Our Tale of Southern, Deep-Fat-Fried Vengeance on a Stick begins at the Starlite Lounge, where Ron Lewis, owner and proprietor of said establishment, prepares to open for the evening crowd. And while his girlfriend, Susan Barret, who also serves as the Starlite's headlining act, warbles a tune from the stage, Lewis receives a phone call.

Seems there’s a big, clandestine poker game brewing a few States over. And according to the caller, there are some "pigeons" coming in from New York to gamble, meaning the pickings will be easy, and he wants to recruit Lewis to fly over and help with the plucking -- he'll even send his own private plane to fetch him.

Easy or not, a concerned Susan (Van Dyke) has heard this all before and doesn’t want him to go, saying she’s tired of him frittering away his money instead of doing something constructive with it, like paying off the club. But Lewis (Baker) claims he’s a gambler, and this is what gamblers do.

A few days later, when Lewis returns to the Starlite, his demeanor shows he must have lost -- and lost big time. But this turns out to be an elaborate joke on Susan because, in truth, he cleaned and plucked those Yankee pigeons completely; evidenced by the large satchel he’s carrying that's stuffed full of cash.

But that’s only half of it, says Lewis, as he’s also leveraged those winnings into stock on a new Las Vegas casino, where his new partners want him to relocate so he can run things. Yeah, life couldn't be going any better for our boy Lewis right now -- he typed ominously.

Too ominously, apparently, as this lucky streak officially ends later that night while Lewis drives home along lonely Talbot Road, where he comes upon two parked cars blocking the way: a Chevy and a Plymouth (-- details which will prove relevant).

When Lewis gets out to investigate, he gets shot at before the unknown assailant roars off in the Chevy. Here, Lewis also tries to hightail it out of there, too, but he can’t since one of those stray shots took out one of his tires.

One mounted spare later, Lewis makes it home without further incident. But he’s barely out of the car before a Sheriff’s Deputy named Haskins (Jenson) approaches, who then places Lewis under arrest without cause while demanding to know exactly what his detainee saw out on Talbot Road.

Assuming the position, an agitated Lewis wants to know what’s going on (-- and so do we), and his mood doesn't get any better when Haskins says he isn't going anywhere except straight to the morgue!

With that, realizing he's in some deep fecal matter, when Lewis starts resisting, a brutal struggle ensues. And as his garage is all but destroyed during the fight, both combatants are severely battered and bloodied until Lewis manages to kill his attacker by poking his thumbs through Haskin’s eyes before caving in his skull by bashing it repeatedly against the concrete floor.

With all the commotion, more cops and paramedics soon arrive on scene, thanks to the concerned neighbors, and Lewis is hauled off to the hospital. While policing the scene, after taking possession of Lewis’ gambling money, Sheriff Morello (Kimmerling) motions for Chief Deputy Bundy (Larch) to join him outside, where Morello claims that since this confiscated money is most likely a result of gambling, and since gambling is illegal in this State, technically, the money doesn’t really exist. Ergo, Morello deposits the satchel full of the non-existent money in his trunk while both men exchange evil smirks.

Later, when he wakes up in the hospital's detention ward, the battered Lewis finds a diligent Susan by his side. His lawyer, Andrew Ney (Bryant), is there, too, who woefully reports that things don't look too good for Lewis because no one can verify his story about the shootings on Talbot Road. But more damning is the Sheriff’s dispatch log, which alleges Haskins called in a reckless driver matching Lewis’s description before their lethal wrestling match commenced.

Knowing his client is good and cooked, Ney thinks they can possibly strike a deal with the District Attorney but Lewis refuses, swearing he was threatened and acted strictly in self-defense. Not trusting the cops, he tells Susan to hire some private detectives to do their own investigation. There has to be footprints and shell casings, he insists -- not to mention the bullet holes in his windshield and tire. But as they plot, little do they know, the room has been bugged and Morello is listening in on everything to permanently stay one step ahead of them.

Thus, when Susan returns home, she finds Morello’s goons waiting for her, who threaten to kill her if she tries to help Lewis in any way. Now, when I first encountered this film and wrote it up for the MotherShip some *gack* 20 years ago, it was culled from a TV-version seen on one of the SuperStations. (TNT, I think. Back when the SuperStations and basic cable, as a whole, didn’t suck.) Since then I’ve seen the theatrical cut and, well, I hope I don’t have to draw you a picture on how Morello’s goons punctuate their threat. Yuck.

Several days later, Lewis is still laid up in the hospital when Ney reports that he's turned up nothing new on his case. But Lewis still hopes the investigators Susan arranged had better luck. To which a confused Ney relays that not only were there no outside investigators hired, but Susan hasn’t been seen or heard from since she first left the hospital that first day.

Angered by this perceived betrayal, Lewis asks Ney to look into it. Outside in the hallway, Ney finds Morello and Bundy waiting, where they all exchange another round of evil smirks and handshakes.

Meanwhile, as a gambler, Lewis knows when he’s up against a stacked deck and decides to take Ney's deal. After accepting the plea-bargain, Lewis heads to jail for a crime that was legally self-defense, a victim of a tangled frame-up that Lewis vows to unravel and avenge -- if he lives long enough to do it, that is…

While breaking down the career of film director Phil Karlson, Wheeler Dixon described the nuts ‘n’ bolts of his oeuvre thusly: “In Karlson’s best films, a truly bleak vision of American society is readily apparent; a world where everything is for sale, where no one can be trusted, where all authority is corrupt, and honest men and women have no one to turn to but themselves if they want any measure of justice,” said Wheeler (Sense of Cinema, June, 2017).

“For Karlson, everything comes with a price -- in blood, death, and betrayal. That’s the America that Karlson sketched out for us in the 1950s, and it’s more than relevant today. In his finest work, Karlson seems to be saying don’t you believe what they tell you. Authority figures only look out for themselves. There are no easy answers. You won’t get what you deserve, and you won’t even get what you fight for. You’ll get what you can take, and that’s got to be enough.”

Phil Karlson.

As to how Karlson came to these conclusions, well, that’s kind of a long story. And so, we begin at the beginning. See, Karlson’s father always wanted his son to be a lawyer when he grew up, a far cry from his youthful pursuits on the streets of 1920s era Chicago, where a young Philip Nathan Karlstein served as a lookout for an illegal distillery during the days of Prohibition.

“I was born in Chicago, and I was raised in Chicago, and I went through the days of the killings and whatnot in Chicago,” related Karlson in an interview with Todd McCarthy and Richard Thompson (King of the Bs: Working Within the Hollywood Studio System, 1973).

“I remember getting twenty-five cents to stand on a corner, and if the cop was on this side of the street, to whistle real loud; and if he was on [the other] side of the street, just to whistle softly. I was keeping a brewery going by a little whistle. When I got a little older, in high school, I actually came out of a theater, and the man in front of me was gunned down -- a car pulled up alongside and gunned him down. They put five bullets in this man and he lived. So, I sort of saw all that.”

After finishing high school, Karlson attended the Chicago Art Institute for a spell. In between painting classes, he also pursued a brief career in vaudeville as a song and dance man; but he was destined to wash out on both artistic endeavors. As he told John Wakeman, “I had a one man show and never sold a painting.” (World Film Directors: 1890-1945, 1987.)

Thus, looking for a little financial stability, Karlson finally fulfilled his father’s wishes, moved to Los Angeles, and enrolled at Loyola Marymount University to pursue a law degree. Despite earning an athletic scholarship, Karlson supplemented his studies by selling a few ideas and gags to Buster Keaton; and he soon ingratiated himself well enough with the Silent Screen legend to be invited to hang around the Keaton lot on a regular basis.

Thus and so, by 1927, an enamored Karlson was ready to switch vocations yet again. He dropped out of law school his junior year and landed a part-time job at Universal for $18 a week in the prop department, telling McCarthy, “[I was] washing toilets and dishes, whatever the hell they gave me."

Other sources claim Karlson switched to night classes and earned his law degree but never got around to actually taking the Bar Exam. Turns out he wouldn’t need it as Karlson soon left his toilet brush behind and started moving up the studio food chain, because, according to Wakeman, he soon “talked his way into a number of short-lived assignments as an assistant [in other departments].”

Karlson would expand upon this further when he told Kevin Thomas, “I started liking what I was doing. Unfortunately, the people I was working with were afraid I’d take their jobs, so I kept being transferred from one department to another until I was shoved onto a stage, [where] I became an assistant editor and an assistant director.” (The Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1974.) And that last one would stick.

Karlson’s first credited go as an assistant to the director (as Phil Karlstein) was for Ben Stoloff’s version of Destry Rides Again (1932), starring Tom Mix and Claudia Dell, meaning not to be confused with the more famous George Marshall version that came out in 1939, which was headlined by James Stewart and Marlene Dietrich. He would also sell a script to Will Rogers, which concerned the head janitor of the Warren J. Harding White House during the notorious Teapot Dome Scandal (1921-1923). And while this was a huge step forward, the film was stillborn due to Rogers’ tragic death in 1935, victim of a plane crash.

From there, Karlson assisted or shot second-unit for the likes of Karl Freund on The Countess of Monte Cristo (1934), Albert Rogell’s The Last Warning (1938) and Tay Garnett’s Seven Sinners (1940). But he would make the most hay with another trio of directors: Stuart Walker -- Great Expectations (1934), Werewolf of London (1935), and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1935); Otis Garrett -- The Black Doll (1938), The Lady in the Morgue (1938), and The Last Express (1938); and Joe May -- House of Seven Gables (1940) and The Invisible Man Returns (1940).

But Karlson’s biggest break -- a break that would eventually land him in the director’s chair -- came while assisting on Arthur Lubin’s In the Navy (1941), an early vehicle for the comedy duo of Bud Abbott and Lou Costello. As Karlson explained to McCarthy and Thompson, “I had been an assistant director on the Abbott and Costello pictures and I had gone to Lou Costello at times -- very gutty to do this, actually, without checking with the director, writer, or producer -- and I would suggest gags to him. He would [then] go in [with my ideas] and tell the director this is what he wants to do, and he would do it and he would get laughs.”

But then history threw up a roadblock when making motion pictures took a backseat with the looming possibility of America’s entry into World War II. And so, in 1940, Karlson abruptly quit his job at Universal and joined the U.S. Army Air Corps as a flight instructor. Then, after the events of Pearl Harbor, Karlson continued to serve as a fighter pilot until he suffered serious injuries in a plane crash in 1943, which officially ended his time in the service.

Upon his release from the hospital, Karlson tried to get his old job back at Universal, where he bumped into Costello, who had been trying to track him down for the last two years with a job offer. Seems Costello wanted to dabble in producing and pegged Karlson to direct a film for him. This resulted in the wartime screwball comedy, A Wave, a WAC and a Marine (1944), where a case of multiple mistaken identities snowballs into all kinds of hijinx.

"One of Hollywood's open secrets is that Lou Costello is a silent partner in producing a $150,000 comedy at Monogram while he he and Bud Abbott are co-starring in a million dollar comedy at MGM," reported Harrison Carrol for his column, Your Hollywood (The Beatrice Times, May 4, 1944). "Lou is on the set this week watching director Phil Karlstein shoot a scene with Elyse Knox, Ann Gillis and Billy Mack. Karlstein is making his debut. He was an assistant on three of the Abbott and Costello movies at Universal. 'This was a service story at first,' says Costello. 'We found out there would be a lot of red tape, so we changed it to a back stage and a Hollywood story. We liked the original title, so we took care of that by having all the characters join the service at the finish.'"

Said Karlson, “It was a nothing picture, but I was lucky because it was for Monogram and they didn’t understand how bad it was because they had never made anything that was any good.” (King of the Bs, 1973).

Monogram, along with Grand National, Republic Pictures and Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC) were the backbone of Hollywood’s bottom feeders, colloquially known as Poverty Row, who provided no-budget B-pictures to fill in the slots between the major studio releases. Thus, while unglamorous, it proved a land of (low-rent) opportunity for Karlson after his debut feature.

“They [gave] me another story that I flipped over,” said Karlson (King of the Bs, 1973). “Oh, I knew this was surefire. So I got into production as fast as I could with the second picture, and the second picture was a tremendous hit. It was called G.I. Honeymoon (1945),” another comedy headlined by Monogram's current It Girl, Gale Storm, whose efforts to make her marriage with her new G.I. husband *ahem* “official,” in a biblical sense, are constantly derailed and thwarted by Army protocol.

He would direct Storm again in Swing Parade of 1946 (1946), which also featured the Three Stooges, who were on loan to Monogram from Columbia. Odds are better the trio were being punished for some perceived sin against Harry Cohn and his studio. (More on him in a sec.)

But Karlson would spend most of his time in the Monogram trenches on their B-programmers and franchises, churning out vehicles for Charlie Chan -- The Shanghai Cobra (1945), his first official credit as Phil Karlson instead of Karlstein, and Dark Alibi (1946); The Shadow -- Behind the Mask (1946) and The Missing Lady (1946); and The Bowery Boys -- Live Wires (1946) and Bowery Bombshell (1946).

“None of Karlson’s Monogram films are really any good; but all have flashes of brilliance,” said Dixon. “In such early projects as the Charlie Chan vehicles, the best sequences are usually wordless, and often come at the beginning of the film, as characters and setting are established with a series of heavily angled, noirishly lit sequences that sadly soon become a dim memory once the film’s dialogue-heavy script kicks in.”

Karlson had worked with most of the Bowery Boys before when the original Dead End Kids split into The East Side Kids and The Little Tough Guys, who wound up at Universal, where Karlson assisted Joe May on You’re Not So Tough (1940). Now, the schism and reunification of the Dead End Kids is rather fascinating but would take way too long to explain here. Maybe if I ever get around to writing up Bowery at Midnight (1942) or Ghosts on the Loose (1943) we can dig into it further. Maybe.

“They had very little money,” Karlson told McCarthy about working for Monogram. But, “They knew what they were doing because there was a certain class of picture they were going to make and they weren't going to make anything any different. They had their own distribution. They were very liquid, that company. They would have their money back before they even started because they got so much money from their exchanges. They really were well organized and they knew how much they could spend.” And every once and a while, there’d be a bona fide opal in the offal.

As their careers dried up, a lot of former A-list actors for the majors also found themselves put out to pasture and slumming for Poverty Row, trying to extend their careers just a bit longer because, well, an actor has to eat, too. As a case in point, we have Kay Francis, a former ingenue of both Paramount and Warner Bros in things like Ernst Lubitsch's Trouble in Paradise (1932) and Archie Mayo’s Give Me Your Heart (1936).

But then in 1938, Francis had the ignominious honor of joining the likes of Dietrich, Joan Crawford, Fred Astaire and Katherine Hepburn on the Independent Theatre Owners Association’s published list of stars they considered to be pure “box office poison” in The Hollywood Reporter (May 16, 1938) pictured below.

And while most of those stars listed overcame this branding, Francis did not. And after starring in Four Jills and in a Jeep (1944) for 20th Century Fox, which co-starred Martha Raye, Mitzi Mayfair and Carol Landis, who wrote the book on which the film was based, chronicling their efforts for the USO during World War II, Francis would sign a three picture contract with Monogram as both a producer and actor.

The first film, William Nigh’s Divorce (1945), was a seething melodrama that saw Francis portray a predatory five-time divorcee, who returns to her small hometown to torpedo the marriage of a childhood boyfriend (Bruce Cabot) and make him husband number six.

The film was a success for Monogram both commercially and critically. The New York American (November 7, 1945), called it a “motion picture of unusual excellence, judged from any standpoint (-- meaning something coming from Monogram). Miss Francis, as the much-married divorcee of the story, is a poised, ruthless woman of the world and displays all the seductive artistry which long ago established her as a star of the first rank.”

Then things really got interesting with her next two, “ripped from the headlines'' features. The first, Allotment Wives (1945), also directed by Nigh, saw Francis as the ringleader of a conspiracy to commit fraud by cashing in on the death benefits of soldiers and sailors fighting and dying overseas, sometimes marrying one of her girls to several enlisted men at the same time in order to fleece even more money.

Her third and final feature hit a little closer to home. In Wife Wanted (1946), Francis played a fading starlet who gets hooked up in the sordid machinations of a real estate developer (Paul Cavanaugh), whose true source of income is running an ersatz Lonely Hearts Club, where he defrauds and blackmails socially awkward people into sham marriages. That is he was, until it was broken up by a repentant Francis and a crusading reporter (Robert Shayne).

Karlson would sub in for Nigh on Wife Wanted. According to Lynn Kear and John Rossman (Kay Francis: A Passionate Life and Career, 2006), “Francis didn’t like the script, and she and Karlson immediately went to work on a new one.”

As Karlson told McCarthy, “You never get to know anybody in a B-movie. That's why I tell you I broke everything down in acts. First act, I want to develop characterization, so you get to know the people, then go on with the story. It's a slow way of telling a story, but it's the only honest way to tell it unless you happen to have that great writing we're talking about, where a character can develop in front of your eyes as you go along. Well, that's great writing. That doesn't happen very often,” said Karlson, who often pitched in on his scripts.

“It's impossible for me to do a picture unless I work with the writer. In fact, I must work on the script with the writer. I think all directors should do that; there must be a meeting of the minds. It's too bad when you have a falling apart, like it happens every once and awhile, and a picture is botched up because the director had a completely different theory on what the writer was trying to say. When that happens, you have a bad picture.” (King of the Bs, 1973).

Wife Wanted would be Francis’ last feature. Dixon called the film “grimly efficient.” And while “it was not well received by the public, [the film] offered the first real taste of how acerbic Karlson’s vision of American life could be, something he would expand upon in his later work.”

Now, Monogram almost made the leap out of Poverty Row and into second tier studio status with the release of Dillinger (1945). A co-production with the King Brothers, this “sensationalized crime drama” that featured Laurence Tierney as the fabled outlaw bank robber was a runaway success and garnered an Academy Award nomination for Philip Yordan’s screenplay -- a rarity for lowly Monogram. And the film would set a precedent in style for this type of procedural crime drama.

But try as they might, Monogram couldn’t make lightning strike twice and failed to cash in on this opportunity like Columbia had done in the 1930s, when they hitched their wagon to Frank Capra, who helped them go legit with It Happened One Night (1934), Lost Horizon (1937) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

But never fear! In less than a year, Monogram was ready to take another shot at respectability when Walter Mirisch managed to convince his boss, Steve Broidy, the head of the studio, that the days of low-budget programmers were ending and they needed to expand their horizons. They needed to think bigger. And that meant spending more money. Broidy agreed and started the machinations that would soon transform Monogram into Allied Artists. But first they would need a film to test these waters before fully committing, and someone to make it. They chose Karlson, and the film would be Black Gold (1947).

“[Monogram had] put me under contract,” Karlson explained to McCarthy. “They were paying me $250 a week, and they figured, if I do enough pictures, they'll be paying me nothing, which was true. I think I did eighteen pictures one year. Well, you can't make eighteen half-hour shows in one year anymore. That's how fast we were turning them out. I'd make 'em in four days, five days, six days, seven days, and when I got a chance to do Black Gold, well, this was a career [defining moment].”

Based on a true story, the film concerned prejudices against minorities -- more specifically, Native Americans; and more specifically still, one who owned a horse called Black Gold, a long shot that would win the 1924 Kentucky Derby. The film had a budget of $450,000 -- nearly six times what was usually expended on a Monogram feature ($80,000). It was also the first Monogram film to be shot in color, albeit in the cheaper Cinecolor instead of the standard Technicolor. (Fun Fact: Principal photography on Black Gold had to be delayed for two weeks because of a shutdown at the Cinecolor processing plant.)

“I got an opportunity there to make one of the first pictures, I think, in which a social statement was made on the screen,” Karlson told McCarthy. “The average guy that would go see a motion picture in those days went to see entertainment. [Before], we weren’t making statements, we were making cops ‘n’ robbers and good guys and bad guys. But to look at something and see the truth, for a change, was something that was unusual in those days.”

The film would be an early starring vehicle for Anthony Quinn, one of the most criminally underappreciated actors in my book, and would take nearly a year to complete, including location footage shot at Churchill Downs. Meanwhile, that very same year, Karlson would direct four other pictures for the rapidly evolving Monogram -- the aforementioned Bowery Bombshell, The Missing Lady, Wife Wanted, and Kilroy Was Here (1947) -- another post-war comedy based on service slang and some notorious graffiti.

“I made four or five pictures while I was shooting Black Gold. I did Charlie Chans, I did Shadows, I did the Kay Francis picture,” said Karlson (King of the Bs, 1973). “It shows you what went on at this little company at that time. It took me a year to make Black Gold. I wanted the seasons. I went to Churchill Downs for the Derby and had to do the races here, and I had to get some desert scenes. A lot of time lapses in the picture.”

Black Gold would be the first picture to debut under the new Allied Artists banner, who followed it up with the even more expensive It Happened on Fifth Avenue (1947), a Christmas-centric comedy directed by Roy Del Ruth, which cost the studio $1.2 million and would gross about $1.8 million. Thus, while it did make a profit, the newly christened Allied Artists would scale things back just a bit with budgets ranging from $500,000 to $850,000 for the foreseeable future as they successfully elevated themselves out of Poverty Row.

And with that success, Karlson took a step up, too, landing at Columbia for a trio of pictures; two westerns -- Adventures in Silverado (1948) and Thunderhoof (1948), and Ladies of the Chorus (1948), a raucous musical comedy, which was one of the first featured roles for a pre-rhinoplasty Marilyn Monroe. As Karlson told Thomas, “It was the first time I ever heard an audience whistle and applaud throughout a sneak preview. I felt sure that Marilyn would be a big star someday.”

And, according to Dixon, Karlson was so convinced that Monroe was a burgeoning major talent he tried to convince Cohn to keep her under contract. But Cohn didn't agree, letting her current contract expire, and, to his “everlasting regret,” he let Monroe slip away to 20th Century Fox, where Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and The Seven Year Itch (1955) awaited.

But just when Karlson seemed to be gaining traction at Columbia, he had a falling out with Cohn, who fired him halfway through the filming of Assignment: Paris (1952). However, Karlson was then immediately snatched up by Edward Small, an independent producer, who had been in the industry since 1929 under several different banners (-- Faultless Pictures, Asher Small Rogers, Reliance Pictures, and Edward Small Productions), hitching his wagon to several different studios for distribution, including Columbia and RKO, but did most of his work for United Artists.

“I did eight pictures for [Small],” said Karlson (King of the Bs, 1973), who had worked with Small while still at Columbia. “Oh, he's a fantastic guy, actually more astute than most people ever gave him credit for. Probably, in his field -- and he made some very good films -- the most successful producer in our entire industry.”

The Grand Island Independent (February, 1949).

Small’s track record included I Cover the Waterfront (1933), a breakout role for Claudette Colbert; The Man in the Iron Mask (1939); the original Brewster’s Millions (1945); and the unheralded crime film Raw Deal (1948). His first collaboration with Karlson would be The Iroquois Trail (1950), a riff on James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, which was followed up by the western The Texas Rangers (1951). They would also team up for a couple of swashbuckling adventure yarns with Lorna Doone (1951) and The Brigand (1952).

But it wasn’t until Small assigned him a trio of hard-boiled crime pictures that Karlson really solidified his signature quirks, his penchant for scathing social commentary, and a propensity for violence, starting with Scandal Sheet (1952).

Based on Samuel Fuller’s novel The Dark Page, it’s hard to find the hero in Scandal Sheet, which sees the publisher of a shady tabloid (Broderick Crawford) watch helplessly as one of his dogged and unscrupulous reporters (John Derek) piece together the clues to unravel the Lonely Hearts Murder -- a murder the publisher committed.

Plot wise, the film echoes The Big Clock (1948), only there it's the victim of a frame-up that unravels the mystery and fingers the real killer (-- and it's also one of my favorite Ray Milland vehicles). What sets Scandal Sheet apart is the glaring spotlight it shines on the machinations of getting the story, no matter who gets hurt, into print, where “the facts” are hammered to fit the publisher’s narrative, and the public’s voracious appetite for such salacious things.

In the opening scene, the reporter and photographer dupe a witness into giving them a statement on a grisly crime scene, thinking they’re cops. The murders are rather blunt, but the ink that is bled from them is made all the more lurid. Here, Karlson and cinematographer Burnett Guffey turn the audience into another voyeur for the camera’s unflinching eye, giving us an unfiltered view of the flop sweat, the sleaze, and the slain as things played out.

Karlson would then team up with actor John Payne on Kansas City Confidential (1953) and 99 River Street (1954). Payne was a former crooner for Fox, who had aged his way down to the minors like Francis.

In the first film, a truck driver (Payne) is framed for an armored car robbery. After a brutal interrogation by the cops, an alibi gets him released, allowing him to track down the real robbers in Mexico. A crazy tale of corruption, hidden identities and triple-crosses, Kansas City Confidential was shot with a documentary flair by George Diskant, adding a metric-ton of verisimilitude as things unravel. It also had a supporting cast to die for with Colleen Gray, Preston Foster, Neville Brand, Lee Van Cleef and Jack Elam.

As for 99 River Street, it’s another race against the clock as a police dragnet encircles a man framed for a murder. As The New York Times (October 3, 1953) summed it up: “In this stale rehash, John Payne is a cabbie seething with dreams of what he might have been in the boxing world. He is saddled with a wife who is as shallow, larcenous, and amoral as an oyster. There is the bag of stolen gems, the murder of Mr. Payne's wife, played juicily by Peggie Castle, and his frame-up. Naturally lovely Evelyn Keyes helps him out of these pestiferous circumstances, all the while acting as though she were animated by electric shocks.”

And this critical pasting continued, saying the film was “one of those tasteless melodramas populated with unpleasant hoods, two-timing blondes and lots of sequences of what purports to be everyday life in the underworld … To say that this film is offensive would be kind; to point out that it induces an irritated boredom would be accurate. The defendants in this artistic felony are Robert Smith, the scenarist, and Phil Karlson, the director. It is interesting to ponder how Mr. Karlson managed to slip some objectionable scenes past the production code. Maybe it was just artistic license.”

Don’t feel bad, I had to look up ‘pestiferous’ too -- though I would hardly call the circumstances in the film a ‘nuisance’ nor ‘annoying’ (-- and seriously, how "amoral" can an oyster really be?) But I do find it interesting that everything this anonymous reviewer took the film to task for is why it is celebrated today. A highlight for sure is Castle, who always put the fatale in the femme most righteously.

The film was shot by Franz Planer, another in a long line of gifted, if unsung, cinematographers Karlson got to work with. “We had a great simpatico,” Karlson told McCarthy, explaining his modus operandi behind the camera.

“I must tell you, I direct with very little improvisation. Well, I do use improvisation because you must improvise at different times to get what you're really looking for, because the written word can't always be told just the way we put it down. I must do the picture twice in my mind, I mean from start to finish. Just the way I see it, the entire motion picture. When I start shooting the picture, I still have this overall picture in my mind. Now, once I start shooting, I want to make it better than what I had in mind, because I had some wonderful tricks in mind. I had an overall idea of what the picture should look like, but now I've got to improve on it. And I must tell you, I never have. I've never been satisfied with anything I've made, but I try to improve on what I've already pictured.”

As for the levels of violence and blood-letting Karlson seemingly got away with at the time, McCarthy asked the director to expand upon “the kind of violence that brings home the point of how rough and how disorganized violence is, and how much destructive energy is loosed,” giving the example of a fight between Payne and the villain (Jack Lambert) in 99 River Street. “You really got a notion of how destructive two people can be,” said McCarthy.

Said Karlson, “Violence for just violence's sake, to me, on the screen is probably the most horrendous thing you can do. But, I think, when it belongs, you should show it and you shouldn't pussyfoot around it. You should put it on there the way it happened. When people are shot, they bleed.” But it wasn’t always about gunplay or a fist to face. “I can get violence without anybody touching anybody. I can set up three men in this room waiting for a man to walk in and go to a girl on the corner someplace, and you know that this man is dead.”

Karlson would then assemble everything in his accrued cinematic arsenal and then unleash it on his next feature, teaming up with Walter Mirisch on The Phenix City Story (1955). Based on the real-life assassination of Albert Patterson, a candidate for Alabama’s Attorney General, Patterson (John McIntire) was running on a reform platform; the main goal of which was to clean up and clear out the organized crime elements that had turned Phenix City into a vile den of vice, prostitution, gambling and violent political corruption. But this tragic turn of events backfires when Patterson’s son (Richard Kiley) takes up the fight to avenge his father by taking out the mob, despite the danger to himself and his family.

And while filming on location in Alabama, Karlson would face some dangers of his own, telling Charles Mohan (The New York Times, May 12, 1974), “When I was finishing The Phenix City Story, I started to receive threatening phone calls. The callers said, ‘Don’t come out of your hotel or you'll get killed.’" And so, "I began to shoot scenes at three or four in the morning, when nobody was around.”

The Grand Island Independent (January, 1956).

But then, “One morning after the shooting was over, I went to a local club to have a drink. A very attractive woman came up to me and said, ‘Mr. Karlson?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ She hit me across the face with her handbag, and I could feel it, [it] had a gun in it. My teeth flew out; I fell over. I reached out to grab her -- I could easily have choked her to death -- and two fellers came and hit me again. I crawled out of there more dead than alive,” said Karlson.

“What the people of Phenix City went through before that notorious vice and gambling town was spotlighted by the murder of Albert Patterson, its leading anti-vice crusader, is vividly and terrifyingly pictured in an uncommonly good little film," trumpeted Bosley Crowther (The New York Times, September 3, 1955).

“In a style of dramatic documentation that is as sharp and sure … scriptwriters Crane Wilbur and Dan Mainwaring and director Phil Karlson expose the raw tissue of corruption and terrorism in an American city that is steeped in vice. They catch in slashing, searching glimpses the shrewd chicanery of evil men, the callousness and baseness of their puppets, and the dread and silence of local citizens. And, through a series of excellent performances, topped by that of John McIntyre as the eventually martyred crusader, they show the sinew and the bone of those who strive for decent things.”

Thus, as Karlson said, the violence of his pictures was not gratuitous but used as a framing device to show how hard it is to overcome it. As Crowley points out, “There is evidence of sin aplenty in this startlingly realistic film, and the showing of violence and murders is as strong and ugly as it can safely be on the screen. But the brilliance and beauty of it are not in its detail of crime but in its capture of a feeling of real corruption, of civic and social paralysis, and a sense of the sacrifice and effort that men must make to wage a clean-up crusade … There are those who may feel this vivid chapter out of the recent annals of American corruption and crime to be too ugly to acknowledge. That may sentimentally be. But it is a fine piece of picture journalism -- and a tautly made movie to boot.”

I think noted critic Andrew Sarris put the hammer to the nail best, saying, “Karlson was most personal and most efficient when he dealt with the phenomenon of violence in a world controlled by evil. His special brand of lynch hysteria establishes such an outrageous moral imbalance that the most unthinkable violence releases the audience from its helpless passivity.”

Ergo, Karlson had really found the temperature with The Phenix City Story, and he appreciated the freedom Allied Artists gave him to pull it off, whether they realized it or not, telling McCarthy, “They didn't know how much good they were doing me, because I was experimenting with everything I was making, trying to get my little pieces of truth here and there, that I was trying to sneak in these things that they weren't ever conscious of. In fact, they were just the opposite. They were the most conservative, right-wing guys you ever could see. They had no idea what was going on as far as the actual content was concerned. Later on, with Steve Broidy, and we started getting the Mirisches in there, then I started making these pictures that really said something.”

Also, one cannot and should not minimize the efforts of cinematographer Harry Neumann on The Phenix City Story. And Karlson would agree, telling McCarthy, “He was an excellent cameraman. He was what we call a lab man. When you get a cameraman who's started out in the lab, not on the set, he understands development and he knows lighting; he knows what you need. He was of that breed.”

Here we'll note that one of the biggest fans of The Phenix City Story was Desi Arnaz, who invited Karlson to helm a new TV-series for his Desilu Productions. The series in question was The Untouchables (1959-1963), another true crime tale of Elliot Ness’s crusade against the Chicago mob in the 1930s. Arnaz wanted that same kind of realism seen in The Phenix City Story, but Karlson initially turned him down, citing he’d be too hamstrung by the TV-censors, who wouldn’t allow him to tell this tale the way he wanted to.

TV Guide (October 15, 1959).

But Arnaz was persistent, telling Karlson to let him worry about the censors and gave him carte blanche on everything else. But, “I wouldn't do TV,” said Karlson (King of the Bs, 1973). “That wasn't my bag. I was a motion-picture director and it's sort of a comedown to do TV.” But Karlson eventually agreed to shoot the pilot, which set the tone of the series to follow, before turning things over to Quinn Martin.

Meanwhile, after the success of The Phenix City Story, Karlson was welcomed back to Columbia and into the open arms of Harry Cohn. Now Cohn, you remember, missed out on Marilyn Monroe but was currently doing his damnedest to make his own blonde bombshell sensation out of Kim Novak. Karlson would direct Five Against the House (1955), a vehicle for Novak, whose plot presciently predicted Ocean’s 11 (1960). Here, a bunch of college buddies decide to knock-off a Reno casino as an elaborate practical joke -- only to find out one of them wasn’t laughing.

Karlson would then follow that up with another taut thriller, Tight Spot (1955), where a witness (Ginger Rogers) is coerced into testifying against the mob but has the misfortune of being guarded in a safehouse by a corrupt cop (Brian Keith). And in The Brothers Rico (1957), a former mob accountant (Richard Conte) discovers, to his eternal regret, that one can never really leave that particular profession, beating Michael Corleone to the ‘pull-me-back-in’ punch by nearly thirty years.

And with his next feature, Gunman’s Walk (1958), it appeared that Karlson was poised to finally earn himself a shot at an A-picture for Columbia. Apparently, Cohn was so moved by this tragic tale of a former gunslinger (Van Heflin), who is left to raise two sons in a transitioning landscape on his own, one who grew up bad (Tab Hunter) and the other meek (James Darren), he burst into tears while screening a rough cut. “There was no tougher man in the whole world, and I had the pleasure of seeing this man sit in a projection room, with (the film's producer) Freddie Kohlmar and myself, crying at Gunman's Walk,” recalled Karlson (King of the Bs, 1973).

“At the end of that picture, he was literally crying. Harry Cohn crying! Freddie Kohlmar got up; he was so embarrassed he walked out. Got outta there real fast. Then I started to get out and he stopped me … He was so moved by that picture because he had two sons and this was a story about a father and two sons. He identified completely with that motion picture and he said to me, ‘You're going to be the biggest director in this business and I'm going to make sure you are.’”

Alas, and once again, the cruel hand of fate stepped in; for not long after this screening, Cohn, plagued by an enlarged heart, was struck by a second heart attack and died while in transport to the hospital. Thus ended the prickly legend of Harry Cohn, which could possibly be best summed up by Red Skelton while attending the mogul’s star-studded-to-overflowing funeral, where he apocryphally quipped, "It proves what Harry always said: Give the public what they want and they'll come out for it.”

Thus, with Cohn’s death, that promised promotion died with him. And as the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, Karlson kind of entered the wilderness years of his career as he slid from 'breakout potential' into near anonymity as an also ran.

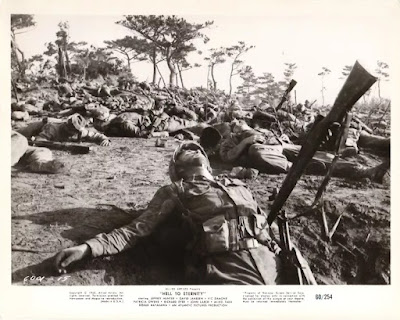

The decade started strongly back at Allied Artists with Hell to Eternity (1960), another tale of prejudice. Based on a true story concerning Guy Gabaldon, in the film, as a teen, an orphaned Gabaldon (Jeffrey Hunter) is adopted by a Japanese-American family; and over the years learns their language and customs. But after the events of Pearl Harbor, Gabaldon enlists in the Marines to do his patriotic duty only to see his family rounded up and sent to an internment camp due to their ethnicity.

Given his upbringing, Gabaldon serves as an interpreter but is torn between the loyalty to his adoptive culture and the enemy that is ruthlessly killing all of his friends. But after a crucible of fire, Gabaldon wises up and winds up saving a lot of lives during the Battle of Saipan, nearly single-handedly convincing over 1300 Japanese soldiers and civilians into surrendering instead of committing mass suicide in the face of the overwhelming enemy, earning him the nickname, The Pied Piper of Saipan.

“Every successful picture I've ever made has been based on fact,” Karlson told McCarthy. “Sure, plenty of fiction enters into it, but the basic idea is true.” And Karlson was particularly proud of Hell to Eternity, calling it “one of the most important pictures that I may ever make because it was the true story of the Nisei, what happened in this country.”

However, it should be noted that Karlson and the studio would trade in one form of whitewashing for another, casting Hunter to play Gabaldon, who was Hispanic. And while it does get tripped up in a lot of war movie cliches and a romantic subplot in the second half, the first half that deals with the family and the unjust internment camps is a lot more interesting, grounded and touching.

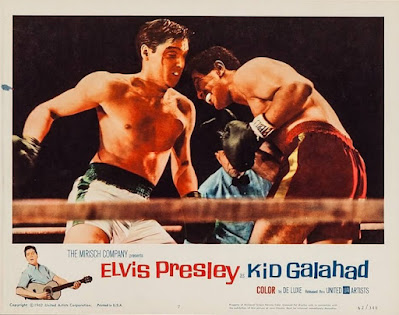

Karlson would follow that up with another vehicle for Hunter, Key Witness (1960), an overwrought thriller that tried for that Karlson verisimilitude but it gets lost in that MGM gloss. And then came a couple features for United Artists, one a melodrama, The Young Doctors (1961), the other was a musical dramedy, Kid Galahad (1962), a post-service Elvis Presley pugilist picture from his Action-Man phase that wasn’t THAT terrible.

There was also Alexander the Great (1963), a notorious failed TV-pilot, with William Shatner as Alexander, who was flanked by the likes of Adam West, John Cassavetes, Simon Oakland, Joseph Cotten, and poor man’s Charles Laughton, Cliff Osmand, as his nemesis, the Persian general, Memnon. Nowhere near as bad as its dubious reputation, it comes off as a sword and sandal version of The Rat Patrol (1966-1968) and well worth a spin -- if you can find it.

Karlson would also direct The Silencers (1966), the inaugural entry in the Dean Martin as Matt Helm spy-spoofs. How did it turn out? Well, according to Dennis Powers, “If anything can put a stop to the current secret agent film craze, The Silencers ought to do it. If the craze survives this one, kids, we’re really in trouble. This movie abandons all pretense of believability or suspense and coasts along confidentiality on the assumption that its own vulgarity will see it through.” (The Oakland Tribune, March 17, 1966.)

Loosely -- and I mean LOOSELY -- based on the books by Donald Hamilton about a secret agent assassin, strangely enough, the idea to put a comical spin on The Silencers might’ve come from Karlson. As the rumor mill goes, the reason Richard Widmark fired him off of another espionage picture, The Secret Ways (1961), was over creative differences. Widmark wanted to play it straight, while Karlson wanted to camp it up.

Karlson would also initially butt-heads with his producer, Irving Allen, over the very same notions on The Silencers. As he told Thomas, “Allen wanted me to go see The Ipcress File (1965). He wanted me to do The Silencers the same way -- shooting through chandeliers, under tables. I wouldn’t do it. Then, as it turned out, Allen met [that film’s] director Sidney Furie and asked him if he knew my work. ‘Do I know him?’ said Furie, ‘I’ve copied everything he’s ever done.’”

And stranger still, according to Matthew Field, author of Some Kind of Hero: The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films (2015), Karlson was allegedly the first choice of Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman's to direct Dr. No (1962), the inaugural James Bond film, but they couldn’t meet his salary demands, leaving one to boggle and speculate on what that would’ve looked like and the trickle down effect it would’ve had on that entire franchise.

But despite the fan backlash for “ruining” the Hamilton books and the critical drubbing, The Silencers would go on to earn over $7 million at the box-office, easily Karlson’s biggest money maker to date. The film would spawn three sequels, with Karlson returning for The Wrecking Crew (1968). Personally, I tend to take the Matt Helm franchise at face value as the goofs they are and a product of its time, and so, can be enjoyed wholeheartedly on those terms. Despite what the internet tells you, Fellow Programs, a person, like me, and you, can be a fan of both the novels and the films no matter how disparate they may be.This isn't that hard. Stop making it so.

Karlson, Inger Stevens, Glenn Ford (A Time for Killing, 1967).

In between The Silencers and The Wrecking Crew, Karlson was also brought in by Columbia to salvage A Time for Killing (1967), where Union forces track down escaped Confederate prisoners with either side not knowing that the Civil War had officially ended while killing each other. The director he replaced was Roger Corman, who was aspiring to leave B-pictures behind, too, and signed a three picture deal with the studio that went nowhere fast and had him returning to independent filmmaking after only a month of shooting. (He either quit or was fired, depending on the source.)

Said Corman, “Every idea I submitted [to Columbia] was too strange, too weird. Every idea they had seemed too ordinary to me. Ordinary pictures don't make money today [circa 1966] because audiences today are too intelligent. They can see the average for free on TV. You've got to give them something a little more complex artistically and intellectually. To show something you can't see on TV leads inevitably to unusual material.” (The Los Angeles Times, June 10, 1966.)

Karlson would then co-direct Hornet’s Nest (1970) with Franco Cirino. An Italian-American co-production, the plot boils down to, essentially, The Bad News Bears Go to War, with Rock Hudson as a sole surviving commando subbing in for Walter Matthau, who leads a rag-tag group of juvenile partisans to thwart the Nazis and blow up a dam, dragging a reluctant Sylva Koscina along the whole way.

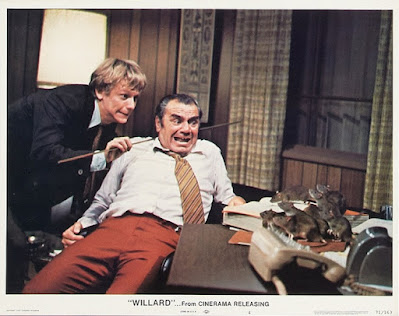

And then Karlson probably hit rock bottom with his next feature, Ben (1972), which was a sequel to Daniel Mann’s Willard (1971), a film about weaponized killer rats. Occluded over time, people tend to misremember that Willard wasn’t a rat but the name of a social misfit / sociopath (Bruce Davison); he was the guy who conditioned a couple of rats occupying the decrepit house he shared with his mother (Elsa Lanchester) into obeying him. Their names were Socrates and Ben.

As the film plays out, Socrates is killed by Willard’s boss (Ernest Borgnine), who usurped Willard’s family business under dubious circumstances. And so, Willard has Ben lead a battalion of rats to exact a lethal revenge for his foe's myriad sins. To cover up his crime, Willard disposes of all the evidence, including drowning all of his captive rats -- only Ben escapes and engineers a righteous rodent revenge of his own.

Based on Stephen Gilbert’s novel The Ratman’s Notebooks, the film was the first theatrical release from Bing Crosby Productions (BCP) after the actor sold his company off to the Atlanta based Cox Broadcasting in 1968. Willard was produced by Charles Pratt and Mort Briskin, and with its surprising box-office success a sequel was in order.

But for some unfathomable reason, Pratt, Briskin and screenwriter Gilbert Ralston decided the sequel should have the killer rat Ben befriend a young boy named Danny (Lee Montgomery). A friendship that soon has the boy banging out a ditty on the piano to celebrate their companionship.

Ben, in turn, runs off Danny’s bullies. But the rats also start wrecking the neighborhood in search of food, which leads to a climax in the sewers with cops armed with shotguns and flamethrowers. Never fear, the film manages to pull off a happy ending as Danny promises to save the critically wounded homicidal rat and nurse him back to health so they can be bestest buds for life.

As a film, Ben is pretty risible. And the only reason most folks remember it at all was because Michael Jackson was brought in to reprise Danny’s “Ode to Ben” for the film’s closing credits. (They originally wanted Donnie Osmond but there were scheduling conflicts.) The song was composed by Don Black and Walter Sharf and would serve as the title track on Jackson’s second solo album, also titled Ben, and would become Jackson’s first number one hit as a solo artist and would garner an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song because of course it was.

Karlson had worked with Sam Briskin on Kansas City Confidential, which was the sole release of the short-lived and ill-fated Associated Players and Producers, a company formed by Briskin, Edward Small and Sol Lesser. Sam Briskin was an old cohort of Harry Cohn since the 1920s and was instrumental in elevating Columbia out of Poverty Row. Briskin was the good cop while Cohn was the bad, and he would take over the studio after Cohn’s untimely death, scoring huge hits with The Guns of Navarone (1961) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962).

Now, I dug around quite a bit but could find no obvious evidence of a familial link between Sam Briskin and Mort Briskin. (If anyone knows better, please let me know.) Either way, it was Mort Briskin who brought in Karlson to direct Ben and his directorial efforts felt a little gun for hire-ish to me. The film just never gels properly as it shifts from the cloying antics of Danny and his creepy puppet shows to the mayhem of the all-out rat blitzkriegs that it tends to give viewers tonal whiplash.

Still, the film made money. Not nearly as much money as Willard, but enough for Pratt and Briskin to bring Karlson back for their next feature -- a no-brainer, really, as the tale they were about to tell was tailor-made for Karlson’s skill-set.

Based on another notorious true-life tale, I guess one could consider Walking Tall (1973) as sort of a stealth remake of The Phenix City Story. Here, the action moves from Alabama to Tennessee and spins the ballad of Buford Pusser, a former professional wrestler who took up law enforcement. Elected sheriff of McNairy County, Tennessee, Pusser made it his life goal to run the Dixie Mafia and the State Line Mob, and their moonshining, gambling and prostitution rackets, out of his jurisdiction. (Sound familiar?)

Then his one man war garnered national attention in 1967, when a mob-hit killed his wife and grievously injured Pusser in a drive-by shooting. He would survive, but as his crusade ground on, Pusser would survive an additional seven stabbings, seven other shootings and one bomb detonation. And he was up for re-election when he signed off on BCP’s proposed biopic.

The Press Telegram (November 30, 1973).

“My partner‐producer Mort Briskin saw Roger Mudd do a 10 minute segment on Pusser on CBS News,” Karlson told Mohan. “Mort called Pusser on the phone that night; he made a date, and flew to Tennessee the following day. He became enormously excited by the idea of Pusser: a man who had been a peaceful citizen until the local syndicate harassed him and his family. He turned on the syndicate, literally armed with a big stick, and smashed up their whole world. When he became sheriff, he drove them out of town,” said Karlson.

“Mort was convinced he should do the story, and Sheriff Pusser promised complete cooperation. I wanted to make a picture for once in which the good guy was the hero -- I was tired of pictures which glorified crooks, petty chiselers, and con men. I was horrified by The Godfather (1972), which sentimentalized the Mafia, and by The Getaway (1972), in which Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw knock off banks, steal thousands of dollars, and ride off into the sunset to loud applause. I thought, let's do something in which people will learn respect for a decent lawman.”

The Jackson Sun (August 13, 1967).

Pusser would serve as a technical consultant on the movie, with the script hammered out by Briskin, Stephen Downing and John Michael Hayes. The film would hew mostly to the truth as Pusser (Joe Don Baker) tried to rally his citizenry to oust those that preyed on them, cheating them out of their money or killing them with poisoned liquor.

This crusade started as a civilian after Pusser visits The Lucky Spot, a local gambling den, who then gets severely beaten, slashed, and left for dead after catching the house cheating at the craps table. When the law refuses to help him, he takes it into his own hands, beating his attackers nearly to death. And after some rousing self-testimony at his trial, Pusser is acquitted. He then runs for sheriff on a reform campaign and wins.

From there, using his soon to be trademarked hickory whompin’ stick to bust heads, break up moonshine stills, or shatter gambling equipment, Pusser’s work begins in earnest. Of course the mob elements pushed back. And the film would ultimately climax with the death of his wife, and the town finally joining him in a mass catharsis as they burn The Lucky Spot down, the symbolic seat of power of the mob, as tears roll down our mangled hero’s face.

“It would be nice to say that Walking Tall is artistically successful, but it really isn’t,” observed Dixon. “It’s a revenge fantasy that looks both cheap and opportunistic, playing up to the worst instincts of mob violence. It doesn’t even hew to the real facts of the Buford Pusser story, though it is ‘inspired’ by real events. Shot by veteran Jack Marta in a simple, stripped down style with minimal subtlety, and slammed together by prolific television editor Harry Gerstad, Walking Tall is a long way from the nuanced brutality of The Phenix City Story, Brothers Rico or Scandal Sheet.”

According to an interview with The Jackson Sun (June 23, 1972), Karlson said directing Walking Tall was part of a package deal, saying, “I promised to do Ben if I got the Pusser picture.” (This explains AH-lot.) “Pusser is a real life hero, a huge man in the mold of John Wayne; a man who is so determined to carry out his own ideas of right that he is willing to die for them. He has been shot, knifed and attacked so many times he looks like a patchwork quilt.”

Karlson would also reflect on Pusser’s determination in the face of tragedy. “When you have your wife’s head shot off and laying in your lap, and your own face shot away, you have to have a lot of determination to keep going. This film will, I hope, accurately portray that kind of grit and dedication.”

The Memphis Press-Scimitar (August 12, 1967).

In real life, no one was ever convicted or even charged for the murder of Pauline Pusser. (Pusser personally thought it was orchestrated by Kirksey Nix, the head of the Dixie Mafia, but could never make it stick.) The film was shot locally but in neighboring Chester County due to the officials of McNairy County being too embarrassed by all the national attention they had been getting for their (alleged) corruption, missing out on all the money that entailed.

It was that kind of attitude that Karlson was shining the brightest light upon, though most audiences missed it, caught up in Pusser’s brutal one man crusade. “I believe that you've got to speak up. It's unfortunate that I have to show it with one person. I would love to see a community get up. This goes back to Carl Foreman and Freddie Zinnemann's High Noon (1952), where the entire community walked away from the guy,” said Karlson (King of the Bs, 1973), referring to Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper), who is left to fight the villains alone because, ironically enough, he had tamed his town into complacency.

“They did the same thing with Buford Pusser, they walked away from him. Once they elected him sheriff and they saw what he was doing, nobody wanted to back him up. Everybody stayed away from him. It's too bad.” But Karlson still managed to sneak these notions in for the film’s finale, where the town is finally shaken out of its lethargy and does the right thing.

“Movies are a form of journalism,” said Karlson (The Jackson Sun, 1972). “I always have a statement to make. I will make one in Walking Tall. The statement will be one of triumph of law and order in a nation that is rapidly deteriorating. The story will be as realistic as we can make it. We will pull no punches. It will show some episodes that will make your skin crawl … But we will portray those things as accurately as our techniques will allow.”

The Los Angeles Times (February 23, 1973).

Like Willard and Ben, Walking Tall would be released by Cinerama Releasing, which was founded in 1966 to distribute films shot in Cinerama but only managed one, Custer of the West (1967), before the format fizzled and gave way to Ultra-Panavision, the one camera Cinerama. But they would continue to distribute films ranging from prestige features like Charly (1968), Hell in the Pacific (1968) and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969) to Amicus horror imports with The House that Dripped Blood (1971), Tales from the Crypt (1972) and Vault of Horror (1973), and other genre fare like The Honeymoon Killers (1970), Straw Dogs (1971) and The Mack (1973).

When the film was initially rolled out in early 1973, Walking Tall didn’t do much business. And so, taking a page from Tom Laughlin and Billy Jack (1972), they kept tweaking the ad campaigns, posters and promotions until they finally struck a grassroots chord, asking, “When was the last time you stood up and applauded a movie?” And then guaranteed viewers that “audiences across America were standing up, applauding and cheering a film called Walking Tall.” And, “It’s the motion picture your neighbors are talking about. Sooner or later, someone will tell you to see it -- unless you tell them first.”

The Los Angeles Times (March 16 and March 21, 1973).

As Bob Thomas noted (The Press-Telegram, November 30, 1973), “Walking Tall was released early this year (1973) in several cities with an ad campaign that stressed raw violence. The result: dismal business. The film played three weeks to sparse audiences in Los Angeles, then headed for burial. The same happened in Chicago and other cities.” But, “Charles Pratt refused to let the film die.”

Said Pratt, “I couldn’t understand it. The manager at the Pantages Theater told me that even when the house was one-third full, the audience stood up and applauded. It was the same everywhere.” And so, “I got mad. I decided you can’t have a picture that the people love and let it die.” And after an intense, three day brainstorming session with Cinerama, they hammered out that new ad campaign, which dumped the violent action and played the film up as a romantic love story. This worked out splendidly as the film soon found its legs, and would be re-booked into cities where it had already washed out with advertising that included a "Special Note to Parents" to see the film twice, once alone, and once with the kids. And no one was more happier with this turn of events than Karlson.

The Oakland Tribune (September 15, 1973).

“We're so proud of what's happening with Walking Tall, and so proud of what happened with Billy Jack (1972),” said Karlson (King of the Bs, 1973). “That in spite of bad exhibition, in spite of a lot of bad advertising and bad-mouthing … In some cases, when that starts, the critics, if they've seen the picture or not, tear it apart. Critics in big cities I don't think can hurt you, because any picture that'll take off today has to be by word of mouth. You have to tell it to somebody else. But in small towns, the critic is important, believe it or not. Where there's only ten thousand, twenty thousand people, they read the paper from the ads down to everything that's in it, and it becomes important there. [In Los Angeles], I don't know if people are even looking at them. There's too many more important things to look at than a review by somebody they don't care about.”

Said Karen Brown (The Macon Telegraph, November 11, 1973), “The movie has no major stars, lacks the explicit sex seen in many films today, has no trick photography, no detailed violence, and the only real music in it comes at the very end.” And yet, “Walking Tall, now in its 21st week at the Mini Cinema, has outlasted such hits as Love Story (1970), The Godfather and The French Connection (1971) and is believed to be the city’s longest running film.” It would run for nearly a year in Atlanta.

Alex Block called it “a moralistic fable shot through with explicit violence and characters bigger than life. The film raises strong emotions from audiences as the ultra-violence is wrapped in an American flag full of law and order and righteousness. If violence is as American as apple pie, Walking Tall is apple pie a la mode.” (The Miami News, April 5, 1973).

In his second review for The Los Angeles Times (April 30, 1974), Kevin Thomas called Walking Tall “a modestly budgeted morality tale of clear-cut good versus evil that required a revised saturation campaign to reach the widest audience possible. Over the past year Walking Tall has become the object of seemingly endless speculation and controversy. Motion picture [insiders] are pondering over what to make of a film that failed when it was exploited for its violence but then succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams when it was resold as a love story,” said Thomas, who was one of the film's earliest champions, who correctly predicted the film would be the sleeper hit of the year.

“The film’s considerable violence has been protested [by those who would] condemn it, [while other] commentators argue the film is inflammatory, making a hero out of a man who takes the law into his own hands," said Thomas. "But the film, like most others, is dealing with myth rather than reality. The reality,” as Karlson wryly pointed out to Thomas, “is that Pusser, rather than eradicating vice, only succeeded in driving it into the next county.”

Karlson also hoped that people wouldn’t get caught up in the violence or Pusser’s one man crusade. “What I hope I've shown is that when Pusser fought the world, it didn't work out; his face has had 17 plastic surgery operations because of all the bullet wounds. He was just torn apart. His wife was killed in cold blood. What I'm saying in the picture is that if you want to get out and get the bad guys, don't do it on your own, find police to support you, get a whole community stirred up first, and let them act along with you.”

On the rebound, Walking Tall would go on to rake in nearly $36 million at the box-office in 1973, and it would stay in circulation for years after and would eventually net close to $60 million. Not too bad on a $500,000 budget. And since it struck such a chord, a sequel was in demand. And with more money to be made, Pratt and BCP was ready, willing and able to oblige. But not Briskin and Karlson, who jumped ship and moved on to a bigger pasture -- and they would take Joe Don Baker with them.

It was announced in late March, 1974, that Robert Evans and Paramount Pictures had signed the trio of Briskin, Karlson and Baker for the film Framed (1975), based on a screenplay written by Briskin. “This is a story about people,” Briskin explained to Jerry Bailey ‘from behind his impenetrable sunglasses’. “It’s a good story, one that everybody can identify with.” (The Tennessean, May 26, 1974).

Based on the novel of the same name by Art Powers and Mike Misenheimer, both were ex-convicts, sent to the State Penitentiary for the murder of a Steubenville, Ohio, sheriff’s deputy. In the novel, their protagonist, Ron Lewis, kills a deputy in a clear case of self defense. Later it’s revealed the deputy was sent there to kill Lewis because he saw something he shouldn’t have and gets sent to jail on trumped up murder charges by the other conspirators.

Joe Kenny called their efforts “a helluva ‘70s crime novel -- lean and mean and doesn’t waste time with inessentials; and brutal, too, with grisly carnage like eyeballs popping out, point-blank blasts to the face by Magnum revolvers, maulings by killer guard dogs, and torture via spark plugs. Hell, it’s even got a fairly explicit sex scene, so what more could you ask for?” (Glorious Trash, May 8, 2017.)

In their adaptation, Briskin and Karlson flipped the narrative of Walking Tall on its head, making a hero out of the kind of person Pusser would have no qualms about caving their head in with his ax-handle, and made a villain out of the local sheriff. Nasty and all kinds of vicious, Framed is sometimes downright uncomfortable to watch, typified by the seedy oral molestation of Susan by the pistol of one of Morello’s goons and that knockdown and dragged-out fight between Lewis and the brutish Haskins in the opening act.

The novel was actually worse, according to Kenny, where the two “beat each other to hamburger, with Ron biting out a ‘chunk’ of the deputy’s neck and finally ripping out his eyeball, which he shows to the dying deputy before throwing it in his face! ‘He was strangling on his own blood and his own eyeball.’” Yikes.

But we've barely scratched the surface yet, with plenty a depths yet to plumb as Lewis gets shafted into a prison sentence by the corrupt sheriff and his cronies, whose end game will be revealed as the rest of this malevolent tale of biblical payback fueled by small town corruption unfolds from there. But that's another tale for another day.

That’s right, Fellow Programs. We finally got too long winded on one of these things -- so long even I kinda forgot what film I was actually reviewing and we kinda broke Blogger. And so, we’re asking you to Stay Tuned for the Second Half of our After-Action report on Framed, where we see where the movie goes and the aftermath for all of those involved. So do come back, won’t you? Thank you!

Originally published on January 20, 2001, at 3B Theater.

Framed (1975): Paramount Pictures / P: Mort Briskin, Joel Briskin / D: Phil Karlson / W: Mort Briskin, Art Powers (Novel), Mike Misenheimer (Novel) / C: Jack A. Marta / E: Harry Gerstad / M: Patrick Williams / S: Joe Don Baker, Conny Van Dyke, Gabriel Dell, John Marley, Brock Peters, Warren J. Kemmerling, John Larch, Paul Mantee, Walter Brooke, Roy Jenson

No comments:

Post a Comment