could hardly move,” recalled Blaisdell (Palmer, 1997).

"Unfortunately, that shows on the film, along with the wrong camera angle -- after all, Paul Birch was supposed to be looking up at the spaceship, not at it. Those (insert) scenes were all shot within the space of about ten minutes, and unfortunately, it shows.”

Here, it should be noted that the shot angle was the least of the production's worries when it came to matching footage as the climax played out, because it isn't hard to notice how far off the scale is between Carl and the ship as he enters the impact crater with Sandy.

Then, the rest of the gang finally shows up. And after taking in this improbable scene, Alan doesn't shoot but manages to reach the hypno-whammied Carl, who listens, then fights off the malignant alien influence long enough to let Sandy go before expiring -- and for good this time, too.

I'm sure in the script it was supposed to be huge, but given the angles, Alan is as tall as the ship, if not taller, and would've been looking directly

into the eye of the slave beast as it exited the porthole. Ergo, Blaisdell had also unwittingly built Little Herc not

to scale but at its actual size! There's no other way he would've fit

into that tiny ship.

And to add insult to injury, Corman wasn’t finished doctoring the scene just yet.

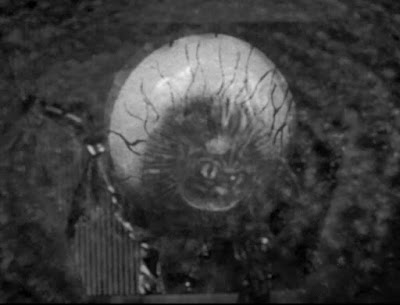

“Blaisdell’s attention to detail was mostly lost on audiences who saw the finished feature in 1955 or caught it on television years later,” said Palmer. “Paul was horrified to discover that not only had the cameraman filmed the Beast at a totally inappropriate angle but a ghostly floating eyeball and hypnotic spiral (more of a ripple dissolve of some kind) had been superimposed over the scene, which made it look even worse. The scene played so quickly and was shot so poorly that the Beast’s devil-bat-wings, the chains and manacles, and even the ray gun could barely be discerned at all.”

Added Blaisdell (Palmer, 1997), “Why they superimposed that awful eyeball over Little Herc is something I’ll never understand because it just made the whole scene look ludicrous. The Beast is supposed to be controlling the slave from inside, like a kind of parasite, not floating above him like a disembodied orb. Of course, how the real Beast was able to pilot the ship away after Paul Birch shot it with a Winchester rifle is something even I can’t explain.”

Now, here, it should also be noted that in the finished film, Birch's character never actually gets around to shooting at the alien either. Nope. Instead, he and his wife deduce that the power of familial love and positive thinking can thwart the invader's mind-controlling efforts.

And as the family rallies together, this psychic backlash sends the slave beast reeling as it rather comically keels over dead, and then the pilot-less ship blasts off back into space, bringing an already highly ignominious film to an even more ignominious end.

As Palmer noted, Blaisdell would continue working for Corman and would fair better as he became AIP’s defacto in-house FX expert. Working alongside Jackie and his best friend, noted gorilla man Bob Burns, he would provide Marty the Mutant for The Day the World Ended (1955); Beulah, the inverted Venusian Turnip, for It Conquered the World (1956); Cuddles, probably his most famous creation, for The She-Creature (1956), which was then recycled for Voodoo Woman (1957), and then given a double-mastectomy for Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow (1959); and the delightful cabbage-headed aliens for Invasion of the Saucer-Men (1957). Memorable monsters all.

He would also provide miniaturized props (and one giant syringe) for The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), desiccated corpses for The Spider (alias Earth vs the Spider (1958), and the oversized dress settings for Attack of the Puppet People (1958).

(L-R) Lori Nelson, Blaisdell, Corman, The Day the World Ended.

As for the fate of Little Hercules, when Blaisdell retired, he donated the puppet to Ackerman, where it joined his legendary collection of props and movie memorabilia. Alas, it was put on permanent display in a sun-drenched room at the fabled Ackermansion, where it slowly cooked until the latex started to rot away. It was then moved to a refrigerator but the damage was done and it irrevocably fell apart.

Now, turns out the origin of that “disembodied orb” that obscured Blaisdell’s initial handiwork can be traced back to Albert Ruddy, who later recalled (Nashawaty, 2013), “I got one of those extended aluminum pieces with a mop at the end, then I got a red rubber (suction) syringe that you squeeze into your ear, and painted it all a slimy green. And then I painted on an eyeball with veins.”

As for why they decided to add it to the finished feature? Aside from blind panic, well, that’s a cinematic mystery that I fear may never be resolved. Believe me. I tried.

The only real clue comes from McGee, who reported "Kramarsky was shocked when he saw the effects sequences. The miniatures had looked fine at the studio. On film they looked terrible. He asked the lab to print the scenes darker but they didn't." (McGee, 1983). Which makes one wonder if it was Kramarsky and not Corman who shot the inserts. That's me shrugging right now.Of course, technically speaking, using only one superimposed eyeball still left the film 999,999 eyes short -- 999,997 if you count Little Herc’s reptilian peepers. But Blaisdell would have an explanation for that, too, saying it would be impossible to show something that was just a “molecular force.”

“[What] appeared in the film was the slave of the Beast with a Million Eyes, who had no material concept in reality,” explained Blaisdell in the pages of Fangoria Magazine (Issue No. 8, October, 1980). “The title comes from the supposed fact that this was a creature that was a malevolent entity, possibly made up of a molecular cohesion, that can look through the eyes of all the creatures of whatever planet it lands on; but it had no physical being. It used a creature from another star system to pilot its ship, and this creature is what you see in the film.”

Upon completion, these newer sequences were then spliced into the old; and not taking any chances, they cobbled together that opening montage to explain the lack of the creature promised on the poster, essentially negating all suspense to come, leaving the characters to play catch up while the informed audience quickly loses patience with the lot of them.

When it was put in front of a preview audience, the comment cards were so scathing an embarrassed Place asked to have his name removed from the credits before its general release. And since Corman wasn’t about to take credit for any part of this total cluster, he gave the dubious honor of producer and director for Beast to Kramansky.

Now, ever since its completion, there was a period where Corman would treat Beast With a Million Eyes as the bastard step-child of his oeuvre and would do his best to essentially disown and distance himself from the film.

He barely mentions it at all in his autobiography, referencing it twice, and passively at that, claiming he only backed the feature; and it barely appears in other retrospectives, too. And when it does, he goes into total denial mode, like in Franco’s book, where he pointed an accusatory finger indirectly at Kramansky for the film’s myriad shortcomings.

The Philadelphia Inquirer (January 22, 1956).

As to whose fault it really was (it was Corman’s), it really didn’t matter in the end and everybody learned a lesson. For while it was still a giant hodgepodge of nonsense and lofty script ambitions that they could never hope to expand upon, topped with a leaden, pious ending, The Beast with a Million Eyes was eventually released into enough theaters to manage a profit -- thanks in most part to those incredible but >slightly< misleading posters and newspaper ads.

On its release, the film was often paired up with a few other strays looking for a second feature. And so, The Beast with a Million Eyes would be paired up with the likes of Ed Wood’s Bride of the Monster (1955) and Bert I. Gordon’s King Dinosaur (1955). It also appeared alongside The Sins of Pompeii (1950), Footsteps in the Fog (1955), and one particular brain-bending, one night only showing with The Night of the Hunter (1955) in Columbus, Nebraska (November 25, 1955). And it would stay in circulation well into 1959, filling out other double-bills for AIP, serve the role of a “midnight chaser” at your local Drive-In, or show-up as the key feature for many a Midnight Spookshow.

The Salem News (December 27, 1957).

While I dug around I couldn’t really find much when it came to any concurring reviews of the film, with only a few blurbs that appear to come straight out of the pressbook; like this one found in The Valley Morning Star (January 1, 1956), calling it “a nightmare of an adventure when you meet the beast. If your heart is weak this is not the program for you, but if you like chilling, spine-tingling adventure then this is it.”

As for the more contemporary reviews, Scott Ashlin (1000 Misspent Hours and Counting) took the film to task for its monumental shortcomings, starting with the Beast itself. “There’s one thing the alien didn’t figure on. Just as hate opens the mind to invasion, so love closes it off; and because the aliens themselves know nothing of love, they are completely unprepared to deal with this eventuality. And not only that, the very presence of the alien, and its attacks on the Kelleys have had the effect of rekindling their long-lost love for each other. Ooff! Did you feel the filmmakers kicking you just there? That’s right -- this is going to be another one of those ‘talking the monster to death’ endings that we all love so much,” observed Ashlin.

Thus, “It is scarcely a shock to see that The Beast with a Million Eyes is one of the tackiest, trashiest monster movies ever to be made in Hollywood by somebody other than Ed Wood Jr. But unfortunately, it somehow fails to be tacky or trashy enough to be fun,” Ashlin concluded.

Others were slightly kinder. Said Nathaniel Thompson (Mondo Digital), “Though obviously very limited by its impoverished budget, this fascinating little film has enough rewards to make it stick in the memory, including some hallucinatory abstract methods used to indicate the alien's presence (like the) high-pitched screeching noise, and an animal attack premise that predates not only the '70s tidal wave of films but Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (1963) as well. The fact that it spends so much time on a dysfunctional nuclear family is also an interesting touch with the frustrated Carol a very far cry from the TV-friendly housewives so commonplace at the time; in fact, her early admission that she holds a grudge against her college-bound daughter is still pretty startling today.”

Portageville Southeast Missourian (August 18, 1955).

Meanwhile, “The Beast With a Million Eyes stands naked and embarrassed in its cheapness,” noted the impeccable Liz Kingsley (And You Call Yourself a Scientist!?). “Yet it cannot be denied that Tom Filer’s screenplay has … ambitions. Like so many science fiction films, and particularly science fiction films of the fifties, this film is a rumination on what it means to be human (specifically, a white American human). The nicest thing about this film is that it centers on a very ordinary family. Furthermore, the young lovers are here given short shrift; it is the middle-aged married couple upon whom the story focuses, two people who must defeat their adversary with no other weapon available to them but their own human natures; and to make this possible, and credible, the story first ventures into some surprisingly dark territory.”

But, as Kingsley continued, “The down-side of all this, however, is that in the absence of any scientific gizmos or military hardware, all that’s left is conversation. If you think TV shows like Star Trek pioneered the whole ‘out-debating the enemy’ trope, think again. The Beast With A Million Eyes serves up a painfully bad example of this kind of story resolution … But before this, I contend, it offers the viewer enough material of philosophical, if not quite dramatic, interest, that the film deserves to be treated with at least a modicum of respect.”

The Terre Haute Tribune (May 25, 1956).

And Phil Hardy stated in his quintessential book, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Films (1984), that this movie was not the affront to film in general as some would have you believe, but was “clearly intended as an allegory about a malevolent God.” And how “the film remains interesting, for all its flaws, if only for its unusual central idea.”

As for what I thought of the film, well, I think there’s just enough there to qualify Beast as an interesting misfire. I can appreciate how they almost made something out of nothing, but by the end everything had been stretched well beyond the original factory specs. And, well, as I said, you know your film’s in trouble when the opening credit sequence proves to be the most vivid and engaging part of your movie.

This animation sequence was provided by Bill Martin, who, along with Paul Julian, provided a lot of nifty stylized credits for Corman and AIP; the music was Shostakovich's "Symphony No. 10 in E Minor, an aggressive piece, making the credits one of the few engaging action scenes in the entire film, making one wish they could've put sprocket holes in them, too.

Perhaps Richard Harland Smith summed it up best for TCM, chalking it all up as a critical learning experience, saying, “If The Beast with a Million Eyes was far from his finest hour (and a quarter), Roger Corman continued to learn from his mistakes and to pioneer an independent filmmaking model that would be carried forward by the architects of the New Hollywood.” And to Corman’s credit, he would never make the same kind of mistakes again.

Nicholson, Arkoff and ARC / AIP would learn from this lesson, too, meaning to at least make a token attempt to have the action onscreen match what is shown in the promotional materials -- remind me to tell you all about the making of Flesh and the Spur (1957) sometime.

They would then ride that successful formula for nearly three decades of exploitation classics as Nicholson kept coming up with outlandish titles and slightly disingenuous, bait and switch marketing campaigns, while Arkoff kept juggling the finances to keep the company going for at least one more picture, and then Corman, with an assist from Blaisdell, would capture a “reasonable facsimile” of all of this on film. Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

And as a tribute to the formidable skills of these beloved hucksters, we kept falling for it over and over and over again. And we didn't seem to mind one bit.

Originally posted on October 7, 2017, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955) San Mateo Productions :: Palo Alto Productions :: American Releasing Corporation / EP: Roger Corman / P: David Kramarsky, Samuel Z. Arkoff / AP: Charles Hannawalt / D: David Kramarsky, Lou Place, Roger Corman / W: Tom Filer / C: Everett Baker, Floyd Crosby / E: Jack Killifer / M: John Bickford / S: Paul Birch, Lorna Thayer, Dona Cole, Dick Sargent, Leonard Tarver, Chester Conklin, Bruce Whitmore

%201955.jpg)

_11.jpg)

_13.JPG)

_6.jpg)

_5.jpg)

_10.jpg)

_ART-02.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

_14.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

_ART-01.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment