At a small ocean-side greasy-spoon well off the beaten path on Route 101, the owner of this eatery barely ekes out a living.

Minimally staffed by a world-weary waitress and a cantankerous short-order cook, what few customers George (Wynn) does get consists of an occasional long haul trucker and the staff of a government research facility nestled somewhere in the hills up the road a piece.

And, well, wherever they come from, all of these scant customers can agree on two things: one, they'd all like a fling with the saucy Kotty, and two, Slob's cooking is awful. But the thick-headed Slob (Marvin) couldn't care less what others think, and Kotty (Moore) turns them all down flat.

See, she's currently attached and swapping-spit with one of those research scientists; a Professor Sam Baniston (Lovejoy), who's also trying to help her ditch this dead-end occupation and shepherd her into a cushier government job by coaching her through the Civil Service exam.

Thus, as we meet a few more kooky denizens of this diner, including a daffy salesmen named Eddie (Bissell), and a shifty-eyed fishermen, Perch (Lesser), things seem normal enough on the surface, but underneath something far more sinister is happening once the sun goes down and the kitchen closes for the night.

Seems

over the past few weeks several of those government researchers have up

and disappeared without a trace; and they were all last seen eating at

this very establishment.

And not only that, but there are other transactions going on at the diner. Transactions that are off the menu and take place strictly under the table.

And what are these clandestine transactions all about? Secrets. Secrets bought and sold that could bring about the end of the world as we know it...

The New York Times (June 20, 1953).

In August of 1950, after the FBI ferreted out their spy ring, a Federal grand jury indicted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on 11 counts of conspiracy and espionage for allegedly passing on the secrets of the A-Bomb to the Soviets.

Later convicted on these charges in March, 1951, despite the couple's protests of innocence, the Rosenberg's, admitted Communists, were sentenced to death for this act of treason; a sentence that was eventually carried out in June, 1953. But this was not the end of it. No. Far from it.

History would show this notorious incident of espionage only added fuel to Senator Joe McCarthy's Stomp-A-Commie-Crusade; and Hollywood, already stinging from the whipping it took from the House Un-American Activities hearings in 1947, which resulted in the Black List, where countless artists and craftsmen suddenly became persona non grata to the studios, were eager to make nice with a series of Anti-Communist films:

The Red Menace (1949) and I Married a Communist (alias The Woman on Pier 13, 1949), which purported the menace was already here; I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951), a tale of union busting; Big Jim McClain (1952), which featured John Wayne rooting out Communist sympathizers; and assorted scare shorts like What is Communism? (1952), which exposes their insidious agenda step by step; and Red Nightmare (1957), where Jack Kelly gets a harsh lesson in skewed civics as he is content to let others worry about the Commie menace at our doorstep only to awaken one morning to life in a gulag.

These were the most overt examples that I could think of -- the total evangelical whackadoodlery of Estus Pirkle and Ron Ormand's If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do (1971) came later. But all were in an effort to bolster the perception of Tinsel Town's unwavering patriotism to avert any more governmental grievances.

There were more subtle (-- but not THAT subtle --) entries into this new genre with the likes of The Whip Hand (1951), Red Snow (1952), and The Steel Fist (1952); and Elia Kazan, after naming names, justified his actions with Man on a Tightrope (1953), where even the circus wasn’t immune to Communism, and On the Waterfront (1954), which championed the informer as the hero of the piece in a crusade to stamp out corruption.

Even second tier studios like Allied Artists got in on the act; and Edward Dein’s Shack Out on 101 (1955) is a prime example of this type of output.

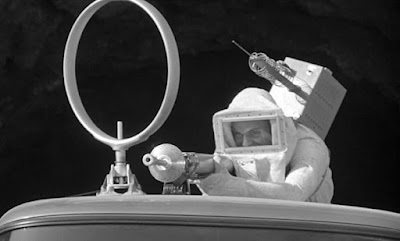

An Atomo-Paranoia-Sleaze-Noir, the separate ingredients of Patriotism and Red Scares in Shack out on 101 are clearly definable to your viewing palate as the film digests, but these morsels are essentially overwhelmed by a few more spicier ingredients thrown in with the best of intentions to make it all go down a little easier.

For, not only did the married filmmaking tandem of Edward and Mildred Dein throw the kitchen sink into this seamy little potboiler but added the stove, the fridge, the cupboards, and all the above's contents into the mix as they tried to subvert this central theme under several layers of steamy romantic intrigue, oddball characters, and laugh-out-loud comedy.

Strangely, each element on its own works fairly well but kinda curdles when baked together. Sticking with the culinary metaphor, admittedly, the end results taste kinda funny. Not bad, mind you. Just funny -- a bit off, maybe -- with each bite either too salty or too sweet or too bland that never reaches any sort of satisfying equilibrium. (Note to self: You are so talking out of your "You Don't Even like to Cook" ass right now.) Anyways...

Yeah, the soapy melodrama just never jives properly with the cloak and dagger stuff. The comedic elements work best, especially a few throwaway bits with George and Slob working out, and the resulting pissing contest over whose legs are in better shape -- a contest Kotty eventually has the last word on; and George and Eddie swapping fish tales and testing out some new fishing equipment.

Frankly, the whole plot feels like a hyper-condensed season of your garden variety soap opera, where said soap latches onto the latest headlines or hot-topic and folds it into one of its many subplots.

Here, the viewer is plopped down right into the middle of it, beginning with Slob's initial molestation of Kotty on the beach, whose tired reaction says this kinda crap happens all the time, and who only gets indignant when the grab-fanny cook spoils her latest batch of laundry.

Now, with a soap, you would have months and months to work this story-line -- hell, in some cases, years; here, we barely have an hour as a frustrated Kotty moves from man to man, looking and longing for love or some kind of stability, eventually sniffing out the nefarious truth behind Bastion and Slob's secret sea-shell swapping sessions down by the sea shore but doesn't quite grasp the stakes until it is far too late.

For, unlike the Rosenbergs, here, not only are those Commie bastards stealing classified information from the research center through several stooges, they're actually kidnapping scientists and engineers and smuggling them out of the country through Mexico, destination Moscow, to unlock more Atomic secrets for Uncle Nikita.

Discovering her beau (and ticket out of this shack) is one of these stoolies, in perhaps not the wisest of moves, knowing they've killed several people already, Kotty's self-righteous, snit-fueled tirade nearly gets everyone else killed, too, as the mysterious Mr. Gregory, the man behind this nest of vipers, finally reveals himself, who decides it's time to cut bait on this operation and leave all the witnesses at the bottom of the Pacific.

The Grand Island Independent (April 16, 1957).

Now, since everything that brought us to this point, and the climax itself, to the pat happy ending, is all carried out about six-and-a-half miles somewhere above “over the top” an argument could be made that Shack Out on 101 should be considered a farce, which kinda makes sense, making it a nice subversive foil for this particular genre that was already fizzling out.

And despite all these complaints and snarky observations, I'm happy to report that the cast overachieves and makes all of these disjointed plot elements work.

As the Tomato, whom everyone wants to *ahem* “sample,” Terry Moore is a million miles away from her big screen break as the young ingénue in Mighty Joe Young (1949). She brings a solid “been there, done that, screw the lousy t-shirt” weariness to Kotty, who once more sees a way out of this funk only to have the door seemingly slammed in her face.

The constantly blustering Keenan Wynn is great, too, as always, and plays well off the bumbling Bissell. But Lee Marvin steals the movie as the slovenly Slob, who isn't as slovenly and thick-headed as he lets on.

It also helps that the film itself looks fantastic. Credit to cinematographer Floyd Crosby, who used the limited sets brilliantly, keeping things nice and dingy and sleazy, and who used the cramped and limited space in the diner to his advantage by having the camera ridiculously close to the action at all times, resulting in a seedy documentary feel that's about [--this--] close to crossing the threshold of cinéma vérité. Seriously. You can almost smell some Pine Sol wafting from the toilets and hear the grease popping on the griddle.

This would be one of Crosby's last stops before he hooked up with Roger Corman and the boys from American International Pictures, starting with Fast and the Furious (1954), and whose skills are kinda underappreciated in the success of both.

Floyd Crosby.

One also cannot discount the efforts of editor George White, who also stitched together the similar docu-noir, The Phenix City Story (1955), and the noir to end all noir, The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946). And then there’s the music of Paul Dunlop, whose horn-heavy spazz-jazz riffs only amp up the proceedings even more.

After finishing Shack Out on 101, the Deins latched onto the wrong bandwagon with Calypso Joe (1957) -- yup, there was a time when most people predicted calypso music would have more staying power than rock ‘n’ roll.

But then the couple were roped in by

Universal and scripted the strangest, but surprisingly effective entry

in that studio's resurgent monster movie movement with Curse of the

Undead (1959), which throws a vampire into a western, making him an

indestructible hired gun set loose on a range war. You wouldn't think

that would work but, believe me, it does.

Thus, despite its haphazard structure and kitchen-sink narrative, Shack Out on 101 will surprise you when it's over and done. It shouldn't work either, but it does.

Apparently, the film's original title was Shack Up on 101 but some muckety-muck at the studio didn't like the euphemistic connotation of "shack up" (-- some sources claim the objection came from Moore), and so producer Mort Millman made the change.

Whatever the title, more folks probably need to see this gritty and dirty and highly idiosyncratic thriller.

Originally published on June 18, 2019, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

Shack Out on 101 (1955) Allied Artists / EP: William F. Broidy / P Mort Millman / D: Edward Dein / W: Edward Dein, Mildred Dein / C: Floyd Crosby / E: George White / M: Paul Dunlap / S: Terry Moore, Frank Lovejoy, Keenan Wynn, Lee Marvin, Whit Bissell, Len Lesser, Frank De Kova

%201955.jpg)

%201955_61.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

%201955_16.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

%201955_25.jpg)

.jpg)

%201955_10.jpg)

%201955.jpg)

%201959.jpg)

%201955.jpg)