These numerous occupants included Glennie Lankford, a widow, who had rented the house, and her youngest children, Lonnie, Charlton and Mary; also staying there were Lankford’s two older sons from a previous marriage, John and Cecil “Lucky” Sutton, along with their respective wives, Vera and Alene Sutton; also in the house were Alene's brother, O.P. Baker, and a couple of friends from Pennsylvania, Billy Ray Taylor, and his wife, June.

It was Taylor who first noticed something “unusual” in the sultry summer air when he went out to pump some water around sundown and witnessed an object moving across the sky. Taylor would later describe its shape as an over-turned No. 2 wash-tub, shooting flames out the back-end, representing all the colors of the rainbow, until it suddenly stopped and then dropped with a hiss into a gully 300-or-so yards behind the house.

“It was like a red wash-tub gliding out of the sky,” Taylor would later recall to reporter Bill Burleigh (The Evansville Press, August 22, 1955). But his outlandish sighting was treated with much skepticism from the others inside the house -- at least it was until the dog started barking up a storm about an hour later.

And so, a little after 8pm, Taylor and Cecil Sutton headed outside to check on the ruckus and spotted a glowing object near the house. Both men would later swear this light radiated from a small, human-like creature that, at first, they thought looked like a little old man or a monkey. But as it got closer, they saw it was neither.

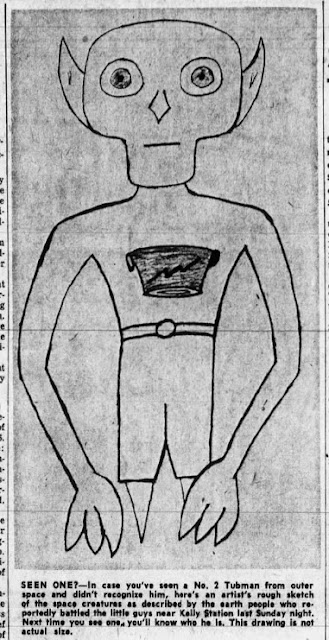

Now, this eerie being was “at least three feet tall, with an unusually large, bald head with crinkly, bat-like ears extending from either side of its head,” reported Burleigh from his gathered eyewitness accounts.

The creature was also “very thin, with disproportionately long arms that ended in talon-like claws.” Reports also claimed the hands were webbed, “and their fingers were about six inches long, and they had ears that came to a keen point.” The creature also had unusually large eyes with no apparent eyelids, no nose, and a lip-less mouth, which extended from one side of its face to the other.

According to further testimony, the creature never touched the ground, only hovered, moving through the air as if it were swimming; and it appeared to be wearing a shiny, silvery metallic bodysuit. “It looked like it was made of aluminum foil,” said Alene Sutton. “It had two big eyes, pretty far apart.” Elmer Sutton later expanded on this description further, saying, “It looked like the bones of a skeleton with shiny metal over them. And their eyes were about six to eight inches apart that shined like new money.”

The Evansville Press (August 22, 1955).

And Glennie Lankford would later describe them to Isabel Davis, a noted Ufologist, who would write the most definitive book about the alleged incident, Close Encounter at Kelly and Others of 1955 (1978). “It looked like a five-gallon gasoline can with a head on top and small legs. It was a shimmering bright metal like on my refrigerator.”

At first the lone creature kept its distance until realizing it had been spotted; and then, arms raised, moved directly toward the house, causing the two observers to beat a quick retreat back inside to arm themselves with a 20-gauge shotgun and a .22 rifle. And when the glowing being was less than 30-feet from the porch the men opened fire. And while they claimed to have hit the creature, the bullets and slugs had no seeming effect except to cause this alien thing to flip a u-ee and disappear from whence it came.

“I shot one twice,” Elmer Sutton later recalled to Burleigh. “I was about 30-feet from the creature when I shot it with the shotgun and it flipped over onto the grass and then fell to the ground. But the creature immediately jumped back up and took off.”

Despite the hasty retreat, this encounter with the strange creature was about to get a lot more harrowing. For there would turn out to be more than one of them. “At first there seemed to be only one,” said Elmer Sutton. “Later, they seemed to be swarming all over the place.”

But as these creatures came back en masse, peeping into windows and terrorizing the whole household, at that point, still thinking there was only one creature, both Taylor and Sutton went back outside to try and run it off again; but the second Taylor set foot out the back door something on the roof reached down and snatched him by the hair.

And while the rest of the family wrested him free, Elmer Sutton blew the offending creature off the roof with his shotgun; but the creature was unharmed and gently lit onto the ground. Said Alene Sutton, “The figure seemed to fly or jump right over the house, land in the backyard, and then vanished.”

Kentucky New Era (August 22, 1955).

Now, it was at this point the besieged family noticed multiple glowing objects in the nearby shelter-belt of trees. They were surrounded. Once again, the men opened fire as they retreated into the house as more and more creatures kept approaching them. But each one they hit would only glow brighter before retreating into the shadows.

Both men claimed “to have exhausted an inordinate amount of ammunition to no avail,” according to Burleigh’s report, who quoted that “when the bullets hit the creatures, they bounced off like from a concrete pavement.” These same witnesses would later describe a metallic sound with each landed shot, like “a coin tossed into a bucket.” And this pattern of attack and retreat lasted for several hours until things seemed to stop around 11pm.

Evansville Press (August 23, 1955).

Thus and so, the house was quickly abandoned as all the occupants piled into two cars and raced into Hopkinsville, where they reported the incident to the Chief of Police, Russell Greenwell. And while the report of a dozen malevolent creatures sounded fantastic, Greenwell sensed the witnesses were genuinely terrified by what they claimed to have seen. And so, he led a patrol in force out to the farmhouse.

Here, Greenwell was joined by Christian County Sheriff’s Deputy George Bates and a quartet of MPs from nearby Fort Campbell; but apart from some broken glass, shredded window screens, spent shells, and a dubious “glowing patch" of something on a nearby fence, no evidence of the creatures was found.

Evansville Press (August 23, 1955).

“More than a dozen state, county, and city officers from Christian and Hopkins counties went to the scene between 11pm and midnight and remained until after 2am without seeing anything either to prove or disprove the story about the ship and its occupants,” reported the Kentucky News Era (August 22, 1955).

This inconclusive investigation wrapped up at approximately 2:30am. But after the cops left and the occupants returned so did the creatures, apparently, as they once again started peeking into windows and crawled all over the roof in defiance of the returned fire whenever they stuck their misshapen heads into view.

This second attack finally petered-out around 5am. And when the sun came up, you guessed it, no solid evidence of these invaders could be found.

Despite the family’s perceived sincerity, Greenwell later admitted to Burleigh that he believed the family might’ve been over-exaggerating due to the lack of evidence. He stated they found “no tracks, no evidence of anyone prowling around” and attributed it all to “hysteria and overactive imaginations.”

The Evansville Press (August 22, 1955).

Deputy Bates agreed, saying, “I think it was imagination that built up from talk that got started among the people. They just got themselves worked up over nothing.” These alleged witnesses, however, disagreed.

“You may be certain in your mind that no spaceship landed with a load of strange outer-world creatures near Kelly Sunday night,” reported Joe Dorris (The Kentucky News Era, August 23, 1955). “But persons at the farmhouse to which the visitors allegedly came are just as certain they did see the little men. The sincerity with which the fantastic but not impossible tale is told was what impressed us most when photographer Harvey Reeder and I visited the scene.”

Pensacola News Journal (August 23, 1955).

“I don’t care if they don’t believe me,” Alene Sutton told Burleigh. “I saw it with my own eyes and if I see any more tonight, I will pack my clothes and leave.” Added John Sutton, who, despite being a Korean War veteran, and claiming to have survived artillery barrages with shells bursting all around him, swore he had never been so scared as he had been that night, saying, “You can believe it or not, just don’t laugh at it.”

On the morning after the alleged attacks, the story was picked up by the AP and the UPI and went national. “State, local, and military police were scouring the countryside today for a “saucer-like” spaceship and its occupants, reported to have landed in a field. The search began last night when Hopkinsville police chief Russell Greenwell received a call from an unidentified person saying a spaceship had landed in the Kelly community. Aided by military police from Fort Campbell, state and local authorities began a check for the spaceship and the 12 little men who supposedly were its occupants. After the preliminary investigation authorities said there was nothing to report but continued the search.” (The Park City Daily News, August 22, 1955).

According to the Madisonville Messenger (August 24, 1955), “Plagued with a solid stream of curiosity seekers, the folks on the farm of Cecil “Lucky” Sutton erected a No Trespassing sign on a tree in their front yard.”

The Nashville Banner (August 24, 1955).

And

when that didn’t work, they started charging folks who wanted to have a

look around: 50-cents just to get on the grounds, $1 for any

information or recollections, and $10 if you wanted to take any

pictures. And the pricing varied, depending on which source you quote from.

This, however, might’ve been a tactical error when it came to the validity of their alien encounter. Because after they started charging money, skeptics blasted them as nothing more than fortune-seeking fabulists.

Kingsport Times (August 24, 1955).

However,

it should be noted that after the initial media blitz, the Sutton

family quickly distanced themselves from the incident and vacated the

property not long after.

Meanwhile, in that same news article, “the Air Force denied [that] any official investigation has been made of the reported landing of a flying saucer filled with shiny little men at the Sutton farm near Kelly, in Christian County, eight miles north of Hopkinsville Sunday night.”

The Madisonville Messenger (August 24, 1955).

Now, it should also be noted that both the sheriff’s department and other area residents claimed to have spotted unusual lights in the sky on that very same August night; and while the glowing creatures never returned to Hopkinsville, the story became legendary in Ufology circles due to its duration and by the number of witnesses involved.

When the story first broke, the local press referred to the alleged alien visitors as the “No. 2 Tubmen” -- which included a lot of embellishment on the visitors’ appearance, including some reports saying the aliens were cyclopean in nature and green in color -- adding the term “little green men” to the popular lexicon. Thus, what was to become known as The Hopkinsville-Kelly Incident was also often referred to as The Hopkinsville Goblins.

The Los Angeles Times (August 23, 1955).

Enter Dr. Josef Allen Hynek, an astronomer and physicist, who was hired by the Air Force in 1948 to investigate reports of flying saucers and other strange phenomena for them under Project Sign -- which would eventually morph into Project Grudge, then Blue Book.

Said Hynek, (The Saturday Evening Post, December 17, 1966), “In 1948, when I first heard of these UFO's, I thought they were sheer nonsense, as any scientist would have. Most of the early reports were quite vague: ‘I went into the bathroom for a drink of water and looked out of the window and saw a bright light in the sky. It was moving up and down and sideways. When I looked again, it was gone.’

Dr. Josef Allen Hynek.

“At the time, I was director of the observatory at Ohio State University in Columbus," said Hynek. "One day I had a visit from several men from the technical center at Wright-Patterson Air Force base, which was only 60-miles away in Dayton. With some obvious embarrassment, the men eventually brought up the subject of ‘flying saucers’ and asked me if I would care to serve as a consultant to the Air Force on the matter.

“The job didn't seem as though it would take too much time, so I agreed. When I began reviewing cases, I assumed that there was a natural explanation for all of the sightings -- or at least there would be if we could find enough data about the more puzzling incidents. I generally subscribed to the Air Force view that the sightings were the results of misidentification, hoaxes or hallucinations.”

The Saturday Evening Post (December, 1966)

Thus, at the time of the Hopkinsville Goblins sighting, Hynek was a skeptic and felt the current spate of UFO-mania, triggered by Kenneth Arnold’s flying saucers sighting in 1947, was a case of mass-hysteria that would soon burn itself out. But Hynek would later admit at the time he would be best described as a biased debunker, a spoiler role he enjoyed, which, he also noted, was exactly what the Air Force expected of him.

This explains why Project Bluebook officially wrote the Hopkinsville Incident off as a hoax, and the going theory was the witnesses -- listed as mostly “itinerant carnival workers,” making them untrustworthy by mere biased association -- most likely encountered a knot of “aggressive great horned owls” and the glowing substance nothing more than transferred foxfire -- a “bio-luminescent fungus” that latched onto decaying wood.

Cincinnati Enquirer (August 24, 1955).

However, over time, Hynek’s views began to change as he grew tired of the “dismissive or arrogant attitude” of both the Air Force, the scientific community, and the media towards UFO reports and witnesses. Said Hynek, “A very real paradox was now beginning to develop. As the Air Force's consultant, I was acquiring a reputation in the public eye of being a debunker of UFOs. Yet, privately, I was becoming more and more concerned over the fact that people with good reputations, who had no possible hope of gain from reporting a UFO, continued to describe ‘out-of-this-world’ incidents.”

This dynamic shift in attitude is best exemplified by an article Hynek wrote in the April, 1953, issue of The Journal of Optical Society of America under the banner of “Unusual Aerial Phenomenon,” where he stated the following:

“Ridicule is not part of the scientific method, and people should not be taught that it is. The steady flow of reports, often made in concert by reliable observers, raises questions of scientific obligation and responsibility. Is there ... any residue that is worthy of scientific attention? Or, if there isn't, does not an obligation exist to say so to the public -- not in words of open ridicule but seriously, to keep faith with the trust the public places in science and scientists?”

Hynek was also struggling with the caliber of witnesses that came forward, a lot of them military pilots, who he felt were well-trained and not prone to delusions or hysteria. And with this quantum shift in thinking, Hynek began to think maybe there was something to this UFO stuff after all.

And so, when Project Blue Book officially folded in 1969, Hynek formed the Center for UFO Studies (CUFOS) in 1973, which continued his avocation for scientific analysis of UFO cases both old and new. And it was around this same time that Hynek published his first book, The UFO Experience: A Scientific Inquiry, in which he proposed a scale of classification for UFO sightings.

The first three levels begin with nocturnal lights, then daylight sightings, and then sightings confirmed by radar. This was then followed by a Close Encounter of the First Kind: or “visual sightings of an unidentified flying object seemingly less than 500 feet away that show an appreciable angular extension and considerable detail.”

Art by Walter Molino.

Then, a Close Encounter of the Second Kind: or “a UFO event in which a physical effect is alleged. This can be interference in the functioning of a vehicle or electronic device; animals reacting; a physiological effect such as paralysis or heat and discomfort in the witness; or some physical trace like impressions in the ground, scorched or otherwise affected vegetation, or a chemical trace.”

And at the top of the scale, a Close Encounter of the Third Kind: or “a UFO encounter in which an animated creature is present. These include humanoids, robots, and humans who seem to be occupants or pilots of a UFO."

Meanwhile, that very same year (1973), Steven Spielberg was putting the finishing touches on a deal with Columbia to make a long desired personal pet-project, Watch the Skies, once he wrapped-up (and survived the making of) JAWS (1975) for Universal.

The proposed film drew inspiration from Hynek’s book; in fact, Hynek would be hired on as a creative consultant once the film went into production (-- and would have a cameo as the pipe-smoker on the "Dark Side of the Moon" during the film’s final act). But once the title Watch the Skies couldn’t be cleared due to a copyright claim, the proposed film was rechristened as Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

Now, it was at some point during the production phase of Close Encounters that Hynek related the tale of the Hopkinsville Goblins to Spielberg -- which might’ve inspired the look and feel of the siege on the Guiler farmhouse in Close Encounters, when young Barry is abducted.

To get all of this on film, Spielberg, of course, was soon in the middle of another runaway production that went both over time and budget -- originally slotted at $20 million -- due to FX glitches and delays, which made the suits at the near bankrupt studio very nervous. In fact, several sources claimed the future of Columbia rested solely on the success or failure of Spielberg’s unfinished film.

Luckily for both, Close Encounters of the Third Kind was a blockbuster and saved the studio. And so grateful was Columbia, they were eager to get another contractually obligated film from Spielberg as soon as possible. In fact, they wanted a direct sequel to Close Encounters, but whether they just wanted more of the same, or something to compete with the forthcoming sequel to Star Wars (1977), The Empire Strikes Back (1980), was anyone’s guess.

But like with JAWS, while he wasn’t all that interested in doing a direct sequel, Spielberg did have some regrets over losing creative control on the other franchise he birthed, which was about to unleash JAWS 2 (1978) -- a film that was sorely lacking the Spielberg touch. And for a while, Spielberg managed to wrestle control of that franchise back a bit and was one of the major proponents for the National Lampoon’s take on JAWS 3 People 0, even bringing in Joe Dante to direct.

But that proposed film had a quick but very painful death when no one could decide if it should play as a PG-rated thriller or an R-rated comedy, opening the door for the gawdawful but highly entertaining JAWS 3-D (1983) and the even gawdawfuller JAWS the Revenge (1987), which the wunderkind director had nothing to do with.

Ergo, not wanting Columbia to just make a sequel without him, Spielberg was anxious to retain at least some degree of creative influence over Close Encounters 2. But since he was then currently busy trying to finish 1941 (1979) -- yet another film destined to get away from him both physically and financially, only this one was destined to be his first box-office dud (-- even though I love that flick unconditionally), and was also in the natal pre-production stages of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Spielberg decided he would not direct the sequel but would try his hand at producing for the first time instead.

Spielberg (left), John Belushi (right) on the set of 1941.

Here, not wanting to repeat himself, and with Hynek’s inspiration, he came up with a treatment that would offer a “dark counterpoint to the awe and wonder of Close Encounters,” where instead of the existential possibilities of benign alien contact, the sequel, once again under the working title Watch the Skies, would feature aliens as unruly visitors with a dubious agenda that included abduction, mind-probing, and animal mutilation as they laid siege on an isolated farmhouse.

In his role as producer, the first person Spielberg brought on board was noted production designer and illustrator, Ron Cobb, who had worked on Dark Star (1974), Star Wars, and Alien (1979), to help flesh-out his pitch to Columbia. This pitch concerned a dozen-or-so malicious alien explorers on a fact-finding mission on Earth to discover what the dominant species was, beginning with animals and then working their way up the food-chain to a human family.

Production design sketches by Ron Cobb.

Now, the first bump on the road to production came when none of the surviving victims of the inspiring Hopkinsville Incident would agree to sign-off on the film. And the second was they still couldn't get clearance to use Watch the Skies. And so, Watch the Skies became Night Skies, and the plot would have to be changed or extremely fictionalized to avoid any lawsuits.

To accomplish this, Spielberg first offered the job to Lawrence Kasdan; but he was too busy trying to salvage The Empire Strikes Back for George Lucas at the time. And so, Spielberg turned to novice screenwriter John Sayles, who had recently penned the script for Roger Corman and Joe Dante’s JAWS knock-off, Piranha (1978); a spoof Spielberg liked so much he personally intervened and called off Universal’s rabid IP lawyers, who wanted to block the release of that film like they did later with Enzo Castellari’s Great White (alias L’Ultimo Squalo, alias The Last Shark, 1981), which, to be fair, was essentially JAWS with the serial numbers filed-off and a hope no one would notice.

John Sayles.

Sayles took the job, immediately went to work, and churned out a 99-page draft for Night Skies: a “grisly yet sometimes quirkily funny tale” that was the tonal polar-opposite of Close Encounters.

Still somewhat inspired by the Hopkinsville Goblins, mixed with tenants of a recent spate of unexplained cattle mutilations that had plagued Kansas and Nebraska from 1974-1976, Sayles' shifted locales from Kentucky to Montana, and his treatment was largely told from the perspective of the youngest siblings of the besieged family: a teenaged girl named Tess, a teenaged boy named Watt, and an autistic 10-year old boy named Jaybird.

And I say “somewhat inspired by the incident" because Sayles would later admit he based most of his draft on John Ford’s historical epic, Drums Along the Mohawk (1939), subbing in hostile aliens for the attacking natives. He even named the head alien Skar after the Comanche war chief in Ford’s The Searchers (1956).

As for the story itself, it featured a group of aliens led by Skar, who, according to the script, were “humanoid, about three feet high, with eyes like a grasshopper,” landing near an isolated cattle ranch in Montana, where they start killing and mutilating the larger livestock and exsanguinating the chickens in their scientific efforts.

The Lincoln Journal Star (August 23, 1974).

“A dead cow lies on its side on the grass. The skin on its neck, from the shoulders to the chin, has been skillfully removed, leaving the membrane and nerves beneath intact. A perfect circle of skin about the circumference of a grapefruit has been removed from its forehead. Its genitals have been sliced out … On the third cow, all the flesh from the base of its neck up is gone, only a cleanly picked skeletal neck and skull are left.” (From the Night Skies spec script.)

Now, according to Sayles, Skar killed these animals by touching them with a long bony finger, which gave off an eerie light from the tip (-- sound familiar? Yeah, to me, too. Hang on, we’re getting there); and with the help of his hench-aliens, Hoodoo, Squirt and Klud, who were all armed with some-kind of optical hypno-whammy, they anesthetized their specimens into a stupor before dissecting them.

By this point, with eyes on the budget, the number of aliens had been reduced from a dozen to five. Thus, the fifth alien was referred to as Buddee, who was kinder and gentler and wound up befriending Jaybird and saves him from being vivisected.

“Buddee appears and knocks Skar’s hand away. SNAP! Buddee backs Skar away (from Jaybird) with a vicious snap of his jaws. Skar and Buddee square off and begin to fight, the others following the action, ranged around them. At first, the two rush at each other with threat displays -- puffing, hissing, snapping -- then both extend their claws and begin slashing at each other.” (From the Night Skies spec script.)

But unknown to Skar, Buddee has managed to raise an alarm with a kit-bashed radio, summoning a more benevolent race of plant-like aliens, who race to the rescue and run the other reptilian aliens off in the nick of time.

As a whole, things start slow in Night Skies with an X-Files like mystery and a ton of human melodrama, but then things quickly accelerate as Sayles' script culminates with an extended attack on the farmhouse, followed by Jaybird’s rescue. And for his betrayal, the film ultimately ends with Buddee left marooned on Earth by his fellow aliens, cowering under the shadow of an approaching hawk as the screen fades to black.

“A hawk soars above. We track along with the hawk’s shadow as it crosses the empty prairie. It flies quite a ways. Finally we come to Buddee, who stands looking up at it. He still has a trace of blue (paint) on his face, a few cuts from his fight. He peers up, shading his eyes with his hand. He begins to walk across the range, looking lost. We PULL BACK slowly into an AERIAL SHOT until he is a tiny figure crossing an enormous expanse of empty range, a solitary stranger in a strange land. CREDITS.” (From the Night Skies spec script.)

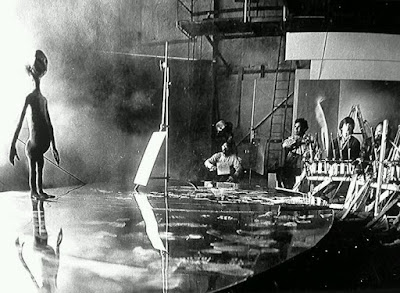

Meanwhile, as detailed in Sayles’ proposed script, Spielberg needed to come up with some aliens that would have to do a helluva lot more than the spindly critter and infantile pot-bellies that showed up during the climax of Close Encounters, which came courtesy of Carlo Rambaldi.

Behind the scenes with the alien "Pot-Bellies."

Said Christopher Meeks in an article for Cinefantastique (Vol. 13, No. 2-3, November, 1982), “The film -- known as Close Encounters II but later titled Night Skies -- would have depended heavily on the success of creating believable extraterrestrials. Spielberg needed something unique, an alien that could be photographed without resorting to heavy backlighting in a smoke filled room.”

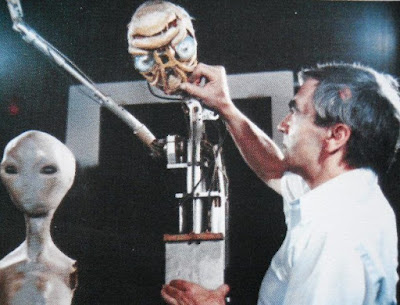

And so, taking advice from his friend and fellow director, John Landis, Spielberg approached Rick Baker, who had salvaged Rambaldi's efforts in King Kong (1976) and was responsible for punching up the cantina sequence in Star Wars with all kinds of alien creatures, and who was currently working out the kinks for his soon-to-be groundbreaking FX for Landis on An American Werewolf in London (1981).

Rick Baker and friends.

“I told Spielberg what he was talking about would be incredibly difficult and expensive,” Baker told Meeks, describing all the as-yet-to-be-invented animatronics needed to pull off what the producer needed. “I named a price off the top of my head, about $3-million.” But Spielberg didn’t even blink at the number. “He said $3-million wasn’t that outrageous, considering there wouldn’t be any other expenses.”

But Spielberg had to get the final OK from the execs at Columbia first before fully committing on Night Skies, who, perhaps still feeling the sting of the box-office disappointment of 1941, were a little hesitant with the green-light. And on top of that, producer Spielberg still hadn’t picked out a director either. But he did have a few ideas on that, too, which he floated by the studio.

Tobe Hooper (left).

Ron Cobb (left).

First up was Tobe Hooper, still notorious for directing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), whose blunt, matter-of-factness had a huge influence on JAWS; but he turned it down as Hooper was gearing up for The Funhouse (1981). Spielberg’s second (and last) choice was promoting production designer Cobb, who had never directed a film before.

Columbia still wasn’t completely sold on this idea or the film quite yet, but they were willing to put up $100,000 for some FX tests. With that, as he was halfway out the door to Tunisia to begin shooting Raiders of the Lost Ark, Spielberg gave Baker the money and the go ahead to begin work developing a prototype of the state-of-the-art automaton to the tune of $70,000. This assignment, Baker said, “Was a dream come true.” And, yeah, we’ll call that ominous foreshadowing over what was to follow, my Fellow Programs.

The Leaf Chronicle (August 24, 1955).

And so, Baker went to work on the alien’s design for Night Skies. “One of the girls in the Kentucky family drew a picture of what the aliens looked like,” said Baker. (Editor's Note: Odds are good Baker was referring to the dictated sketches of Gary F. Hodson, illustrated above.) “I didn’t want to build that, really. It had a triangular head and body, and weird hard angles.” He also pretty much ignored Sayles' descriptions in the script.

“I knew the alien had to be able to communicate its emotions through expressions,” said Baker. “Therefore, it had human-like features: two eyes, sort of a nose, and a mouth. But the body got very strange. It had almost a dog-like rib-cage, a long spiny abdomen and frog-like legs. It was a very textural thing with wrinkles, scales and folds. It stood four feet tall when erect, but I envisioned it walking hunched like an ape.”

Baker's design sketch for Skar.

Once the prototype was completed, Baker sent photos and a videotape of the creature in motion to Spielberg, now hunkered down in Tunisia; and the producer absolutely flipped out with glee at the progress Baker had made. Then, Spielberg’s assistant, Kathleen Kennedy, called Baker with the good news, saying their boss was ecstatic, and how his efforts made "Yoda look like a toy.”

“She went on and on about how great it was,” Baker told Meeks. “I was pretty pleased, myself, though there were still some bugs to be worked out.”

Image courtesy of Rick Baker.

Baker’s efforts would give the film a much needed shot of momentum that it so desperately required at the time. See, Columbia was still in a dither over the film’s budget -- not helped by the fact that Baker couldn’t give them an exact amount needed for the FX because the film not only had no storyboards at that point but the script wasn’t even finished yet! (There was even a rumor floating around Hollywood that Spielberg contacted NASA to reserve cargo space on the inaugural space shuttle flight in order to film the Earth and the Moon for the opening sequence -- and who knows how much THAT would’ve cost.) But thanks to the stellar results of the prototype, the studio agreed to spend another $500,000 on research and development on the aliens.

And to those ends, Baker set up a new workshop and hired on six assistants to work simultaneously on the aliens needed for Night Skies and the wolfman for American Werewolf in London, pushing himself hard, working long nights and weekends to pull off what Spielberg and Landis needed.

Image courtesy of Rick Baker.

Said Baker, “Eventually I got a script giving me descriptions of the characters and what their personalities were. One of the aliens was named Scar (sic), a real badass. A little cute one was called Squirt, and there was Buddy (sic), a nice creature.”

Yeah. Things were looking pretty good for Night Skies at this point, but then came a fateful night out in the deserts of North Africa, when Melissa Mathison showed up to visit her then boyfriend and future ex-husband, Harrison Ford.

Melissa Mathison (left), Henry Thomas (right) on the set of E.T. and Me.

Mathison was a screenwriter, who co-wrote The Black Stallion (1979) for mutual friend, Francis Ford Coppola; and at some point during a lull Spielberg read the entire Night Skies script to her and by the end she was in tears -- no, not because it was bad, but because she fell in love with the notion of “an alien creature who was benevolent, tender, emotional and sweet ... and the idea of the creature's striking up a relationship with a child who came from a broken home was very affecting" to her.

Spielberg, meanwhile, had just come off the mounting chaos of 1941 and had been up to his neck in the serialized adventures of Indiana Jones for several months; and perhaps caught up in a sudden mid-life crisis / anxiety attack, he concluded right then and there that he needed to leave this kind of violence behind and decided to essentially scrap Night Skies altogether. Well, all except for that one plot thread about the xenomorphic friendship, which he would make an entire movie out of instead. He then convinced Mathison to write it. And eight weeks later, she turned in a rough draft for a film called E.T. and Me.

Image courtesy of Rick Baker.

Said Spielberg in hindsight (The Films of Steven Spielberg, 1986), when asked about the darker content of Night Skies, “I don’t know, I might’ve taken leave of my senses. Throughout Raiders I was in between killing Nazis and blowing up flying wings and having Harrison Ford hanging from vines and all this high-serialized adventure. I was sitting there in the middle of Tunisia, scratching my head and saying, I’ve got to get back to the tranquility, or at least the spirituality of Close Encounters. My reaction was to immediately think of a very touching and tender relationship between an extraterrestrial and an 11-year old child who takes him in.”

The exact sequence of what happened next is a bit fuzzy. But what we do know for sure is Sayles, after reading Mathison’s script, was philosophical about the change of direction. Feeling his script was just a sign post or jumping off point, he shrugged, gave his blessing, and amicably walked away with no hard feelings. As he told Antonio D’Ambrosio (The Believer, March 1, 2009):

“I did this script called Night Skies where the last page is about an extraterrestrial being left behind on Earth,” said Sayles. “[This last page] became the first page of the script for E.T. and Me. While I think it didn’t inspire them, I did write the script for Spielberg’s company. They asked if I wanted any credit and I said no, since I felt that I really didn’t have any part of the final script. I also thought that it was a nice script and if they kept the budget down it could be a nice little Disney movie.”

This abrupt change in direction, however, did not go over quite as well with Baker, who remained mum on the subject for almost twenty years until all of this was dug up again by David Hughes for his indispensable book, The Greatest Sci-Fi Movies Never Made (2001), which devotes an entire chapter to Night Skies, where it went wrong, and what it eventually wrought.

Image courtesy of Rick Baker.

Seems after wrapping Raiders, Spielberg walked into Baker’s workshop to give him some good news and some bad news. And here, unaware of Spielberg’s change of plans, he was told the bad news first: Night Skies wasn’t going to happen. And then the good news: they were going to make another, nicer alien movie called E.T. and Me together instead.

Said Baker, “He walks in one day and says something like, ‘Guess what? I’m not making this movie anymore. My jaw dropped. My heart skipped a beat. I almost felt like crying.” But then he said, "I am going to make another picture which is going to have an alien in it -- a cuter alien -- and I want you to start re-designing him.”

Images courtesy of Rick Baker.

Perhaps if Spielberg’s approach had been a tad more nuanced, here, more understanding, Baker might’ve been a little less paranoid and taken the news a little better. As is, he’d spent almost $700,000 developing the aliens for Night Skies, and now, after all that work, sweat, and long hours, all of it was going to be scrapped on, basically, the whims of the producer, who just couldn’t understand why the veteran FX man was so pissed off at the news -- and make no mistake, Spielberg was a little pissed off, too, that Baker wasn’t as excited as he was over this new prospective film.

At the time of the announcement, Baker, being merely days away from filming An American Werewolf in London, was a little stressed at the moment and he really didn’t have the time to start over and tackle such a massive overhaul. And on top of that, what would happen if Spielberg decided to change his mind again, again?

Images courtesy of Rick Baker.

And so, tensions were high, and a fight suddenly broke out over Baker’s understandable lack of enthusiasm for the new film. But according to the Meeks interview, the real stumbling block was money, as Spielberg thought Baker’s revised budget estimates on E.T. and Me were too high, considering that the number of aliens had now been reduced from five to only one.

According to Kathleen Kennedy, she told Meeks, “Steven felt that Rick wasn’t as concerned (as he was) about the money and schedule. When we went to sit down with Rick and decide on a schedule, and see whether, with changes, we could do it at a lower cost, Rick wouldn’t talk to us, and insisted we talk to his attorney.”

Image courtesy of Rick Baker.

Baker, however, had a reason for insisting his attorney get involved, saying, “I was very paranoid with Steven Spielberg because I heard from so many people [who said], ‘Watch out for Steven, he’ll stab you in the back. And Steven is very paranoid of special effects guys. I was treating my situation with Steven differently than I had with any other job, because I heard that you had to protect yourself with this guy.”

And so, tensions were high, and after three weeks of proposals and counter-proposals, negotiations between the two parties irrevocably broke down. Baker, now fully committed to American Werewolf, was going to turn preproduction of E.T. and Me over to his assistant, Doug Beswick; and even offered to take a personal pay cut since he wouldn’t be directly involved on the film until he wrapped with Landis. But he didn’t even get a chance to present this proposal as once again tempers quickly flared and threats of lawsuits flew.

Carlo Rambaldi (Close Encounters of the Third Kind).

Said Baker (Cinefantastique, November, 1982), “I told him that this is a different situation, the old movie was no more, and (therefore) the old contract was no good.” This, according to Baker, caused Spielberg to explode with invective and ended with him walking away, but not before declaring that he was shutting Baker’s workshop down. And just before he left the building, he said -- nice and loud so Baker could hear, “Go call Carlo Rambaldi!”

“I think he thought I was going to ask for more money,” said Baker. “He never listened to what I was offering to do to finish the film.”

The next day, Baker was locked out of his shop and all of his work for Night Skies was seized and confiscated by the studio -- designs, models and animatronics that would essentially form the basis of Rambaldi’s E.T. puppet, including that glowing finger. And to add insult to injury, in an interview with TIME magazine (May, 1982), perhaps painting himself as the hero who saved the production (-- or more than likely this was in retaliation for all the praise Baker had received for his work saving King Kong '76 after Rambaldi's giant robot Kong was essentially stillborn), Rambaldi took a massive shit on Baker’s efforts, referencing an “unnamed effects crew” that “tried to make the spaceman and failed, spending a reported $700,000.” Baker, of course, took this egregious fallacy personally.

“It was very upsetting to me,” said Baker (Cinefantastique, November, 1982). “I was working weekends and long nights to do this stuff. I think I did some of the best work I’ve ever done on that picture. And the thanks I got was saying I wasn’t competent.”

Rambaldi (left), E.T. (right).

Here, according to the Hughes book, it should probably be noted that after their falling out, Rambaldi actually wasn’t Spielberg’s first choice to replace Bakerand realize the alien for E.T. and Me. But Chris Walas turned it down due to him working with David Cronenberg on Scanners (1981). But Walas would go on to have his own horror stories to tell about Spielberg’s last-minute course-corrections during the production of Gremlins (1984). And Rob Bottin, who had just wrapped up The Howling (1981) for Joe Dante, was now committed to do some amazing things with John Carpenter on The Thing (1982). And so, Spielberg was kinda stuck with Rambaldi, who was notoriously slow; but who eventually won himself an Academy Award based on Baker’s designs.

Yeah, one doesn’t have to look all that hard to see that a lot of Baker’s “incompetence” still showed up in Rambaldi’s work. “I hadn’t looked at my Night Skies stuff for a long time, because it kinda hurts,” Baker told Meeks. “But recently, I put the pictures side by side, and there are an amazing number of things taken from my design. Some of the mechanics are exactly in the same place, and I can point to the wrinkles in exactly the same place -- only it’s not as well sculpted as mine.”

And, concluded Baker back in ‘82, “If Spielberg and Rambaldi are claiming that the thing I did was no good, why don’t they give the OK to publish pictures of it? I would like to have the opportunity to prove what I did was not inadequate, but actually quite exceptional.”

At the time of the article’s publication (1982), both Spielberg and the studio refused to release the photos Baker was referring to. And those photos would remain unseen until Baker finally said, screw it, and published them some thirty years later on his Twitter account in 2014. (I’ll assume some statute of limitations had expired because, as far as I know, he didn’t get sued over this.)

And so, you can kinda understand why Baker would never work for Spielberg directly again. And Baker wasn’t the only problem Spielberg faced as Colombia's president, Frank Price, wasn’t real happy with Night Skies’ new direction either, having already blown nearly a million on pre-production with now nothing to show for it (-- during negotiations, Spielberg tried to fold that money into the budget of his proposed new film but this didn’t fly).

And besides that, the studio already had a “benevolent alien visitor” film in the pipeline -- which would eventually see release as Starman (1984), and weren’t real thrilled with Mathison’s script, feeling, like Sayles, it was a “wimpy Walt Disney kids’ movie” that no one would want to see.

And so, Price kinda washed his hands of the whole thing as the former Night Skies - now - E.T. and Me production was tossed into the dreaded abyss of the Hollywood turnaround, writing the whole thing off for tax purposes, meaning the studio and Spielberg could no longer exploit the property any further -- unless another studio stepped in and took over the debt.

“E.T. and Me was a very personal story about the divorce of my parents,” said Spielberg. “How I felt when my parents broke up. When I was a kid, I used to imagine strange creatures lurking outside my bedroom window, and I'd wish that they'd come into my life and magically change it.”

Thus, ever the wheeler-under-the-table-dealer, an invested Spielberg wasn’t ready to give up on E.T. and Me just yet. And so, he first fulfilled his contractual obligation of a sequel for Columbia by cobbling together a few cut scenes and splicing them into Close Encounters for The Special Edition (1981). (And how he actually got away with that crap is mind-boggling to me.)

He then contacted his old friend and mentor, Sid Sheinberg, over at MCA/Universal, who was more than happy and eager to collaborate with Spielberg again on E.T. and Me, negotiating a deal with Columbia where they agreed to not only reimburse the money Baker had spent but also guaranteed the rival studio 5-percent of the new film’s net profits.

History, of course, shows Columbia made a huge mistake by letting E.T. and Me go, as E.T. the Extraterrestrial (1982) would go on to be one of the biggest money-makers of all time, grossing nearly $800-million since its initial release. The running joke around Columbia in 1982 was how the studio actually made more money on E.T. than any of their own in-house releases. And later, while bemoaning the money he walked away from by taking his name off the credits, Sayles said, “Now you can see why I’m not a studio executive.”

As for Frank Cobb, remember him? Well, he also made out pretty good, too, as the appointed director of Night Skies was guaranteed 1-percent of the net profit of the finished film whether he directed it or not. He made millions for, essentially, doing nothing. Hollywood, amIright?!

Still, even with the massive success of E.T. it’s still too bad that Night Skies never saw the light of day. Again, imagine a feature-length version of the raid and abduction sequence at the Guiler house from Close Encounters, produced by Spielberg, back when he still wasn’t afraid to scare people, directed by Tobe Hooper or Ron Cobb, scripted by John Sayles, back when he was writing things like Alligator (1980) and The Howling, with aliens and butchered cows rendered by Rick Baker, who landed himself his own Oscar for his spectacular work on An American Werewolf in London and Men in Black (1998) in the interim. And if you can’t imagine it, well, you can still kind of see it. Sort of.

See, turns out Spielberg wasn’t quite ready to give up on Night Skies just yet either. Turns out “the film that wasn’t” that had already sprung one major blockbuster was destined to inspire another bona fide hit. All you had to do was sub in some ghosts for the aliens and you wind up with Poltergeist (1982), another film with another harrowing Spielberg-tinged production story that we covered at the old Bloggo. You can even see some of it leaching into Gremlins -- especially a comical fight in a kitchen between Squirt and the children’s grandmother.

Night Skies would also share similarities with the omnivorously chaotic Horror / Comedy Critters (1986), which is both hideously underrated and rightfully earned a franchise and a staunch cult following. It also comes closest to what Night Skies could have been. But would Night Skies have found the same success as E.T.? Maybe, but maybe not. For even back in ‘82 Baker thought “Steven made the right choice. I would have loved Night Skies, and so would people who like Science Fiction and Horror. But I doubt if it would appeal to as many people as E.T. did.”

And his opinion rings true -- especially when you compare the box-office results of the heartwarming E.T. (released May 26, 1982, earning $360 million) and the grisly paranoia of The Thing (released July 25, 1982, earning $20 million), which was rejected wholesale by audiences and would be both a critical and financial flop upon its release -- even though I contend the Carpenter film has aged much better than Spielberg’s film, and Bottin’s FX hold up astonishingly well and run circles around Rambaldi’s efforts.

Thus, as the sun inevitably rises and once again chases Night Skies back into the shadows, all we can do is scratch our heads, shrug, sigh, and collectively wonder what might've been.

Originally posted on October 19, 2017, at Micro-Brewed Reviews. And remember...

%201977.jpg)

.jpg)

%201977.jpg)