After scoring several pop hits on the Hot 100, Sonny and Cher, a husband and wife singing duo, are suddenly red-hot commodities in several Hollywood circles. Even as I type this, despite the couple’s grand indifference on such trivial things, several studios are literally tripping over themselves in order to strike first while things are still molten, hoping to get the couple onto the big screen to cash-in before things cool off.

Well, turns out Sonny (Bono) is a little less indifferent than Cher (Sarkisian), and he officially signs on when a mega-producer named Mordicus (Sanders), who won’t take no for an answer, makes him an offer they can’t refuse, giving the potential stars carte blanche to write a script for their own movie in any genre they so choose.

But now, with a deadline looming, and shooting scheduled to begin in just a couple of days, the ever-procrastinating Sonny’s imagination soon gets the better of him as he runs several movie scenarios past his partner to see if something, anything, finally sticks...

A high school dropout with dreams of being a songwriter, Sonny Bono worked several odd jobs in Los Angeles while trying to break into the music business, including being a waiter, a construction worker, a truck driver, and a butcher's delivery man. That last one would leave a lasting impression on several music execs whenever he would constantly drop by while making deliveries, to submit new songs, still wearing his bloodstained apron.

Bono finally caught on at Specialty Records, where Sam Cooke recorded one of his compositions, "The Things You Do to Me.” Bono then went to work for Phil Spector in 1962, where he co-wrote “Needles and Pins” with Jack Nitzsche for Jackie DeShannon and The Searchers. And it was around this same time Bono hired himself a new housekeeper he’d met in a coffee shop by the name of Cherilyn “Cher” Sarkisian.

Like Bono, Sarkisian had also dropped out of high school and moved to Los Angeles when she was just 16, where she worked as a dancer in several clubs along the fabled Sunset Strip, using these venues to introduce herself to managers and agents, looking for an “in.”

She found one in November,1962, when she first met Bono, who introduced her to Spector, who in turn used her as a backup vocalist for the Wall of Sound on several pop hits, including the Ronettes' "Be My Baby" and the Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin.” And liking the way she sounded, Spector produced Sarkisian’s first single, “Ringo, I Love You,” recorded under the name of Bonnie Jo Mason, which completely fizzled.

Meanwhile, a romantic relationship soon blossomed between Bono and Sarkisian, culminating in an “unofficial” wedding ceremony in Tijuana, Mexico, in late 1964. All the while, Sonny kept pushing Sarkisian as a solo act but she kept begging for him to perform with her due to some crippling stage fright.

Thus, as the duo began harmonizing together onstage as Caesar and Cleo, Sarkisian would focus on Bono to relax, later claiming she always sang to the people through him. Still, as single after single continued to fizzle, the couple hadn’t quite found their sonic signature yet.

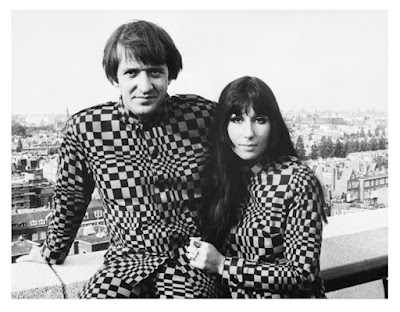

But that all changed in 1965 with the three-punch combo of a name change to Sonny and Cher, the release of the Bono penned single, “I Got You Babe,” and an incident in England when they were both evicted from the London Hilton over the way they were dressed in fur vests and striped bell-bottoms, making them instant counter-culture sensations overnight; and by the end of the year, after the release of Look at Us, their first album as Sonny and Cher, the couple had five songs in the Billboard Top 20.

Musically speaking, with Sonny’s high and nasally voice mixed with Cher’s rich contralto, this shouldn’t have worked at all and yet it did; two highly mismatched puzzle pieces that somehow clicked and locked together. Amazingly so. But all the while, Sonny kept pushing Cher to the front, writing “Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)” and “You Better Sit Down Kids” for her solo album, The Sonny Side of Cher, which also went through the roof.

Then, in 1967, with the release of the follow up Sonny and Cher album, In Case You’re in Love, anchored by the hit single, “The Beat Goes On,” and their popularity at an all-time high, Bono approached his agent, Abe Lastfogel, about the possibility of making a Sonny and Cher movie.

Lastfogel then introduced Bono to a fellow William Morris Agency client, William Friedkin -- a young documentary filmmaker, who was ready to break into features. The two hit it off and started looking for a script.

William Friedkin (Left), Sonny and Cher (Right).

At some point, they got a spec-letter from Nicholas Hyams, which suggested they go meta and make a movie about Sonny and Cher making a movie. They both loved the idea and Friedkin hired the novice screenwriter to flesh out his idea. But! This collaboration didn’t last very long because, according to Friedkin (The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir, 2013), “Hyams was condescending to Sonny and disdainful of me." Thus, the script was eventually hammered out by Friedkin and Bono, and then polished-up by Tony Barrett.

In the meantime, Lastfogel secured financing through Steve Broidy and his newly minted Motion Pictures International. Broidy had been in the movie business since the 1920s, bouncing around between Universal and Warner Bros. He then hired on at Monogram Pictures in 1933, where he steadily moved up the management chain until he was named director of operations in 1945. He then steered the studio out of Poverty Row with a massive upgrade to Allied Artists in 1953, where he remained president until 1965 when he left to form his own company.

Apparently, Broidy had wanted to call the film I Got You Babe to cash in on the hit single, but Bono preferred Good Times (1967), based on a newly penned song he wanted to incorporate into the film. And while the production itself was a bit of a runaway, with the budget ballooning from $500,000 to $800,000 as first-timer Friedkin went a little nuts, Broidy would sell the completed film to an eager Columbia for $1.2-million, making himself a tidy profit. Columbia, however, took a bath, as the film floundered at the box-office and failed to find an audience -- any audience. And the reason for that, I feel, was twofold:

One, the film just isn’t particularly all that good. The whole thing comes off as a pastiche of a half-dozen, half-baked scenarios haphazardly thrown together that both look and read like rejected coconut-cranial-trauma-induced-dream sequences from the old Gilligan’s Island TV-show.

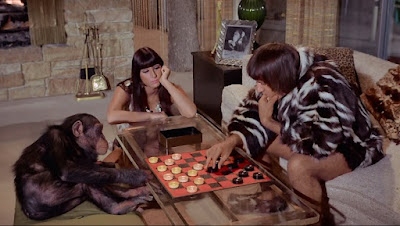

Here, Sonny gets to star and be the hero in a musical western, a hard boiled murder mystery, and a jungle adventure, with Cher playing a different character in each and George Sanders and his goons playing the villains. And then, all the while between “dream sequences,” Bono tries and mostly fails to drum up some enthusiasm in his partner, who really doesn’t want any part in this nonsense. And then Sonny decides he really doesn’t either. And that’s about it.

If one wanted to be generous, you could call Good Times a farce, I guess. Props to Friedkin for giving us a few interesting things to look at, but his burgeoning style constantly clashes with cinematographer Robert Wyckoff’s ingrained TV-sensibilities that keeps the film way, way, way too grounded as it struggles to be hip and kooky.

Apparently, Friedkin shot half the film with a different cinematographer and a three man, non-union crew, guerilla style, and it's very easy to tell one half from the other. Alas, this clashing of styles only adds to the film's problems. Which brings us to the second reason the film flopped.

By the time Good Times came out in May, 1967, the kind of mellow folk music Sonny and Cher were peddling was being pushed off the charts by the likes of Jefferson Airplane and Led Zeppelin. The times, as the song goes, were a changin’. And following Bono’s conservative lead, they refused to adapt with the times.

Now, couple all that with the duo’s well-publicized stance against the notion of “free love” and being staunchly anti-drug, Sonny and Cher were suddenly flaming out and on a fast train to Squaresville. Bono had vainly hoped the film would shore things up, but this, of course, totally backfired.

However, these same conservative stances made the duo very Standards and Practices friendly, explaining why these “safe hippies” spent almost the entirety of the 1970s on TV in some form of variety show, which appealed to a more geriatric audience, starting with The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour (1971-1974), which got a lot of mileage out of Sonny’s self-depreciation and Cher’s bold fashion statements.

But as the couple’s marriage fell apart, so did their act, leading to their own separate series: The Sonny Comedy Revue (1974) and Cher (1975-1976) before they reunited one last time for The Sonny and Cher Show (1976-1977), which always ended with their signature song, “I Got You Babe."

As Bono moved into the 1980s and Cher left him in the dust never to look back, he sort of became his own punchline. And while he still showed up in a few movies and TV-serials from time to time, he apparently started shying away from show-business after a guest stint on Fantasy Island (1977-1984), where he allegedly witnessed Hervé Villechaize have a complete meltdown over some slight affront and washed his hands of the whole business.

But in the end, he just left one media circus for another when he got into politics, getting himself elected mayor of Palm Springs in 1988 -- basically so he could change a city code, which would allow him to put up a bigger sign up on his restaurant.

He was then elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Republican on his second try in 1994, and served in that capacity until his untimely death in 1998 due to a skiing accident. Cher would deliver his eulogy, and his headstone reads: “And the Beat Goes On."

Thus, Bono left behind a very strange and unique legacy. And that might be the best way to sum up Good Times, too. Strange, and unique. Also, pretty forgettable, which is too bad. Luckily, Bob Rafelson would do it all better a year later with The Monkees and HEAD (1968).

Me? Well, I’ve always liked the duo, dug their music, and their shtick. Their variety hour was appointment television on the old Zenith in my family's household back in the day. In his memoir, Friedkin stated, "I've made better films than Good Times but I've never had so much fun." For me, I just wish a little more of that fun had made it into the actual film.

Originally posted on June 10, 2019, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

Good Times (1967) Motion Pictures International :: American Broadcasting Company (ABC) :: Columbia Pictures / EP: Steve Broidy / P: Lindsley Parsons / D: William Friedkin / W: Tony Barrett, Nicholas Hyams / C: Robert Wyckoff / E: Melvin Shapiro / M: Sonny Bono / S: Sonny Bono, Cher, George Sanders, Norman Alden, Larry Duran, Hank Worden

%201967.jpg)

%201967%2008.jpg)

%201967_01.jpg)

%201967.jpg)