Our featured feature opens somewhere near the open mountain ranges of central Illinois (-- well, at least we never see any palm trees), where the camera slowly tracks, following the noise of a boisterous ballad bellowing out of a car radio, until it settles on a couple of teenagers parked in this secluded lover's lane.

Thus and lo, as these two lovebirds break a Cardinal B-movie Sin by engaging in some passionate, premarital necking, lost in the heat of all those post-pubescent hormones, this mutual groping continues until they’re distracted by a strange noise coming from outside the car.

Here, they pause long enough to look out, around, then up; and then they both scream as some horrible, unseen menace looms large over them that’s immediately cut-off as the screen fades to black!

When the wrecked car is later found covered in blood, the authorities find no other trace of the former occupants -- he typed ominously. Trying to find the owner, the car's registration leads the State Police to nearby Ludlow, where they make an even more startling discovery: the entire town has been leveled to the ground! And after searching through the wreckage, no survivors are found; and stranger still, just like with the car, there are no bodies to be recovered here either -- he typed even more ominously.

This level of a catastrophe proves a little too weird for local law enforcement, who quickly defer to the Illinois National Guard, which is brought in to investigate what appears to be some kind of preternatural natural disaster. They set-up camp in the neighboring town of Paxton. From there, they cordon off what's left of Ludlow until some answers can be found as to what exactly happened to all of its 150 residents.

Enter intrepid reporter Audrey Aimes, stage left -- well, make that highway left. On her way to cover a different story for the National Wire Service, Aimes (Castle), a former Korean War correspondent, becomes intrigued when she can’t get any straight answers as to what lies beyond the extensive military roadblock between her and her original destination.

And while her attempt to sneak by and have a look for herself gives the reporter an answer as to “What” happened to Ludlow, the “Why” is still anybody’s guess as Aimes is caught snooping and her camera confiscated by a passing patrol.

Next, she heads into Paxton, where the reporter is stonewalled further by the operation’s commanding officer, Colonel Tom Sturgeon (Henry), who will neither confirm nor deny anything as he interviews a few potential witnesses. But they only provide more questions than answers. And the only thing determined is that whatever happened to Ludlow happened between the hours of midnight and 4am.

Undaunted, and playing on a hunch, Aimes calls her editor to see if there are any atomic installations in the area. (Remember, this is the 1950s we’re talking about and radiation took the brunt of the blame for damned near everything.) But the only thing even remotely close to what she's suggesting is a Department of Agriculture experimental research lab.

It's probably a dead-end, she thinks, but the tenacious Aimes investigates her only lead. Here, while visiting the lab, she meets our square-jaw, Dr. Ed Wainwright (Graves), and his partner, Dr. Frank Johnson (Wyenn), who has been rendered deaf and mute by an accidental dose of radiation because of … reasons.

Obviously, judging by the embarrassing floor show that follows, these two don't get many visitors; but they do go on to explain how their experiments involve the use of radiation to speed up the photosynthesis process, resulting in giant mutations. (Tomatoes the size of basketballs, strawberries the size of soft balls etc.) And while not yet ready for human consumption, they hope to rectify that in the near future.

Though impressed with their massive end-results, Aimes is curiously concerned about any possible radioactive side-effects. But Wainwright assures they've had no problems -- well, except for some bugs, especially some locusts, who kept eating their experiments. (Not sure why he gleaned over what happened to his partner. That's me shrugging right now.)

Oh, and then there was that little problem with the storage bins for their mutated grain: it seems they inexplicably collapsed and all of their contents disappeared without a trace under mysterious circumstances -- but I'm sure it's nothing. They’re with the government. And they’re here to help. *sheesh*

Returning to Paxton, after promising to hold her story until the mystery is resolved, Aimes is finally allowed to go into Ludlow proper under escort to document the scene with her liberated camera. She is shocked by what she sees: the town is beyond devastated; it's been completely torn asunder and flattened.

Putting two and two together, the reporter decides to visit those destroyed grain bins for a little compare and contrast. (Dang she’s good.) Going back to the institute for directions, the doctors decide to tag along.

Well, turns out those storage bins were in even worse shape than Ludlow. And while Wainwright and Aimes get to know one another, giving Wainwright time to explain that his partner is the botanist while he's an entomologist, working in tandem to improve the food supply, poor Dr. Johnson soon discovers what’s been causing all the trouble -- and then promptly gets eaten by it at the same time!

For it seems that after eating all of that irradiated grain, Dr. Wainwright's harmless locusts weren't quite so harmless after all…

After nearly ten years of congressional hearings, lawsuits, counter-suits, rulings, non-compliance, token efforts, and judicial review, on May 3, 1948, the United States Supreme Court, in a 7 to 1 decision, decided the five major Hollywood movie studios -- Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO, plus the three minor studios -- Columbia, Universal International, and United Artists, were in violation of the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act and issued the Paramount Decree, which toppled the oligopoly of the Hollywood Eight.

Before this landmark decision, the studios made the films, distributed the films, and exhibited the films on an exclusive basis in their own select theater chains, which they owned and operated; and once these new releases played out there first run engagements, these now not-so-new releases would then move onto the larger, independently own theater chains, who paid exorbitant fees for the films and then split box-office profits with the studio.

Third Run Showcase '44. (The Independent, February, 1944.)

The independents were also forced to block-book the studio’s entire slate of films, usually sight unseen, getting stuck with the box-office misses just to have a chance at the hits. And then, finally, these wrung-out films would trickle down to the smaller, individually owned theaters, who also had to pay these same fees and faced the same strong-arm studio tactics, essentially forcing them to try and eke out a living on concession sales alone.

Thus, by 1945, while those eight studios owned only 17-percent of the theaters, they received 45-percent of the box-office revenue. Which is why, back in 1940, the US District Court decided this was an unfair practice and handed down a consent decree; a settlement, which would limit block-booking to only five films and incorporated timely trade shows that provided screenings so independent exhibitors could choose what they wanted and were no longer forced to blind buy “bad” films.

The Grand Island Independent (November, 1958).

Obviously, that didn’t stick as the studios essentially ignored the decree in favor of their own Unity Plan, implemented in 1943, which, of course, was in violation of the settlement. Thus, the lawsuit resumed, and over the next five years it would battle its way to the Supreme Court, who officially broke the old studio system in half, separating the production and the exhibition of films permanently, forcing the Hollywood 8 to diverge and sell off their theater chains in order to even the playing field.

All well and good in theory, but this effort sort of back-fired due to some unexpected and exacerbated circumstances. First off, ticket revenues were already on the decline and were only getting worse thanks to the infestation of television. And secondly, with this further reduction of revenue after losing their theaters, studios started to cut back on productions even further, which caused an even bigger issue.

“The major [studios] began to produce fewer features every year,” said Kevin Heffernan (Ghouls, Gimmicks, and Gold: Horror Films and the American Movie Business 1953-1968, 2004), and more of these films were expensive blockbusters showcasing [new] technology such as widescreen, stereo sound, and color. Production [had fallen] steadily from 479 features in 1940 to 379 in 1950 to 271 in 1955, and finally reaching an all time low of 224 in 1959.

“This product shortage hit the smaller neighborhood theaters particularly hard," Heffernan continued. “The unavailability of first-run product combined with the studios’ practice of ‘bunching’ major releases together in late summer and holiday seasons meant that many smaller theaters, and even some larger circuits, would face a chronic shortage of product for much of the year … A steady supply of product was critical to these theaters: even a marginal or unsuccessful box-office performance kept the doors of the theater open and enabled the snack bar to help finance the operation’s mortgage and payroll.”

The Grand Island Independent (June, 1953).

Thus, as studios leaned into short-term gimmicks like 3D StereoScopic pictures like House of Wax (1953) or the epoch change to wider screens and CinemaScope “super productions” like The Robe (1953) to win audiences back, forcing theater owners to spend a lot of money to convert their venues to adapt or die, critic Bosley Crowther noted in The New York Times Magazine (June 14, 1953) how this appeared to be an attempt to “garner the bulk of the movie revenue from a limited number of annual productions released to a few thousand -- or perhaps one fourth -- of the nation’s theaters. Where this would leave the other theaters, No one knows.”

Thus, by 1956, while testifying before the Senate sub-committee on Small Businesses, Harry Brandt, then president of the Independent Theater Owners of America association, painted a rather bleak picture, saying, “We buy all the companies. We need all of the product that is made. Particularly the small neighborhood theater. These small neighborhood theaters, particularly (those) in double feature areas, of which there are 5200, are reported to be in the red … 95-percent of those must (show) a double feature (with a) three-times-a-week change. That means they need six pictures a week. That means they need 312 pictures a year. If the industry is producing 270 at the present time, obviously there isn’t enough to go around.”

The Grand Island Independent (December, 1953).

But as the old axiom goes: When one door closes, another door opens. And this vacuum was a golden opportunity for independent producers and productions, who no longer had to fear the stranglehold the Hollywood 8 once held, squeezing them out by holding exhibitors hostage to their normal extortion practices.

Poverty Row bottom-bill fillers like Republic, Monogram and PRC did their best to fill this gap. Under the stewardship of Steve Broidy and Walter Mirisch, Monogram, wanting to shake their low-rent B-Movie reputation, would rebrand itself as Allied Artists in 1952, started spending a little more on productions, and ushered in an era of what Mirisch referred to as “B+ pictures.” Even Hollywood stars like Kirk Douglas, Gregory Peck, and Burt Lancaster broke away from studio contracts, went freelance, formed their own production companies, and started producing their own features.

Meanwhile, James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff defied the odds of the tumultuous and economically uncertain times by forming the American Releasing Corporation in 1954 with the release of Roger Corman’s The Fast and the Furious (1954). Two years later they rebranded, too, as American International Pictures; and by embracing the new film-going majority of teenage audiences -- along with some savvy marketing campaigns, AIP soon morphed from brash upstart to major minor to a minor major in the Hollywood food chain.

But! While Allied Artists and American International found their feet, exhibitors were still struggling to find reliable streams of product to exhibit. Said Heffernan, “The situation became so acute that soon there were periodic calls across the industry for exhibitors to finance the production of features.”

The Los Angeles Times (September 23, 1962).

This was nothing new but the successes were rare. As Robert L. Lippert later reminisced to Art Ryon (The Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1962), "Every theater owner thinks he can make pictures better than the ones they send him. The trouble with big studios is that they’re monarchies. It’s all in the family. Each big studio used to make about 52 pictures a year. Now they spend all their money on eight big ones.”

Lippert owned and operated 139 theaters and drive-ins in Northern California, Oregon and Arizona. In 1946, tired of paying “exorbitant” rental fees, he formed Screen Guild Productions, which later became Lippert Pictures. Most of their output was dirt-cheap westerns and genre pictures -- Rocket Ship X-M (1950), Lost Continent (1951), Project Moonbase (1953), but Lippert started finding mainstream success backing Samuel Fuller’s I Shot Jesse James (1948), The Baron of Arizona (1950) and The Steel Helmet (1951).

Lippert was also the first to sign a major deal with Hammer Productions in England, which netted him Spaceways (1953) and The Creeping Unknown (alias The Quatermass Xperiment, 1955), which opened the door for their redefining horror revival with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). He then signed a lucrative production deal with 20th Century Fox to provide second features in their new CinemaScope process for the newly formed Regal Pictures (-- in Regalscope), which resulted in genre stalwarts like Kronos (1957), The Fly (1958), Space Master X-7 (1958) and The Alligator People (1959). Said Lippert, “The word around Hollywood is: [Lippert] makes a lot of cheap pictures, but he’s never made a stinker.”

Meanwhile, back east, theater entrepreneur Joseph E. Levine had been producing films since 1945 and did reasonably well thanks to his brazen advertising campaigns; as another film axiom goes: “Sell it, don’t smell it.” But Levine struck gold in the 1950s when he started importing foreign films. In 1956, he acquired the Australian film, Walk into Paradise (1956), which drew poorly. But then Levine retitled it as Walk into Hell and soon had lines around the block.

Said Philip K.Scheuer (The Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1959), “Mr. Levine has gotten rich by operating on the principle of the floating crap game. He glommed onto a picture no other distributor wanted, had hundreds of prints made, moved into a town with saturation bookings and full-page ads and was on his way to the next burg before his bemused customers knew what struck them.”

That same year, Levine secured co-distribution rights to the Japanese film Gojira (1954) for $12,000, rebranded it as Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956), spent another $400,000 on a marketing blitz, and earned over $1-million at the box-office. He pulled the same stunt with the Italian film Attila (alias Attila, il flagello di Dio, 1954); $100,000 upfront and $600,000 in promotions, which netted $2-million. He then doubled-down on Hercules (alias Le Fatiche di Ercole, 1958): $120,000 for the rights and dubbing, $1.25-million on advertising, and a distribution deal with Warners, resulting in 4.7-million dollars worth of tickets sold. Needless to say, Levine and his Embassy Pictures were well on their way.

But, again, these kinds of successes were rare. In 1954, a group of theater owners under the Allied States Organization umbrella announced they had agreed to terms with producer Hal Makelim to finance a feature a month for 12 months for their 2,500 theaters. But this quickly fizzled as Makelim only managed two features -- The Peacemaker (1956) and Valerie (1957) before the plug was pulled. And down in Texas, radio-man Gordon McLendon managed to produce the two-punch combo of The Giant Gila Monster (1959) and The Killer Shrews (1959). These were released regionally through his Tri-State theater chain to modest returns. They even managed to gain some national distribution through American International, but McLendon would only produce two more films.

There were others, of course, who had various degrees of regional and national success -- the Woolner brothers, Jack H. Harris and K. Gordon Murray to name a few. And it was under these very same trying circumstances that a certain giant-bug movie came into existence. Some would even call it, quite possibly, the beginning of the end of theater exhibition as we knew it. Well, more like the end of the end's beginning of the beginning. Let me explain.

See, back in 1953, the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) merged with United Paramount Theaters Inc., which took over Paramount’s orphaned theater chain after the Supreme Court ruling in ‘48. And in September of 1956, they announced the formation of their own movie studio -- AB-PT Pictures Corporation, to provide sustenance for their starving theaters. Said Irving Levin, the newly appointed production chief of the newly anointed studio (The Motion Picture Herald, May 10, 1957), “Shortage of product is the basic reason for going into production and we anticipate making good quality product.”

AB-PT then struck a deal with Republic Studios for the use of their production facilities and distribution hubs; and in January of 1957, the studio announced a goal of producing six films that first year, with the hope of expanding to 20 features in the near future. And to hedge their gamble, AB-PT would initially focus on producing low-budget genre double features, which had become quite popular with teen audiences thanks to AIP, Allied Artists and Howco International -- another conglomeration of theater owners out of South Carolina, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi, led by J. Francis White and Joy Houck, who also got in on the production game, specializing in drive-in fare -- Carnival Rock (1957), The Brain from Planet Arous (1957), My World Dies Screaming (alias Terror in the Haunted House, 1958).

As Scheuer wrote (The Los Angeles Times, December 3, 1956), “AB-PT is probably playing it safe with this subject and should cash in -- if anything is sure these days -- on the Sci-Fi craze. It’s ultimate importance, however, will be measured by its ability to lead, not follow.” And first out of the gate for AB-PT was an atomic-paranoia / giant bug invasion shocker, Beginning of the End (1957); and to write, produce and direct this inaugural effort, they turned to Bert I. Gordon.

The pride of Kenosha, Wisconsin, Bert Ira Gordon came into this world as of September of 1922. And by the age of just six, his love of movies was already firmly entrenched. Said Gordon in his autobiography (The Amazing Colossal World of Mr. B.I.G., 2010), “My Saturdays and Sundays were mostly spent in a movie theater. My mother would drop me off at ten in the morning, and then pick me up in time for supper. I never tired of watching them over and over again: the double features, the serials, and the short comedies that ran before the movies.”

As this love affair with illuminated celluloid continued, the young Gordon became friends with the theater manager of his favorite childhood haunt, who let him hang around backstage whenever a vaudeville troupe or live-act passed through, learning the secrets and sleight-of-hand of the magicians, ogling the dancing girls, and absorbing the tricks of the promoters / hucksters and their trade. “For a boy of seven or eight watching it all, my love of ‘show-biz’ and my desire to be a part of it was enhanced,” said Gordon. “I was fascinated by the magician’s illusions -- illusions that deceived the senses and challenged the intellect of the audience, by appearing to be one thing when it was, in fact, another. The seed was planted: someday, I would create my own magic.”

As to how Gordon would implement that dream, the answer came from a different part of the theater: the projection booth, where he also had free run. “I enjoyed seeing how the operation of a movie theater worked,” said Gordon. “Watching the projectionist do his thing, keeping his two projectors threaded-up with the 2000-foot reels of the feature movie, switching from one projector to another when the film on the reel reached its end, and then threading up a fresh reel of film to be ready for the next projector switch-over.”

Bert I. Gordon -- alias Mr. B.I.G.

As he shadowed the projectionist, he was soon promoted to an unofficial assistant, where he was allowed to stitch the film back together if it ever snagged, snapped, or got caught and melted. Then, one fateful night, the projector jammed badly, resulting in the excision of about a foot of film that had been “chewed up” too badly to be usable.

Here, young Gordon retrieved the mangled piece of film from the trash can, took it home, and carefully cut out the salvageable frames. He then fashioned a homemade projector out of a shoebox and a flashlight, and arranged his first film exhibition. “I held a slideshow for my parents, whom I trapped into watching my minute-long presentation.”

The Grand Island Independent (August, 1957).

This passion was further kindled when Gordon was gifted a 16mm movie camera by his aunt for his ninth birthday. Said Gordon, “The moment I picked up the camera, I started to make movies and I never stopped.” And while making his early short films with friends and family, the novice filmmaker had already started experimenting with optical tricks in-camera, including kit-bashed split-screens and ghosting in images through filters and double exposures.

After enrolling at the University of Wisconsin, where he was sort of a one man newsreel team, with the United States’ entry into World War II in 1941, Gordon dropped out and joined the Army Air Corps. And while stationed in California, he met Florence “Flora” Lang, who was attending the University of Southern California, where she was studying film production.

The St. Louis Dispatch (April 17, 1960).

The two would marry in June, 1945, and when the war ended, the couple moved to Flora’s hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, where the couple started a family (-- they had three daughters, Carol, Susan and Patricia), and opened an advertising agency, shooting and producing television commercials for local businesses and a short nature documentary for Outdoor Magazine.

But the itch to do something bigger, to make a movie, soon had Gordon selling off the business and packing up his family for a move to Hollywood. But the transition from commercials to movies was not easy. According to Flora in the Beginning of the End DVD commentary (Hen’s Tooth Video, 2010), Gordon had been promised a job in California before making the move; but by the time they arrived, it was too late and the job had been given to “somebody’s nephew.”

From there, Gordon found it nearly impossible to just get through a studio’s front door. And on the rare occasion when he did get a meeting with a producer, they all encouraged him to go back to Minnesota and echoed what Lippert said: the only way to successfully break into Hollywood, they told him, was if Darryl Zanuck or Sam Goldwyn was your father (-- or be someone's nephew). Beyond that, forget it.

But Gordon was determined to make it, and despite not being a member of any trade union, he did pick up a few gigs here and there working in television as a freelance news cameraman or production assistant; though it would seem the minute he latched onto something, the show would be canceled -- Cowboy G-Man (1952), Racket Squad (1951-1953). He was also hired by a TV producer to take 26 imported B-films and whittle them down to fit a half-hour syndicated time slot. Said Gordon, “The films were made in England that truthfully weren’t exactly the best England had to offer, so cutting them down to 25-minutes, leaving five minutes for commercials, improved the films quite a bit.”

Then, fate stepped in when Gordon was hired by a film processing lab to shoot some needed 16mm inserts. And when he visited their offices, Gordon just so happened to bring his trusty 16mm camera with him and was spotted by Al Zimbalist, there for unrelated purposes, who asked Gordon if he would like to make a movie with him?

Zimbalist had worked in the publicity departments for Warner Bros. and RKO in the 1930s and ‘40s before signing on as an assistant for producer Edward J. Alperson on a series of gender-swapped tales of adventure -- The Sword of Monte Cristo (1951), Rose of Cimarron (1952); and then did the same for Walter Wanger on another feminized revisionist take on The Lady in the Iron Mask (1952).

Then, Zimbalist decided to strike out on his own around 1952, announcing the formation of Motion Picture Artists Corporation; and sticking with the theme, the fledgling producer’s first proposed feature was originally supposed to be Miss Robin Crusoe (1953). But this was put on hold to focus on a couple of Sci-Fi Creature Features shot in 3D first -- the notorious Cat-Women of the Moon (1953), and the even more notorious, Robot Monster (1953).

The film Zimbalist and Gordon would do together was Serpent Island (1954), a high seas adventure yarn of hidden treasure and voodoo cults starring the not-quite gone-to-seed Sonny Tufts. Zimbalist financed the film’s $18,000 budget via a deferment loan from Consolidated Film Labs. And while Tom Gries would write and direct the film, Gordon basically handled everything else -- serving as the producer, cinematographer, and editor.

Zimbalist and Gordon would team up again for King Dinosaur (1955), where a quartet of astronauts land on an Earth-like planet inhabited by dinosaurs. Complications ensue. Both onscreen and off. Here, Gordon co-wrote the script with Gries based on Gordon’s Beast from Outer Space story idea. He would also direct the picture and, with an assist from Flora, provide the special-effects.

To pull off those needed dinosaurs, Gordon decided to do as much of the VFX as he could in-camera without any opticals to help keep costs down. And with an assist from animal wrangler Ralph Helfer, who would handle all kinds of “giant-sized” critters on a ton of Gordon’s future films, they used an iguana, a caiman, and a salamander (I think) as their dinosaur surrogates. Using macro-lenses, these reptiles were shot at high speed as they rampaged across minimal miniature sets; or they were shot against a blue screen to be matted in or run through a rear-projector later to give the illusion that they were giants.

However, his “stars” were reluctant to cooperate. As Gordon later explained to Mark Thomas McGee (Fast and Furious, The Story of American International Pictures, 1984), “You never know when an animal is going to move. I shot thousands of feet of film and the sons of bitches would not move and nothing would make them angry. So I finally ended up in a library and found a book with a chapter on iguanas that said they needed extreme heat to be active. So I bought a couple heaters and blew hot air on them with fans.”

And for whatever he couldn’t pull off, Gordon would liberally borrow footage from Hal Roach’s One Million B.C. (1940). Strangely enough, instead of using the footage of the decked-out caiman and monitor lizard from that film, locked forever in eternal combat, savaged and ravaged, that would haunt many ‘a’ more low-budget feature yet to come, Gordon decided to basically restage it with his Iguana-Rex fighting another caiman instead, then the salamander. The results of these unreasonable facsimiles were … passable, but not great. But they were good enough to get picked up by Lippert, who sent it out in 1955 to not great (but better than you’d think) box-office results and a universal panning by the critics.

But Gordon was philosophical about the end results. “Of course these first two films weren’t what anyone would consider works of art or superior productions, and they were made for practically non-existent budgets. Sure, they’ve been fair game for movie critics, and anyone who thinks he’s one. But, taken in the context in which they were produced, these two movies were courageous upstarts of young careers. Something to be proud of.”

Now, as the legend goes, during the film’s limited pre-production, Gordon test-screened some stop-motion dinosaur footage presented personally by Ray Harryhausen -- hot off the commercial success of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953). And as the legend continues, at the end of the screening, Gordon did not comment at all and just walked out.

Obviously, an upset Harryhausen didn’t appreciate the cold shoulder, and he didn't get the job, either, and later broke the bad news to his friend, Ray Bradbury. (But don’t feel too bad for Harryhausen. His consolation prize was It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), starting a long and fruitful collaboration with producer Charles Schneer.) Later, after attending the world premier of King Dinosaur, an incredulous and spiteful Bradbury confronted Gordon in the lobby and scolded him over his fatal choice on the VFX, saying the film wouldn’t make a dime.

And for Gordon, it didn’t. As he had done previously to Phil Tucker after the completion of Robot Monster, Zimbalist took the two films and ran, taking all of the profits with him. (For the whole sad and sordid Robot Monster affair and its aftermath, we covered it over at the old bloggo.) But despite this set-back, with two feature films under his belt, Gordon was ready to tackle another. Only this time, he would practically do everything himself -- at least according to him.

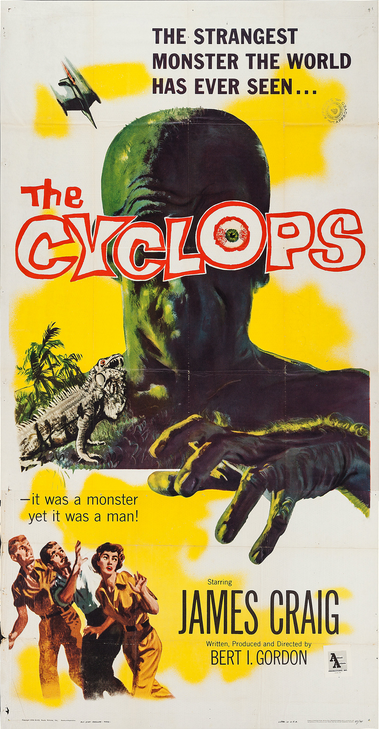

To finance The Cyclops (1957), Gordon got a Beverly Hills lawyer to put up $100,000 for this tale of a woman latching onto a uranium expedition down in Mexico, where her fiance had disappeared three years prior. What they find instead are super-sized irradiated animals and a mono-optical giant, who turns out to be exactly who we all thought it would be.

Starring James Craig, Tom Drake and genre stalwarts Lon Chaney Jr. and Gloria Talbott, with some memorable make-up effects by Jack Young, The Cyclops proved to be a sleeper hit. Box Office Magazine wrote, “For its praiseworthy qualities, most of the credit for The Cyclops is due Bert I. Gordon, who wrote, produced and directed, as well as master-minded the special photography and technical effects, which, along with good performances, result in the feature being a standout in its field.”

The Buffalo News (October 30, 1957).

Said Gordon, “The finished feature played well, and I made a distribution deal with RKO with a cash pickup (advance) that put the film into profit before it even appeared in a theater. The investing lawyer got his money back plus a profit.” Before the film was released, the moribund RKO finally declared bankruptcy and the film was sold off to Allied Artists, which delayed its release to 1957. But perhaps even more importantly than making a profit, having written and directed The Cyclops, Gordon was accepted into the Writers Guild (WGA) and the Directors Guild (DGA). He’d made it. It was official. He was in.

And with his bona fides firmly established, Gordon was next approached by Irv Levin at a dinner party, who asked if he would be interested in making another genre film for the newly formed AB-PT. According to Flora, who witnessed the occasion, her husband was eager and Levin said to come up with an idea and he’d be in touch. Not missing a beat, Gordon took a table napkin and a pen and quickly scribbled down some notes about a swarm of giant grasshoppers attacking Chicago. Levin loved the idea, and, according to Variety (November 30, 1956), AB-PT officially announced Beginning of the End would be their inaugural feature, with production set to commence in December, 1956.

Now, while Gordon originated the idea, the script was completed by Fred Freidberger, who had scripted The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, with an assist from Lester Gorn -- his only screen credit. The plot they concocted doesn’t stray too far from the George Worthing Yates model, firmly established with THEM! (1954) -- a strange, inexplicable occurrence, procedural efforts to discover the root cause, and once that’s resolved it turns into a race against the clock to stop this discovery from starting an extinction level event.

There’s also a touch of H.G. Wells’ 1904 novel, The Food of the Gods and How it Came to Earth, where a scientist devises a special feed that allows plants and animals to grow to an abnormal size -- notions Gordon would borrow again for Village of the Giants (1965) before making an “official” adaptation with H.G. Wells’ The Food of the Gods (1976). Notions that had recently shown up in Universal International’s Tarantula (1955), too, where another scientist’s good intended experiments in irradiated animal feed go staggeringly awry, resulting in a giant arachnid laying waste to half of Arizona.

Here, like the gargantuan ants spawned in the fallout of White Sands in THEM! and Professor Deemer’s supplemental nutrients in Tarantula, Beginning of the End’s Dr. Wainwright subs in radiation for Bensington and Redwood’s toxic alkaloids of Herakleophorbia IV; and who, like the others, wasn’t prepared for the possible side-effects of his experiments in gigantism until it was too late and they, essentially, reared up and bit him in the ass -- well, almost, as he and Aimes leave Johnson to his grisly fate, barely escape the deadly swarm of mutated locusts, and flee back to Paxton.

Unfortunately, their outlandish claims of giant killer grasshoppers are understandably met with much skepticism from Col. Sturgeon. Luckily, through persistence, the survivors do manage to convince him to at least investigate the wrecked storage site. Thus, Sturgeon assigns Captain Barton (Seay), along with a squad of infantry, to accompany him and Wainwright back to the scene of this alleged attack.

Upon reaching the site, they find no trace of Dr. Johnson (-- explaining what happened to all those other victims, having been consumed completely). Then, as the squad fans out and heads into the surrounding trees, all seems quiet -- too quiet, but not for long!

For suddenly, from out of nowhere, the mutant locusts start screeching at deafening levels, who then swarm en masse and attack! And so, the crack rifle squad, which thought it was on an ersatz snipe-hunt just moments before, now finds themselves in a deadly firefight.

Hopelessly outnumbered and on the verge of being overwhelmed and wiped-out, the few survivors beat a hasty ‘strategic withdrawal’ back to Paxton for reinforcements. And while Sturgeon quickly mobilizes his entire National Guard unit for the pending Battle of Paxton, Wainwright tries to warn him that there are too many locusts and they won’t stand a chance unless the regular army is called in. Seems he can tell by the volume of chirping that the swarm has to be, well, ginormous, and it will take a lot more firepower than Sturgeon can muster locally to stop them.

To accomplish that, we get an obligatory trip to Washington DC, where Wainwright and Aimes plead their case in front of a committee run by General John Hanson (Ankrum). But once again, the gathered military brass and advisors are dubious and don't fully understand or grasp the magnitude of the threat until they receive word that Paxton has been overrun and destroyed by the locust swarm. (And since we never see him again, it's safe to assume Sturgeon was among the "thousands" of reported casualties.)

With that, Hanson takes command and appoints Wainwright as his special scientific advisor on giant mutant bugs and how to properly squash them. (It’s his mess after all. Only right that he should be responsible for cleaning it up.) However, they did catch one lucky break: the mutation to giant size short-circuited something on a genetic level, leaving the insects’ wings stunted and unusable, meaning these locusts can’t fly like their normal brethren.

But even though the army is mobilized and engages the grounded enemy with everything they've got -- troops, tanks, artillery, and napalm -- they have little effect in slowing the swarm down: Pontiac, Peoria and Joliet are all overrun as the locusts circle ever closer to the rapidly evacuating Chicago. Insecticides and smoke don’t have any effect either; and after a rousing battle sequence between the infantry and a tank battalion against the giants, the locusts breach the defensive perimeter and are soon pouring into the Windy City's suburbs unabated.

Thus, with no other alternative, General Hanson gets authorization to use an atomic bomb to neutralize the threat. Thinking that action is a little too drastic, at least at this juncture, Wainwright, with a little help from Aimes, hits upon the idea of reproducing the insect’s mating call -- and then use this signal to lure them all into Lake Michigan to drown. All he needs is an oscillator, some copper wire, a loud speaker -- and one live giant grasshopper!

Here, Hanson provides him everything he needs -- including a captured bug, caught while dormant under the cooler overnight temperatures, but won’t postpone the bomb drop, leaving them only a few precious hours to try and mimic that mating call.

And so, while Wainwright tinkers with the oscillator, Barton breaks another Cardinal B-movie Sin by waxing nostalgic about life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; and then we really glean he’s a walking piece of bug-chow when he mentions his wife and kids for no real reason, and how he can’t wait to get back to them once all of this is over.

Thus and lo, it's no real surprise, then, when Wainwright finally hits upon the right frequency that it causes the captured locust to go berserk, break containment, and kill the poor sap.

Despite this tragedy, with the experiment a success, the A-bomb drop is successfully aborted in time. (And the sharp eye will spot Kirk Alyn, the original live-action Superman, piloting the plane. Also, sharp ears will easily recognize the voice of Paul Frees dubbing over the pilot of a scout helicopter.) But, by now, the locusts are so spread-out over the city they must lure them to Wainwright's lab first, and then into the lake.

Thus, the plan must be executed in two stages. And while Wainwright and Aimes remain at the lab for Phase One, Hanson takes up a position out on the water with more sound equipment for Phase Two. And with a nod to Aimes, who flips the switch, Phase One commences as the mating call signal is broadcast all over the city, driving the giant locusts into a frenzy. Then, behold, as the locust swarm stampedes over several scenic postcards of Chicago, rampaging toward Wainwright’s lab:

Thus and so, closer and closer the giant locusts come, in an orgiastic frenzy as they scale the photo of the target Wrigley Building. And things start to get a little hairy when the lab tucked inside is about to be swarmed under before the broadcast signal is switched at the last second to Hanson’s boat out on Lake Michigan.

With that, still in the grips of a sexually-charged hysteria, the locusts withdraw, head further east, along the Chicago River, and plow into the lake, where they dry-hump each other until the mutations all drown -- much to Hanson’s relief and Wainwright’s delight.

Friends, Videophiles, and my fellow B-movie Brethren, lend me your ears and traveling mattes. For I have come not to bury Bert I. Gordon, who passed away recently in March, 2023, at the ripe old age of 100, but to praise him -- well, to praise his feature film efforts. (And we’ll be explaining that small caveat of separating the art from the artists as we go from here.)

Now, over the years, as I’ve encountered them, I’ve always enjoyed Gordon’s films on many levels but also came to truly appreciate them simply for what they were and, perhaps more importantly, for what they weren’t. What they have is an old pulp magazine flare. No frills, acceptable VFX given the budgets and the era in which they were made, and a straight-forward narrative that barrels toward the climax as if its pants were on fire. And what they didn’t have, is a lot of padding, nonsensical stock footage abuse, or the usual bait-n-switch one inevitably finds in these types of micro-budgeted genre films.

One of the banes of the low-budget exploitation film’s existence has always been that it’s cheaper to tell than it was to show, leading to reel-killing speeches and plot dumps, where we heard about what we could be watching instead of actually watching it.

This, to me, is what always separated and elevated Gordon’s efforts from the rest of the dreck as he, despite the budget restraints, never fell into that trap. No. The man and his productions always made an earnest (and sometimes spectacular) effort to deliver what the trailer and poster art had promised -- no matter how cheap and shoddy those efforts were.

“The great thing about Bert I. Gordon was that he was fearless,” said McGee. “Most low budget filmmakers never thought about tackling spectacle. It was too time consuming. Too expensive. Special effects in most B-pictures of the time consisted of a puff of smoke, whatever you could hang from a wire, and maybe a double exposure. Not Bert. He would try anything.” And I don’t think any film in Gordon’s overcompensating oeuvre represented this attitude better than Beginning of the End.

Sure, after the initial skirmish at the grain bins, there are moments when all we get about the ongoing locust onslaught are just the ‘after action’ news reports over the radio as Illinois is overrun and its population masticated into morsels off screen. But Gordon was holding his cards, sand-bagging the audience before he unleashed all kinds of hell for the Battle of Chicago:

It’s one helluva showstopper, and it truly is one of my favorite Creature Feature moments to come out of the 1950s. And while some would call the efforts hair-brained, half-assed, cheap and shoddy, I wouldn't necessarily beg to differ. I totally get it. But! If you’d stop giggling and take a closer look, the Devil, as they say, is in the Details.

In 1956, Australia was in the grips of being overrun and devastated by a locust invasion, a swarm of some 400-square miles in size, resulting in millions in property damage and lost crops. The United States had also suffered through several plagues of locusts on a biblical scale, usually coinciding with successive years of drought like back in 1874 and more recently when they exacerbated the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, leading to starvation and a mass exodus from the Great Plains.

Often described as a “metabolic wildfire,” the grasshoppers would consume everything they landed on that was edible; and not only crops but fabrics, leather, paint, varnish, and even the processed wood they covered, stripping everything bare. Of course with Gordon, bigger was always better. If a swarm of tiny insects could do that much damage, imagine what kind of havoc a swarm of giant locusts could wreak?

Once again, the use of any kind of stop-motion animation to pull the critters off was quickly ruled out due to budget constraints. As was the use of any kind of giant, go-motion mock-ups like Gordon Douglas had used so effectively in THEM!. And so, Bert I. Gordon would once again use his in-camera tricks of split screens, static mattes, and rear projection to shoot small for big. Here, he ran into a bit of a problem: the local California grasshoppers proved too small and wouldn’t hold the camera’s focus. He would need something bigger.

(Editor's note: after researching, and chasing our tail on the exact differences for hours, we realize grasshoppers and locusts are technically not the same thing, in a square / rectangle sense, but we’ve decided not to get too pedantic over the difference and hope you won’t either and we'll gladly concede you are the smartest person in the room. Congratulations.)

“Strangely enough, the stars of Beginning of the End are 600 Texas Grasshoppers,” said Ann Jones (Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 23, 1957). “Six hundred Luber (sic) grasshoppers were captured in Texas by the Department of Agriculture and shipped in specially constructed cages to Hollywood. It was necessary to clear the shipment through federal, state, county and city authorities before the dangerous insects could be brought into California.”

The species chosen was the Romalea microptera, or eastern Lubber, which was native to the southeast and south central United States, and was well known for its size and bright coloration. (One of its many aliases is the Georgia Thumper. And in Mexico they’re known as the Negra Diablos -- the Black Devils.) These brightly colored insects were chosen because they grew up to 2.5 to 3 inches in length, and their stunted wings kept them grounded, leaving them to crawl around or hop, which, apparently, they weren’t very good at. They also have several defense mechanisms, including a loud “hiss” to frighten off predators and the emission of a “foul-smelling and foul-tasting foamy secretion from its thorax” whenever it’s disturbed that wasn’t exploited in the film.

Now, those numbers Jones quoted were probably an exaggeration by the AB-PT publicity department. In my research, I’ve found import tallies ranging from 300 to 400 to 1,000 grasshoppers but I believe the actual tally was nearer to 200. What she didn’t exaggerate were the bureaucratic hoops the production had to go through to get the invasive species to California -- and more specifically, Gordon’s garage, where he filmed most of his miniature VFX shots.

“I could only import males because they didn’t want the things to start breeding,” Gordon confided to McGee. And so, before they were shipped from Waco, Texas, someone had to sex all 200 Lubbers. And when they arrived in California, to assure no ecological disaster was forthcoming, the insects were sex-checked again, just to be sure. Then, on top of all that, a representative of the USDA had to take a daily headcount to make sure none had escaped. And when filming wrapped, in theory, they would be deported and shipped back to Texas (-- or more than likely, destroyed).

But as shooting commenced, that headcount started to drop precipitously. Apparently, the grasshoppers didn’t adapt well to their cramped quarters and weren’t really taken care of properly, causing them to turn cannibalistic -- less than two-thirds survived the trip. And between that, and the attrition of being blown up or immolated by the miniature pyrotechnics during the combat scenes, when it came time to film the climax there were only about a dozen grasshoppers left. (And call me crazy, but it sure looks like Gordon subbed in a mass of red crickets for that long shot of the beach scene.) And when the VFX inserts were finally completed, only three Lubbers were left standing. Fate unknown.

One of Gordon’s ‘technical innovations’ while making King Dinosaur was to eschew the cost of building elaborate miniature sets and to just use enlarged still photographs of a needed background as backdrops for his lizards to crawl over instead. For the Battle of Chicago, after all that effort for the earlier stages of the fight, Gordon really leaned into this technique for the invasion of Chicago proper as the grasshoppers raced by photos of city landmarks or crawled over several cut-outs.

For the Wrigley Building assault, the photo was placed on the ground for the insects to scale, prodded along by the forced hot air from several hair-dryers. It should also be noted that at least some effort was made to make these photographs topographical -- three-dimensional, to give them some depth. When the bugs were “shot and killed” in the movie, the photo mock-up was tilted up and someone would tap on the opposite side until the targeted grasshopper fell away to its doom -- or crawled off the building and into the ether. Allegedly.

Now, I think the notoriety of this infamous gaffe might have originated with author Stephen King. Forgive my faulty memory, but I recall either reading about him smoking some reefer and watching Beginning of the End and laughing his ass off in reference to this error -- most probably in Danse Macabre, his treatise on modern horror; or it was one of his characters doing the same thing in a novel -- most likely in IT, where he talks about one of the grasshoppers crawling off the building into thin air. But did this gaffe really happen?

For due diligence, I have watched this film dozens of times and I’ve scoured the footage again, but I’m damned if I can pinpoint this exact incident. (One of the grasshoppers does crawl off the top of the screen but he was technically still on the building.) So, was this all just based on a faulty memory of King’s? And others, embellished over time? It could’ve still happened, I guess; and a best educated guess would be King watched an improperly matted broadcast or VHS version that wasn’t cropped properly in the right aspect ratio, which led to the stray, gravity defying menace that, technically, wasn’t meant to be seen.

Tampa Bay Times (July 19, 1957).

Regardless, this cheapjack VFX tactic is what usually draws the venom of critics and outright laughter from general audiences, which was made even worse by the mishandling of the ballyhoo in the build-up and release of the film that promised “New and Groundbreaking Techniques” that would “for the First Time Ever deliver Live, Giant-sized Carnivorous Creatures Attacking People and Demolishing Cities.”

“Beginning of the End was a critical dart board and of no help was the promotion that did not exploit the locusts authentically,” lamented D. Earl Worth (Sleaze Creatures, an Illustrated Guide to Obscure Hollywood Horror Movies, 1995). “In the trailer, they could hardly be seen at all. Some ads used the sloppily designed silhouette of only one locust. Others had toothy big-eyed terrors almost identical to the caricature-like monsters in the posters from THEM!. This was supposedly the ‘first’ film with ‘Real-Live Creatures’ -- a false revelation cleverly described as ‘Newmendous!’”

Charlotte Observer (July 17, 1957).

I freely admit the bits using over-sized stills and hot-air prodded grasshoppers in Beginning of the End are both tacky and kinda terrible. But as impressive as the giant mock-ups were in the far superior THEM!, this film just vibrates with some kind of strange frisson when you watch the lightning quick, superimposed locusts swarming all over the screen, closing in for the kill -- an atavistic reaction to things that creep and crawl. And one should appreciate the time and effort it took to layer all of that footage together -- and the fact that there was neither time nor money to fix or fine tune anything.

Here, let's take a closer look at the scene where the patrol is first attacked by the giant locusts near the grain bins to help you all get what I am trying to sell. In that first frame, one can easily see the natural matte line as the locust first comes into view. In the second, though not perfectly executed, I love the effort to bring one of the legs “over” the line.

For most productions, that would’ve been enough. But Gordon then takes it a step further in frames three and four by matting in another locust in the foreground, which quickly skitters through the frame, giving the illusion that it's in-between the two soldiers as the one nearest to us retreats off camera, giving us four total layers of action.

Gordon didn’t have to do all that. But he did. As to how he did it, I’ll let the man himself (try to) explain it: “Depending upon what the script required the giant grasshoppers to do, we either filmed them against a blue screen or a miniature set,” said Gordon. “The former process entailed the making of holdback mattes on the optical printer, which gave us an exact duplicate of the grasshopper footage shot against the blue with the use of filters, which resulted in the grasshoppers appearing as a solid black image.

“Then, by combining that footage of the solid black holdback mattes, with the principal photography of the people, we had perfectly clear areas in the shape of the locusts chasing our cast, or whatever, when the film was developed. Then, running the footage through the optical printer again, along with the footage of the grasshoppers we had filmed against the blue screen, using a filter to filter out the blue, the grasshoppers filled in their images into the clear places the black matte had created.” Clear as mud? Great!

Of course, Gordon fails to mention how he used the same process shots over and over and over again. Or how in some instances the grasshoppers weren’t matted properly and their legs ghosted into the ground. And there are moments, too, due to their dark eyes and color spots, the matting process would glitch and parts of these menaces would become transparent -- a glitch that would plague a lot of Gordon’s output.

Still, despite the gaffes, the efforts do leave quite the impression -- good or bad, depending upon the willing suspension of disbelief of the audience, helped immensely by the deafening levels of the amplified screeches and the constant cutaways to a close-up of the monster’s mandibles.

To help fill in the gaps between the giant bug attacks, the production lucked out on the cast. Despite prominent roles in Stalag 17 (1953) and The Night of the Hunter (1955), Peter Graves was mostly relegated to second or third banana in a string of studio B-Pictures like Fort Defiance (1951) and Black Tuesday (1954). But as that work dried up he eventually made a successful transition to television -- most notably in Fury (1955-1960) and Mission: Impossible (1967-1973).

He was also no stranger to Sci-Fi pictures, having already starred in the highbrow Red Planet Mars (1952) and W. Lee Wilder’s low-brow and dirt-cheap Killers from Space (1954), along with delivering one of the greatest closing soliloquies of ever after defeating a hostile Venusian turnip for Roger Corman’s It Conquered the World (1956). And in Beginning of the End, Graves adds a lot of weight to the gobbledygook Gordon was selling. It also probably didn’t hurt that Graves’ older brother, James Arness, had appeared as the co-lead / giant-bug-fighter in THEM!.

As the story goes, Peggie Castle was discovered by a talent scout while eating in a Beverly Hills restaurant and was immediately signed to a seven-year contract with Universal-International, where she made her film debut in When a Girl's Beautiful (1947). Her biggest role was probably playing the deadly femme fatale, Charlotte Manning, in the steamy adaptation of Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury (1953), but she also appeared in Albert Zugsmith’s Red-baiting Invasion U.S.A. (1952) and a ton of westerns -- Wagons West (1952), The Yellow Tomahawk (1954), Overland Pacific (1954).

“I have been shot, stabbed, stuffed in a car trunk, and strangled. I once played a ghoul risen from the dead,” Castle recounted to Lucy Key Miller (Views and Profiles, Chicago Tribune, June 26, 1957). “In Beginning of the End I’m pursued through the deserted streets of Chicago by hordes of gigantic grasshoppers.”

Problems with alcohol would derail her career and kept Castle in the Bs. And like Graves, she would transition to television by 1959, landing a role on Lawman (1959-1962). Voted Miss Cheesecake and Miss Three Alarm, and rightfully so, Castle had beauty and brass and she brings both to Beginning of the End, making quite the impression despite being stuck in an otherwise thankless role.

The Grand Island Independent (August, 1957).

Now, Castle had won the role of Audrey Aimes over Mala Powers -- City Beneath the Sea (1953), The Colossus of New York (1958). Also under consideration was Patricia Dean, a “sexboat” discovery of the studio’s. A former dancer at the El Rancho Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada, Dean would still appear in the film. Twice. First in a brief scene as a Red Cross worker at the HQ in Paxton, and later as the girl wrapped in a towel that is menaced and eventually eaten (off-screen) by one of the locusts during the Battle of Chicago. Dean would also provide the cheesecake that’s prominently featured in the advertising materials for Beginning of the End.

Meanwhile, when I first saw Joe Dante’s Matinee (1993) in the theater, I was a little disappointed that I was the only one who laughed at the General Ankrum joke. In hindsight, I was proud to have gotten the reference. Morris Ankrum had been acting in films since the 1930s, but in the 1950s he always seemed to play the General (or a similar rank) in things ranging from Invaders from Mars (1953) to Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956) to The Giant Claw (1957) to Beginning of the End. And you always knew this shit would get sorted once General Ankrum showed up. Well played, Mr. Dante. Well played.

Behind the camera, Jack Marta was a veteran cinematographer, who had worked at Republic since Gene Autry’s Sagebrush Troubadour (1935). He mostly shot westerns for the likes of John Wayne before he broke big and Roy Rogers -- and one of my favorite takes on the Alamo with Frank Lloyd’s The Last Command (1955), meaning Beginning of the End was a definite change of pace. But Marta acquitted himself well, bringing a stark and crisp look to the proceedings and always kept the camera moving to keep audiences interested between the VFX set-pieces. (The Hen’s Tooth DVD looks amazing and really enhances his efforts.)

Editor Aaron Stell was another Republic western vet, but he had stretched his legs a bit stitching together Creature with the Atom Brain (1955) for Sam Katzman before making sense of the beginning, the middle and the end of Beginning of the End. After, he was all over the place, splicing things together on films ranging from Touch of Evil (1958) and To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) to Silent Running (1972) and Cornbread, Earl and Me (1975).

Also of note is art director Walter Keller, who had served with Val Lewton at RKO for his string of moody psychological thrillers, meaning he contributed to the look and feel of Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943), The Leopard Man (1943), The Seventh Victim (1943) and The Body Snatcher (1945). I love the mock-ups of the giant fruits and vegetables, making a lot out of a little. And the attention to detail on the props and the accuracy of the military uniforms -- the US Army's 33rd Infantry Division was the designated unit of the Illinois National Guard, and the US Fifth Army was headquartered in Chicago at the time -- helps sell it all, too.

Which brings us to Gordon’s secret weapon, who provided the glue that always held his pictures together, kept them focused, and moving forward: the scores of Albert Glasser. Glasser was a disciple of Dimitri Tiomkin, whose bombastic film scores had been nominated for over 20 Academy Awards, winning for High Noon (1952), The High and the Mighty (1955), and The Old Man and the Sea (1959); and frankly, he should’ve been nominated and won again for the eerie, theremin heavy score for The Thing from Another World (1951). But we’re here to talk about Glasser.

Albert Glasser (Image courtesy of Film Music Review.)

Glasser’s rousing, horn heavy, John Phillip Sousa-esque score for Beginning of the End is unrelenting as it pounds viewers into their seats and dares them to keep up. He had been working in the industry, mostly uncredited, since 1938 as a music copyist, an orchestrator, or writing additional music. His first credited score was for the PRC shocker, The Monster Maker (1944). From there, he bounced around the minors for Albert Zugsmith and Sigmund Neufeild. As to how he got on Gordon’s radar, as Glasser told Tom Weaver (Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes, 2000), “I met him after I finished Huk (1956). I was laying the tracks in with a film cutter. Suddenly, the door opens and Bert Gordon comes in and says, ‘Who wrote that stuff?’”

Apparently, Glasser and Gordon were working in the same building in nearby editing suites. Glasser was finishing up Huk and Gordon was in post-production on The Cyclops. He also loved what he’d overheard. “He was working next door finishing up a picture and was looking for a composer,” Glasser continued. “He wanted to hear more of my stuff and so he came over to the house. He said, ‘I want you! I’ve done two pictures so far but I’m not very happy with the music, it didn’t give me the life that I wanted. Your kind of stuff has BALLS!’ He paid me $4,000 for the whole thing, including the orchestra. I had fun with it -- it was a cute little picture, well done. From then on, I was his boy.”

The actual total budget of Beginning of the End is hard to source. According to a statement by then AB-PT President Leonard Goldenson back in 1957, the average cost of their pictures was $300,000 -- though odds were good that was another exaggeration to impress ticket buyers. In the commentary track, Flora remembered the budget as being around $150,000. Regardless, I believe every cent of that wound up on screen. In comparison, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms cost $400,000 and THEM! was budgeted at just under a million.

Principal photography for Beginning of the End began on December 6, 1956, which ran for two weeks. This was followed by another five weeks of post-production on the VFX and second unit work in Chicago for a few crowd scenes and some pick-ups and needed still photographs, which were shot in the early morning hours to make it look like the city had been evacuated. And aside from the military maneuvers, the only stock footage used is the aftermath of several tornadoes subbing in for the destruction of Ludlow.

Again, most of the VFX were shot in Gordon’s garage, be it herding the insects in front of a blue screen or having them crawl around on those photos. I will assume the rear-projection shots with the mustered army were filmed at Republic to be matted in later. The military roadblock and the opening sequence with the two teenagers was shot somewhere in the San Fernando Valley (-- explaining away the misplaced mountain range). Playing on the radio right before the first attack is Lou Partell’s “Natural, Natural Baby,” lulling the audience into a false sense of security, which was sent out as a promotional record by AB-PT to try and drum up ticket buyers.

As for the live action stuff, Gordon’s direction was serviceable. Not one for social commentary -- or romantic interludes, Gordon just wanted to tell a straight-up action / adventure story without any baggage. And as a field general on set, he sometimes came off as brash and a bit of a martinet, who had trouble connecting with his crew and cast -- especially the female members.

While making The Cyclops, Gloria Talbott and Gordon got off on the wrong foot when he questioned her ability to hold a scene with her male counterparts, and it only got worse from there according to her interview with Tom Weaver (Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes, 2000), “I was mad as hell that first day. I wanted to quit … He had a disregard for actresses, I do believe -- or maybe females in general. I just tried to stay away from Bert Gordon as much as I could. He just wasn’t a particularly pleasant person.”

Added Jacqueline Scott (Weaver, Science Fiction Confidential, 2002), who starred in Empire of the Ants (1977) for Gordon, “He would be very pleasant and very nice, and really never understood why anybody was upset at the end of the day. At the end of each day, he was just ready to get all cleaned up and have a nice dinner, and some people were ready to kill him. He was just in his own little world. There were trees and then there was water and then there were the actors, and there were tables and chairs, and it was all the same to Bert Gordon.”

And the testimonials kept on coming: “Unlike a lot of other low budget filmmakers, Gordon insisted upon the best special effects that he himself could assemble. He did a credible job with the modest budgets with which he worked,” noted Samuel Arkoff in his autobiography (Flying Through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants, 1992). But! Arkoff also mordantly told McGee, “He really took himself seriously, as though he was George Pal.”

Said American International’s monster-maker and prop man Paul Blaisdell (McGee), “Gordon was very demanding as a director. He also listed himself as the producer, the script writer, the special effects man, the optical effects man … There was THIS by Bert I. Gordon and THAT by Bert I. Gordon, on and on ad nauseam. And he was, as I said, rather impatient on the set."

Also chiming in was Duncan "Dean" Parkin. Parkin had played the one-eyed monster in The Cyclops, where he was nearly strangled to death by a 20-foot python named Consuela, and would later sub in as Glenn Manning post-face-plant off the Hoover Dam, replacing Glenn Langan, in War of the Colossal Beast (1958). But before that, he also pitched in on the VFX for Beginning of the End.

"I worked throughout the production on much of the special-effects ... right along with Bert, doing lots of the miniature and matte work, helping him set up shots, and actually maneuvering the grasshoppers," said Parkin (FIlmfax #58, October, 1996). As to why he didn't receive a screen credit for this, "All I can say is that it was typical of Bert not to credit others."

And Gordon was also not a friend of the ASPCA either, as the reptiles pitted against each other for King Dinosaur did not escape unscathed (-- in fact, I'm pretty sure that salamander didn't make it), and several mice were fed to the giant hawk onscreen during the making of The Cyclops; and I’ve read several accounts of both animals, insects, and arachnids expiring under the heat of the lighting needed to keep them in focus. And there are at least two instances in Beginning of the End where the Lubbers are doused in something and set on fire while they were still alive. Not to mention drowning what few were left by the end of shooting.

Gordon often referred to himself as Mr. B.I.G., a somewhat ironic play on both his initials and the subject matter of his films; and I say “ironic” because the guy measured in at five-foot five-inches. But if Gordon was the little tyrant king on set, Flora Gordon was the den mother.

Bert I. Gordon and June Kenney (The Spider, 1957.)

Said Talbott, “Gordon was like a man possessed because he did have to get it finished quickly; [The Cyclops] was all done in five or six days. But he certainly had it well organized -- and I’m sure that his wife had a hell of a lot to do with that. His wife was so sweet -- she was doing the script supervising, the wardrobe, making cookies, everything -- and he was so mean to her, like she was ‘the help.’”

Flora Gordon also had a dream of making movies. And from 1955 through 1976 she did just that by contributing in some capacity on her husband's films. She was in charge of the wardrobe on King Dinosaur and helped keep track of the continuity on the VFX shots to make sure everything was headed in the right direction to match the footage. She earned an assistant producer’s credit on The Cyclops while also handling the costumes, props, continuity, and, apparently, the catering.

Susan and Flora Gordon.

Flora would continue assisting with continuity and the VFX work for Beginning of the End and beyond. She was also instrumental in shepherding their daughter, Susan Gordon, into her acting career. Susan would appear in four of her parents films, including The Boy and the Pirates (1960), Tormented (1960) -- a film I love probably way more than it deserves, and Picture Mommy Dead (1966). She also appeared in The Man in the Net (1959) and The Five Pennies (1959), along with episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents ("Summer Shade," Season 6, Episode 15, 1961) and The Twilight Zone ("The Fugitive," Season 3, Episode 25, 1962).

Flora, meanwhile, would graduate to production coordinator on Picture Mommy Dead, and would serve in the same capacity on The Mad Bomber (1973) and The Food of the Gods, where she also served as an assistant director, earning her DGA card.

Alas, The Food of the Gods would also be the last picture Bert and Flora would work on together. And I honestly think you can sense her absence in Empire of the Ants and beyond. In an attempt to make her own mark, she broke away and struck out on her own, serving as a production coordinator and assistant director on Acapulco Gold (1976), Dogs (1977), and The Great Smokey Roadblock (1977).

Sadly, things fell apart from there on the personal side and the couple would divorce in 1979; and I fear it was rather acrimonious -- if I’m reading the tea leaves right. Gordon doesn’t mention Flora at all in his autobiography (-- a sloppy affair, but he at least talks about his children with her), but he barely refers to his second wife, Eva Marie Marklstorfer, whom he married in 1980, calling her the love of his life, and that was about it.

Meantime, changing her name back to Lang, Flora transitioned into television, where she settled in as a unit production coordinator on several TV movies -- Making of a Male Model (1983) and There Were Times, Dear (1985), as well as serving as the same for four seasons of Dynasty (1981-1989). Lang was also an original member of the newly formed DGA Women’s Committee and helped coordinate a study that showed of the 7,332 feature films made between 1949 and 1979 only 14 were directed by women, which led to a class-action lawsuit against several studios over discriminatory hiring practices. The lawsuits failed, but it was a step in the right direction.

Flora Lang-Gordon passed away in 2016 and it’s high time Mrs. B.I.G. gets recognized for her contributions, too. As Christopher Stewardson so eloquently put it (Dread Central, May 11, 2023), “It’s worth noting how much we owe Flora Lang in the creation of these pictures. She was essentially the special effects coordinator, keeping track of shot elements and continuity. And given that Gordon’s special-effects are arguably the most recognizable aspect of his filmography, Lang’s contributions are of considerable importance.”

The Chicago Tribune (June 19, 1957).

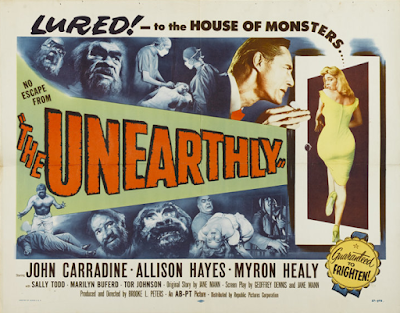

Beginning of the End would hold its world premier, appropriately enough, in Chicago at the Roosevelt Theater on June 19, 1957. Both Graves and Castle would attend, holding autograph sessions in the lobby. It was paired up with The Unearthly (1957) -- a throwback tale of mad science, the search for immortality, and glandular secretions.

It was an independently produced, five-day wonder courtesy of Brook L. Peters (alias Boris Petroff) with some spiffy production designs by Charles Hall, who had helped breathe life into the Universal classic Creature Features like Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Black Cat (1934) and, oddly enough, One Million B.C. And, really, aside from that and the cast -- John Carradine, Allison Hayes and Tor Johnson, there really isn’t much else there.

In desperate need of a second feature for their double-bill debut, AB-PT acquired The Unearthly after principal photography had been completed, which was a strong indicator on how well their film production experiment in making “quality product” was going.

Undaunted,

AB-PT unleashed their inaugural double-bill wide, giving it a

saturation booking in over 250 theaters in the Midwest and South during

its initial run before going into a nationwide general release through

Republic.

The Charlotte Observer (July 16, 1957).

Aside from that record, other special promotional materials included free tranquilizer pills and a first aid station in the lobby for those without the nerve to be “rocked out of your seat” or “shocked out of your skin.” In Florida, there was a $50 savings bond to be won for whomever submitted the best drawing of what the “real live creatures” would look like.(See below to find out who won.)

And while they took a critical drubbing, the double feature was an unqualified box-office success. But Variety quickly put things into perspective, saying, "Even taken on its own terms -- as a low-budget exploitation feature -- Beginning of the End hardly reflects the best effort of a major theater circuit … If AB-PT and its fellow theater-men regard this film as the answer to the product shortage, the motion picture industry might as well shut its doors this very moment."

The Tampa Bay Times (July 7 and July 17, 1957).

In the build up to the release of Beginning of the End, AB-PT had announced a whole slate of features to follow it up with. As Jones wrote, “Theater exhibitors in AB-PT have noted that box-office results indicate the primary movie audience is in the 16-to-25 age group. Although the company plans to produce films to suit all ages, they will especially stress movies for this age, as shown by some of the AB-PT pictures: Young Party Mother, Eighteen and Anxious, Ten Hours to Doom, Volcano Monster and Atomic Submarine. If, in a few months, the public shows it would prefer some musical comedies for a change, AB-PT probably will set its stars to singing, dancing and cracking jokes. Because, as the studio officials point out, AB-PT movies are made by showmen for showgoers.”

Looking over those five titles is a bit of a puzzler. The Atomic Submarine (1959) was two years away and wound up at Allied Artists. And Volcano Monsters makes one wonder if AB-PT had first crack at Godzilla Raids Again (alias Gojira no Gyakushū, 1955), Toho’s follow up to Godzilla, which was eventually released by Warner Bros., who changed the name from The Volcano Monsters to Gigantis the Fire Monster (1959). And all efforts to unearth anything on Young Party Mother and Ten Hours to Doom turned up bupkis, which leaves us with the curious case of Eighteen and Anxious.

In February of 1958, AB-PT released their second double bill of Eighteen and Anxious (1957) and Girl in the Woods (1957), a pair of melodramas, which would also turn out to be their last release, period, as the company suddenly ceased operations, spreading whatever films they had left in development to the winds. And with the loss of that revenue stream, Republic Pictures officially pulled the plug and shuttered-up in 1958, too.

And so, once again, a Bert I. Gordon feature proved the death knell to yet another storied Hollywood studio through no real fault of his own. But fear not, Gordon landed on his feet well enough and signed a four picture deal with American International. And he was already working on the production of The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) before Beginning of the End was even released, running off screenwriter Chuck Griffith, who didn’t appreciate Gordon dictating to him over his shoulder from behind. The Spider (alias Earth vs. the Spider, 1958), War of the Colossal Beast (1958), and Attack of the Puppet People (1958) would follow before Gordon filed a lawsuit, claiming AIP was skimming profits, before once again moving onto other pastures. (He would make a brief, triumphant return to AIP in the late 1970s.)

All told, Gordon made some 24 features in his decades long career, including two failed TV pilots -- Famous Ghost Stories (1961), which was technically and edited down version of Tormented, and Take Me to Your Leader (1964), and three sex farces -- How to Succeed with Sex (1970), Let’s Do It (1983), and The Big Bet (1987). If I had to pick a favorite, it’s a running dogfight between Beginning of the End and Village of the Giants, depending on where I’m feeling on the Totally Bonkers Scale when you ask. As for his best, well, I’d say The Magic Sword (1962).

As to what to make of his efforts as a whole, I heartily echo Gary Westfahl’s summary of Gordon’s cinematic contributions. Said Westfahl (The Biographical Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, 1999), “Accounts of Bert I. Gordon's career usually follow a standard line of invective: he was the infamous "Mr. B.I.G.," a penny-pinching schlockmeister who employed cheap rear projection to churn out inept science fiction and fantasy films, mostly iterative variations on the overused theme of fantastically enlarged beasts and men. These characterizations are not entirely baseless, and there are certainly a number of films in Gordon's filmography that richly deserve nothing but scorn.

“Yet Gordon also warrants more sympathetic consideration … For filmgoers of a certain age, Gordon's films were something to look forward to, and they were rarely disappointing. Further, while his early films were usually threadbare -- classic mom-and-pop operations, with Gordon and wife Flora Gordon chipping in for most of the off-screen labors -- they were not slapdash; within the confines of his circumstances, Gordon usually tried to do good work, and if blessed with capable performers and a decent story, he might succeed.” And succeed he did, more often than not.

Look, there’s a reason the Gordons hold the dubious record for the most features featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000 (1998-1999) -- King Dinosaur (S2, E10), The Amazing Colossal Man (S3, E9), Earth vs the Spider (S3, E13), War of the Colossal Beast (S3, E19), The Magic Sword (S4, E 11), Tormented (S4, E 14), Beginning of the End (S5, E17), Village of the Giants (S5, E23), and they’re some of my favorite episodes, too. They clearly are the best of the “worst” and should be celebrated as such. They are terrible, and awesome. Terribly awesome, and never boring, and a ton of fun.

If it’s been awhile since you’ve watched Beginning of the End, or have only seen it on VHS, I do recommend that 2010 disc from Hen Tooth’s Video -- though it’s now long out of print and kind of expensive.

The film is finally presented in the proper aspect ratio and looks gorgeous, though it appears to be missing certain elements -- most notably the scene where the troops flee from their first encounter with the grasshoppers, where a giant locust pursues the fleeing truck, which appears in the old Video Treasures VHS copies and the MST3k version. On the 2010 disc, the scene is cut short and quickly fades to black.

And sadly, the included commentary track with Flora Lang and Susan Gordon is a bit of a wash due to the moderator failing to coax many recollections or revelations from the fading memories of the commentators. (Flora was insistent that Beginning of the End was shot after The Amazing Colossal Man and Attack of the Puppet People.) So, fair warning, before you start shelling out any money.

Streaming