We begin with a disaster already in progress. Apparently, Dr. Paul Wilson’s repeated attempts to send a space-probe to the planet Venus haven't been going very well. In fact, if we wanted to be brutally honest about it, they've been a total cluster-[expletive deleted].

But not one to give up so easily, even though all the previously launched satellites malfunctioned and cracked-up somewhere in orbit, another $9,000,000 probe has been launched. (Hell, it’s only the taxpayer’s money. Why not.)

Meanwhile, in Washington DC, at the Pentagon, an impassioned Tom Anderson implores to the head brass of such things that this latest effort to reach Venus will also end in failure. In fact, all attempts to explore outer-space must be aborted immediately. As to why, well, get this:

Once considered a brilliant scientist -- and an important cog of Wilson's Venus probe program, Anderson (Van Cleef) has apparently gone off the deep end. See. He is now unemployed and a couple of cans short of mentally stable six-pack, ever since he started claiming to be in direct communication with certain extraterrestrials, who choose to remain anonymous at this time.

Thus, it should really come to no one's surprise that Anderson's repeated warnings about his ‘alien friend’ putting up a NO TRESPASSING sign anywhere outside Earth’s stratosphere, and how all further interplanetary probes will meet with the same fiery fate, aren’t being taken all that seriously.

Now, despite his former colleague's shaky mental state, Wilson (Graves) remains close friends with Anderson and his wife, Claire. It's been three months since the latest launch and everything has been progressing smoothly. But when the Andersons invite the Wilsons over for dinner, despite Claire's protests, her husband plans to reveal his alien communication equipment to his guests after dessert. Thus, try as she might to talk him out of this, with her husband deaf, blind and dumb in his obsessions, all Claire (Garland) can do is woefully shake her head and prepare for the evening.

Later, after Wilson and his wife, Joan (Fraser), arrive, and the ladies excuse themselves to the kitchen, Anderson makes his big reveal and smugly confides to his friend about how he has been in communication with an inhabitant of the planet Venus for quite some time now; and being in constant contact with this friend from another world, Anderson has completely bought into the Venusian's way of life, which, according to him, is far superior to what is found on Earth.

Now, all Wilson can hear over the transmitter is static despite his friend's assurances that it's not feedback but the Venusian communicating with them. Unsure of what to make of all of this, he also doesn't have long to contemplate this conundrum before receiving an urgent phone call from the Space Probe Command Center. Sure enough, just as Anderson had predicted, the latest Venus probe has finally disappeared, too.

After the Wilsons leave, Claire lets her gloating husband know their current situation has made her very uncomfortable. She still loves him, but his wife is at her wit's end with all this ‘alien dogma’ talk and just wants her old husband back.

Told not to worry, Claire is promised big things are in the works for the both of them. How, you ask? Well, he says, she'll just have to wait a little while longer, then, all will be revealed. But it's going to be wonderful, he assures. Wonderful for the whole world.

Meanwhile, over at the Command Center, Wilson is informed his latest probe has fortuitously reappeared on radar as it returns to Earth. All seems nominal at first with the telemetry as the command crew tries to guide it safely back down -- but they quickly lose control again, and then helplessly watch as it radically veers off course and, presumably, crashes.

This is confirmed by an extremely funny FX shot of the Flying Saucer-inspired probe gently gliding down, but then quickly accelerating at a 90-degree angle straight into a cliff, where it promptly explodes! (You half expected it to peel off just like Wile E. Coyote once the smoke cleared.)

But upon closer examination, emerging from the smoldering wreckage, something sinister scuttles out, an inhuman stowaway, that’s hellbent on interplanetary conquest…

As a filmmaker, Roger Corman was just getting started in 1955. After completing his initial three picture handshake contract for Jim Nicholson, Sam Arkoff, and their newly minted American Releasing Corp., with the general release of their opening salvo, The Fast and the Furious (1954), Five Guns West (1955), and The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), alas, it appeared things might be all over already before it ever even had a chance to begin.

At the time, ARC had three production units rolling film: Corman’s Palo Alto Productions, Alex Gordon’s Golden State Production, and a sub-contract with Dan and Jack Milner, a couple of former film editors turned producer / directors, known colloquially as Milner Brothers Productions. The problem was, they weren’t really making enough money on the films these guys finished.

The St. Louis Dispatch (October 10, 1954).

The gist of said problem was that they could only get their pictures booked into theaters as the bottom bill of a double feature. “In those days the top half of a double-feature package always got the lion’s share of ticket sales,” said Randy Palmer (Paul Blaisdell: Monster Maker, 1997). “All Nicholson and Arkoff could hope for was a standard flat weekly rate of $100, $200, or, if they were really lucky, perhaps as much as $300. To get better payoffs than that, ARC would have to supply their own tailor-made double features.”

Thus, Corman’s follow-up feature, Apache Woman (1955), another Western, would be one of the last films ARC would release on its own. After that, his next feature, a startling tale of Science Fiction, would serve as one-half of ARC’s first ever combination double-bill.

A parable of racial bias, Apache Woman sees government agent Rex Moffet (Lloyd Bridges) sent to Arizona to investigate a series of deadly robberies plaguing a small mining town. And while all evidence points to the perpetrators being some Apaches from the local reservation, Moffet isn’t so sure.

While investigating, he falls in love with Anne (Joan Taylor), a half-breed, who eventually uncovers the truth (it was her white step-brother all along), which ends in a shoot-out where Dick Miller, making his screen debut, nearly shot himself on screen playing a cowboy and an Indian on opposite sides of the climactic shootout.

(L to R) Joan Taylor, Lloyd Bridges, Roger Corman.

“We shot the picture at Iverson’s Ranch, where many many westerns had been shot. It was located at the far end of the San Fernando Valley. It combined a lot of rock formations with several meadows, so in a very close proximity you were able to get a variety of backgrounds,” said Corman. (Trailers from Hell, Apache Woman, January 14, 2014).

“The film was very interesting to me because I was working with a script by Lou Rusoff, who was sort of the contract writer for [American Releasing]. I generally worked from scripts I had developed myself, and it was interesting to take somebody else's idea and try to bring them to life.”

As for his follow up feature, we move to the far flung future of 1970 and the Day the World Ended (1955) -- another exploitable title cooked up by ARC front man Nicholson. Said Arkoff, “Day the World Ended was shot in ten days (in living SuperScope!) at a cost of $96,000. Roger directed it, and it capitalized on America’s heightened anxiety over nuclear war, and coincided with a growing epidemic of Americans building bomb shelters in their backyards.” (Flying through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants, 1993).

Essentially putting all of their Palo Alto and Golden State eggs in one basket, Alex Gordon would produce the film and handle the casting, while Corman would direct and handle just about everything else.

The script was also written by the ex-pat Canadian Rusoff, Sam Arkoff’s

brother-in-law, who would go on to write a ton of pictures for the

company, from Runaway Daughters (1956) to Hot Rod Gang (1958) to the

inaugural Beach Party (1963), until his untimely death in 1963.

Technically set the day after the world ended (-- because it’s cheaper to tell you about a nuclear apocalypse than it was to show it), the ‘tempest without / crisis within’ grist of our story focuses on a group of seven disparate survivors who find refuge from the deadly fallout in an isolated valley. And while they struggle and mostly fail to get along on the inside, on the outside they are menaced by a deadly irradiated mutant -- a mutant with a startling secret.

“This was an idea reworked to fit a low budget,” noted Corman in his autobiography, How I made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (1990). And to save money, “I tried to make it something of a psychological study of a small group of people thrown together under unusual circumstances.”

Corman expanded on these notions further for J. Philip di Franco (The Films of Roger Corman, 1978), saying, “The story dealt with the after-effects of an atomic war and the concept of starting life anew -- whether man can shape his destiny or is driven by irrational forces within. I have always believed it is essential to find a unifying idea or theme to work with; otherwise, a picture lacks meaningful impact, no matter how much action and special effects there may be on screen.”

Still, it was the monster on the poster that usually drew in the crowds for Corman’s lessons in civics and philosophy. The radiation scarred, tri-eyed Mutant was provided by Paul Blaisdell, who, you remember, bailed out Corman and ARC on Beast with a Million Eyes. Said Arkoff, “Paul was short in stature (five-foot-two, 120 pounds), but seemed to rise to just about any challenge we gave him.” (Arkoff, 1993.)

This time, instead of a puppet, Blaisdell would build a full-size costume to fit him -- and not the stuntman they hired. (On purpose? You bet). And for the record, Blaisdell actually measured in at five-foot-six -- the exact same height as his leading lady, Lori Nelson.

Marty the Mutant (alias Paul Blaisdell).

Shabby at first glance, you have to remember that most of Blaisdell’s creations had a patchwork origin. With his limited budgets and time constraints, he couldn’t make casts or molds for a full rubber suit. Instead, he pieced his suits together with chunks of carpet padding, foam rubber, and cured liquid latex scales, with claws and teeth whittled from white pine.

Starting with a pair of long-johns, each of these pieces were cut to spec and then glued on individually -- a fastidiously slow process. When the suit was completed, it would then be meticulously painted to bring out the details, which hold up remarkably upon further inspection, including the vestigial, lobster claw-like protrusions jutting from the Mutant’s shoulders.

(L to R) Lori Nelson, Marty the Mutant, Roger Corman.

The film was mostly shot on the grounds of the Sportman’s Lodge, a famous restaurant also located in the San Fernando Valley, where patrons could catch fish from their pond near a waterfall and have them fry it up to eat. And while Alex Gordon recalled no real mishaps during filming, he must have forgotten the moment when Blaisdell nearly died.

Apparently, when it comes time for the Mutant to meet its doom by disintegrating in a torrential freshwater rainstorm, I'll pause to remind everyone of the suit's patchwork and foam origins (-- yeah, basically a giant sponge). When the rains came on cue, and the creature collapsed to the ground, at first Blaisdell was happy and felt great under the cooling water after a hot day of filming; but this quickly gave way to panic.

See, to add to the disintegration effect, a tube was attached to the costume to pump in some smoke that would then seep out of the seams -- but not fast enough, apparently. So! Not only was the suit getting saturated with water, it was also filling up with noxious fumes!

When Corman finally yelled ‘cut’ and hurriedly moved on to film the next scene, someone realized their monster hadn't gotten up yet. The carpet-foam suit had soaked up too much water and Blaisdell, who realized he was slowly drowning on dry land and asphyxiating, whichever came first, really started to panic, because he couldn’t get up since the suit was now too heavy!

Luckily, he was rescued in time; and when they stood him up, all the accumulated water comically gushed back out the way it had come in through his lower extremities. (There were plenty more production tales but I think we’ll save those in case we ever get around to actually reviewing the film they belong to. No. No. This was just an aside.)

Since ARC couldn’t afford to make a second Science Fiction feature on their own, the plan was to pair Day the World Ended with Phantom from 10,000 Leagues (1955) for ARC’s inaugural double feature.

Thus, Phantom was a pickup. It was shot by the Milner Brothers and financed through a consortium of Japanese-American investors, who raised $75,000. And while they did share the same screenwriter in Rusoff, Blaisdell turned down their low-ball offer to make another monster -- an irradiated sea creature this time. (If memory serves, it was supposed to be a mutated turtle.)

Meanwhile, Nicholson and Albert “Al” Kallis, the in-house artist for ARC, were cooking up the films’ posters and promotional campaigns. “Kallis and Nicholson worked well together,” said Mark Thomas McGee (Fast and Furious: the Story of American International Pictures, 1984). “They shared a belief that motion picture advertising had to create a ‘must see’ feeling in the buyer. A sense of urgency.”

Albert "Al" Kallis.

In an interview with Stephen Rebello for Cinemafantastique (March, 1988), Kallis added that “at [ARC] advertising always came first. What was important was the thrust, the sense of what you were selling and how it would appeal. Invariably, I never saw a picture before I did the ad campaign. And Jim Nicholson had the best sense of exploitation I ever encountered in a distributor.”

As for his design skills, “Our problem was to make the artwork leap off the newspaper page or poster, to create that compelling sense, ‘I’ve gotta see it now!’”

The Los Angeles Times (January 6, 1956).

Nicholson, meanwhile, stamped all kinds of hyperbole over Kallis’ extremely effective efforts, calling it an “All New-All Time Shock Show!” that promised “A New High in Naked Screen Terror!” and “Human emotions stripped raw! The terrifying story that COULD COME TRUE!” And these newspaper ads were emblazoned with five SEE! snipes. SEE! The World Ended in Atomic Fury! SEE! The Horrible Mutant Who Seeks a Mate! SEE! The Terrifying Beast on the Ocean Floor! SEE! The Battle for Life at the Bottom of the Sea! And my personal favorite, SEE! Fantastic World of Death and Horror!

Since ARC put up more money and was taking more risks on the distribution end of this Sci-Fi double-bill, both sides agreed to a 60-40 split on the profits. The problem was, they couldn’t get any theaters to book them as a combo.

“From the beginning, we had to battle for bookings in a lot of cities,” said Arkoff (1993). “Exhibitors everywhere told us they wanted to split up the movies and turn them into second features.” But Nicholson and Arkoff stood their ground, demanding they either show them as a combination or don’t show them at all. And not only that, they were demanding the same rental rate as the major studios. A strategy that nearly backfired on them.

“The pictures were released in September (1955), but by December we had no theater dates. The exhibitors were [that] stubborn,” said Arkoff. “Finally, a quirk of fate got us off the launching pad. A newspaper strike hit Detroit, and as a result, the major studios didn’t want to release their movies without newspaper advertising to support them. (This was before the era of TV advertising movies.) With exhibitors [now] desperate for features, we jumped at the opportunity.”

They managed to get the double-bill booked for the week leading up to Christmas in Detroit's mammoth Fox Theater, which could seat over 5000 people. Then, scrounging up what they could for an all-out publicity blitz, since advertising in the newspapers was out, ARC organized a leaflet drop and a mini-parade, according to Arkoff. “Our so-called ‘horror caravans’ with scenes from the movies recreated on flatbed trucks, complete with monsters menacing scantily clad women, and lightly clad men trying to protect the women by fending off the beasts.” (And given the temperature of the season, I hope these extras got some hazard pay.)

Odds are good that the original Mutant costume was part of that ‘horror caravan’, too. “To drum up publicity for the film, Arkoff and Nicholson thought it would be a neat idea to send Marty the Mutant out on a press tour,” said Palmer (1997). “Theaters that were running ARC’s first double-feature were shipped the costume for display. Most theater managers set up Marty in their lobby, where curious ticket-buyers reached out to wiggle the antennae and tug at the scales, dislodging them by the fistful.”

Marty the Mutant and Lori Nelson.

Said Blaisdell (Palmer, 1997), “Marty was shipped all over the U.S. He’d get damaged and they’d ship him back to me and I’d repair him, repack him, and reship him.” This would be repeated several times until the initial theatrical run petered out. But, “After that, nobody could ever figure out where Marty finally ended up.”

Thus, it was never returned and Marty the Mutant’s ultimate fate remains unknown, mostly an unmarked grave in an anonymous landfill. (This also might explain why a proposed sequel never materialized.) Would this sacrifice be worth it?

The Pomona Progress Bulletin (December 31, 1955).

“The hard work paid off,” said Arkoff. “The combination was a surprise hit in Detroit, and overnight, that encouraged exhibitors in other cities to book us, too. Dates materialized in Los Angeles and New York. Then in Chicago, Boston and Dallas. We were off and running.”

In Los Angeles the combination played so well it was held over four weeks. In the first week alone, it grossed $140,000. Here, the Milners got a harsh lesson in studio economics on their return, but they did get their money back -- eventually.

However, their story kind of ends with the release of their next feature, From

Hell it Came (1957), where a sentient tree-stump galumphs around and

terrorizes a South Sea island (-- a monster based on Blaisdell's design that he never got paid for). A film so talky, and so inert, even ARC wouldn’t

release it.

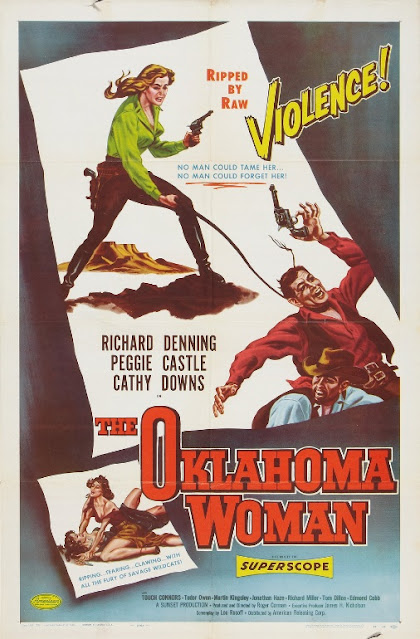

But Corman was on board for one half of the next combination, another Western with The Oklahoma Woman (1956). Here, Rusoff’s plot revolved around a returning gunslinger (Richard Denning) getting framed for murder by his jilted ex-lover (Peggie Castle). Luckily for him, his new girlfriend (Cathy Downs) exposes the real murderers before he gets lynched. The only real snag in the production was a cat-fight between Castle and Downs on who would get top-billing below Denning. Castle would win out but Downs would sign a three picture deal with ARC as a consolation prize.

“The Oklahoma Woman cost about $60,000,” said Corman (1990). “I tried to create a bigger look than the budget might indicate and save time and money in the process. I experimented, for example, with shooting consecutively all the components of multiple scenes that faced in one direction in the saloon, though they were, obviously, way out of sequence. I could light one time for many set-ups. Then I reversed the angle and shot the components of multiple scenes that faced in the opposite direction.”

But this analytical approach, while economical, didn’t really pan out. Said Corman, “I found that to be, perhaps, an overly effective way to work. Matching backgrounds and wardrobe -- which I did from memory in the pre-Polaroid days -- is much easier than ripping down all your lighting and relighting. But it was too difficult for the actors and since then I’ve tended to shoot more in sequence.”

The Oklahoma Woman would be paired with Female Jungle (1956), another pick up; this time courtesy of Burt Keiser, which required a lot of dust removal because no one else would touch it until Kaiser sold it off cheap to ARC -- and glad to be rid of it, too, due to its dodgy production history.

See, Female Jungle was the feature debut of Jayne Mansfield, then a complete unknown. It also marked the return of Lawrence Tierney, a film noir icon -- Born to Kill (1947), The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), The Hoodlum (1951), who, according to Arthur Lyons (Death on the Cheap, 2000), after several “off-screen bar brawls and numerous arrests during the 1940s,” was “persona non grata in Hollywood.”

According to McGee, Mansfield got the part because her agent asked for $50 less than the other starlet up for her part. But the only reason Mansfield wound up as the de facto lead was because the original lead actress, Kathleen Crowley, was attacked and sexually assaulted while en route to a location for the day’s filming.

At that time, only half of the film had been shot. And so, Keiser and Bruno VeSoto, the film’s director, scrambled to get the script rewritten to bring Mansfield’s character to the forefront, while a mismatched stand-in was used to fill in for the traumatized Crowley. As the legend goes, once filming wrapped, Mansfield went back to selling popcorn at a movie theater.

But luck was once again on ARC's side with yet another quirk of fate. As not long after Keiser dumped Female Jungle on them, Mansfield was officially discovered and starred in the Broadway production of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter, where her wardrobe mostly consisted of a bath towel; and then her career took off like a rocket after her appearance in Frank Tashlin’s The Girl Can’t Help It (1956), and the country would never look at a milk bottle the same way ever again.

ARC would cash-in on this free publicity for their “2 All New Shockers!” featuring “Broadway’s Boldest vs. the West’s Wildest!” These Mansfield-centric ads screamed “Thrills Jolt with the World’s Most Publicized Personality!” And how Time Magazine referred to Mansfield as “Sex on the Rocks.”

The Los Angeles Times (June 22, 1956).

But there was also plenty of room for Nicholson to bring his A-Game. “Excitement Screams with the Burst of Gunfire!” And “Ripped by Raw Violence! No Man Could Tame Her! No Man Could Forget Her!” “Ripping! Tearing! Clawing! With all the Fury of Savage Wildcats!” *whew* How could ARC lose! They couldn’t. And they didn’t. And with another bona fide smash hit on their hands, ARC was thinking big for the rest of 1956.

In fact, these packages were so successful ARC would pair up their former bottom bills and send them back out as combos in ‘56, like the “Screaming Terror!” and “Naked Violence” of The Beast With a Million Eyes and Apache Woman, “A Double Bill of Thrills!”

Corman, meanwhile, began the new year with a little side-hustling, shooting Swamp Women (1956) for the Woolner Brothers, Lawrence and David, who owned a string of drive-in theaters in the south, ranging from New Orleans to Memphis.

The film revolved around an undercover sting operation, where a police woman (Carole Mathews) poses as a prisoner to instigate an orchestrated jailbreak as part of a slightly convoluted plan to recover a cache of stolen diamonds hidden somewhere in a backwater bayou. The officer escapes with three other prisoners (Marie Windsor, Beverly Garland, Jill Jarmyn), they take a hostage (Mike Connors), find the diamonds, backs are stabbed, crosses are doubled, and the ringleader nearly escapes before they’re all caught.

“Swamp Women was a little picture that was a lot of fun,” said Corman (Franco, 1978). It was with this film that I developed a crew that became known as ‘the Corman Crew’: Floyd Crosby, the cameraman; Chuck Anawalt, the key grip; Dick Rubin, the soundman, and a number of other people who worked with me on picture after picture. We all got along together. One of the reasons I was able to make so many pictures so inexpensively and so quick is that we all worked very well together, so much so that when I would not be shooting, people would hire my entire crew.”

Later, the Woolner’s would produce Attack of the 50ft Woman (1958) for Allied Artists, but are probably better remembered for a string of Italian co-productions with Mario Bava, including Hercules in the Haunted World (alias Ercole al centro della terra, 1961) and Blood and Black Lace (alias Sei donne per l'assassino, 1965), one of my favorite films (Murder Bongos!), and Antonio Margheriti’s Castle of Blood (alias Danza Macabra, 1964).

His next assignment for ARC would be Corman’s fourth and last female-centric Western, Gunslinger (1956) -- in fact, it would be Corman’s last Western period. And it’s easy to understand why as this latest production was a complete disaster from the jump.

It began when Corman took Charles “Chuck” Griffith, a novice screenwriter he’d taken a shine to, to see a Randolph Scott western. When the end credits rolled, Corman told him to write the same picture but make the sheriff a girl. Given the time frame and plot, odds are good the film they watched was A Lawless Street (1955).

According to McGee (1984), “The picture was scheduled to begin in March. Then word reached Roger that the unions were about to shorten the six day workweek to five with no decrease in salary. He hurried into production in February to beat the deadline,” said McGee. An economic decision that would soon come back to bite him in the ass.

“It rained the first day," reported McGee. "Some people I talked to said it never stopped raining. Equipment trucks drove into the mushy ground and sank axle deep. The cameraman couldn’t find a decent exposure.” And it was about to get worse from there -- much worse.

“Gunslinger was made around February 1956, just as IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) and the studios renegotiated for a five day work week instead of six,” said Corman (1990). “So I decided to squeeze in one last low-budget Western before the new contract went into effect. It rained five days out of six and it was the only time I ever went over schedule -- it took seven days. Trucks, heavy cameras, and lights sank in the knee-high mud. It was one of the worst experiences of my life!”

The consensus on the soggy set was that the film should’ve been rebranded as Mudslinger. “The shoot was rough on everyone,” said Corman. “Allison Hayes, a very witty, humorous actress, came up with the best line of all. ‘Tell me, Roger,’ she said, soaking wet and cold, ‘who do I have to f@ck to get off this picture?’”

Well, Hayes didn’t have to have sex with anybody to get off the picture. No, she only had to break her arm in a stunt gone awry (-- by design or by accident, depending on who is telling the tale). Hayes played the villainess of the piece and the heroine sheriff was played by Beverly Garland, who had worked with Corman on Swamp Women.

“I always wondered if Allison broke her arm just to get off the picture and get out of the rain,” said Garland (Corman, 1990). “It poured constantly. But what I adored about Roger was he never said, ‘This can’t be done.’ Pouring rain, trudging through the mud and heat, getting ptomaine poisoning, sick as a dog -- didn’t matter. Never say die. Never say can’t. Never say quit. I learned to be a trooper with Roger.”

Now, one of the reasons Hayes got hurt was because Corman hardly ever hired stunt doubles. Said Garland, “Riding, stunts, fights -- we did it all ourselves and we all expected it in these low-budget films.” But Garland would not escape Gunslinger unscathed either, twisting her ankle badly on a botched mounting stunt, where she sailed over the horse instead of landing in the saddle. It was swollen so badly they had to shoot it up with Novocaine to film the climactic brawl, and at the end of the final day, her boot had to be cut off because it wasn’t coming off on its own.

ARC would strike a deal with the Woolners and would pair up Gunslinger with Swamp Women for a “Deadlier Than the Male!” two-punch combo with "Scarlet Women Out to Get Every Thrill They Could Steal!" that "Strips Down to Naked Fury!" Said the Los Angeles Times (October 26, 1956), “The quality of mercy, wrote Shakespeare, is not strained. Since the Bard never saw Swamp Women or Gunslinger, it’s possible to see how he could feel that way. These films take one’s credulity firmly by the neck, shake it, twist it, stretch it, and finally bend it double before the action, such as it is, ends.”

The Los Angeles Times (October 26, 1956).

The Omaha World Herald (June 26, 1956).

Gunslinger is the only Corman Western I’ve ever seen. But despite some solid performances by Garland and John Ireland, I found the film tedious and needling toward boring. And because of that, it’s always made me shy away from checking out the other three. From what I’ve dug up, they’re all cheap but serviceable, with the general consensus being The Oklahoma Woman was the best of these early efforts in sagebrush and tumbleweeds.

Now, this double feature, along with the “Double Sock! Rock! And Thrill Show!” of Hot-Rod Girl (1956), another pickup, where “Teenage Terrorists Go on a Speed-Crazy Rampage,” and Girls in Prison (1956), featuring the “The True Story of Girls Behind Bars -- Without Men!”, would be the very last combo for ARC. But fear not.

Omaha World Herald (September 14, 1956).

Nicholson and Arkoff had always wanted to brand themselves as American International Pictures from the beginning but someone had apparently beaten them to it -- another company had a claim on American Pictures, whose sole release as far as I could determine was Albert Zugsmith’s Invasion U.S.A. (1952). And when that company folded, as of March, 1956, ARC officially became AIP and American Releasing officially ceased to exist.

Here, emboldened by these recent successes, Nicholson announced that American International would market 90 films over the next three years: 20 releases for 1956-1957, then 30 for 1958, and 40 for 1959. Said Nicholson (Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, July 18, 1956), “There’s nothing wrong with the motion picture industry that good pictures made at common sense costs won’t cure.”

And to inaugurate this name change, they commissioned their biggest double-bill to date. There would be no pick-ups this time. They would be producing both pictures in house for an “All New Monster vs. Monster!” showcase with “Two Top Science-Horror Shows on One Program!”

Handling half of that equation would be Alex Gordon and director Eddie L. Cahn, who would tackle the production of The She-Creature (1956), a tale inspired by the Bridey Murphy craze on past-life regression (-- and another production story for another day). As for its sparring partner, Corman would take on the challenge of Venusian invaders with It Conquered the World (1956).

(L to R) Lou Rusoff, Marty the Mutant, Alex Gordon.

Both features would feature outlandish monsters created by Blaisdell, as only he could cook them up; and once again both were to be written by Rusoff -- only this time, his head wasn’t really in it due to personal issues.

“Lou Rusoff was rather a strange man,” said Alex Gordon in an interview with Tom Weaver (Science Fiction Confidential, 2002). “He was a very moody person, and you never knew whether he was gonna be in a good mood or a not-so-good mood. If things weren’t going right, he would worry about it and he’d kinda go off and brood about it -- things like that." As for the calls of nepotism: "He was in the business long before Sam Arkoff, and he was a fairly successful writer of radio shows. He pretty much put in [each script] what he thought should be in there, and all the ‘ingredients’ Nicholson wanted in there,” said Gordon.

“Rusoff had written a script that was incomprehensible, which was quite strange ‘cause he was quite meticulous,” Griffith told McGee in an interview for Fangoria Magazine (No. 11, October, 1981). Apparently, “Lou’s brother was dying at the time, which most likely had something to do with it.”

As for pitching in on It Conquered the World, “That was my first script to get made,” said Griffith (Senses of Cinema, April 15, 2005). “The original writer was a cousin or brother-in-law -- I forget which -- of Sam Arkoff. He had written an incoherent script and left for Canada because his brother had died. I was brought in to fix it up in a couple of days. I got into the habit of writing very quickly without realizing it and, because I was raised in a radio family, I didn’t know that you were supposed to take a long time to write a film script.”

Griffith’s first original screenplay was for Gunslinger, which was co-authored by his friend, Mark Hanna. And we’ll be taking a closer look at the life and times of Chuck Griffith in our next update, so stay tuned. For now, he was given Rusoff’s script late on a Friday and he had to have it ready to shoot when the camera’s rolled the following Monday morning.

“Griffith was given just 48 hours to write something they could shoot,” said McGee (1984). “He wrote streams of dialogue without looking at Rusoff’s script again. He knew Roger didn’t have the money to show anything. (And so, he concluded), the picture would, in essence, be one end of a radio conversation.”

And I don't think Griffith meant that this was between the characters on film listening to the glorified ham radio, but literally meant it as between the film and the audience in general -- the film is the transmitter and the audience is the receiver, which brings us into dangerous levels of telling and not showing.

Said Corman (Franco, 1978), “The basic idea for this was the invasion of Earth by an alien force. The creature came from a planet much larger than Earth. Since I had majored in engineering, with a minor in physics, I set about designing the creature according to scientific principles. To function on a planet with heavy gravity, life forms would have to be very massive and low to the ground; the creature was designed to match these specifications.”

James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff.

Both Nicholson and Blaisdell would sit in on these brainstorming sessions to realize their alien invader. Said Palmer (1997), “Nicholson wanted something that no one had ever seen before, something that was really different.”

Said Blaisdell (Palmer, 1997), “[The script called] for some kind of creature that was pretty invulnerable and came from the planet Venus. At that time the belief about the physiognomy of Venus was that it was hot, humid, conducive to plant life but not too well suited to animal life. If anybody would care to think it out, there is a kind of vegetation we have right here on Earth that you wouldn’t particularly feel like fooling around with. Not a carrot or an ear of corn, but something that grows in the darkness and the dampness, something that might grow on the planet Venus. Something that might, in lieu of animal life, develop an intelligence of its own. It would move like a perambulatory plant, but it would not move very far. When it wanted to conduct direct action, it would send out small creatures which it would give birth to, and they would do its dirty work.”

From Randy Palmer's Paul Blaisdell: Monster Maker.

Blaisdell then concocted a 10-inch proof of concept model, and then stuck it in a diorama of his hyper-intelligent mushroom laying waste to a squad of plastic army men. Nicholson was delighted. Corman approved. And Blaisdell went to work to bring his malevolent Venusian fungi and its minions to life. (More on his efforts in a bit.)

Casting the film caused a few headaches and was plagued by a string of last second replacements. But I think, in the end, It Conquered the World was improved upon and better served with these late substitutions.

The role of Paul Nelson was originally intended for Richard Boone but he proved unavailable. Peter Graves was no stranger to these types of low-budget Sci-Fi epics, having starred in Red Planet Mars (1952) and Killers from Space (1954), where he fought off an invasion of some bug-eyed aliens. Graves brings his usual earnestness and even keel, while Boone had a bad tendency to ham things up when he felt the material was beneath him.

Before he started showing up in Spaghetti Westerns -- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (alias Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, 1966) and Death Rides a Horse (alias Da uomo a uomo, 1967), Lee Van Cleef was usually cast as the heavy or showed up as the second or third henchmen on the left. He had recently delivered the killing shot to the defrosted dinosaur in Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), and would replace John Hudson as the misguided and duped Tom Anderson.

I’m unfamiliar with Hudson, but Van Cleef brings a nice grounded quality to the role of Tom Anderson and handles the science gobbledygook deftly as he’s forced to, as Griffith predicted, be the dummy in a one-sided radio conversation that only he could hear -- not the other characters nor the audience.

Meanwhile, Peggie Castle was originally cast to play Nelson’s wife but had to pull out due to other commitments. She would be replaced by Sally Fraser as a favor to Corman, a friend, even though she was five months pregnant. Knowing that in hindsight, it's fun to watch how they tried to hide the bump, so to speak. I supposed they could've just adjusted the script to have the couple be expecting their first child, but if they did, the tragedy that follows would most likely have never gotten past the censors. Yes, Fellow Programs, that's called ominous foreshadowing.

Thus, Beverly Garland was the lone survivor from the original casting sheet, who brings a lot of spark to Claire Anderson. It helps that she and Van Cleef have good chemistry; you believe that she believes her husband used to be a good man. And you also believe she would have the backbone and grit to win him back from the alien’s malignant influence no matter what the cost.

“Roger and I had a good working relationship, and we worked very well with each other,” Garland told Tom Weaver (Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers, 1999). “Roger had, and still has, a sense of what the public wants, and he was right there to supply those types of films. I think he made some of the best B movies around.”

(L to R) Jonathan Haze, Chuck Griffith, Dick Miller.

Also littering the cast were Corman regulars Jonathan Haze and Dick Miller. “Very often I wrote for the crowd around Roger’s office,” said Griffith (Senses of Cinema, 2005) “They were there all the time and we were all friends -- Dick Miller, Mel Welles and Jonathan Haze in particular. We’d be all in the pictures until Roger finally ended that process. It was becoming too obvious.” Here, even Griffith shows up in the film as one of the scientists at mission control.

Filming on It Conquered the World was set to begin on April 3, 1956. And it would proceed as scheduled thanks to Griffith, who managed to salvage the script in less than two days. Like the Randolph Scott Western, Griffith’s finished script was an obvious riff on Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), mashing up components of preventing self-destructive humans from screwing up the cosmos and flipping the off switch on all technology worldwide of the first film, with the paranoia and subversion of the hive mind, losing your free will, and being replaced by an unfeeling ‘pod person’ from the second.

This square peg was then forced through the round hole of an AIP budget with the Venusian’s arrival on Earth, having apparently hijacked and commandeered Nelson’s latest probe, and then rode it back! The Venusian then contacts Anderson, announcing its arrival. And during the course of their conversation, the alien promises that, together, they will take over this world for mankind’s own good and create a new utopian society.

But this will apparently have to be done in stages, starting with the space probe installation and the nearby town of Beechwood. Apparently, the alien invader can only produce eight organic "control devices" at a time before a week's recovery is needed before producing anymore.

Here, Anderson pulls a full-Benedict Arnold by revealing all the local authority figures who will have to be brought under control first before their plan can proceed any further. With that, the Venusian basically poops out several of these organic control implanting devices (-- resembling a genetic cross between a stingray and a maple-glazed cruller --) that flutter off to do their insidious deeds.

With phase one nearing completion, the alien then sets phase two into action by somehow shutting down all forms of energy in the immediate area, causing everything mechanical to slowly decelerate to a complete halt.

Here, the Wilsons get stranded in their car when the engine stalls out. They then witness a plane in distress that eventually crashes. When Paul asks Sally to note the time, she sees that her watch has stopped. At mission control, everyone is flummoxed by the sudden loss of power. Even the battery operated flashlights refuse to work, nor the hand-cranked generators.

Meanwhile, Claire Anderson picked the wrong day to go into town for some shopping, where the locals are starting to panic over this rolling blackout and then zero in on her. Her husband predicted this after all, so she must know something. That, or this was all his fault. But Tom comes to her rescue and whisks her away in their car. When asked how come their car works when everything else's doesn't, Tom says they've been omitted, and everything of theirs will still work, because they're collaborative allies of the Venusian.

Back on main street, Sheriff Shallert (Casey) disperses the crowd, assuring everyone not to panic. Unfortunately for him, once everyone clears off, Shallert is attacked and implanted by one of the Control Critters. And near the base, General Pattick (Bender), the head military attache of the Space Probe Command Center, also gets attacked and implanted. Their mission accomplished, these alien drones perish upon delivery. These new mindless slaves then dispose of their carcasses.

And so, enthralled by the Venusian, Pattick blames a Communist uprising for all the power outages and quickly declares martial law. But once the base is locked down, Pattick sends the entire garrison out on a reconnaissance patrol to get them out of the way -- about a ten soldiers all told, including Sgt. Neil and Pvt. Ortiz (Miller, Haze).

Here, the Sarge marches his men out of the compound and heads for his assigned observation post several miles away, sets up camp, and awaits further orders. The whole way, Ortiz keeps spotting some "strange looking birds" flying overhead, misidentifying more of those Control Critters.

Meanwhile, in town, when the zombified Shallert orders everyone to evacuate on foot at gunpoint, all-out panic ensues as everyone leaves except for the local newspaper publisher, who refuses to go. For this offense, the sheriff shoots the man dead!

Witnessing this execution, Wilson confronts Shallert but is quickly subdued. However, the sheriff doesn’t actually hurt him and quickly lets the man go, ominously intoning how the retreating Wilson is ‘to become one of them!’

From there, Wilson makes a beeline to the Anderson residence, where, strangely enough, he observes, the power is still on. But confronting Anderson with the cold hard facts about what he's just witnessed, and what kind of fascist society the invading alien demagogue is obviously implementing, does Wilson no good. His friend stubbornly refuses to be swayed and urges Wilson to just give in to the inevitable.

When he refuses, promising to put up a fight, Wilson leaves to do just that. After he's gone, Anderson contacts the Venusian and sadly reports that he was wrong, and his old friend will have to be implanted like the others to bring him in line.

Thus, when Wilson gets home, to his horror, he finds Joan has already been taken over and zombified. Releasing the Control-Critter meant for him, she then locks them in a room together.

But Wilson manages to kill the thing before it can zap him; and then, when his wife returns, Wilson, rather bluntly, shoots Joan right where she stands after confirming there will be no returning back to normal.

Now, I can't begin to describe how brutal this scene is. Wilson doesn't even make a token attempt to help her, or reach her, or encourage her to resist. He just takes her word for it and quickly rationalizes how he must be saving her from an emotionless future, and then matter-of-factly plugs her. Damn, but if that ain't some cold shit right there.

A crushed Wilson shakes this off quickly for he has more work to do to thwart the alien threat. First, he heads back to the Andersons with every intention of biblically avenging his wife.

Since Wilson is proving to be too dangerous, the constantly monitoring Venusian radios a warning to Anderson that Wilson is on the way and commands him to eliminate this threat.

Overhearing all of this, the premeditated murder of Wilson by her accomplice husband proves to be the last straw for Claire. And when he still refuses to listen to reason, she clandestinely swipes Tom’s rifle, calls the Venusian and warns it of what is coming, and then heads for the caves where the alien has been hiding out to kill it and stop this madness.

Back at the house, when Wilson arrives, the two men have it out -- not physically, but verbally. And just when it appears that Wilson might finally be getting through to Anderson, the communicator kicks on.

Apparently, Claire has arrived at the caves and has flushed the Venusian out -- and here, we finally get a good look at the giant inverted turnip that’s trying to take over the world and breathe a huge sigh of relief (-- because there is no way in hell THAT is conquering the world.) *whew*

Meanwhile, Claire scolds the alien monstrosity, calling it ugly, and demands her enthralled husband's release. Then, she fires at the thing repeatedly, but the bullets have no effect as the monster closes in, wraps its lethal claws around her neck, and strangles her to death.

Hearing all of this over the communicator, Anderson finally snaps back to reality. Now vowing to avenge both their wives, the two men quickly devise a plan to bring about the Venusian's demise. They will split up, with Anderson heading to the caves to confront ‘his friend,’ while Wilson will go to the Command Center for some reinforcements and wipe out the others under Venusian control. But those reinforcements might find them first.

See, while scrounging for some food, Ortiz apparently heard Claire’s death-screams and traced it to those caves. And upon further investigation, he not only finds her body but also the alien monster! Then, as it moves to attack him, the soldier hightails it out of the cave all the way to the bivouac, where a flustered Ortiz finally manages to convince Sgt. Neil that the monster he saw was real.

A few barked out orders later, the squad is mobilized and moves toward the caves, guns at the ready. For if it turns out there was no monster, odds are good the Sarge will just shoot Ortiz instead.

Elsewhere, at the Command Center, the two male members of the command crew have been impregnated by the Control Critters, who then kill the uninfected female member of the team, who is down to her nightie for … reasons. The two men then set to work. Seems there are few more Venusians left on the Mother Planet, so another probe is to be sent to bring them all to Earth.

When Wilson arrives on scene, he deduces they’ve all been converted and kills them. (Wow. Again, a little fast on the trigger, there, weren't ya Petey?) Finding the rest of the base deserted, Wilson heads for the caves.

Along the way, he runs into Pattick, who wasn't quite as dead as he thought; and so, he plugs him again and swipes his working jeep. (Geez. I think this guy’s body count is higher than the Venusian's by now.)

Not to be outdone, Anderson runs into Shallert, who gets gruesomely dispatched with a blow-torch to the face.

Back at the cave, once the enemy is confirmed, the soldier's initial attack ends in failure when the creature still proves bullet resistant.

They then suffer their first casualty when Ortiz is killed while trying to run a bayonet through the thing.

Thus, it's only when the Venusian forces the troopers to retreat back outside, and the bazooka team goes to work, do they finally manage to at least slow the monster down.

As this firefight continues, Anderson arrives and confers with Sgt. Neil, telling him to cease firing because he intends to confront the creature face to face -- well, face to kneecap, but, whatever. Sgt. Neil thinks he’s crazy but orders his men to stand down.

With that, Anderson approaches the Venusian, chastises this monstrosity for lying to him all along, and then sticks that blowtorch into the creature’s eye -- it’s only vulnerable spot, apparently, as the monster keels over.

But before the monster dies, it manages to take Anderson with him as it strangles the man to death before it expires.

Arriving too late to shoot anybody else, Wilson views the carnage. He then goes into a big speech about the Venusian’s critical mistake and what makes mankind so great; a monologue that rivals Tom Joad’s explaining how “I’ll be there” at the end of The Grapes of Wrath (1940):

"He learned almost too late that man is a feeling creature, and because of it, the greatest in the universe. He learned too late for himself that men have to find their own way, to make their own mistakes. There can't be any gift of perfection from outside ourselves. When men seek such perfection they find only death, fire, loss, disillusionment and the end of everything that's gone forward. Men have always sought an end to our misery but it can't be given, it has to be achieved. There is hope, but it has to come from inside, from Man himself."

We get a quick recap of all the carnage, then the maudlin score triumphantly swells and escorts us to...

Whenever talking about making It Conquered the World, Roger Corman almost invariably zeroes in on the scene where Claire goes to the caves to confront the Venusian menace.

"Before shooting, Beverly Garland ad-libbed a few sharp lines of her own. From my engineering and physics background, I’d reasoned that a being from a planet with a powerful field of gravity would sit very low to the ground. So with my effects man, Paul Blaisdell, I’d designed a rather squat creature,” said Corman (1990).

“But just before we were about to shoot the climactic showdown with Beverly and the monster, she stood over it and stared it down, hands on her hips. 'So,' she said with a derisive snarl, making sure I heard her, 'you’ve come to conquer our world, have you? Well, take that!' And she kicked the monster in the head. I got the point immediately. Lesson one: Always make the monster bigger than your leading lady."

It’s an enduring Corman legend, told and retold and embellished over time. In another Corman account (Franco, 1978), “When the creature was brought onto the set, Beverly, the leading lady (who excelled in spirited-female protagonist roles), walked over to it, looked down at it, said, ‘So you’ve come to conquer the world? Take that!’ and kicked it. I immediately subordinated scientific theory for dramatic logic, and reworked the schedule to allow for a drastic revamping of the design. I realized that what was right from the standpoint of physics was absolutely wrong for the picture. I reworked the schedule so we wouldn’t shoot the creature until the second day and sent it back to the shop. What was formerly the creature became the new creature’s head, and a new framework was erected beneath that, so that the creature finally towered over the human cast.”

And when we start getting into second and third hand accounts, the oft-told tale gets embellished even further. “Paul’s design was based on two things,” reported McGee (1984). “Roger Corman told him that anything from Venus would be squat and low to the ground because the planet had heavy gravity; [and two] Paul heard Venus was more conducive to plant life than it was animal life. He built a preposterous mushroom with deep set eyes and a wide grin. Beverly Garland sauntered up to it on the first day and said, ‘That conquered the world?’ She kicked it. It fell over. She burst out laughing.”

So now not only had she sneered and kicked the prop, but kicked it hard enough to knock it over. But when you dig into the details, and piece together all of the accounts, odds are good this was all bullshit. I’m not saying something didn’t happen. No. Something like this did happen, just not quite as dramatically flared as it's been told.

“The claim that ‘by that afternoon our monster was rebuilt ten feet high’ is not only implausible, it’s untrue,” said Palmer (1997). “Blaisdell’s Venusian stood six feet high from day one. It was never rebuilt. It was never modified. The fact of the matter is that Corman would never have stood for the amount of time and money it would have taken to rebuild the costume at that late date.”

Here I will disagree with Palmer on one point. In hindsight, the layman, having heard these production stories, repeated by several sources, could think it was plausible that the monster was altered after the fact.

Artist interpretation. (Medium: Billiken Model).

If you look at the Venusian in action on film or look at photos, it seems possible enough that the conical part above the facial features was added on later in an attempt to make it seem bigger. Before that addition, you would’ve had the short, squat, gravity-challenged version Corman and Blaisdell had envisioned. So it was plausible to assume that. It just wasn’t true.

As for kicking the monster over, Bob Burns, Blaisdell’s friend and frequent collaborator, who was on location for much of the filming on the climactic battle, said that would’ve been physically impossible. “The very construction of the costume wouldn’t allow for someone kicking it over,” said Burns (Palmer, 1997). “In fact, it took three off-camera people to tip the thing over when [the Venusian] died at the film’s conclusion.’

However, there is a nugget of truth from which this all sprang. According to her own account (Weaver, 1999), Garland recalled, “I remember the first time I saw the monster. I went out to the caves where we’d be shooting and got my first look at the thing. I said to Roger, ‘THAT is the monster!? That little thing there is not the monster, is it? He smiled back at me, ‘Yeah. Looks pretty good doesn’t it?’ I said, ‘Roger! I could bop that monster with my handbag!’ This thing was no monster, it was a table ornament! I said, ‘Well, don’t ever show us together, because if you do, everybody’ll know that I could step on this little creature!’”

Thus, from that little nugget a legend sprang. And as the old axiom goes, when the bullshit is more impressive than the truth, go with the bullshit.

When Blaisdell began constructing this “miscalculated mushroom,” whom he would affectionately dub “Big Beulah” as it came into being, “Expectations were running high,” said Palmer (1997). “Everyone from AIP prez Jim Nicholson to director Roger Corman felt that this would turn out to be one of Paul’s most awe-inspiring creations.”

In his book, which I highly recommend, Palmer would give a detailed account on Beulah’s construction. Essentially, it began with a wooden lattice framework, like a “plane fuselage or a teepee.” This was then mounted on a base with rolling casters attached to the bottom, allowing the monster to move and swivel back and forth. Blaisdell then began covering this framework with 2-inch thick strips of foam rubber. Its “perambulating protrusions” that formed the bottom fringe were sculpted and cast with latex. Holes were then cut for the arms and forehead antenna to be inserted. And another block was cut out for the creature’s face.

At some point during this process, Blaisdell realized his latest creation would no longer fit through the door of his home workshop. The interior structure stood nearly six feet tall, with a circumference of 12 feet at the base. Luckily, he discovered this early enough that it could still be disassembled without much hassle and then reassembled in a hastily rented space with a larger door.

The antennae were made of latex molded from sculpted wax candles. As for its “scowling visage," the “stalactite teeth” were carved out of white pine and its protruding tongue was also made out of latex. The mouth they were mounted in could be articulated with a set of wires. The eyes were made of plastic with irises painted on before they were implanted into the built-up eye sockets.

Blaisdell then drilled out the back of these orbs and attached a pocket flashlight to each to give them an eerie glow inside the cave. And so, from inside the suit, he could use the flashlight handles to animate the illuminated eyes; grab the ends of the antennae and make them wiggle; and with a few tugs on the wires, the monster’s mouth could open and close while the tongue waved and wagged around.

Which brings us to the arms. Beulah would have a total wingspan of about 12 feet when “her” arms were fully extended to the side. They were built like the body, wooden framework covered in foam and latex, and Blaisdell would sculpt its crab-like pincers. Here, Blaisdell outfitted each arm and pincer with a flexible cable, “which operated like a bicycle’s hand brake,” said Palmer.

“By squeezing an attached grip control, the cable line tugged a pin embedded in one of the pincers, pulling it toward the other. When combined with varied arm movements which Blaisdell controlled from within, the effect was uncannily lifelike. The arms, though cumbersome, were capable of 180-degree arcs of movement.”

When the costume was fully assembled, Blaisdell painted the creature with a bright red paint and then highlighted the details in black. Said Palmer, “On film the bright red color would register as a kind of medium-gray, allowing the highlights to stand out.”

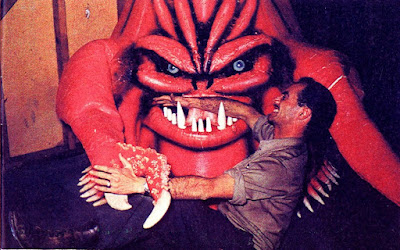

Big Beulah.

Unsatisfied with the glossy finish, Blaisdell and his wife / co-conspirator, Jackie, took up some ball peen hammers and proceeded to beat the crap out of his creation in an effort “to pound texture into the monster’s foam rubber skin” and give it a more organic feel.

Thus, with his monster beaten into submission and now complete, it was time to see if Big Beulah would pass inspection. Said Palmer, “Paul invited Jim Nicholson in to take a look at the life-size version of the model he had presented weeks earlier. Blaisdell crawled inside the costume and began working the controls that operated the claws. To Nicholson’s surprise, one of Beulah’s arms snaked upward, opened a crablike pincer, and swiped the handkerchief right out of his breast pocket.”

(L to R) Paul Blaisdell, a Venusian Mushroom, Bob Burns.

Blaisdell had been practicing that stunt for days with Jackie. The interior of the monster could only be accessed from the bottom. And a singular viewport was drilled right between those plastic eyes. There was barely room for one person and Blaisdell usually operated it alone; but on some occasions Jackie would join him inside if the shot required multiple appendage movements.

Obviously, Nicholson flipped over his efforts. And when it came time for filming, Beulah was loaded onto a flatbed truck and hauled off to Bronson Canyon and then nestled in one of its familiar caves, ready for her closeup. Alas, it wasn’t long before disaster struck.

To his eternal regret, Blaisdell failed to secure the Venusian’s arms above its head and out of the way. Instead, they were splayed on the ground. And as the crew scrambled to get the scene set up and lit, one of the grips rolled a cart loaded down with equipment over both arms, crushing their interior support structure and snapped the control cables, rendering those claws inert, and nearly tearing them both out of their sockets.

Try as he might, Blaisdell couldn’t fix the cables so he would just have to make due with his damaged equipment. When it came time to shoot his confrontation with Claire and her death scene, “There was enough light in the cave during the fading afternoon for Beverly Garland to try and kill me with a Winchester rifle,” recalled Blaisdell (Palmer, 1997). “Beverly has a wonderful sense of barracks language when she gets mad. She’s my kind of gal. There was a lot of cussing on both our parts when the rifle jammed on the first shot and I only got one bullet through my head. I ended up grabbing everything in the cave except her neck.”

With the arms trampled into disrepair, Corman assigned two prop-men to help Blaisdell aim for Garland’s neck. On the first attempt, they completely miscalculated and wound up groping Garland’s chest instead. On the second attempt, they still didn't quite hit the target as Garland ditched the rifle and slid to the ground with the claws almost wrapped around her neck. Close enough. Cut. Wrap. Print.

Disaster nearly struck again when it came time for Ortiz to run the Venusian through with his bayonet. As Corman blocked out this skewering scene with Jonathan Haze, apparently, Jackie Blaisdell sensed “there was too much adrenaline in the air" and started to get a “funny feeling.” She then insisted that her husband borrow and wear one of the army helmets from an extra before shooting the scene. He complied, and sure enough, when the cameras rolled and Haze drove the bayonet through the monster, it struck Blaisdell’s helmet but was safely deflected to the side.

When the scene ended, Blaisdell crawled out of the contraption, thanked his wife for saving his life, and then told Haze to “aim higher next time.” To my eye, the bayonets used were props and made of rubber, but still, who knows what kind of damage that would have caused? But then again, since it had to penetrate the foam rubber, they might've subbed in a real one. Either way, luckily, no one got hurt.

Now, what happened next, again, depends on who is telling the story. According to the script, the monster was never supposed to leave the cave. But! Either someone forgot to bring the generator to run the lights, it ran out of gas, or, more than likely, it broke down. And with no time or money to fix or replace it, Corman made the executive decision, over Blaisdell’s protests, to move the climactic battle outside the cave and bring Big Beulah out of the shadows and into the bright sunlight.

"One weekend a month, my ass!"

On the uneven surface of the canyon floor, those casters were useless, forcing Blaisdell to duck-walk the monster into position for the big battle sequence, where it runs right into a bazooka team.

Said Palmer, “For the scene in which the monster is riddled with bullets, Beulah was outfitted with explosive squibs to simulate gunshots. For reasons of safety Blaisdell remained outside the costume, watching from the sidelines as the soldiers let loose with a barrage of rifle fire. On cue, the squibs were detonated, leaving trails of smoke drifting in the air. When he thought he had enough footage, Corman yelled ‘Cut!’ Here, he failed to notice that Beulah’s interior had become saturated with smoke, which started leaking out of every orifice of the creature’s conical body.”

Dick Miller noticed it first and told his director, “Don’t cut!” But Corman, who was one not to be undermined on his set, screamed, “I said cut!” Meanwhile, everyone else kept yelling “Keep rolling!’ and pointed toward the smoking monster standing behind their director. When Corman finally turned around and saw what was happening, he asked his cameraman, Fred West, “Did you get that?” West said, “No, you said to cut.” Well, “Shit.” said Corman.

When it came time to shoot the climactic showdown between the Venusian and Anderson, as Lee Van Cleef approached the monster, blowtorch at the ready, the crew and the extras gave him a hard time. “Give it to him, Lee!,” one said. Another, “You tell that big ice cream cone where to get off.” Here, according to McGee, Van Cleef allegedly lost his temper and yelled for them to get off his back; it was hard enough to keep a straight face without those other guys horsing around as is.

And to add insult to injury, Corman also insisted the Venusian had to fall over when it died. Once again, Blaisdell protested due to the creature’s bottom-heavy design. But his director was adamant. “I don’t care, the monster has to fall over,” decreed Corman (Palmer, 1997). “How else is the audience going to know that it’s dead?”

I don’t think Corman was wrong on this one. And so, with some help, Beulah was heaved over onto its side, with Van Cleef’s neck clutched in one of its claws as they expired together in one last embrace. Before the camera’s rolled, to assure audiences that it was dead, Blaisdell quickly whipped up two latex eyelids so they would be closed for that last shot. Wait, you say, two eyelids? But wasn’t one of them torched out of its socket?

You would be correct. Only that closeup wasn’t shot on location. No. The moment where the blowtorch is inserted into the creature’s eye and blood gushes out was an insert that was shot later.

According to McGee (1983), “The insert shot of the empty eye socket squirting blood was accomplished by Paul squeezing a grease gun full of Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup. They had some trouble. By the time they were ready to shoot, the syrup had hardened in the end of the gun. Paul squeezed the trigger repeatedly, while Roger screamed at him to do something, and finally Paul squeezed hard enough to clear the barrel. The gun also backfired. Paul crawled from beneath the monster, wiped the syrup from his eyes and noticed he had sprayed Roger as well.”

Palmer’s account is 'slightly' different, saying the insert was shot back at Blaisdell’s home in Topanga Canyon and Corman wasn’t even there. (Odds are good this second unit material was shot by Lou Place.) In his version, it was Paul holding the blowtorch and Jackie was inside the costume with the chocolate grease gun. It still jammed; but Jackie, after a lot of rigorous pumping, was able to clear the congealed obstruction, covering Paul, most of the small crew, and herself in chocolate syrup.

Did any of this actually happen? Who can say, but their end results were gruesomely effective. So effective the film wound up in trouble with the British Censors, who threatened to give it an adults only X-rating.

Apparently, the British review board was hung up on whether the Venusian was a human or animal. If it was human, this was OK. If it was an animal, it was considered too cruel. (Wait. What?! It's okay that the Sheriff gets immolated but the monster is out of bounds?!) Here, Arkoff was able to convince them the monster was the Venusian equivalent of a human being and the film got its general audience release.

Blaisdell also designed and executed the Control Critters, which he referred to as the “Flying Fingers.” There were four of these manta ray-like creatures in total, built of latex and foam rubber, and all but one was rigged to fly. The ones that flew were strung from and animated by a glorified fishing rod, which allowed Blaisdell to give the illusion that the creature’s wings were flapping as they flew around.

Cheap, but effective, “Blaisdell likened the operation to working a marionette,” said Palmer. “He practiced with the Flying Fingers for several days prior to filming and got so good at working the fish-pole rig he could make the bats loop, dive, arc, and just generally ‘go crazy.’”

But the real trick was to keep the actors from getting tied up in the thin wires. Palmer noted how Blaisdell “often remarked on Peter Grave’s ability to smash just about every prop in sight without getting tangled up in the wires during filming.”

Another prop was rigged to run down a wire whenever it was called on to zero in on a target and implant them on a single trajectory. The implantation was announced with an electronic zap and sizzle on the soundtrack, and the spent carrier would leave a visible implant in the back of its victim's neck. The grounded one was more detailed and used for closeups or handling by the actors. This one also came with a built-in air-bladder that Blaisdell cooked up, one of the first of its kind, making it look like it was actually breathing.

Aside from the monster and its accouterments, as far as the rest of the film goes, I think its lofty script ambitions were sold a little short due to budget constraints. Corman was always big on the cheaper, “tell don’t show” method of filmmaking with these early efforts. And there is an awful lot of talking in this movie. To their credit, Graves and Van Cleef manage to punch some life into this tedium but it's an uphill battle the whole way.

“Career opposites, Tom Anderson and Paul Wilson were like the classic mad scientist and his cautious conservative associate,” observed D. Earl Worth (Sleaze Creatures, 1995). “Well adjusted to the system, Paul was successful by its standards. Tom was a wild dreamer who orgasmed on pure imagination. Paul was a plodding doer who could leave his work at the lab most days; Tom a schizoid speculator, always adopting and discarding new theories to suit his moods. Where science was Paul’s way to legitimate achievement within a government-sponsored group endeavor, it was the psychological refuge of a battered ego for Tom.”

Worth also points out that “the alliance between Tom and the Venusian was a preachment against totalitarianism disguised as positive revolution. When the Venusian first contacted Tom, it appealed to his vanity as well as his social conscience. Prisoner of an environmentally-unstable world, the Venusian had good reason to migrate. Like those other alien Flora The Thing (1951) and the Pod People, it was amoral rather than evil, but for melodramatic purposes it was interpreted as a foreign devil -- draining some minds and deluding Tom (into doing its bidding).”

Corman and his editor, Charles Gross, do their best to liven these dialogue scenes up but there’s only so much you can do with a conversation. As for the rest of the cast, Sally Fraser is pretty much window dressing until her turn as a lobotomized minion in a scene that is downright disturbing. (Now imagine if her character was pregnant?) And I will give the production credit as their finished product doesn’t bear the reeking stench of a deus ex machina cop-out of all those possessed returning to normal after the Venusian dies. But come to think of it, everyone who had been possessed was already dead, so the point is pretty moot. Thus, the only real spark in the film comes from Garland.

Beverly Garland would star in two more pictures for Corman -- Naked Paradise (alias Thunder Over Hawaii, 1957) and Not of This Earth (1957), making five in total. She would also appear in Curt Siodmak’s Curucu, Beast of the Amazon (1956) for Universal and Roy del Ruth’s The Alligator People (1959) at 20th Century Fox. But from the 1960s on, Garland switched to television for the majority of her career, most notably on My Three Sons (1960-1972), becoming the second Mrs. Douglas, and Scarecrow and Mrs. King (1983-1987).

“The memories of working with Roger are pleasant because I got along with him very well,” said Garland (Weaver, 1999). “He was fun to be around and work with. We always did these films on a cheap budget, and people were always mad at Roger because he’d hardly feed us. And no matter what happened to you, you worked regardless. He had such incredible energy, it was tremendous -- he was a dynamo to be around.”

And this boundless energy and enthusiasm was infectious. “We’d work very hard for him,” said Garland. “We would work with scripts that weren’t finished. We never had dressing rooms, we never had a john, we never had anything. And we never stopped! We worked our butts off for this guy.”

The movie stumbles on “the bidding” parts, too. The massive evacuation / riot in Beechwood is sparsely staged, and the Venusian’s attempt to shutdown the world is accomplished almost entirely out of stock footage.

But I will say the final battle between the small garrison of troops and the Venusian was ambitiously staged and well executed under the circumstances, making it quite the rousing spectacle as it plays out; with the monster tossing soldiers around while taking on heavy gunfire and a couple of bazooka rounds off its pointy noggin.

Trying to glue all of this together was another Corman regular, Ronald Stein. The composer made his big screen debut with Apache Woman the year before. Here, Stein hadn’t quite found his groove yet as the soundtrack blindly whips around from bombast to melodramatic syrup to circus fanfare. (If I didn't know any better it sounds like the work of Milton Delugg or Spike Jones.) But! He would get better, though. And Stein would continue to work with Corman and AIP, where he was appointed music director, through the 1950s and ‘60s on pictures ranging from Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) to High School Hellcats (1958), his best in my opinion; and from The Premature Burial (1962) to Psych-Out (1968).

As usual, the campaign for It Conquered the World and The She-Creature was smeared with ballyhoo. “Hypnotized! Reincarnated as a Monster from Hell!” and “Every Man its Prisoner, Every Woman its Slave!” SEE! Beauty become a horrible beast from the unknown! SEE! The Earth crushed by a nightmare monster. SEE! The world gripped by terror … panic … death! "It can and did happen! Based on the facts YOU’VE been reading about!"

The Los Angeles Times (August 29, 1956).

Before the film was released, Griffith asked to have his name removed from the credits. However, this was no tip of the hat to Rusoff, who received sole credit. No. This was an attempt to distance himself and avoid blame on the film’s shortcomings.

“The film is terrible,” said Griffith (Senses of Cinema, 2005). “I called [the monster] Denny Dimwit and somebody else called it an ice-cream cone. I was around when Paul Blaisdell was building it and he thought the camera would make it look bigger. I have some photographs of it in construction, probably the only ones in existence. I asked for my name not to be on that picture, so I was unbilled. Surprisingly, it got good reviews.” Well, if it did, I sure as heck had one helluva time finding them.

Abilene Reporter News (September 30, 1956).

“Science Fiction fans and students of the occult will enjoy a double helping of phantasmagoria now on screen at the Paramount,” said Jean Reeves (The Buffalo News, 1956). “If hypnotism and reincarnation tickle your fancy, The She-Creature is your dish. If, on the other hand, the possibility of life on Mars or Venus intrigues and you would be the first in line to buy a ticket to the moon, It Conquered the World will delight your star-gazing sensibilities. This double conjures up two of the weirdest monsters in the screen’s long history of horror folk -- one a creature from outer space and the other a fiend from the deep.”

“It Conquered the World has a more terrifying monster, and an altogether more terrifying turn of events,” observed the Democrat Chronicle (November 1, 1956). “And if we heard of any youngsters of tender age setting up a clamor to see it, we’d lock them up until the whole thing blows over.”

The Omaha World Herald (October 5, 1956).

And Variety had this to say (September 12, 1956), “This flying saucer pic is a definite cut above normal, and should help pull its weight at the box office, despite modest budget. However, militating against this are a number of gruesome sequences which producer-director Roger Corman has injected, and which may call down the wrath of groups who oversee kiddie pix fare. But it must be admitted that the packed house of moppets at the show [we] caught loved the gore, and continually shrieked avid appreciation.”

On the other hand, “The Lou Rusoff screenplay poses some remarkably adult questions amidst the daring-do. Director Corman does a generally good job of mingling the necessary background setting with fast-paced dialogue, to achieve the strongest impact. Only a few patches of abstract discussion fail to hold audience attention.” And lastly, “Corman would have been wiser to merely suggest the creature, rather than construct the awesome-looking and mechanically clumsy, rubberized horror. It inspired more titters than terror."

This man deserved better.

Having learned his lesson with Marty the Mutant, Blaisdell wouldn’t let them use either Beulah or Cuddles, the She-Creature, on any more publicity tours for the new double bill. Regardless, audiences responded, and AIP’s latest combo was their biggest money-maker yet.

Sadly, the Blaisdells would attend the premiere of It Conquered the World, and when the film reached the climax, the audience laughed and jeered at his creation. This so disheartened Paul that they left the theater before the film even finished. This, was too bad.

His work for The She-Creature and It Conquered the World would sort of mark the apex of Blaisdell’s career as a monster maker. So absurd, and yet so practical. And they were like nothing anyone had ever seen before. Both were quite the feat of engineering given the time, the size of the two-person crew, and budget constraints. And each showed a lot of ingenuity in design and execution. And Big Beulah would remain intact until it was destroyed in a massive flood in 1969.

Again, I agreed with Corman that the Venusian had to come out of the cave. And I don’t think it ruined the movie at all. Nope. In my humble opinion, when that sentient toadstool wobbled out of the cave and into a pitched battle, that was one of the greatest moments in cinematic history. No. You read that right.

And it makes me sad that more people can’t see it in all its glory, except for dodgy YouTube VHS rips, because It Conquered the World is another one of those AIP films that failed to make the digital leap because it is held up in constant litigation by Nicholson’s widow, Susan Hart.