Not to belabor the obvious, but the following will make a whole lot more sense if you’ve read Part One of our Two Part series on film director Phil Karlson’s career first, from assistant directing on Destry Rides Again (1932) to directing our featured film Framed (1975), with the likes of Scandal Sheet (1952), The Phenix City Story (1955), The Silencers (1966), and Walking Tall (1973) logged in between.

Now, once you’re all caught up, you’ll remember when we last left the film that triggered this massive After Action Report, Ron Lewis, our unwitting protagonist, was caught up in a massive conspiracy and has been framed for the murder of a sheriff’s deputy, who brutally assaulted him, that was clearly a case of self-defense. As for why? Well, we’ll be unraveling this miscarriage of justice and the machinations behind it along with Lewis on his long road to revenge, beginning with his processing into the Tennessee State Penitentiary (playing itself).

Branded a cop-killer, the scornful prison guards aren’t all that friendly toward Lewis. And when they force the prisoner to strip and shower, armed with a mop handle (--again, I'm not gonna draw you all a picture), one guard accosts Lewis while he's still in the shower; but Lewis quickly gets the better of him.

Unfortunately for Lewis, the guard (West) gets his revenge after he's placed in his cell, where they proceed to apply tear gas, then mace, and then finish up by beating the living crap out of their trapped and helpless prisoner, completing some kind of macabre initiation ritual for the ‘fresh fish’.

As his sentence commences, Susan tries to visit Lewis, several times, but he always refuses to see her, thinking she ran out on him when he needed her most. But as weeks turn into months, and months into years, Lewis isn’t as alone as he thinks. Luckily, for his health, Lewis’ reputation as a high stakes gambler has drawn the attention of Sal Vicarronne (Marley).

Serving time on a petty bribery charge, the elderly Sal is a made man with the mob. He also owns most of the guards and runs several gambling and bookmaking operations inside the prison. In fact, Sal will tell you he has enough money socked away to buy the whole prison, and then, with his business savvy, sell it back to the State at a profit. And now he wants to bring Lewis under his wing and be a card dealer for him.

This he does by sending his head underling as an emissary to invite Lewis into the fold. Now, when he isn’t cooling his heels in prison, Vince Greeson (Dell) serves as an enforcer / torpedo for the mob, making him very persuasive when he needs to be.

Thus, Lewis accepts the proposition, knowing this will help keep the guards off his back. Time passes, and Lewis soon works his way up the ranks in Sal’s penal organization. And then, on one particularly fateful day, Lewis sniffs out an assassination attempt on Sal and takes a shiv in the back meant for the mobster. This is a debt that Sal won’t soon forget.

More time passes, and after Vince finishes his sentence and is released, Lewis gets into it with the guards again and is put in solitary confinement, where he meets a new best friend -- a cockroach, that he feeds and asks for advice. (And the scary thing is: he listens to it!)

Eventually, Lewis is released back into the general population not long before Sal’s sentence is finally up, too. But before he goes, the old gangster tells Lewis that he’s fixed his next parole hearing, meaning Lewis will be out of jail in four months. The old man also gives Lewis his phone number and a promise that if he ever needs any help, all he has to do is call. Lewis is grateful, but warns that with the game he’s about to play, Sal won't want any part of it.

Thus, with the help of Sal's greased wheels, Lewis is soon processed out as an early parolee. Taking the bus back home, he finds Susan at the terminal waiting for him. Still bitter over her perceived betrayal, the man ignores her but can't do the same for Deputy Sam Perry (Peters), who is there to remind Lewis that as a parolee, he must register with the local authorities within 24-hours.

Promising that he'll do just that, Lewis also has a change of heart and reconciles with Susan. When asked why she abandoned him, Susan breaks down and finally tells him about Morello's goons -- and what they did to her, which only fuels the wronged man’s fire for some Old Testament-style vengeance. His girl also reveals that a lot has changed during his four years in prison:

Using Lewis’ stolen money as a bankroll, Morello is now the Mayor; Bundy has been promoted to Sheriff; and Ney is the District Attorney. This seismic shift in power is too big of a coincidence for Lewis. Swearing that he’ll punish the whole bunch for what they did, to both of them -- though Susan just wants him to let it all go -- Lewis is now locked-in on who screwed him over; but first, he wants to find out why to make sure he nails everybody.

Later, Perry tracks Lewis down at the Starlite. Apparently, Perry is one of the good guys who doesn’t like what Morello and his cronies have done to their town. Thinking that perhaps they can do each other some good, Perry tells Lewis that on the night of the incident on Talbot Road, there was no record of a reckless driver in the dispatch log. But two days later, however, one mysteriously appeared.

And it gets better: one of the cars he described belonged to the son of a Senator Tatum, a known drug addict, who apparently fell off the face of the Earth not long after.

Intrigued, Lewis asks Perry to check on the other car he saw that night. After they split up, Lewis returns home, where a shadowy figure points a gun at him! But it’s just Vince. However! Turns out Vince is here on business -- that business being Lewis, who someone put a contract out on that was assigned to his old prison buddy.

But Vince has no intention of killing him -- at least not yet, and decides to warn his friend first. Here, Lewis calls Sal Vicarronne to cash in on that favor. Thus, Vince no longer has to kill Lewis; but Sal warns that several other hitmen are converging on him.

Lewis says no worries, he can handle that; but he does ask if Sal has any dirt on Senator Tatum -- or where to find any. Feeling all politicians are shit-birds that should be avoided, Sal still promises to look into it. He also lets Vince stick around to help out all he can. The men then head out to a bar and have a drink, where they hatch a plan and then split-up to implement it, including taking out one of Larch's detectives rather cleverly, who intended to beat Lewis to a pulp, making it look like an accident.

Later, when Lewis returns home, he finds Perry lurking in his garage. But the deputy shouts a warning, saying he spotted two shady-looking men enter the house. Apparently, those hitmen Sal warned him about were already there. But with Perry’s help, they manage to take out the killers and find Susan tied up inside, shaken but relatively unharmed.

As they untie her, Perry decides they'd better treat this as a burglary gone bad. It's obvious who hired the hitmen, but they don't want to tip their hand to Morello just yet.

Then things really start to fall into place when Perry tells Lewis that a well known drug dealer used to drive a Plymouth, and both the dealer and the car disappeared about the same time Lewis killed the rogue cop. And later, Sal calls back and says the reason no one’s heard from Tatum’s son was because he apparently died of a drug overdose just two days before the same incident and the Senator covered it all up.

With that final piece of the puzzle, when the resulting picture it finishes finally comes into a sharp focus, at last, it's time for some payback.

To start, while Vince checks out the security on Morello’s fortress home, Lewis heads to the State Capitol to shakedown Tatum. But he’s hijacked along the way by the same men who raped Susan way back at the beginning of the film.

But using a moving train as a speed bump, Lewis manages to escape while leaving the bad guys to be smeared all over the tracks. (More on this incredible set-piece and insane stunt in a minute.) Save for one (Mantee), whom Lewis brutally interrogated by first blowing off one ear with a pistol before burning the other with a contact breaker off his car’s engine. And after the man spills his guts, Lewis shoots him dead.

With things rapidly falling apart on him, Morello puts out the order to shoot Lewis on sight. Meanwhile, outside his perimeter fence, Vince carefully cases the joint, taking special notice of the patrolling Doberman Pinschers.

After wrapping up his impromptu detour, Lewis abducts Senator Tatum right off the state capitol building steps, takes him to a secluded spot, and beats out a confession. Turns out it was Tatum (Brooke) who had shot at him that night on Talbot Road. Seems the Senator drove his son’s car to meet that drug dealer, whom Tatum felt was responsible for his son’s death, and killed him -- and then Lewis just happened upon the wrong place at the wrong time.

In a panic, Tatum called Morello and gave him Lewis’s description. The shady Morello then promised to take care of everything, with some special favors from the senator as payment for his continued silence.

Here, the man claims he’s been just as much a victim as Lewis thanks to Morello. This persuades Lewis not to kill him.

Still needing corroborating proof of all that corruption and graft, as Lewis and Vince prepare to assault Morello’s mansion to get it, Susan once more pleads with her man to just call the whole thing off. But even she knows this is a futile gesture.

Lewis, you see, says he has to finish it. He had everything he ever wanted, and then Morello took it all away. Then, as the men leave, a distraught Susan warns that she might not be around when they get back -- if they get back at all.

But the chips are on the table. And after sneaking onto the estate grounds, killing one of the guard dogs in the process, Vince and Lewis find Ney and Morello inside, where they convince Morello, at gunpoint, to open his safe.

Inside the strongbox, Lewis finds all of the records of bribes and payoffs, and a large sum of cash.

Alas, with victory in hand, one of Morello’s guards stumbles upon them. And as mayhem ensues, Vince and the guard manage to shoot each other dead. Lewis then punches Morello through a big picture window; and when the villain lands outside, the other guard dog attacks and kills him.

Back inside, as Ney tries to strike another deal, claiming he was another strong-armed victim of Morello, Lewis pistol-whips his former lawyer. He then gathers up all the documents, the money, and splits, with the sounds of Morello being fatally mauled playing us out of the scene.

Returning to the Starlite, a relieved Lewis finds Susan still waiting for him. Told to pack up, because they both need to get out of town real quick-like, Susan refuses to run away and begs Lewis to stay, too. But the gambler in him says the odds are better to fold and walk away -- and walk away he does, leaving the heart-broken Susan behind.

But once out in the parking lot, Lewis has another change of heart and heads back inside, where he tells Susan to call Perry, whom they will turn all the incriminating evidence over to -- but not until after they hide that money first.

There was a persistent rumor that the real reason Joe Don Baker abandoned the role of Buford Pusser in the Walking Tall sequels was because he and Pusser did not get along, with one report claiming he had referred to Pusser as a “fascist pig.” A report Baker would vehemently deny, claiming, “It’s a lie, plain and simple.” (The Macon News, August 26, 1974). He would also clarify that he refused to star in the sequel because he felt Pratt and Bing Crosby Productions were treating Pusser unfairly and had tried to rip him off.

Said Baker, “The script for the sequel is lousy. It’s all fiction.” (The Tennessean, August 24, 1974). In the same article, Baker would claim Pratt and BCP tried to kill Walking Tall on its release and used the initial bad reviews and poor box-office in an effort to sabotage bookings, “until it made about $35 million, and all of sudden they jumped on it with both feet.”

Buford Pusser (left), Joe Don Baker (right).

This, of course, contradicts Pratts’ proclaimed efforts to salvage the film. Baker would also claim that Pratt kept after him for over a year and a half to reprise the role but he refused, telling his friend Pusser he would not do it.

After some digging, I think the ‘fascist pig’ comments can be traced back to an interview Baker did with Dees Siegelbaum for The Macon News (June 20, 1974) while shooting Framed, but I think Baker’s biggest concern was a fear of typecasting mixed in with a rant on disgraced President Richard Nixon and his “get tough” on crime policies as it all went down in flames after the Watergate Scandal broke.

“I’m not Buford, though the name they remember is Buford,” said Baker. “I don’t know what side Buford’s on right now. A couple of years ago he was for the establishment. I have no respect for law and order but I’ve got a lot of respect for justice. But I’ve always been against Nixon, forever. Nixon -- those people’s concept of law and order, I spit on it. If Nixon and his bunch are law and order then I prefer a revolution.”

Before signing off on Walking Tall, Pusser had negotiated a deal that would give him seven-percent of the box-office take. And by my math, seven percent of $35 million is around $2.5 million -- though I have no idea if BCP was cooking the books and screwing Pusser out of his share, as Baker never really expanded any further on how he felt they were ripping him off. Both the windfall and the film would cause a lot of hard feelings locally, and Pusser would lose his reelection bid.

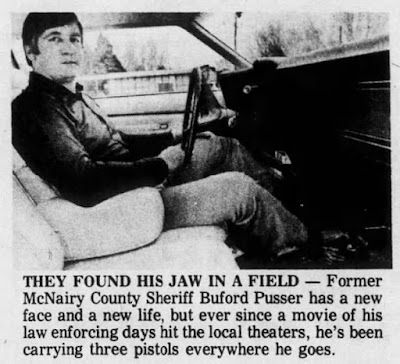

Kingsport Times-News (April 15, 1973).

Meanwhile, Pusser would also tamp down the alleged feud with Baker, saying, “As far as I know, we are friends.” In fact, Pusser would have a huge impact on Baker’s next picture, too, when it came to relocating the action from Ohio (novel) to Tennessee (film).

“We came down in March to look Nashville over [for Framed], and quite frankly we were about ready to leave,” said Joel Briskin (The Tennessean, June 23, 1974), who was Mort Briskin’s son, and who would serve as a co-producer and location scout for the film. “Coming to a strange town is almost like going to a foreign country. We didn’t know where to go, where to find good locations, or even where to get a doctor if we needed one.”

But then Pusser reached out to Glenn Ferguson, a Nashville Metro Trustee, and pointed him toward the younger Briskin. “Ferguson literally took us in hand,” said Briskin. “The first day he drove me around and showed me location possibilities. It was one of the most successful location days I’ve ever had. The cooperation was just fantastic. We met cooperation on every level of government and the nightclubs on Printer’s Alley really opened up to us. People let us film in their homes.”

And to quash the feud rumors for good, Baker would state he and Pusser stayed at each other's homes and constantly “honky-tonked” together while filming Framed in Nashville. (For those unfamiliar with the vernacular, it means they went out and drank together at dive bars and juke joints.) Meanwhile, Pratt would push on with his sequel for Walking Tall, and had apparently found his new leading man.

The Jackson Sun (August 21, 1974).

On Tuesday, August 20th, 1974, the UPI reported Buford Pusser had held a press conference in Memphis, announcing he would personally star in the sequel to Walking Tall (The Tyler Morning Telegraph, August 22, 1974). “I’ll be frank,” said Pusser. “This whole thing frightens me. But I went to Hollywood for a screen test and it worked out.” The new film to be was tentatively titled Buford.

Two days later, Pusser was dead, a victim of a car wreck, when he apparently lost control of his new Corvette on a curve just hours after he’d signed a contract to star in Buford. The victim was alone in the vehicle, and while investigators found nothing suspicious in the burnt-out wreckage, others would persist for years that this wasn’t an accident but retaliation.

The Tennessean (August 24, 1974).

Regardless, Baker would serve as a pallbearer at Pusser’s funeral. Said Baker, “I guess some people could say I’m here to make myself look good. [But] I’m here because I loved him. He was a hero to me.” (The Tennessean, August 24, 1974).

Pratt would go on to produce the oddly titled Part 2: Walking Tall (1975) and Final Chapter: Walking Tall (1977), starring Bo Svenson, who was Pusser’s original choice to portray him but settled for Baker. And Mort Briskin would write the screenplay for the telefilm A Real American Hero (1978), a less fictionalized and more definitive account of Pusser’s legacy, with Brian Dennehy taking over the role of Pusser.

The Atlanta Journal (January 31, 1975).

1973 would be a huge year for Joe Don Baker. The tall and burly Texan, with the beady eyes and perpetual squint offset by a charming smile and friendly drawl, had spent two years in New York City after a brief stint in the Army, working as a hotel clerk, a waiter and salesmen while attending the Actor’s Studio.

Said Baker (The Knoxville News-Sentinel, January 13, 1974), “I did a lot of college drama [at North Texas State], but actually I had started thinking about becoming an actor long before that. No big bolt of lightning struck me. I used to go to the movies and see those guys making love to beautiful women. I figured it would beat pumping gas.”

The Los Angeles Times (September 3, 1975).

After appearing in a couple of shows on Broadway, Baker had been kicking around episodic television since he first appeared in an episode of Honey West (S1.E15, 1965) as a truck driver fired for allegedly drinking on the job, who hires West (Anne Francis) to clear his name.

There would be a few film roles in between all those TV guest spots. Baker would be uncredited for a bit part in Cool Hand Luke (1967), and he would play Slater, the bitter, ex-confederate amputee with a death wish in Guns of the Magnificent Seven (1969); but it was mostly TV work on shows like The Big Valley (S4.E17, 1969), Bracken’s World (S1.E15, 1970) and The High Chaparral (S4.E16, 1971).

Fun Fact: in the alt-history of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… In Hollywood (2019), the character of Rick Dalton kinda-sorta beats out Baker in the director’s fictionalized universe for a guest shot on Lancer (1968-1970). In our timeline, Baker starred as the villainous Day Pardee in the series’ pilot episode, The High Riders. In the Dalton timeline, he played a character called Decoteau.

Baker also starred in an excellent Made for TV-Movie called Mongo’s Back in Town (1971), another tale based on a book penned by a convicted killer, Emil R. Johnson. Baker played the title character, a contract killer, who is opposed by a cop played by Telly Savalas. The whole thing felt like a bit of a dry run for The Marcus-Nelson Murders (1973), another telefilm, from which the series Kojak (1973-1978) sprung.

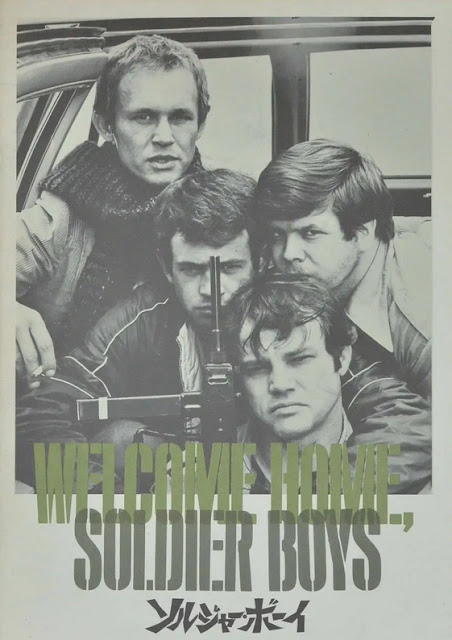

Meanwhile, Baker started accruing a few more big screen credits, too, appearing in the western Wild Rovers (1971) and would receive top-billing in the offbeat Welcome Home, Soldier Boys (1971), Richard Compton’s early and eerie take on returning Vietnam veterans (Baker, Paul Koslo, Alan Vint and Elliot Street), who are disgruntled and not adjusting very well as they try to re-enter a society that has either passed them by or holds them in contempt. The film is a slow burn, but the payoff is a rocket-punch to the gut when these ex-soldiers decide to bring the war home with them.

But Baker’s big breakthrough came the next year when he co-starred in Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner (1972), playing Steve McQueen’s slimy brother, Curly Bonner, who sold out the old family homestead to make way for a trailer park. A lyrical ode to dying breeds and for a time long past its expiration date, the film would fizzle at the box-office.

This setback didn’t set back Baker much, though, as he officially broke out in ‘73, starring or co-starring in Don Siegel’s Charley Varrick (1973), John Flynn’s The Outfit (alias The Good Guys Always Win, 1973), and Walking Tall (1973). In that first film, Varrick (Walter Matthau) robs the wrong bank that was laundering money for the mob, who sends a brutish and sadistic enforcer named Molly (Baker) to retrieve the cash.

“In this amoral, extra-legal, unethical framework of Charley Varrick, the winner is the one who murders everyone else before they murder him,” said Sidney Graham (Contra Costa Times, December 5, 1973). “The machinations of Matthau are interesting, but his shambling coziness may deceive us into the belief that he is less sadistic than the other characters. Baker plays a sadist programmed to track and murder and to beat up anyone who deters him in the slightest.”

And George Anderson called Baker’s performance “a menace worthy of the homicidal automaton portrayed by Lee Marvin in Siegel’s The Killers (1964).” (Pittsburgh Post Gazette, October 26, 1973).

In the second film, a loose adaptation of one of Donald Westlake’s Parker novels, professional bank robber Earl Macklin (Robert Duvall) is released from prison, only to find out the last bank he robbed was another mob front and is now being targeted for assassination. Macklin contacts his old friend, Cody (Baker), and they set out to do unto the mob before they can do it unto them with a lethal prejudice.

“There is a roundness of characterization, a brush of reality and a kind of continuous surprise in The Outfit,” noted Charles Champlin (The Los Angeles Times, October 2, 1974). “Duvall is good, as always. [And] Baker was one of the very best actors around long before Walking Tall made him a folk hero, and he demonstrates it again here.”

And the topper for that year was, of course, Walking Tall, which we’ve already covered. Thus, Baker was red hot and a bona fide box office draw when Paramount signed him to star in Framed, and other studios would soon be knocking on his door to hopefully catch some of that magic, too.

As for his co-stars, born in Virginia but raised in Detroit, Michigan, at the age of 14, Conny Van Dyke was elected Miss Teen USA by Teen Magazine in 1959. And by the time she was 15, Van Dyke had signed on as a singer and songwriter for Wheelsville Records, hosted her own local TV-show, worked as a fashion model, and starred in her very first film; a bit part in an early vanity project of Tom Laughlin’s called The Young Sinner (alias Like Father, Like Son, alias Among the Thorns, 1965), which was also his directorial debut. And for those of you out there who found Laughlin’s Billy Jack (1971) films insufferable, this one will melt your faces right off.

Then, when she was 16, as the legend goes, Van Dyke was performing at a drive-in theater concession stand when she was discovered by a representative of Motown Records, who introduced her to Smokey Robinson, who then introduced her to Berry Gordon and helped to get her signed onto the label in 1961, making her one of the first white recording artists for Motown.

But aside from touring with the likes of Stevie Wonder and Martha and the Vandellas, with several harrowing tales of prejudice picked up along the way, this only mustered one single release, “Oh Freddy,” which was written by Robinson with back-up vocals provided by the Supremes. On the B-side was an old Marvin Gaye song, “It Hurt Me, Too.”

But as that contract fizzled and the 1960s progressed, Van Dyke kept singing and modeling, and even served a stint as a Rockette at Radio City Music Hall for a spell. She would also appear in local radio and TV commercials in Detroit, where she would serve as the original Dodge Rebellion Girl before giving way to Pamela Austin and Joan Parker on the famous campaign.

Van Dyke also found a niche by appearing at auto shows as a spokesmodel, where she was spotted by Tom Stern and eventually cast into Lee Madden’s Hell’s Angels ‘69 (1969), an outlaw biker / casino heist flick (-- and nowhere near as exciting as all that sounds), which co-starred Stern, Jeremy Slate, and the original Oakland chapter of the Hell's Angels, led by Sonny Barger -- the same group that had curb-stomped author Hunter S. Thompson. Van Dyke would later describe filming the movie as “a terrifying, and yet, exhilarating experience.”

Having survived that harrowing shoot, Van Dyke then packed her bags and moved to Los Angeles, where she caught on at Universal, appearing in episodes of Ironside (S2.E1, 1969) and Adam-12 (S1.E23, 1969). But not long after, Van Dyke decided to shift gears again, moved to Nashville, and produced and released two country albums, the self-titled Conny Van Dyke and Conny Van Dyke Sings for You for Dot Records.

And she was still in Nashville when it was announced that producer Stanley Canter was going to be shooting a new movie there. It was set to be directed by John Avildsen, and would star Burt Reynolds and Art Carney, but Canter couldn’t seem to find his leading lady. He needed an actress who could handle a southern accent and sing country music.

Both Dolly Parton and Lynn Anderson had already turned him down, and “I’d seen it in the paper, they were casting this girl opposite Burt Reynolds,” Van Dyke said in an interview with Skip Lowe (2000). “And I thought, gee-whiz, why isn’t my agent calling me for this? I called them and they said, ‘Connie, you’re too old.” (She was 28 at the time.) Undeterred, Van Dyke and her manager / husband went to the Vanderbilt Hotel, where Canter was staying during his Nashville recruitment drive, and bluffed her way past the clerk.

“I told them I had an appointment, [which] I did not.” She then bullied her way into the producer’s room, literally sticking her foot in the door, and blustered inside. The only problem was, Canter wasn’t there.

Luckily, he was just a few stories below in the hotel restaurant, and was called back to his room to deal with this unruly intruder. But Canter was impressed with this woman’s chutzpah, and watched while Van Dyke did an impromptu audition on the spot. “And that’s how I got the part.”

The film was W.W. and the Dixie Dance Kings (1975), a comedy crime caper film, where Reynolds played a bandit with a heart of gold, who hijacks Van Dyke’s tour bus and coerces her and her band into helping him rob a bank. But once they see how much money he’s absconded with, they officially become a gang to help finance their big breakthrough. More robberies follow, and all the while they are pursued by a kooky lawman played by Carney while Reynolds tries to get into Van Dyke's pants.

It was only her second featured film, and to her credit, Van Dyke steals the majority of her scenes from Reynolds -- no small task, which impressed the actor greatly. Meanwhile, as filming wrapped up on W.W. and the Dixie Dance Kings, Briskin and Karlson were also back in Nashville, setting up to shoot Framed in nearby Smyrna. And as it just so happens, they were also looking for an actress to play Joe Don Baker’s love interest.

“If it wasn't for Burt Reynolds, I wouldn’t have gotten my next film [Framed], which I shot ten days after W.W. wrapped,” Van Dyke told Lowe. “[Burt] made a phone call to Mort Briskin, Phil Karlson, and that got me that opportunity and I’m proud to say I didn’t let him down. He had a lot of faith in me.”

As written, Susan Barrett is a pretty thankless role. She’s essentially there to be used by her boyfriend and abused as a manipulated pawn by those conspiring against them. If its any consolation, the character was treated way worse in the source novel.

But! It should be noted that in the film’s excellent commentary track, available on the Kino Lorber release of Framed, Howard Berger and Nathaniel Thompson reported Van Dyke later revealed there was a scene that got cut, where Lewis rapes and sodomizes Susan after he’s released from prison as a form of punishment for betraying him. A cut Van Dyke regretted because she felt it was some of her best work in the film.

But this was a step too far for Briskin and Karlson as they felt it would villainize their main character too much. But there is evidence of its aftermath still in the film, which recontextualizes the whole scene, as one can easily read the ‘come the dawn’ moment where Lewis and Susan reconcile in bed after having sex off-screen that it might not have been as consensual as we thought given her shamed and cowering posture, hiding under the covers.

And that was one line Van Dyke would not cross for them: she refused to do any nudity. “If I can’t show it through my face and through my eyes, I better go back to baking pies,” she said (The Macon News, June 20, 1974).

Briskin and Karlson would also change the book’s ending, which ends on kind of a bummer, where Lewis does leave Susan behind and becomes a hitman for Sal’s organization. Instead, they chose to have Lewis turn all the evidence over to Perry while Susan clumsily hides the satchel of Morello’s cash in the cooler, which we presume they will use to live happily ever after.

Now, admittedly, those plot-specific torch songs she sings about her lover throughout the movie are rather insipid, penned by Arthur Kent and Frank Stanton; but the singer does her best to sell the hell out of them anyway. The one musical exception was the title song, “I’ll Never Make it Easy,” which is easy on the ears and would be released as a single by ABC-Dot.

Thus, Van Dyke’s biggest regret about the film was how she wasn’t allowed to write her own material, telling Christopher Wright (The Tampa Tribune, July 25, 1975), “I wanted to do my own stuff in the film, but they (the men who make decisions in the movie business) think people can do only one thing at a time. They thought I couldn’t write music for the movie without detracting from my acting. But being of reasonable intelligence, I can walk and chew gum at the same time.”

At the time of the film’s release, Karlson felt Framed was going to make Van Dyke a major movie star, telling The Times-Tribune (September 19, 1974), “Burt Reynolds recommended her to us. I was a little leery to cast her as Joe Don’s leading lady but she handles the heavy drama like a young Bette Davis.”

But unlike Monroe, Framed would be Van Dyke’s last feature film despite signing a contract with Paramount for two more features, which was too bad. She was a bit raw, but there was something there that a little more cultivating in the right hands could’ve really led to something.

After, she appeared in a couple episodes of Police Woman (S1.E7, S2.E13, 1974-1975) and Barbary Coast (S1.E6, 1975) before finishing out the decade by being a regular on several daytime game shows, ranging from Tattletales to Cross-Wits to filling in the blanks on Match Game. Van Dyke would then move to Florida to raise her son, where she would serve as a law enforcement officer, before staging a brief comeback in the aughts until a debilitating stroke in 2009 saw her retiring for good. She would pass away in November, 2023.

Gabriel "Gabe" Dell, meanwhile, was one of the original Dead End Kids, who made the jump from the stage version to the filmed version of Dead End (1937). And he would stick with them, off and on, over the next three decades through their many permutations as a kind of floater, meaning he wasn’t always a member of the gang but played a former member in trouble or an outside character on which most of the plots revolved around.

(That's Dell in the back, partially obscured by Humphrey Bogart.)

Aside from his work as a Dead End / East Side / Little Tough Guy / Bowery Boy, Dell is probably best remembered for his work on The Steve Allen Show (1956-1960), and most notably there for his role as Boris Nadal, a vampire spoofing Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula. “The Vampire Umpire” skit is pretty funny, and at last check it was available on YouTube. But there’s another skit with Don Knotts, another Allen regular, as Renfield, which was even better -- but do you think I can find a copy of it now?! Hell no! Of course not.

Dell would also provide the voices of both Dracula and Frankenstein’s Monster for the novelty album Famous Monsters Speak (1963), a spin-off of Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine. (And on second check, it appears Dell provided all the voices on that record.) Allen would later quip when people did an impression of Lugosi’s Dracula, they were really doing Dell doing Lugosi doing Dracula.

The actor would spend most of the 1960s splitting time between the stage and episodic television before returning to features with Who Is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me? (1970) and Earthquake (1974) before signing on to play Vince Greeson in Framed. Briskin described Dell’s character as a “Dead End Adult.” (Atlanta Constitution, August 10,1974).

“I play a hired assassin,” Dell told Bailey (The Tennessean, May 26, 1974). “Known in the trade as a button man. It’s a big challenge because I never played a part like that. I meet Joe Don and John Marley in prison -- which we filmed out here at your state prison.”

The Tennessean (May 21, 1974).

Bailey described Dell’s voice as soft but tough, emitting a feeling of both kindness and danger, saying it wouldn’t be difficult to imagine him as a killer at first, until he revealed a strange gentle side. Said Dell, “The prisoners out there were really cooperative. It was thrilling to work with those boys in there -- insofar as they had a week of something different in their lives. We all felt very deeply about the situation. In fact we were depressed for about three days.”

In the same interview with Bailey, John Marley called Dell, despite his hard demeanor, a big softie. Marley, of course, despite being an actor since bit parts in Native Land (1942) and Kiss of Death (1947), will always and forever be remembered as Jack Woltz, the film producer who wakes up next to a decapitated horse head after he refused an offer from The Godfather (1972).

And it wasn’t just Dell and Marley. Everyone involved with filming at the prison came away with some emotional baggage over what they had seen and experienced. “I felt like I’ve done time,” Baker said mournfully (The Macon News, June 20, 1974). That’s correct. Not only was the film shot at the Tennessee State pen, but the actual convicts were used as extras -- and not just a few of them. But the entire week of filming at the prison was completed without any incidents.

Some of this could be chalked up to good timing, as about a year later, right about the time Framed hit theaters, the infamous Bologna Riot took place at the prison. Apparently, the inmates were upset about a snafu that saw bologna on the menu instead of the promised pork chops. (A later report said they didn’t have enough chops for everyone, and those at the end of the line who got stuck with bologna weren’t happy.) When the dust settled after the National Guard was called in, one inmate was dead and another 39 were wounded, including two guards, with ten being shot. But don’t kid yourselves, the grievances went well beyond any lunchmeat disputes.

Other celebrities had appeared there. Johnny Cash performed there several times and even recorded a live concert album, Behind Prison Walls, with Linda Ronstadt, Richard Pryor, Carl Perkins, Foster Brooks and Roy Clark. After the prison closed in 1992, they filmed the Cash biopic, Walk the Line (2005) there. And Frank Darabont would use the prison’s interiors for The Green Mile (1999). But none of them filmed while it was occupied, and they didn’t see the whole picture.

“We have something to say in the picture, I think, about the system,” said Briskin. “You have a situation where people can relate as human beings, it affects their lives, they see something of where they’re at. I sure heard some stories. I’m going to get involved. We’re all sitting back. People from the outside world should take a look.”

Both Dell and Marley add a lot of gravitas to the film, as do fellow character actors like Brock Peters, Warren Kemmerling, Paul Mantee and John Larch.

Peters is probably best known for playing Tom Robinson, whom Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch defends in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) or as Charlton Heston’s boss in Soylent Green (1973) -- a film whose final punchline gets less and less funny each year as things continue to collapse around us. Peters also produced the satire Gone Are the Days (1963) and Five on the Black Hand Side, who’s Blaxploitation title is a tad misleading and sells the film way short.

Kemmerling is one of those guys who you always recognize but can never quite remember his name. Most will recognize “that guy” for his role as the military commander in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), who makes the decision to use nerve gas to clear the area around Devil’s Tower. Or as the General who rounds up Raymond Burr in the American inserts for Godzilla 1985 (1985). And sharp-eyed weirdos like me will also spot him as the captain of the Ellen Austin in the faux doc, The Bermuda Triangle (1979). Also, the delivery of his line during Framed’s climax, “You rat-fink bastard,” is just [chef’s kiss].

Mantee sort of made a career out of being a second banana or third thug on the left, but there were a few starring roles, most notably as the marooned astronaut in Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964) and Breakout (1975) with Charles Bronson. And judging by the way he authentically sells being tortured by Baker with a spark plug wire stuck in his ear, his career probably deserved better.

And Larch was a Karlson regular since The Phenix City Story, where he played the despicable Clem Wilson. He was also a favorite of Clint Eastwood, having appeared in Play Misty for Me (1971) and Dirty Harry (1971). Others will remember him as one of the family members tortured by Bill Mumy in the classic Twilight Zone episode “It’s a Good Life” (S03.E8, 1961).

I liked how he played Bundy as someone in over his head, caught up in the wake of Morello’s lust for control. The plot they’re all trying to make work is pretty threadbare, strung together by several action set-pieces as they keep plugging up all the leakage to keep things afloat. And the film just improves all around, exponentially, whenever Sal or (especially) Vince are on screen.

All told, Framed was a five week shoot and was filmed strictly in Tennessee. Aside from the prison scenes, the rest was shot in and around Smyrna, Tennessee, which is just a little southeast of Nashville, using actual locations like the Starlite Lounge. The Starlite would actually remain open until 2014 and, get this: apparently, it was built from the remnants of a mansion that was burned down in 1899, set on fire by its owner after he murdered his entire family before hanging himself in a nearby barn. His total body count before that depends on who is telling the tale.

And as a surprise to no one, the property was allegedly haunted, with people spotting ghosts in Victorian attire pacing the hallways, the sounds of children crying, and other assorted poltergeist activity since it opened back in 1952. And as of 2017, tours were available if you’d like a chance to see an authentic ghost. Just Google “Beast House” and “Nashville.” Get those tickets now!

Other filming locations included the aforementioned bars along Printer’s Alley, including The Embers Lounge, Jefferson Square, and the city’s industrial district, where they shot the infamous train collision.

Now, at the time of this writing, a clip of this incredible, nearly gone awry stunt has been making the rounds online ever since comedian Patton Oswalt talked about it on Conan O’Brien’s podcast, Conan Needs a Friend (Episode No. 242, July 17, 2023). The stunt coordinator on Framed was the legendary Carey Loftin, and odds are good that was him pulling that gag off and barely escaping the tremendous fireball. (Sharp eyes will also spot Loftin playing one of the assassins trying to take Susan as a hostage, who is gunned down by Perry while trying to escape in a car.)

Loftin had cut his teeth as a stuntman working in the rough ‘n’ tumble, ‘no piece of furniture escapes unscathed’ world of the matinee serials -- Perils of Nyoka (1942), Secret Service in Darkest Africa (1943), and The Purple Monster Strikes (1945) to scratch the surface.

In the 1950s he served as a stunt coordinator on 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), would be Spencer Tracy’s double in Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), and staged another spectacular car chase and crash for Thunder Road (1958), where Robert Mitchum plows his ‘57 Ford Fairlane, filled to the brim with moonshine, into a power transformer where it promptly explodes.

In the 1960s he was probably most famous for doing stunts on The Great Escape (1963) and Hatari! (1962), and orchestrating a lot of the chaos on land, sea and air for It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963), The Great Race (1965) and Munster, Go Home! (1966).

Then, as we moved into 1970s, Loftin would serve as a stunt driver, delivering the goods on Bullitt (1968), The French Connection (1971), Vanishing Point (1971) and Duel (1971) -- that’s him, well, his arm and feet, playing the phantom trucker out to kill Dennis Weaver.

Carey Loftin (left) on the set of Bullitt.

Loftin had worked with Karlson on the Matt Helm pictures and would do so again on Walking Tall before tackling Framed. Again, the all-out slobberknocker between Lewis and Haskins is one for the ages, but that train stunt belongs in the Hall of Fame of such things.

If you look real close, there’s a quick slip of the frame that shows the cast and crew gathered on the road to watch the filming of the stunt. It feels like a one-off, meaning if they didn’t get it on the first try they weren’t going to get it at all. There’s a little more control since they were only dealing with the train engine with no rail cars but, still, it’s not like that thing would’ve been able to stop if Loftin failed to bail out in time.

Tim Smyth was in charge of the film’s special effects, making him responsible for the enormous fireball on impact, which appears to be a lot bigger than expected as you watch (a presumed) Loftin scramble, and then scramble some more, to get out of the way. A happy accident or a lucky accident, the end result is nothing short of spectacular. (If you look close at the last frame of the sequence below, on the bottom right, you can see the stuntman survived.)

This sequence would be a rare flash of brilliance for Framed’s director of photography, Jack Marta, who, unlike Karlson’s other collaborators behind the camera, kinda failed to hold up his end of the stick.

Marta’s career can be traced back to the Silents -- What Price Glory (1926), The Red Dance (1928). He bounced around a lot but spent most of his time at Republic, where he shot things like David Miller’s Flying Tigers (1942); one of Roy Roger’s better efforts in The Golden Stallion (1949); and my favorite take on the Alamo with Frank Lloyd’s The Last Command (1955).

Also, before I forget to write it down, Marta also lensed one of the strangest murder mysteries I’ve ever come across with Howard Bretherton’s Whispering Footsteps (1943), where a man sort of frames himself to teach his snooping boarding house neighbors a lesson. Sorry, the jury is still out on whether that’s a 'bad' strange or a 'good' kind of strange. Thus, the internal debate continues.

In the 1950s, like a lot of his brethren, Marta would find a second life shooting films for the independents. He helped Bert I. Gordon bring about the Beginning of the End (1957), and a nice little juvenile delinquent / noir film with William Witney called Juvenile Jungle (1958), where we’re not sure if we’re dealing with a femme fatale or a homme fatale as both lead each other down the inevitable road to ruin. And he would team up with Witney again, another unheralded director, on the similarly themed Young and Wild (1958).

Marta would then follow Gordon to American International Pictures, where they would collaborate on War of the Colossal Beast (1958) and The Spider (alias Earth vs. the Spider, 1958). And as the 1960s expired, he would move back up the studio chain a bit, shooting Cat Ballou (1965) for Columbia, The Perils of Pauline (1967) for Universal, and Plaza Suite (1971) for Arthur Hiller, Neil Simon and Paramount.

But after that, Marta would be relegated mostly to television. He would shoot seven episodes of Batman (1966-1968), tilting the camera to William Dozier’s specifications -- those villains were crooked, after all; five episodes of The Green Hornet (1966-1967); and about a half dozen telefilms, including running the camera for the aforementioned Duel, Steven Spielberg’s ode to Road Rage, where he first had the opportunity to work with Loftin.

And to tangle up those threads even more, Marta would also shoot The Trial of Billy Jack (1974), The Master Gunfighter (1975) and the nigh insufferable Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977) for Laughlin.

Like Briskin, Karlson and Baker, Marta would also be a holdover from Walking Tall, and his efforts on Framed would be fairly lackluster. Everything looks flat, the colors are dull, and the camera appears to be on constant lockdown, making things seem inert as scenes drag on interminably in the unwavering master-shot. Sadly, a lot of films of this era were shot that way, to make them ready-made for television. (Pan and scan really wasn’t a thing yet.)

And it's hard to believe that the same guy who edited together masterpieces like Robert Siodmak’s The Spiral Staircase (1946), Mark Robson’s Champion (1948), and Joseph Lewis’s Gun Crazy (1950), and who had managed to keep the insanity in frame for Batman: The Movie (1966), provided the same listless efforts on Ben, Walking Tall and Framed.

But there he is in the credits, editor Harry Gerstad. May Frank Miller shoot me dad (-- no, not that one, the other one), but the man assisted Elmo Williams on High Noon (1952) fer heaven’s sake, one of the most tight and taut and tension filled movies ever made. *sigh*

Once filming wrapped and Gerstad started stitching the film together, it was announced Framed would hold two world premieres in October of 1974 -- one in Nashville proper and a special screening at the State penitentiary. “We’re planning to do it up big,” said Joel Briskin (The Tennessean, June 23, 1974). “There will be press from Chicago and New York, we’ll be bringing the stars back for it and there will be a lot of executives from Paramount. There will probably be a formal ball.”

But this wasn’t set in stone, apparently, as all efforts to find documentation that this actually happened has been maddeningly elusive (-- several local papers covered the film during production but not a peep after), and the film wouldn’t be released proper until 1975. (Again, if anyone has actual documentation that this did happen, let me know.)

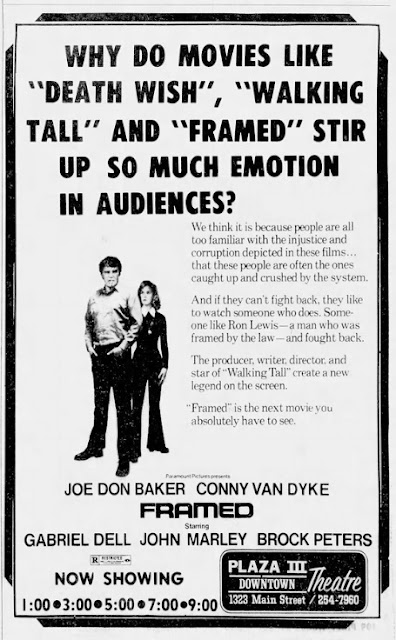

Here, having learned their lesson with Walking Tall, Briskin and Paramount rolled out Framed in the south first, with the earliest screenings appearing in South Carolina in March, 1975, where it drew some harsh critical reaction.

The State (March 7, 1975).

Pat Berman decried the film for The Columbia Record (March 15, 1975), calling it “Repulsive, tasteless, revolting, mindless -- pick an adjective and you will have an accurate description of the quality of director Phil Karlson’s new film Framed, a trashy, low-budget debauchery that is alternatively sadistic and then dull. It’s truly the audience that gets framed.” Framed for what, exactly? Still, we get the point.

From there, the studio tried to dress up Framed with the same grassroots hoodoo that sold Walking Tall to the masses as the film made its wider southern release in July through September before migrating north for the winter of ‘75. They needn’t have bothered.

The State (March 5, 1975).

“Framed is a portrait of how not to make a movie: sloppy dialogue, slap-dash acting, broad violence brush strokes -- everything done in bright red, as in the color of my true love’s blood,” noted Walter Herring (The Philadelphia Daily News, September 22, 1975), who saved most of his venom for fat-shaming Baker. “Utilizing his one acting expression to its fullest, the petulant pout, Baker continues his downward slide. His belt-line is outpacing his career growth. Walking tall and acting small, Baker is without a doubt the least-likable hero to come down the R-rated trail in a long time.”

Also unimpressed was Perry Stewart (Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 16, 1975), saying, “Framed, one of the more violent films in recent years, was highly touted as the reunion of the Walking Tall team: director Phil Karlson, star Joe Don Baker, and producer Mort Briskin. [But] Framed doesn’t walk very tall. It sort of side-winds into a story which is quite pat and predictable despite the fact that Briskin’s screenplay was taken from a novel written by a couple of Ohio convicts.”

The Austin American-Statesman (July 16, 1975).

And Brian Clark didn’t mince words when it came to the film’s violent content. “If there were such a thing as a triple-X rating for violence in the movie industry, Framed would surely earn it, and then some. Set in a nondescript town in Tennessee, this confusing film is disgustingly violent,” said Clark (The Sacramento Bee, September 22, 1975).

But not all of the reviews were negative. “Framed is one of those difficult movies to write about because it falls somewhere in that great gray area between really awful and exceptionally good,” said Christopher Wright (The Tampa Tribune, July 25, 1975). “Exactly where in there it falls will most likely be determined by individual tastes. Those who like no-holds-barred, escapist adventure fare will probably find Framed good entertainment; those who don’t will wish they’d spent their money elsewhere.”

And Tim Janes called Framed “one of those films that is hugely enjoyable in a guilty sort of way. Karlson has molded a film that extols violent personal vengeance as a praiseworthy quality and he does it very well, putting the audience in the awkward position of emotionally rooting for what they would intellectually reject,” said Janes (The Arizona Daily Star, September 6, 1975).

“The film is unabashedly a B-movie, which makes it a welcome relief from some pretentious A-movies floating around. The film has set itself modest goals, which it meets not merely competently but well. Joe Don Baker is a big, hulking menace, combining righteous menace with a winsome conviction. Framed merely takes its [revenge concept] to a logical extreme and makes a virtue out of it.”

In his review, Kevin Thomas, the patron saint of exploitation filmmakers if there ever was one, broke it down thusly. “In one aspect Framed is more intriguing than Walking Tall. As in that film law and order are so thoroughly corrupt -- everyone from the deputy sheriff killed by Baker up to a state senator is crooked -- but Framed goes one step further and presents a couple of hardened professional criminals, a wry underworld chieftain (played with wit and grit by Marley) and a hit man (Dell, ever the menschy Dead End Kid) as sympathetic characters. In short, Framed persuasively projects a world so askew that the traditional forces of good and evil are all but reversed,” said Thomas (The Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1975).

“Framed dynamically reunites the star, the writer-producer and director of Walking Tall in another bloody but galvanic exploitation picture that plays powerfully upon the widespread disaffection with corruption on all levels of society and government and creates a mythically strong hero to combat it single-handedly. On display in full force is director Karlson’s formidable gifts as a rabble-rouser: so harsh is Baker’s unjust fate that nothing he does in revenge seems unduly outrageous. Currently the most flourishing of the stylish B-picture veterans, Karlson, a Monogram alumnus, knows how to play a film fast and simple -- yet his expressiveness with the camera is breathtakingly bravura. Only a virtuoso like Karlson could make so much violence acceptable.”

Almost every review I unearthed, positive or negative, discussed the violence quotient in Framed. Most condemned it while a scant few found it cathartic. To me, with this type of unapologetic, southern-fried exploitation piece, that kind of violence was inevitable -- and expected. As Briskin rightfully pointed out, “Violence is a salable factor. People seem to be turned on by it. Maybe it’s better they get their frustrations out this way.” (The Macon News, June 20, 1974).

All told, Framed would not find a second wind like its predecessor and would be a box-office disappointment. The film would also mark the beginning of the end of Baker’s career as a leading man. His follow up feature, the much maligned Mitchell (1975), was razed critically, was a no-show at the box-office, and put the final nail in Baker's box office potential’s coffin, while Speedtrap (1977) salted the ashes.

The Macon News (September 11, 1975).

“Conscientious theater managers currently saddled with Mitchell have two humane choices to offer their perspective patrons: (1) earnestly plead with them that they’d be better off at another movie, or (2) offer some complimentary No-Doz,” bemoaned Paul Beutel (The Austin American Statesman, June 23, 1975). “Mitchell is a superb exercise in tedium, void of any and all elements for which we go to see a movie. Good action and performances? An interesting story? Snappy dialogue? Forget it. And Baker ambles through his part with a certain air of non-commitment.”

And it only gets worse from there: “Okay, all you Joe Don Baker fans. All three of you, that is. Your hero is back in a film called Speedtrap,” chided Bob Keaton (The Fort Lauderdale News, April 19, 1978), who also took potshots at the actor's expanding waistline. “The screenwriters couldn’t quite decide whether they wanted to have a car chase comedy, a crime caper, a story of police corruption, or a routine whodunit car robbery story, so they’ve given us parts of all. But these parts don’t add up to a whole lot.”

Part of the problem might’ve been oversaturation -- with five overlapping films nearly hitting theaters all at once, or people’s perception that Baker only had one acting gear: surly -- something I don’t agree with, and neither did Baker while commenting on the “two stages of his career thus far” to Jerry Buck (The Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 11, 1978).

“I used to play the bad guy who went around beating heads,” said Baker. “Now I play the good guy who goes around beating heads. They’ve got me pegged as a gentle man who gets involved in violent situations. I don’t like it. I’d really like to play a human being for a change. They shove you into a pigeon hole out here (in Hollywood). They say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s what he does.’ I didn’t study acting all those years in New York to be typecast. I don’t want to do the ‘hit and run’ films anymore.”

This kind of typecasting would explain Baker’s “non-committal” performances in some of these roles. But, c’mon. Let's be honest. Baker was born to play the role of Buford Pusser, who struck a chord with audiences and helped ease the country out of its post-Vietnam and post-Nixon malaise. His characters were antiheroes, who bucked the establishment, joining the likes of Harry Callahan, Billy Jack, Paul Kersey and Frank Bullitt.

He was also a nice contrast to all the Ken Dolls Hollywood was trying so hard to sell in the 1970s -- your James Olsons or Monte Markams, but then they kinda found the middle-ground with the likes of Robert Redford and Jeff Bridges and Baker never stood a chance after that no matter how good the acting chops.

He tried to keep it going, headlining a few more genre films like Checkered Flag or Crash (1977), The Pack (1977) -- “Those dogs were some of the best actors I’ve ever worked with,” Baker told Buck, or Wishbone Cutter (alias The Shadow of Chikara, 1977), a film where all signs point to it being a Joe Don Baker versus a Bigfoot movie, only it isn’t and is much, much more stranger than that. And then found a temporary refuge on television, headlining the series Eischied (1979-1980), which deserved a few more seasons to stretch its legs with its backroom political intrigue wrapped around the homicide investigation of the week.

And as he entered the 1980s, Baker transitioned from leading man to being a character actor, basically playing parodies of himself in most cases in films like Wacko (1982), Joysticks (1983) and Fletch (1985). He would also latch onto the James Bond franchise, playing the villain in The Living Daylights (1987) and later played Felix Leiter’s replacement, Jack Wade, in GoldenEye (1995) and Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), serving as 007’s CIA contact.

Sadly, Baker would become a bit of a cinematic punching bag after Mitchell was pasted on an episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000 (S5.E12, 1993). The episode is hysterical, one of the show’s best, which portrayed Baker as a drunken, slobbish lout of the highest order and triggered a running feud between the actor and the show. But I do encourage those who’ve only seen this version of the film to give the original, unfiltered version a go at least once to get the whole picture. (If nothing else, you’ll at long last find out what happened to John Saxon.)

And for a time, films like Framed became known as Mitchell Goes to Jail, Speedtrap begat Mitchell Goes Vroom, and Final Justice (1985), which also earned the MST3k treatment (S10.E07, 1999), was known as Mitchell Goes to Malta. A fate Baker didn’t really deserve but might’ve had coming.

But underneath all that perceived bumpkin buffoonery was a simmering powder keg just waiting to explode, a brute that could dish out as much damage as he takes on. Plug that into the revolving plots, where his characters were always wronged in some way, who then swear bloody revenge, who then gets beat up a few more times, throw in a car chase, and then wrap it up, fast and neat, when Baker kills everybody and, well, that pretty much sums up his career. Fair assessment? Probably not, but it sticks.

Framed was no different. Here, Briskin sets up a pretty decent conspiracy to unravel but then the film seems complacent to just idle along at a slow boil until some pertinent information shows up in the last reel that ties in with what happened in the first. Lewis seems hellbent on wanting to find out who set him up, and is equally hellbent on kicking their asses when the time comes, but then does nothing, really, as all the info conveniently finds its way to him via Vince, Sal, or Perry.

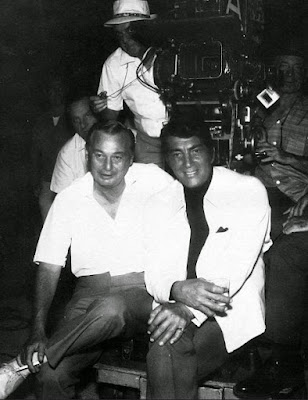

Phil Karlson and Dean Martin (The Silencers, 1966).

Framed would also be a career capper for Karlson. Said Mahon (1974), “A toiler in the B‐picture salt mines for a quarter of a century, Karlson has up to now meant little in the film industry, despite an on‐again, off-again underground cult and the support of a few critics, like Andrew Sarris and Bosley Crowther. Now, at 65, the age at which most film directors are prepared to hang up their hats and call it quits, Karlson is besieged by offers to make new violent pictures, receives pages of praise from Pauline Kael in The New Yorker, and is -- with a small piece of the Walking Tall action he won't exactly specify -- going to be very, very rich.”

None of those films mentioned by Mahon ever materialized. And like Pusser, the director would get an undisclosed piece of the Walking Tall box-office pie, which also made its broadcast debut in 1975, opening up a whole new revenue stream on his percentage. Thus, set for life, Karlson retired from filmmaking but would start teaching film courses.

In retrospect, when McCarthy asked Karlson about the differences between working at Monogram and the bigger studios like Universal or Columbia or Paramount, assuming it had to be better with all the perks, his answer may come as a surprise.

“No! It was a lot nicer working for the smaller studio because there wasn't any committee to worry about. When they gave it to you, you were in charge. You did it. Nobody told you what to do. They couldn't afford all these guys to come in and discuss things -- ‘Let’s get together, let's discuss it.’ You work in a big studio, there's an assistant producer, a producer, then there's an executive producer, then all the way up to the head of the studio,” said Karlson.

Karlson and Sharon Tate (The Wrecking Crew, 1968).

“No, there was actually more freedom -- of course, so fast! -- in the smaller studios. Really, it was the greatest teacher in the world for me, because I could experiment with so many things doing these pictures. No matter what I did in the smaller studios, they thought it was fantastic, because nobody could make the pictures as fast as I could at that time, and get some quality into it by giving it a little screwier camera angle or something.”

Even when working in the B-Units of the A-Studios was a pain. “In the B-echelon, they had the same bunch of guys right down the line. They had the guy who thought he was the president of the company, who was the head of the B-unit. Then he had his assistant right down the line.”

Working for BCP, Karlson had a lot of freedom on Walking Tall; and due to that film’s financial success he would also be given a lot of rope on Framed, too. And after watching it and Walking Tall again for this write-up, I think Walking Tall is the better film but Framed has aged better. Unlike Walking Tall, which has stayed on a pretty even keel over the years, Framed has gotten exponentially better with each viewing. Baker is rock solid when you plug him into his comfort zone, and he’s ably abetted by Dell, Marley and Van Dyke. And so, as last efforts go, eh, it could’ve been worse.

Thus, with a career that was marked with tragedy and missed opportunities, Karlson’s one big hit came late in his career. Too late? Perhaps. In the end, I’m not really sure why Karlson isn’t remembered as well as his contemporaries like Don Siegel, Samuel Fuller, or Robert Aldrich.

I have suspicions, given the tenor of his politics and the leftist bent in his early films, while not ever mentioned when it came to the Hollywood Blacklist, that it was possible Karlson wound up on the unofficial Greylist, with the likes of cinematographer Floyd Crosby and composer Elmer Bernstein, which might explain his falling out with Cohn and why he never got a shot at a bona fide A-picture and left to toil on the B-lots. Again, this is just conjecture.

Still, as others have pointed out, the director and his body of work does have a small but very vocal fan base, who do their damndest to shed some light on his work. And if the length of this write-up wasn’t a big enough clue, I do belong to that cantankerous Karlson’s fan base. And I hope this sprawling after-action report has shed some light on it for you, too.

Originally published on January 20, 2001, at 3B Theater.

Framed (1975): Paramount Pictures / P: Mort Briskin, Joel Briskin / D: Phil Karlson / W: Mort Briskin, Art Powers (Novel), Mike Misenheimer (Novel) / C: Jack A. Marta / E: Harry Gerstad / M: Patrick Williams / S: Joe Don Baker, Conny Van Dyke, Gabriel Dell, John Marley, Brock Peters, Warren J. Kemmerling, John Larch, Paul Mantee, Walter Brooke, Roy Jenson

No comments:

Post a Comment