After trading barbs with a slovenly obese drunk, whose volume and obnoxiousness was ruining the musical act on stage, a man, short in stature and temperament, is given the bum’s rush out of this nightclub for causing trouble (-- he’s literally picked up by a bouncer after an off-screen dust-up and deposited on the street).

Here, the ousted customer, his motor-mouth still running, manages to set the bouncer against the maître d' and his terrible French accent. All of this, of course, establishes how the man, whom everyone calls Shorty (Miller), has a giant chip on his shoulder, is keenly aware of the human condition, and can instinctively read people and size them up in an instant.

He then takes a great pleasure in using these skills to push some buttons, cause some chaos, and cut perceived loud-mouths and bullies off at the knees before punching them in the mouth. And if we didn’t know any better, one would think he was most likely overcompensating for something. But what could it be..?

Anyhoo, before those other two come to blows, Shorty moves on, finding refuge in a seedy little watering hole-in-the-wall called Cloud Nine. The owner, Al (Morse), recognizes Shorty, serves him a drink, before returning to the perpetual conversation he was having with an overly morose reporter named Steve (Cutting), who constantly refuses to drum up any publicity for this self-proclaimed dive.

Now, this ‘dive bar’ in question is currently occupied by those three mentioned; also present are a burly truck driver named Angie (Alcaide), his brassy, ball-bustin’ date, Mabel (Cooper), and an amateur boxer, whose manager, Marty (Hoyt), refers to as ‘The Kid’ (Dickerson).

Marty sees a great future in the ring for his new fighter, maybe even a shot at the title; but he must convince the Kid to turn pro first. His biggest obstacle thus far is the Kid’s wife, Sylvia (Morris), who begs her husband to abandon this career before any permanent damage is done in the ring; which leaves one last other man at the bar, a racketeer (Karlan), there to collect this month’s protection payment from Al.

Then, interrupting all of this patented melodrama, in blusters a bowling-pin shaped beatnik going by the handle of Sir Bop, dig, who tries to foist his latest in a long line of alleged musical sensations onto Al, hoping to earn a spot at this puny platform as the first step to super-stardom.

Alas, Julie (Dalton), overcome by first time jitters, blows the audition rather badly. And while everyone else prods her to try again, Shorty pipes up and delivers a blistering but honest review of her shaky performance. Undaunted, when Al agrees to give her another shot, Sir Bop (Welles) promises to return later with her backup band to give his singer a much needed morale boost for this second try.

But just as things settle down again, another man rushes in (Nelson), who excitedly tells the others about a robbery and shootout he just witnessed, where two mom and pop grocers were killed just up the street -- not realizing the two felons who botched this caper beat him into the bar to avoid the swarming police dragnet. And once he recognizes them, this witness tries to flee the premises only to be shot in the back by Jigger (Johnson), the obvious leader of this highly-strung duo, which is rounded out by his jittery partner, Joey (Haze).

With that, as these two nervously pace and wave their guns in everyone’s faces, they hatch a plan to hole up in the bar, holding everyone hostage, until the heat dies down. And to pull this off, Jigger wants this place to appear normal -- so they’re gonna need some noise. And so, to set the proper atmosphere, he coerces Julie into singing again -- and to sing as if her life depended on it because, at the moment, it most definitely does...

When Charles B. “Chuck” Griffith left Chicago and moved to Hollywood in the 1950s, he had hoped to become a songwriter. He moved in with his grandmother, Myrtle Vail, and managed to latch onto the latest stage production of Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson, Tsk, Tsk, Pare.

At the time, Olsen and Johnson were a famous comedy duo. Almost forgotten today, at the time, they were nearly as big as Abbott and Costello with their brand of pure anarchy and had starred in a series of films, including the totally gonzo Hellzapoppin' (1941) and Ghost Catchers (1944).

Around the same time, Griffith’s gramma Vail was trying to break into television writing teleplays. Vail was a former vaudevillian, who transitioned to writing for radio in the 1930s and ‘40s, where she launched and starred in the transistorized soap opera, Myrt and Marge (1932-1946), for CBS-Radio.

Here, Griffith started helping her write some spec-scripts and sold a couple through her agent -- though none of them were ever produced. And it was some of these same scripts that mutual friend Jonathan Haze, an actor, passed on to Roger Corman, who liked what he read enough to pair Griffith up with Mark Hanna, an actor who was also transitioning into screenwriting, and commissioned them to write a couple of treatments for him

Roger Corman (left), Chuck Griffith (right).

“The first script Mark and I wrote for Roger was Three Bright Banners. The second was Hangtown,” said Griffith, testifying in Corman’s autobiography, How I made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (1990). Three Bright Banners was a dime-store Civil War epic and Hangtown (alias The Girls of Hangtown Mesa) was a Western. “Neither got made, but at least a struggling, unsold writer could get his work to Roger when you couldn’t get it to anyone else in town.”

And they kept on trying until, “Finally, Roger suggested a Western in which a sheriff dies trying to clean up a town and his widow carries out his work,” said Griffith. “That became Gunslinger (1956), the first of many pictures I wrote for Roger.” Corman would also take another run at Hangtown with Lou Rusoff, which eventually saw life as The Oklahoma Woman (1956)

Griffith's second feature came when Corman handed him an outline for a script destined to become It Conquered the World (1956), which concerned an alien invasion from the planet Venus by a sentient chunk of fungus that looked like an inverted turnip -- just another American International ten day wonder.

The original treatment for this had been written by Rusoff, American International Pictures’ stock screenwriter. And, well, “Griffith read the script and concluded that it was incomprehensible,” reported Mark Thomas McGee (Fast and Furious: the Story of American International Pictures, 1984).

“Griffith was given just 48 hours to write something they could shoot,” said McGee. “He wrote streams of dialogue without looking at Rusoff’s script again. He knew Roger didn’t have the money to show anything. (And so, he concluded), the picture would, in essence, be one end of a radio conversation.”

Coming from a radio and TV background, Griffith, who would go uncredited on the film, was used to these kinds of ridiculous time constraints and drop-dead deadlines and managed to salvage the script in less than two days. And along with some strong performances by Peter Graves, Beverly Garland and Lee Van Cleef, and another memorable monster courtesy of Paul Blaisdell, while it failed to conquer the world, the finished film did surprisingly well at the box-office.

These efforts would usher in a long collaborative career with both Corman and American International for Griffith, serving as a screenwriter or script-doctor. Over the next few years Griffith would team up with Hanna again on Flesh and the Spur (1956), Not of this Earth (1957), The Undead (1957), Naked Paradise (alias Thunder Over Hawaii, 1957) -- which would later be recycled wholesale for both Beast from Haunted Cave (1959) and Creature from the Haunted Sea (1961).

“Roger is fascinating to work for,” Griffith told J. Philip di Franco (The Movies of Roger Corman, 1979). “He is both reckless and conservative. He comes up with a ‘what if’ sort of idea and passes his enthusiasm on to others. Then his fears that the money is being wasted -- that the idea being tried is too far out -- creep in. You get an unusual heavily flavored film. And this is a repeated process. Roger has a lifetime of near misses.”

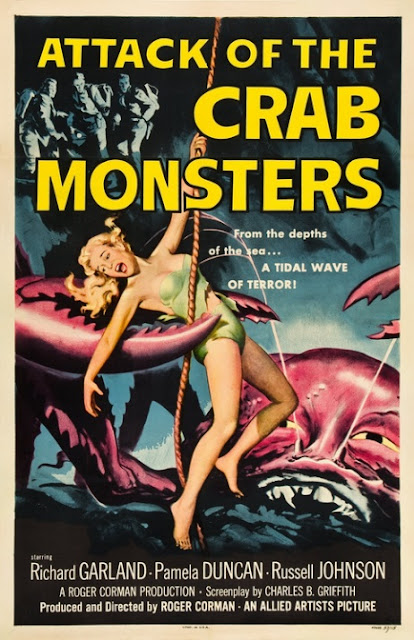

On his own, Griffith wrote Teenage Doll (1957) for Corman and the Woolner Brothers, which was a juvenile delinquent picture that focused on society’s ills through the prism of an all-girl street gang. And he would join Corman at Allied Artists for Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957).

Said Griffith (Franco, 1972), “When Roger first told me he wanted to do this crab picture, he said, ‘I want suspense or action in every single scene. Audiences must feel something could happen at any time.’ So I put suspense and action in every scene … Usually, I did a draft in two, three weeks, with very little discussion with Roger. Then he’d take my first draft and say, ‘Let’s tighten this up a little.’ So I’d make a few changes and type it over with wider margins. That gave me a lower page count and Roger was happy.”

Around this same time, Griffith saw underwater expert Jacques Costeau’s first picture -- most likely The Silent World (1956), which documented life under the sea by those who explore it. Griffith loved what he saw, and was so inspired he wrote a lot of underwater scenes into the script, and then offered to direct all these aquatic scenes for Attack of the Crab Monsters for the princely sum of $100. Of course, at the time, Griffith didn’t know a thing about directing a motion picture -- let alone having no experience as a scuba-diver. Said Griffith (Corman, 1990), “It never occurred to Roger that I didn’t know anything about diving OR directing.”

Then, while Corman was in Hawaii filming Naked Paradise and She Gods of Shark Reef (1958), Griffith got a call from his producer, who informed him the cast of Attack of the Crab Monsters were ready for their scuba diving lessons that he was supposed to supervise, being the underwater director and all, that very day! The jig, as they say, was up.

Luckily, his friend Haze knew how to scuba dive. “I immediately called Jackie Haze, who was bringing the gear.” He told Haze to come fifteen minutes early for a quick crash course before the cast arrived.

Luckier still, no one got the bends. And despite being unable to get the Styrofoam and fiberglass based monsters to sink properly, the underwater shoot went well enough and the film was another hit. This gained experience also allowed Griffith to direct second unit on Not of this Earth.

Which brings us to Rock All Night (1957), the first in a very brief spurt of rock ‘n’ roll exploitation vehicles for American International. “From the beginning, I believed that we had to target our audience and advertise our pictures for the young dating crowd,” said AIP co-founder, Samuel Arkoff in his autobiography, Flying through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants (1992).

“We found our niche and stuck with it, and knew who our ticket-buyers were going to be before the cameras even rolled. When Roger Corman first began working with us, he didn’t immediately recognize the potential of the teen market that became critical to AIP’s success. His early movies with us, such as The Fast and the Furious (1955) and Apache Woman (1955), were not youth pictures. But before long we convinced him that this was a viable audience we were tapping (into).”

And while on the (poster) surface this would appear to be just another entry equal to the likes of Shake, Rattle, and Rock (1956), Don’t Knock the Rock (1957), or even Hot Rod Gang (1958), after the spiffy opening coda featuring The Platters, Rock All Night actually owes more to the likes of The Petrified Forest (1936) or The Desperate Hours (1955), which featured other cinematic groups of innocent (and not so innocent) bystanders becoming hostages and pawns of desperate criminals, and the resulting mind games of cat and mouse -- only the mouse is already caught, letting the cat sadistically play with its prey, where winning equals surviving and losing means, well, not that.

However, Corman’s film was, indeed, initially intended to be another one of those spotlight showcase features; this time focusing on The Platters. What happened? Well, after consulting several different and conflicting recollections from Arkoff, Corman and Griffith, I think we can piece together a fairly reasonable facsimile of what most probably went awry resulting in the film we actually got instead of the one we didn’t:

Seems songwriter and talent manager Buck Ram got wind that AIP was looking to cash-in on the rock ’n ’roll fad, struck a deal, and offered up several acts in his stable at a discount rate, including The Platters, the Eddie Beal Sextet, and The Blockbusters, in return for the sole rights to a soundtrack album for the impending feature. The AIP brass then looked to Corman to provide said feature to attach this LP to from the ground up.

Said Corman (1990), “Just around the time of the release of (Bill Haley’s) “Rock around the Clock,” AIP wanted to jump on the trend. In fact, they wanted to jump so fast they gave me no time to develop a script.”

Thus, Rock All Night would be another one of those quick turnarounds for Griffith, who was charged with taking these musical elements and cramming them into an already existing TV script Corman had optioned, thinking it would make a great feature.

“I had recently been impressed by a half-hour TV drama set in a bar called The Little Guy,” explained Corman (1990). “I thought we could change the bar to a rock and roll club and add some music.”

Thus, the majority of the film was actually based directly on an Emmy Award winning episode of the anthology series, Jane Wyman Presents (S1.E5), where Dane Clark played Shorty and Lee Marvin had the role of Jigger, which aired back in 1955. The original teleplay was by David Harmon, which was written to fill up 24-minutes of airtime. Thus and so, Griffith reworked the script and added several characters and other elements to expand the storyline, moving the action from a saloon to a rundown nightclub, where the featured acts would perform throughout this night of terror.

But complications soon arose when a last second scheduling error found their main attraction (The Platters) out on tour a week earlier than everyone thought, and therefore, unavailable during the allotted six day shooting schedule.

Said Corman (1990), “AIP had signed the Platters to sing as well as appear throughout the story. But because of a scheduling error, they were on tour and couldn’t come to Hollywood. So we had to furiously rewrite without them, shoot the rest of the film, and wait until the group was available for one section of the story. I finally got them for a day in the studio and they lip-synced two of their songs.”

But that was later, as for now, a panicked Corman informed Griffith on a Friday, two days before shooting was set to commence on Monday, that he would have to essentially blow up the script and start over, pushing all the musical performances to the front of the picture (-- filmed later as pickups), opening up the last two acts for some new characters and story arcs.

Now, I’ve never seen the original version of The Little Guy but the IMDB details are solid enough to make me believe the characters and the whole subplot concerning Julie and Sir Bop were added wholesale over that hectic weekend by Griffith.

According to an interview with Aaron Graham for Senses of Cinema (April 15, 2005), Griffith revealed, “I cut it up with a pair of scissors, this original screenplay, and added new characters like Sir Bop.” He then started pasting in these new characters as he rearranged things and then glued it all back together.

“Of course, no songs were written in 24 hours,” said Griffith. “I would just put down ‘musical number here.’ The girl has her dialogue with the guys and then turns around to sing a song. It was up to them what she sang, up to Roger.”

As written, both Corman and Griffith had hoped noted comedian Sir Lord Buckley would play Sir Bop. Lord Buckley was the creation of Richard Buckley: “a hipster bebop preacher who defied all labels” according to musician Bob Dylan, whose gonzo style and speech patterns anticipated aspects of the beatniks (one could argue Lord Buckley was the original beatnik) and influenced people ranging from Lenny Bruce to Wavy Gravy.

Buckley seemed game but once again scheduling conflicts prevented him from being in the picture; but he was amiably replaced by Mel Welles, a comedy writer for Buckley, who essentially imitated his boss in the picture to great effect. Welles even wrote up a Hip Dictionary -- a “Hiptionary” -- to be handed out in theaters to help translate his jive.

Making her screen debut, Abby Dalton was also cast in a hurry to play Julie. But I do believe that’s Nora Hayes, another one of Ram’s clients, that she’s lip-syncing to. (This is backed up by the credits.) These changes also lent to a near alternative title for the film, Rock ’n’ Roll Girl. Now, Dalton would also provide another pivotal piece of Corman’s burgeoning legend of unearthing talent.

“This was the first picture that Abby Dalton did for me,” said Corman (Franco, 1978). “I met her through a friend of mine, and I thought she was tremendously pretty. Abby introduced me to Jeff Corey, who I studied with for acting. I was very pleased with her work.” Of course, studying with Corey was where Corman unearthed Jack Nicholson. Dalton would star in three more Corman pictures in 1957 -- Teenage Doll, Carnival Rock (1957) and the marquee busting The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent (alias Viking Women and the Sea Serpent, 1957). She would also date Corman for a spell.

“Roger and I dated on and off for about a year,” said Dalton (Corman, 1990). “He was a fun, wonderful date; a tall, broad-shouldered, very handsome man with a wonderful smile and a great sense of humor. He was quite attentive and sweet. You always knew where you stood with him. Sure, I had fantasies of ending up with him, but it never happened. I think we both realized it wasn’t going to work out for either one of us. I think Roger was dating half a dozen other actresses at the time and I dated others. I was not the woman he was looking for. I was too wild and flighty.”

Mention should also be made of the wonderful performance of Robin Morse as Al; the dour sour-puss bartender with an answer for everything. I love the barbs thrown between him and Richard Cutting, the reporter, on the woes of bartending. (Tragically, Morse would be dead within the year.)

The rest of the cast was rounded out by Corman’s gradually cementing cast of stock players: Ed Nelson, Beach Dickerson, Jonathan Haze, Barboura Morris, Bruno VeSota, and even Russell Johnson before he took off on one of the longest three hour tour of ever, who actually makes for a pretty good heavy.

“Attack of the Crab Monsters and Rock All Night were the two films I did for Roger Corman,” said Johnson in an interview for the Archive of American Television (2011). “Boy, that Roger was an interesting man. He was making movies for 50 thousand bucks, 60 thousand bucks, 100 thousand at the most. He had a crew of maybe eight guys, and each one of those guys did eight jobs. It was so illegal (as far as the unions were concerned) you’d never believe it. No. It wasn’t illegal. It was just … irregular. But! It was a job. You took what you got. (And) you had to know what you were doing. You had to know your work. You couldn’t come in and stumble around, believe me, there wasn’t time for any of that. Roger was smart. He knew who could handle this type of work.”

As for his directing style, “Corman was a no-nonsense guy. There was no sitting down and discussing what was really going on in a scene between the characters. No time for that,” observed Johnson (Here on Gilligan’s Isle, 1992). “The only direction he gave was ‘You gotta get out of the way of these crabs ‘cause they’re gonna kill you. That was it.” Still, “I have to admit, Roger did some amazing things with what little he had. With such piddly budgets and small crews, he was forced to improvise.”

And then there’s Dick Miller, who took the lead when Dane Clark also proved unavailable to reprise his role. And here, the Jonathan Haze connection strikes yet again. (And at this point, I think it would be interesting to do a giant flowchart to see just how many people Haze managed to draw into Corman’s web).

Like Griffith, Miller had wanted to be a musician after he got out of the Navy, playing the drums and guitar in his native New York, until he busted his guitar over someone’s head. In 1952, he followed his friend Haze to California, who introduced him to Roger Corman.

Jonathan Haze (left), Dick Miller (right).

“I came west from New York to be a writer,” said Miller (Corman, 1990). “I beached it for a year and a half before anything happened -- sold short stories, did one page outlines for a Science Fiction anthology, partied. Then my New York buddy Jonathan Haze told me he had just done his first picture -- an undersea monster flick with a guy named Corman,” which was, of course, Monster from the Ocean Floor (1954).

“So he brought me to Roger’s office over the old Cock ‘n’ Bull.” And their conversation went something like this. Roger asked, What do you do? Miller said, I’m a writer. Need any scripts? No, said Corman. I’ve got scripts. I need actors. Fine, said Miller. I’m an actor. “That’s exactly how it went.”

(Miller and Haze on the left.)

Miller’s first feature for Corman was Apache Woman, where Miller infamously played a cowboy and an Indian on both sides of a shoot-out. “I just about shot myself in the end because I was part of the posse that was sent out to shoot my Indian. Everybody doubled for Roger’s pictures.”

Corman then showcased the actor in several films; and while Miller appeared to be ready to break-out after a few cult hits, mainstream success always seemed to elude him.

I’ve often suspected an undercurrent of professional jealousy involved here. When Corman started getting some positive notices -- especially by the foreign press, a lot of them singled out Miller’s craft and constant scene stealing. But with Corman, I do believe there’s only room for one captain on that ship and Miller, to my eye, soon found himself shuffled into the background.

But, that ship hadn’t quite sailed yet with Rock All Night, and Miller gives a tight and terse performance as Shorty; an oddball anti-hero that I honestly wouldn’t blame anyone if they went ahead and popped him in the mouth as he keeps riding Jigger, pushing him into confrontations with all the other men in the bar; the stereotypical tough guys -- the trucker, the mobster, the boxer, who all wilt from the threat of violence.

And these men also get a venomous earful from Shorty for their perceived lack of guts. And yet, no matter how much he chides him, Jigger -- nor the rapidly melting-down Joey -- can bring themselves to shoot someone who actually stands up to them.

Yup, only Shorty and Julie show any kind of backbone during this stand-off: Julie finding her voice, and Shorty showing only he has the guts to cash the checks his mouth constantly writes, backing down Jigger, taking his gun away, perhaps too easily, and then decking him with one single blow, officially bringing this crisis to a rather abrupt end.

Meantime, all the other personal melodrama around them wraps up in a helluva hurry, too, as the cops take the felons away: the Kid quits the ring much to his wife’s relief; Al stands up to the extortionist and rats him out to the cops; and Julie officially pulls the plug on her singing career much to Sir Bop’s dismay.

Besides, she can’t stick around to sing; she’s finagled herself a date with her new hero, Shorty. And together, they head off for a screening of King Kong, where a bunch of little guys knock a giant gorilla off a really tall building. Coincidence? I think not.

The Wichita Eagle (July 17, 1957).

Released on an AIP double-bill with Eddie L. Cahn’s Dragstrip Girl (1957), "Both are aimed at teenagers like a loaded gun," observed The Los Angeles Times (April 25, 1957). "For anyone who likes rock and roll music there's plenty of it. For drag-race fans there are plenty of hot rods on the bill. These two features have all the excitement of a late afternoon game of shinny played on the Hollywood Freeway." Don't worry, I have no idea how to play shinny either.

"Shorty, played by Dick Miller in Rock All Night is the little 5-footer who carries a chip on his shoulder because of his size. The writers, Griffith (script) and Harmon (story) expect the viewer to accept Shorty as the hero on their own say-so. As to whether or not he has proved his point and has truly earned the affection of Julie (Abby Dalton) after 65 minutes of furious performance is moot."

The Union Banner (June 27, 1957).

Meanwhile, Art Cullison declared the double features as candidates for "the poorest done pictures of the year." (The Akron Beacon Journal, May 2, 1957.) "There's supposed to be some kind of moral but just about the only lesson offered is to stay away from such films," said Cullison.

"Both pictures were ground out on a shoestring to make a fast buck. Performances are wooden. Direction is almost nonexistent. [And] the stories have about as much originality as the excuses a husband offers when he comes home late. The plots are trite and the attempts at humor are unfunny." And then this 'rave' concludes with, "If any youngsters have any desire to kill themselves they can get some lessons in how to do it in these pictures."

Rock All Night would be only one of seven films Corman directed and produced in 1957 -- Naked Paradise, Attack of the Crab Monsters, Not of this Earth, The Undead, Teenage Doll, Carnival Rock, Sorority Girl and Viking Women and the Sea Serpent. And it also might be one of his shortest, clocking in at a scant 62 minutes. But it might’ve been better served if it had reached the magic / golden 70 minute mark.

I checked the timer and from the cool as hell opening animated credits (-- another treat courtesy of either Paul Julian or Bill Martin --) to when Jigger guns down the concerned citizen, which marks the beginning of the plot proper, we’ve already reached the 42-minute mark. Before that, it’s essentially all padding as Corman gets those musical acts out of the way in the first half hour. And since he was pressed for time, Corman had the acts lip-sync to their music and, alas, in the finished film it never does quite sync-up.

I already knew the Platters were good, but was pleasantly surprised by the rockabilly sound of The Blockbusters, who provided the catchy title tune. And once they’re all tucked away at the 35-minute mark after Julie bombs her audition, that leaves us about five minutes to be introduced to everyone else before the shit hits the fan. And once that happens, it leaves barely twenty minutes for the second AND third act. And that’s why I think those extra eight minutes might’ve come in handy.

Either that, or cut into those 35 padded minutes and give those second and third acts a little more room to breathe as I felt Jigger’s capitulation to Shorty felt a tad rushed, robbing the film of any big emotional payoff. That, and the fact that Shorty, even though he is the designated hero, is still one massive dickhead. And if it was anybody but Dick Miller playing him, I probably would’ve been openly rooting for Jigger to just shoot him and let Al or even Julie be the hero.

Thus, the dissonance between the glacial pace of the first chunk of Rock All Night and the errant rocket ride of the final bite does take a bit of adjustment but the reward, if you can pull this off, is worth it, I think.

I’m not sure if cinematographer Floyd Crosby gets enough credit for Corman’s early successes. Crosby, who shot From Here to Eternity (1953) and won a Golden Globe shooting High Noon (1952), was never officially on the Hollywood Blacklist, but he did find himself on the unofficial Greylist which found him equally shunned by the major studios. But, he landed on his feet with Corman and would go on to a long career shooting for him and several other minor studios like AIP or Allied Artists, adding a lot of visual weight to these no-budget wonders.

Here, with Corman’s usual hands-off approach with his actors -- meaning getting out of their way and letting them do their thing with Griffith’s crackling and humorous script, I think it was Crosby who truly established the sparse, economical look and feel of films like Rock All Night, The Cry Baby Killer (1958) or Machine Gun Kelly (1958).

But Crosby maximizes these minimal locations (I believe there were two) as best he can, making a whole lot out of nothing, giving everything a nice noirish flare. Love the lighting when Julie is forced to sing from the shadows; or the staging when Jigger guns down the stranger as the man runs himself into a tight close-up as the bullets rip into his back before he falls out of frame. And this, I think, is what gives these early Corman films their palpable energy.

Still, credit where credit is due as Corman was the one who pulled all of this together and put everyone in place to pull it off: Griffith on the script, Crosby on camera, and Miller in front of it. And it was this kind of no-budget, set-bound thriller like Rock All Night that kinda set the stage for future -- and more ghoulishly mordant -- features like A Bucket of Blood (1959) and Little Shop of Horrors (1960), where Corman took this kind of cheapskate filmmaking and turned it into a true form of art that, I think, started right here at Al’s place.

“Rock All Night was a picture that I personally have always liked,” said Corman (Franco, 1978) “I shot it in six days on a set that was leftover from another film.” And to pull that off, “To get the film shot within a week, I’d go all day with just the lunch break, then shoot till dinner time. Then after a bite to eat, I’d work on the next day’s shots and production problems, get a few hours sleep and begin again the next day.” (Corman, 1990).

“One of the constant little debates with Roger is everyone’s attempt to get him to upgrade his product,” said Griffith (Franco, 1978). “I think everyone at one time has tried to do that -- tried to talk him into moving into a higher category. So in 1956 we had a discussion in the Hamburger Hamlet about doing a comedy and he said, ‘No, no, we can’t do comedy or drama -- because you have to be good.’ Therefore we could only do action pictures, which didn’t ‘have to be good.’ So that helps him to resist all these ideas.”

According to Beverly Gray (Roger Corman: an Unauthorized Life, 2004), “When Griffith handed in a story outline for A Bucket of Blood, about a nebbish who finds recognition in hip art circles after exhibiting his plaster-covered murder victims as sculpture, Corman was first put off by its comedic overtones.” But he was eventually swayed when Griffith pointed out that since this was just another five day wonder horror quickie for $35,000, what would he have to lose by taking a chance at something different?

Apparently, according to Griffith and several others, Corman always balked at comedy because he was too analytical to understand it properly. He could never tell if audiences were laughing at his pictures because they were incompetently bad or laughing with them because they were genuinely funny and found this off-putting. And when he finally agreed to do Bucket of Blood as a comedy, he had to ask Griffith, “How do you direct comedy?” His answer was to make sure “the actors played the nonsense straight, which, of course, made it work.”

This advice worked out splendidly on both A Bucket of Blood and The Little Shop of Horrors -- an unfathomable two-day / three night wonder, and Creature from the Haunted Sea. Alas, not long after, the two-punch combo of Corman and Griffith was destined to fall apart.

In another interview with McGee (Fangoria, No. 11, October, 1981), he asked Griffith about the problems and shortcomings when it came to translating what he had written compared to what actually showed up on screen. “Your image is perfect to your taste,” said Griffith. But, “You can’t realize it, especially with those schedules and budgets. It got to be a bitter joke that Roger would always cut your best scenes. When you get in a hurry, the bare boned plot is all there’s time to shoot. A director would get behind and start throwing out pages. [And] I was beginning to realize what they were ALL going to look like.”

The bad blood actually began to percolate back in 1958, when Griffith’s lawyer, Art Sherman, convinced Gordon Stolberg, vice-president of Columbia Pictures, that Griffith was the ‘straw that stirred the drink’ when it came to Corman’s successful pictures. Said Griffith (Senses of Cinema, 2012), “Roger thought I told them that I taught him everything he knew, whereas it was actually the other way around.”

Columbia signed Griffith to a two picture deal to write and direct Ghost of the China Sea (1958) and Forbidden Island (1958), but he was soon in over his head. The first film went so far over schedule that Columbia sent Fred Sears in to direct the second. “[They were both] really terrible,” Griffith confessed to Dennis Fischer (Chuck Griffith: Not of This Earth, 1997). “It stopped me for twenty years from ever directing again. They were really rank. You see, I got chicken and started to write very safely within a formula to please the major studios, and of course, you can't do that."

After this humbling debacle, he limped back to Corman, where they reconciled over a trip to South Dakota for Ski-Troop Attack (1959) and Beast from Haunted Cave. But then things fell apart again, when Corman decided it was time to move on from these cheap black and white double-bills to lavish Gothic tales of color.

“I thought we’d move up as a group,” Griffith told Gray. “But when Roger moved to the Poe pictures, he dumped all his old writers, who were clearly small-town types without actual futures.” Here, Griffith was replaced by Richard Matheson for House of Usher (1960), The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963).

“[Corman] said that Matheson had a reputation,” Griffith told McGee (Fangoria, 1981). “They were going to go with color and CinemaScope. It was irritating because I saw that he was making a value judgment based on how much people were making and he was the one making (payment) policy. He said that no screenwriter who gets less than $50,000 a script was any good.”

As for the Legend of Roger Corman, “I think his main talent is inspiring a search for ideas on the part of people who are working for him,” said a bitter Griffith (Franco, 1978) “And his main flaw is squelching the same ideas when they come up.”

“The volatile relationship between Griffith and Corman stems partly from the years in which Chuck felt his work was unappreciated or undermined by others,” noted Gray. “He cites, for instance, his discarded screenplay for The Trip (1967), for which Jack Nicholson was eventually credited as writer, and an unproduced comedy version of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Gold Bug.”

Gray referred to Griffith as “a passionate believer in the hallucinogenic properties of LSD.” But Mel Welles told her "Corman didn’t have the nerve to make The Trip the way Griffith wrote it,” opening the door for Nicholson. Welles also maintained that “despite Griffith’s undeniable talent, he was a free spirit who lived life as he chose, wrote at his own pace, and could not always be counted on to fulfill Corman’s instructions.” And though sympathetic to Griffith’s hurt feelings, Welles was convinced that “Roger was remarkably tolerant of Chuck’s foibles.”

“Ten months of writing this script (for The Trip),” said Griffith (Senses of Cinema, 2005). “At first, Roger wanted a dramatic picture with all the social issues of the 1960s in it. So, of course, I wrote a telephone book! I didn’t like it and Roger didn’t like it, so he just asked me to do what I would have liked to do. I told him to make it a musical, because the music coming out in 1967 was fantastic. That old rock and roll shit that we hated had now become brilliant, and we could have made a great musical out of it.”

Now, “Roger wanted to reveal the mental properties or aspects of drugs on the brain, not in a clinical way but in a musical comedy way – a lot of comedy. A lost guy looking for his girlfriend [was] the entire picture. He gets himself high, turned onto all these different drugs and different relationships with people. For instance, his father bails him out when he’s caught drunk driving, but not when he’s high on pot. The social element was there, but mostly it was a musical comedy,” said Griffith.

“Finally, Roger told me ‘I can’t do this. This will sell dope to 50 million people!’ I just left the project. Jack Nicholson came in and did his draft that became the picture. Roger had forgotten everything on our acid trip up in Big Sur (-- yet another wild production tale for another day). [The finished film] was all phonus balonus. The guru was upset because his subject was jealous or afraid. Nothing to do with my original idea. I saw it once in French with no subtitles, but I just hated that picture.”

Thus, Gray concluded, “Griffith may feel he has been taken advantage of by Corman, but Welles holds to the position that Roger was ‘an honest, forthright, truthful business man, who has a little bit of Scrooge in him, a lot of Rupert Murdoch in him, and whose milieu is extremely low budget product, which involves a lot of people getting cut rates on their salaries, getting overused and in some cases abused, thereby creating a little bit of -- or a lot of -- resentment.’”

Still, despite the falling out, Corman remained loyal to Griffith, who would go on to write several more genre staples for Corman’s Outlaw Biker cycle -- The Wild Angels (1966), though Peter Bogdanovich claims to have rewritten most it, and The Devil’s Angels (1967).

He would also join Corman at New World in the 1970s, where he penned Corman’s most successful picture to date, Death Race 2000 (1975); Griffith would also write and direct the Ron Howard vehicle, Eat My Dust (1976), another hit, making way for Howard’s directorial debut, Grand Theft Auto (1977); and would polish off the 1970s directing one of Corman’s JAWS (1975) knock-offs, Up from the Depths (1979).

But then things would fall apart again, again, in the 1980s with Frank Oz’s adaptation of Little Shop of Horrors (1986), which was based on the off-Broadway musical by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, which debuted in 1982, and was a smashing success. The show quickly moved to Broadway proper and is still out on the road to this very day, including my local little theater, who just produced it last year (2023).

Now, back in 1960, as the legend goes, Griffith and Corman went bar-hopping, got drunk, got in a fistfight, and cooked up an idea where a timid clerk fed his customers to a man-eating plant, resulting in their quickest, cheapest, and most threadbare Corman production to date.

Griffith was paid $800 for his script on Little Shop, but threw in the voice of Audrey Jr. for free. (He would also play the burglar who gets fed to the voracious plant.) And while he was getting residuals from the musical, some copyright snafus led to him getting shut out while Corman still got paid by Warners for the new film version, which led to several lawsuits and more resentment.

"It took forever, but the Warner Brothers remake was held up by the case so they settled," Griffith said in 1999 (The Independent, October 8, 2007). "I get one-fourth of one per cent, and it has kept me going since 1983." Unfortunately, Oz’s film version fizzled and technically never went into profit. At least not for a while. Said Griffith, "The original broke even in the first hour of release.”

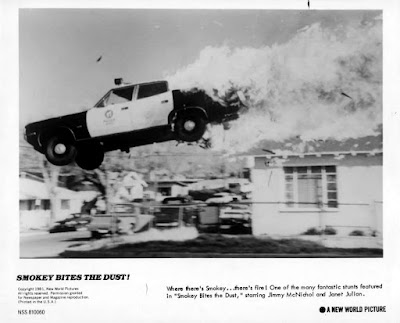

But time heals all wounds, mostly, and Griffith and Corman would remain close (but wary) until Griffith’s death in 2007. He would finish off his career in filmmaking by directing Smokey Bites the Dust (1981) and Wizards of the Lost Kingdom II (1989).

As for his career shortcomings, Griffith became more philosophical and self-reflective with age, time and distance, putting most of the blame on himself. "I was lazy", he admitted to McGee (Fangoria, 1981). "Instead of trying to write an A-picture and sell it on the market, I'd just go back and get another assignment from Roger."

“He was very creative,” said Hayes (The Los Angeles Times, October 3, 2007). “He wrote really funny dialogue, and he was fast -- really fast ... He would write a screenplay in a couple of weeks. Chuck was very good, and very good for that time in film history. He was an innovator. He thought up those really funny, really squirrelly ideas -- like the plant that eats people.”

“[He was] a good friend and the funniest, fastest and most inventive writer I ever worked with," said Corman in a later interview with LA Weekly (April 20, 2014). “His offbeat humor was undoubtedly a big part of the reason a few of my early films acquired 'Cult Classic' status. We had a lot of fun working together to come up with these stories."

And not to belabor the obvious, but, we also had a lot of fun watching them, too. Rock on, boys. Rock on all night.

Originally posted on April 6, 2018, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

Rock All Night (1957) Sunset Productions :: American International Pictures / EP: James H. Nicholson / P: Roger Corman / D: Roger Corman / W: Charles B. Griffith, David P. Harmon (teleplay) / C: Floyd Crosby / E: Frank Sullivan / M: Buck Ram, Ronald Stein / S: Dick Miller, Abby Dalton, Russell Johnson, Robin Morse, Mel Welles, Richard Cutting, Jeanne Cooper, Chris Alcaide, Jonathan Haze, Barboura Morris, Beach Dickerson, Clegg Hoyt, Richard Karlan, Bruno VeSota, Ed Nelson

%201957.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-14.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-18.jpg)

%201956.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%201957_02.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-21.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-20.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-02.jpg)

%201957_07.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-11.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-22.jpg)

%201957_06.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-19.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-09.jpg)

%201957_01.jpg)

%201957%20RAN-04.jpg)

%201957.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment