And to those ends, during the initial autopsy, it's revealed the victim was shot in the throat by a small caliber weapon but the real cause of death was a severe blow to the head and the resulting skull fracture. Also of note: there was trace evidence that the girl recently had sex with at least two different men.

With the rabid media smelling blood and scandal, and a ton of pressure coming from the top brass, the Chief of Detectives assigns the case to Inspector Ramsey (Oliveros), who is explicitly charged to wrap things up as quickly as possible -- and by any means necessary. And while he focuses on "extracting" a confession from some degenerate beach bum, the muddled case also attracts the attention of a recently retired Inspector Thompson.

A cranky and acerbic old coot, Thompson (Milland) doesn't have much faith in the current generation of sleuths; as proof of these doubts, one of Ramsey's better ideas to identify the victim was to put the preserved corpse on public display like some morbid museum piece to see if anyone recognizes her. (And with her face completely gone, I'm assuming he hopes someone will remember the dimples on her rear-end?)

Thus, as the irascible Thompson ingratiates himself into the investigation, he takes up a few discarded clues, including a few grains of rice found in the singed remnants of the yellow silk pajamas the victim was wearing, and then follows his instinctive nose until it leads him to a possible identification of the victim and three probable murder suspects; a college professor, a factory worker, and a waiter, who are all embroiled in a love quadrangle with the same woman, Glenda Blythe.

And as his dogged investigation unfolds, we learn that Glenda seems to move with the breeze from man to man, searching for something she could not define, let alone find it. And as her desperate search for some kind of fulfillment on any level spirals down the drain with one bad decision after another, the woman puts herself in harm's way when this love quadrangle starts to implode all around her. Meanwhile, Thompson narrows down his suspect list to the probable killer, and then puts himself in mortal danger to lure them out of hiding and out into the open...

On a crisp September morning back in 1934, while walking his new prized bull toward his home in rural Albury, Australia, Tom Griffith spotted -- or more appropriately, smelled, something strange emanating from a culvert that ran underneath Howlong Road, which he later testified as reeking of kerosene.

Closer examination proved this smoldering anomaly to be a severely mangled and partially burned corpse, whose head was concealed inside a towel. And after the authorities were called in, they determined the decedent to be a petite female, probably in her twenties, who had been shot near her left eye, which left the bullet lodged in the throat, and whose bludgeoned skull was fractured so badly by what they felt had to be an hand-axe or a tomahawk it left part of the brain exposed.

Due to the charring and the severity of the injuries, with the only real clue to her identity being the partial, oriental-style silk pajamas that survived the flames, identifying the victim proved difficult -- if not impossible, making apprehending whoever had done this despicable deed even harder to catch.

When a couple of missing persons leads didn’t pan out, the local authorities, spurred on by a voracious media blitz and a luridly-lured public, allowed the body of the newly dubbed “Pyjama Girl” to be moved to Sydney, where it was subsequently embalmed, preserved, and in a bizarre, morbid twist, put on public display along with those yellow pajamas with the red dragon on them in an effort to see if anyone recognized her. Hundreds turned out, but no one knew her; and for ten years, not unlike the notorious Black Dahlia murder in America several years later, the media-fed public refused to let the Pyjama Girl case go away.

Constantly reminded of his failure to bring any kind of justice in the case, New South Wales Police Commissioner, William “Big Bill” MacKay, reopened the investigation in 1944; and according to several sources, already had it solved; and whether his “pre-selected” prime suspect was guilty or not was, basically, irrelevant.

Now, the suspect in question, an Italian immigrant by the name of Antonio Agostini, had just spent the last four years in an alien internment camp during World War II. His wife, Linda Agostini, also an immigrant, had disappeared about a week before the Pyjama Girl was discovered, was of similar build, but was ruled out forensically during the initial investigation as one of those missing persons leads -- along with Anna Philomena Morgan, whose tenuous ties to the case might’ve been nothing more than a misguided publicity stunt pulled off by her mother.

Born Florence Linda Platt in a southeast suburb of London, at the age of 19 the girl migrated to New Zealand around 1924 when a failing romance back home went down in flames. She then moved to Australia in 1927, settling in Sydney, where she worked at a cinema and lived in a boarding house near King’s Cross. By most accounts I dug up, Linda Platt kinda got caught up in the wild and woolly Jazz-Age of the 1920s, earning herself a reputation as a boozer and a party girl, who entertained all sorts of men in her flat.

As the decade came to a close, Linda made an attempt to settle down by marrying Agostini in 1930, who insisted they move to Melbourne to get her away from the siren influence of her other myriad lovers and bohemian friends, who weren’t quite ready to give up on the Roaring ‘20s just yet. By all accounts, their marriage was not a happy one; and after four rocky years, Linda Agostini allegedly walked out on him, according to her husband, and was never seen again.

Apparently, MacKay knew Antonio Agostini before the war, who had worked as a waiter at a restaurant he frequented. Then, as the case zeroed in on Agostini, MacKay really put the screws to his nervous suspect. And after a particularly intense interrogation session, and a viewing of the pickled corpse that was actually made-up to look like Linda, a distraught Agostini confessed to killing his wife, saying he had accidentally shot and then killed her after a bad fight while they were still living in Melbourne. To cover his tracks, he then wrapped up the body, drove it to Albury, dumped it in the culvert, saturated it with kerosene, and set it on fire to destroy any incriminating evidence.

Convicted of manslaughter, Agostini served six years and was immediately deported back to Italy once his sentence was up. Meantime, declaring the case solved at last, the body of the Pyjama Girl was finally buried and MacKay moved on. But others, suspicious of his dubious and sometimes brutal tactics, weren’t as easily convinced, felt the fix was in, and still believe in Agostini’s innocence and the true identity of the Pyjama Girl to still be a mystery.

Back in 2004, historian Richard Evans made a strong case for police misconduct in his book, The Pyjama Girl Mystery: A True Story of Murder, Obsession and Lies, by pointing out a ton of discrepancies in Agostini’s confession; and the fact that the Pyjama Girl had blue eyes while his wife’s were brown, and how her dental records suddenly matched up in 1944 when they curiously didn’t ten years earlier. Oops.

So if it wasn’t her, and it wasn’t him, then who really was the Pyjama Girl? And who killed her? Well, there’d been talk of trying to link the body through DNA to the relatives of several other missing persons, but sadly, we may never know for sure who or whodunit.

Now, a true-crime mystery from Australia may seem an odd inspiration for a Spanish-Italian gialli -- a term for a certain breed of Continental thriller, but as La ragazza dal pigiama giallo (The Girl in the Yellow Pajamas, 1978) plays out, one has to wonder if this wasn't just a smokescreen to cover-up the fact that even though scriptwriters Rafael Campoy and Flavio Mogherini -- who also directed the film, used the Pyjama Girl case as an appetizer to get you to the table, the main course would owe much more to another, more contemporary true-crime case, which had been recently sensationalized by a best-selling novel and a big-screen Hollywood adaptation of the same, which was set to be released the year before their film came out, that was just begging to be exploited? Magic 8-Ball says, Maaaaybe…

See, prior to her death at the age of 28, Roseann Quinn was a bit of an enigma. She grew up in New Jersey with her conservative, upper-class, Irish-Catholic parents -- her father was an executive at Bell Labs while her mother was a homemaker. Her Morris Catholic High School Yearbook observed Quinn was, “Easy to meet, nice to know.”

Teaching was her chosen profession, and she became a special needs educator at St. Joseph’s School for Deaf Children in the Bronx during the fall semester of 1969. And by taking night classes, she was halfway to her master’s degree in her chosen specialty by 1972. Quinn taught a class of eight hearing-impaired children, and would often voluntarily stay after class to help them hone their communicating skills.

A representative of the school would later comment in the January 5, 1973, edition of The New York Daily News, “She was a friendly, pleasing personality, not only with the children but also with the other teachers.” And Police Captain John McMahon would later ad during her murder investigation, "She was an affable, outgoing, friendly girl. Her friends were rather diverse. She knew teachers and artists and her circle of friends was a very large, interracial group … She knew an awful lot of people." Thus, by all accounts the petite redhead with the slight limp --- a childhood souvenir from a bout with scoliosis, was an excellent teacher and everyone who knew her seemed to like her despite the young woman’s apparent shyness. But this was only one paradigm of Roseann Quinn.

It was two of her fellow teachers that had talked the young professional into moving into the apartment complex on West 72nd Street in New York City’s seedy Upper West Side, where she eventually met her doom. The building used to be a hotel that was recently converted into cramped studio apartments. Quinn moved in sometime in May of 1972 and quickly made the small space hers, filling it with books, art, and her pet cat. Her apartment was on the seventh floor, near the stairwell. And since there wasn’t much room to breathe inside her humble abode, when she wasn’t working at the school, or going to classes, Quinn often found herself someplace else -- namely the smattering of hole-in-the-wall bars and basement saloons in her neighborhood, like The Copper Hatch or Tweed’s, where she would eventually meet her killer.

Quinn was a very familiar face at Tweed’s, and the owner, Steve Resnick, would later say they had been friends for nearly seven years. Thus, Resnick was fairly familiar with this regular and later commented on how she usually brought a book with her and would just order a glass of wine, find a quiet corner, and then spend the rest of the evening reading or perhaps clandestinely observing the other patrons -- she could read lips, allowing her to “eavesdrop” on the other conversations. But other nights, she’d order a Johnny Walker Red and mingle with the other customers -- some of whom she would hook-up with and eventually take home.

All of this sounds more ominous that it really is -- or should’ve been, but the press really played up the perceived Jekyll and Hyde angle of the ‘devote teacher of the handicapped by day’ and ‘the single girl taking her life into her own hands by merely going out to singles bars and looking for some consensual sex by night.’ Rumors ran rampant amongst the other tenants of her building, about the noises coming from her apartment whenever she brought home yet another one night stand, which soon led to a reputation for “being easy” and engaging in “rough sex,” which only grew worse after one particular incident where one of these sexual encounter went bad.

In an article for The Line-Up -- The Goodbar Murder: A Woman’s Fatal One Night Stand (July 14, 2016), Jessica Ferri recounts how a neighbor claimed “[Quinn] frequently brought home strange men from a nearby bar” and how one night, not long after she had moved in, “upon hearing her screams” the neighbor emerged from her apartment, saw a half-naked man storming down the hallway, the other half of his clothes bundled under an arm, while Quinn was on the floor, sobbing, apparently beaten, disheveled, with a black eye. It’s believed Quinn filed an official complaint against this man who allegedly assaulted her with the police but nothing ever came of it.

Still, Quinn managed to keep her diametrically opposed professional and personal lives efficiently compartmentalized. And that’s one of the reasons why her co-workers found it so strange when she failed to show up for work without any notice after the holiday break on January 2, 1973. No one had seen her since the staff Christmas party back in mid-December. And when she failed to show-up for a second day, when all efforts to contact her failed, they sent a fellow teacher to her building to see if they could locate her. Sadly, and tragically, they did.

When the manager let the teacher into the dimly lit and cluttered apartment on January 3, they found Quinn on the fold-out sofa bed. She was dead; the details gruesome. She was naked, haphazardly covered by a dressing gown, and splayed-out on the thin mattress; she had been beaten and bludgeoned with a ceramic bust that had been modeled after the victim; a gift from one of her artist friends. She was also stabbed 18-times, the punctures leading from her abdomen to her neck and to her head and then back down again, with a knife from her own utilitarian kitchen. And as one final insult, the killer had violated her with a red candle that apparently broke off in the middle of whatever the hell he was trying to do.

The blood on the walls from the arterial spray made for quite the morbid piece of abstract art -- though it lacked a frame like the other paintings hanging on the walls. They also found two rolled up pieces of paper with caricatures of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck doodled on them; somewhat innocuous, sure, but they would prove a crucial piece of evidence in identifying her killer. On the nightstand were several blood-flecked textbooks on sign-language and the last novel she would ever start, and never finish, James Dickey’s Deliverance.

“No case says more about what New York once was and has now become than the murder of Roseann Quinn,” wrote Alexander Nazaryan in his Newsweek article, You Can’t Kill Mr. Goodbar (July 8, 2015). “She was alone in the city, trying to build a life. She had some resources and some ambitions. She was average, but not ordinary. Then came the night of January 2, 1973 -- an encounter in a basement bar, a walk across 72nd Street, the lights of her native New Jersey burning in the distance like the bonfires of an enemy encampment. A few minutes later, she was dead.”

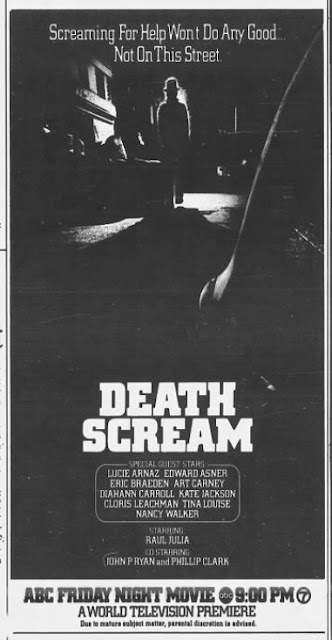

Thus and so, Roseann Quinn became yet another high profile case of a young, pretty, and yes, Caucasian, single working girl murdered in New York City (-- at the same time, sex worker deaths were labeled as NHIs by the police, No Human Involved), and would be forever linked to the double-murder of Janice Wylie and Emily Hoffert, which was dubbed "The Career Girl Murders" by the press back in 1963 and would later serve as the basis for the Made for TV-Movie, The Marcus-Nelson Murders (1973), which in-turn served as a backdoor pilot for the TV-series Kojack (1973-1978); and the notorious Kitty Genovese case, where the press alleged her cries for help as she was stabbed to death outside her home were summarily ignored by dozens of her neighbors, which also inspired another telefilm, Death Scream (1975); and Patrice Leary, a young nurse, who was beaten to death inside her apartment with a hammer; and I will assume since her case remains unsolved is the reason why her sad end never merited a movie of the week. Still, she was in the club. A sisterhood in death, where it became more about how the victim died -- not the victim herself, and even less about who actually killed them.

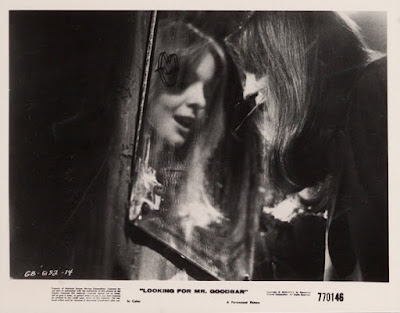

That same year, Esquire Magazine commissioned author Judith Rossner to write a piece for a special women’s issue, who wound up writing about Quinn’s murder. But fearing legal ramifications, Esquire decided not to publish the article. Thus, Rossner decided to fictionalize the case and expand it into a novel instead. And so, Looking for Mr. Goodbar hit the stands in June, 1975. A combination of a play on the phrase, "Looking for Mr. Right," and a candy-wrapper left at the Quinn crime scene, The New York Times called the novel "a complex and chilling portrait of a woman's descent into hell ... full of insight and intelligence and illumination.” It immediately became a runaway best-seller and was soon optioned by Paramount Studios for a big screen adaptation.

In the novel, Rossner lets us know on page one that her protagonist and surrogate for Quinn, Theresa Dunn, was dead, murdered by some creep she picked up in a bar when a one-night stand went bad. The rest of the novel is then spent showing us the tragic circumstances that led Theresa to this predicament: a sad tale of a double-life -- school teacher by day Theresa, and trolling the bars at night for rough-sex Terry; both of whom are crippled by an extreme case of self-loathing, which leaves her embroiled in a self-destructive, futile search for love, acceptance, or fulfillment on any level that will never, or, from what we’ve read, could ever, be satisfied.

In that New York Times review (June 8, 1975), critic Carol Eisen Rinzler states, “The question the author asks, as she tours the life of Theresa Dunn is, ‘What's a nice girl like you doing in a place like this?’” And to get to the bottom of this question, Rossner has us follow Theresa “through a miserable ugly-duckling-with-a-swan-for-a-sister childhood, a childhood also clouded with a crippling illness that leaves deep emotion and physical scars. She [then] meticulously explores and examines an adulthood of disastrous love affairs. And the answer that emerges --’Just unlucky, I guess’-- speaks to a larger question: how much control do women have over their own lives?

“Certainly, Theresa is unlucky,” Rinzler continues. “Her first lover, a professor who quotes Ecclesiastes to her as he ditches her after four incredibly exploitative years, is one of the best-drawn bastards of modern fiction. Having looked passively to a man and entirely past herself to make herself whole, the message Theresa takes away from the affair is that she's not good enough to hold a man. Her life becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy; she involves herself with a series of men -- married, newly divorced -- whose rejection is almost guaranteed.

“Finally, she is left looking for a life in which no rejection is possible; all she asks of men is that they want to use her body. Her life-style -- going to bars, picking up men and bringing them home to sleep with -- has the appearance of aggressiveness and the illusion of control. After all, she is the one who decides whom she'll sleep with, isn't she? She is in charge of her emotions, isn't she? But the author makes it clear that Theresa's life is one of consummate passivity and emotional impotence … This illusory control is [then] threatened when a decent and sensitive man falls in love with her. [This] love terrifies her; she sees returning it and committing herself to him as an abdication of her control, when what it really is, the author implies, is a chance for her to achieve control. But any action is beyond Theresa. Finally, temporarily estranged from her possible escape, Theresa goes to a bar and picks up her last man. Committing the ultimate passive act, she gets herself killed.”

Yeah, if you’ve read the book, or even just seen the movie version of Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), while watching La ragazza dal pigiama giallo -- released internationally as The Pyjama Girl Case -- unfold, it doesn’t take long to see a strong correlation to the Quinn case, too -- or more specifically, Rossner’s version of it in her novel. Here, Glenda Blythe (di Lazzaro) appears to be trapped in the same psychological quagmire, and her trio of lovers mirror Theresa Dunn’s almost identically; first off is her college professor, Henry Douglas (Ferrer), who shines her along and then brushes her off; second is Roy Connor (Rosini), an aggressive and possessive macho prick who's only interested in his end of the screwing; and lastly, Antonio Attolini (Placido), a simple but earnest beau, who truly worships and loves Glenda and begs her to leave her past behind and marry him.

In Rossner’s novel, Theresa, feeling she doesn’t deserve it, refuses the proposal; but in Mogherini’s film we take a slightly divergent course when Glenda takes the plunge after finding out she’s pregnant. And even though he isn’t sure if the baby was his -- he's not that naive, a slightly bitter Antonio doesn’t welch and still agrees to the wedding. And for a brief moment, Glenda appears to be happy -- or at least content. But this is short-lived when their baby dies not long after it was born. Depressed and disillusioned, saddled to a low-wage husband with no real prospects, and her marriage barreling toward a dead end before it even had a chance to begin, it’s no real surprise, then, when Glenda starts sleeping around again.

But when this proves to be another futile gesture to fill a bottomless hole, the girl realizes that the only person who treated her right and that she truly, maybe, cared for, was an old friend who lent her a pair of yellow silk pajamas at an impromptu sleep-over to wait out a violent thunderstorm. And since this is a gialli, you’d be right in thinking that friend was female; and though they shared the same bed that fateful night, come the dawn, Glenda wasn’t prepared for the lesbian advances at the time and quickly shied away.

Now, rejected and dejected, fraying around the edges of sanity, with nothing left to lose, Glenda burns all her bridges, steals Connor’s RV, and sets out to track down this old friend. And is this mystery friend our Pyjama Girl? Well, we’re going to have to wait for that answer as things continue to take a downward spiral for Glenda when she prostitutes herself for gas money, agreeing to a roadside-quickie with two slovenly travelers while one of their idiot offspring watches. Then, to complicate matters even further, Connor, thinking Glenda’s dumped him to permanently shack-up with Professor Douglas, rounds up his good friend Antonio and goads him into bringing his unfaithful whore of a wife back -- his words, not mine, whether she wants to or not.

Together, they track her down to a secluded spot where she had pulled the RV over to sleep for the night. And at Connor’s insistence, Antonio goes to retrieve her alone. When she refuses to comply, clad in those very same silk pajamas, things go quickly from tense to ugly to homicidal.

It should probably be noted that on top of the novel, a feature film, and this unofficial cash-in, the Quinn case also earned itself a Made for TV movie -- Trackdown: Finding the Goodbar Killer (1983), which focused on the NYPD’s efforts to track down Quinn’s killer, John Wayne Wilson.

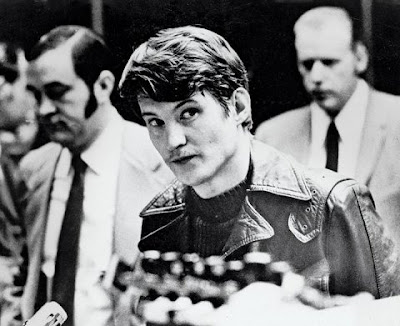

Wilson was a 23-year old drifter and hustler, who was hiding out in New York at the time of the murder due to a warrant for his arrest down in Florida. He first met Geary Guest, a 42-year old advertising executive, around 1970, somewhere amongst the smut shops and porno theaters along Times Square, where they exchanged money for sex. During the subsequent years before the murder, the two men struck up a friendship and would often go cruising or bar-hopping together. And on New Years Day, 1973, on a whim, they went to Tweed’s bar, where they ran into Roseann Quinn.

Quinn and Wilson, who introduced himself as Charlie Smith, kinda hit it off as the evening wore on -- other regulars would remember Wilson as being “tall, blonde, and handsome,'' and Guest bowed out early, heading home around 10pm. Quinn, Wilson, and several others then left Tweed’s around 1am and moved to another bar, The Copper Hatch. And at some point before closing time, Quinn and Wilson left that bar together, walked across the street, and entered her apartment building, where Wilson later stated they smoked some weed and made out, which led to an attempt to have sex. And I say “an attempt to have sex” because, apparently, Wilson was too drunk to perform. He would later claim Quinn then derisively insulted him over this cocksmanship failure, which pissed him off, which in turn led to an argument and request that he leave immediately. But things only escalated from there, whose aftermath ultimately resulted in what I described earlier.

After the deed was done, Wilson covered the body, took a shower to wash away the blood, got dressed, and then took the dead woman’s slip and wiped down the knife and her apartment, removing any fingerprints -- he even wiped down the elevator buttons once he reached the lobby. He then went to Guest’s apartment, looking for money to skip town, where he apparently confessed to the murder. Unsure if his friend was being serious or not, Guest gave him the money and Wilson fled to Springfield, Illinois, where he hid out at his brother’s house.

Thus, when Quinn’s body was discovered two days later, the police didn’t have very many clues to follow up on. But a massive canvasing effort did turn up several leads as the bartenders and patrons who knew Quinn also remembered the stranger who was with her; and one particular barfly, who drew sketches for people if they bought him a drink, remembered drawing two such pictures for Charlie Smith that night -- one of Mickey Mouse, the other of Donald Duck.

That put “Smith” in the apartment, and a composite sketch of the suspect soon followed. When Guest saw this sketch in the papers he freaked out, thinking it kinda looked like him as witness recollections kind of meshed the two men together. Unsure of what to do, and fearing he was an accessory to murder after the fact, Guest contacted his lawyer, who quickly cut an immunity deal pending his full cooperation with a Manhattan Assistant District Attorney. Guest, who had been in contact with Wilson over the phone since he’d left New York, confirmed the suspect was still hiding out at his brother’s house in Illinois.

When detectives arrived the following morning, Wilson simply asked for permission to put on his shoes before surrendering. He was arrested for the murder of Quinn, extradited back to New York, where he confessed, but it never went to trial as Wilson committed suicide by hanging himself while in custody on May 5, 1973. And in one last morbid twist, apparently, Wilson was on a suicide watch after he’d threatened to kill himself, which led to an argument with a prison guard, who taunted him, and then later threw several sheets into his cell to “help him on his way.” An investigation was held over these egregious circumstances but no charges were ever filed.

Of course, for his climax, Mogherini doesn’t bring in a complete stranger to be his killer. In fact, we’re still not really sure who the original victim was as all of these influences kinda collide into one big mind-f@ck of a twist. Yeah, the first time I watched The Pyjama Girl Case it took me until about halfway through the movie before I realized what Mogherini was up to. And what he was up to was pretty darned clever, and he executed it -- well, almost brilliantly, with only a few minor hiccups as things oozed toward that climax.

Basically, he breaks the story down into two progressive threads; the first deals with Thompson and Ramsey as they try to identify the corpse and catch the killer, while the other deals with forlorn Glenda and all her lovers. And nope, I didn’t realize until the scene at the seedy hotel when Glenda makes her break that half the plot so far had been nothing but one long flashback.

E'yup, as Thompson doggedly digs up clues in the other plot thread, that leads him closer and closer to the killer, crossing paths with surly Connor and flaky Antonio -- but never Glenda -- do we realize, as our heart sinks, that Glenda was the Pyjama Girl all along, she’s already dead, and not the killer’s next intended victim. And it would've been a kick-ass final shock/reveal, too, but Mogherini shows his hand -- in this case, those yellow pajamas, a little too early. And to complicate matters further, the movie then drags on for another twenty minutes to wrap-up all the other loose ends to one of the bleakest and most depressing films I’ve seen in a good long while as, once again, everyone we've met so far either winds up dead or incarcerated.

Still, Mogherini wound these two separate plot threads together rather beautifully into that final knot, leaving all kinds of clues for us to figure it out along the way -- and upon a second viewing it all seemed embarrassingly obvious, making one wonder if no trick was intended and I just missed something or things got lost in translation, again. Either way, though he kinda got his finger stuck in the tangle at the end, the director should be commended for his efforts.

Known mostly for his lavish production and set designs on minimal budgets for Mario Camerini -- Ulysses (1954), Pietro Francisci -- Attila (1954), Hercules (1958), and Mario Bava -- Danger: Diabolik (1968), Mogherini does the exact opposite here, using the monolithic and sterile concrete, steel and glass structures of Sydney to help emphasize the isolation and desperation of the characters -- outcasts all. And as his actors move around these sparsely populated streets, and Riz Ortolani's pulsating, John Carpenter-esque score hammers at you, you'd swear you were watching some kind of Dystopian sci-fi thriller along the lines of Soylent Green (1973) or Logan's Run (1976), not an Italian whodunit.

And then there's that totally obnoxious theme song crooned by Amanda Lear, who sounds like a morphine addicted and nicotine-scarred lounge lizard. Laughable at first, but dang it, if that doesn't bore into your head like a Ceti-eel and gets comfortable after a while -- and you'll wind up humming it to yourself, too, over and over again, for at least the next three weeks after the initial infection; trust me.

But! The Pyjama Girl Case is not without its flaws, especially in the investigation thread -- though most of them can be glossed over thanks in most part to the efforts of Ray Milland. It does the heart good to see the aging actor having a total blast with his character after so many years of angrily cashing-in-a-check in a string of low-budget, exploitative dreck -- looking at you, Terror in the Wax Museum (1973), Mayday at 40,000 Feet! (1976), and The Uncanny (1977).

Mogherini does do better with the Glenda thread -- in fact, I think he does a much better job of capturing the true nature of Rossner's character from the novel than Richard Brooks' official adaptation of Looking for Mr. Goodbar -- which Rossner apparently despised. For while Brooks does everything he can to eliminate Theresa's culpability in her own demise, to garner her more sympathy, Mogherini leaves it all in, making it hard to sympathize or even like Glenda -- likewise Theresa in the novel. One minute you want to give her a consoling hug, the next you want to gently bop her in the head to knock some sense into it.

Known mostly for her role as the rejected monster's mate in Andy Warhol's Flesh for Frankenstein (1973), the drop-dead gorgeous Dalila Di Lazzaro seems about as wrong a choice for the character as Diane Keaton was in Brooks' adaptation, but she anchors the film with a rock-solid performance as the doomed Glenda, bringing Rossner's novel back to it's true, self-destructive and tragic roots; and not, as Joe Bob Briggs put it in his book, Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History, “A defensive-driving course for women looking for sex -- a morality play, and if you don't pay attention and obey the rules, you could die at any moment.”

In the end, it may seem that who really killed Glenda doesn't matter. She knew what she was doing, knew it was wrong, and still made a lot of bad choices, usually making things worse. And that is one of the biggest problems most people have with The Pyjama Girl Case. Yes, she dug her own grave, but did Glenda or Linda or Roseann or Theresa really deserve to die because of these mistakes? I mean, Are we still blaming the victim, here?

Originally posted on January 12, 2008, at 3B Theater.

The Pyjama Girl Case (1978) Zodiac Produzioni :: Producciones Internacionales Cinematográficas Asociadas (PICASA) / P: Giorgio Salvioni / AP: John Taylor / D: Flavio Mogherini / W: Flavio Mogherini, Rafael Sánchez Campoy / C: Carlo Carlini / E: Adriano Tagliavia / M: Riz Ortolani / S: Ray Milland, Dalila Di Lazzaro, Michele Placido, Howard Ross, Ramiro Oliveros, Mel Ferrer