Our film opens in the midst of the Cuban revolution as interpreted by artist Paul Julian, who gives us yet another nifty opening animated credit sequence. And with the fall of Batista imminent, several of his Generals abscond with a good chunk of the national treasury and arrange to sneak both it and them out of the country with the help of that American expatriate, gambler, and all around no-goodnik, Renzo Capetto (Carbone).

Also along for this clandestine ride is Capetto's deviously deadly mol, Mary-Belle Monahan (Jones-Moreland), and the motley crew of his cabin-cruiser / Tardis (-- judging by how much room there is inside that thing); a trio of boobs who probably wouldn't pass muster on the S.S. Minnow.

We start with Monahan's idiot younger brother, Happy Jack (Bean); followed by the idiot first mate, Pete Peterson (Dickerson), who, after a rash of severe cranial traumas, mostly communicates with wild animal calls.

And rounding things out is another idiot by the name of Sparks Moran (Towne, credited as Edward Wain), who just so happens to be an undercover government spook sent by the CIA to keep tabs on Capetto; and who also has a knack for making communication devices out of knick-knacks and kitchen condiments -- that Peterson keeps eating.

Anyways, after they set sail, having lost his gambling interest to Uncle Fidel and the Fuller-Brush Beard Brigade, Capetto aims to even-out those losses by stealing the treasure out from under his charter. To do this, however, he must first thin out the dozen or so Cubans on board first.

And to do this without raising suspicions, Capetto comes up with a hair-brained scheme to concoct a monster, based on the old Hemingway legend, to take the blame for the impending fatalities. (Wait, you say. The Old Man and the Sea Monster? Really? Yeah, well, just roll with him.)

Thus, with the help of a couple sharpened hand rakes and a handy plunger, Capetto's plan commences without a hitch -- that is, until a real monster shows up and starts clandestinely munching on his passengers, too…

Sometime in the late 1950s, Roger Corman found himself staying in Havana, Cuba. He was there at the invitation of Lawrence and David Woolner, a couple of drive-in theater entrepreneurs, who had financed Swamp Women (1956) and Teenage Doll (1957) for Corman as The Woolner Brothers.

The Woolners were there to meet with a Cuban film company over the possibility of importing and releasing some of their films in the States -- like they would do later with several Italian pictures like Hercules in the Haunted World (alias Ercole al centro della terra, 1961), Castle of Blood (alias Danza Macabra, 1964), Castle of the Living Dead (Il Castello dei Morti Vivi, 1964), and Blood and Black Lace (alias Sei donne per l'assassino, 1965).

Now, those who remember their social studies classes will recall that this was a particularly volatile period in Cuba’s history, and Corman and his hosts were about to find themselves stuck in the middle of a revolution.

“I was sharing a suite at the National Hotel with the Woolner brothers, who were interested in doing some work with a company called Cuban Color Films,” Corman recalled to J. Philip di Franco (The Films of Roger Corman, 1978). “In the middle of the night I heard what sounded like a car backfiring and went out onto the balcony. The National was located in a park and across the park was a string of restaurants and nightclubs, and it was clear there was machine-gun fire going on there,” said Corman.

“When we came down for breakfast the next morning we asked the maitre d’ what happened, and he said, ‘Fidel Castro’s men came in and killed the chief of police and a number of other people coming out of a nightclub.’ As we were driving out to the Cuban Color Film offices that morning, Batista’s men were patrolling with machine guns. We stopped at a payphone, called the travel bureau back at the hotel, and got on an afternoon flight to New Orleans.”

Quite the experience, for sure; but who could’ve possibly foreseen that these harrowing events would inadvertently lead to one of the funniest films Roger Corman would ever produce?

In the early stages of his career, Corman had always balked at doing anything remotely humorous, despite the best efforts of Chuck Griffith, his frequent screenwriter, trying to sneak something in. Why? Because he feared they didn’t have the means or talent to pull it off properly. He was never sure if audiences were laughing with him or laughing at him. According to Griffith, as reported by Beverly Gray (Roger Corman: An Unauthorized Life, 2000), Corman’s mantra at the time was, “We don’t do comedy or drama, because you have to be good. We don’t have the time or money to be good, so we stick to action.”

And this had served him well, at least to that point. “Corman’s movies stood out from the other low-budget films of the era because they always gave the viewer something extra: a clever idea, a distinctive performance, a modicum of style,” said Gray. And Ian Spear (Boxoffice Magazine, 1956) added, “A refreshing new type of producer-director, the young Corman is gifted with imagination, daring, and entirely unhandicapped by the do’s and taboos over which many more experienced film fabricators are currently stubbing their financial toes.”

But Griffith kept trying, sneaking in a few comedic elements like Dick Miller’s hippy-dippy vacuum cleaner salesman into Not of this Earth (1957). Then, one fateful day, Corman took Griffith to a studio where the sets for Burt Topper’s Diary of a High School Bride (1959) were still standing and would remain standing for another week.

“He told me to write a horror picture with these sets, which consisted of a beatnik coffee house, a jail, and an apartment. I wrote something called The Yellow Door, but when I handed him the first 20 pages he was furious because it was [written as] a comedy,” said Griffith (Fangoria Magazine, No. 11, October, 1981).

The darkly humorous satire concerned a poor schlub named Walter Paisley (Dick Miller). Paisley works as a lowly busboy at The Yellow Door, an art house cafe, who suddenly becomes a cause célèbre in hipster art circles when he exhibits the macabre plaster-covered remains of the people he’s killed in situ. (The first victim was an accident, the others, well, not so much.) And with a little pushing, Griffith was finally able to convince his boss to take a chance.

“I told him he was going to make the picture for thirty thousand in five days so how could he lose? [Then] he said he didn’t know how to direct comedy, and I told him to just play it straight.” (Fangoria, 1981.)

Griffith’s advice worked out splendidly, and as the cameras rolled on the rebranded A Bucket of Blood (1959), when Julian Burton completed his beatnik poetry slam that opened the film, the cast and crew erupted in applause. Here, according to Griffith (Fangoria, 1981), “Roger became very excited. He pulled me to one side and said we’ve got to do another [horror-comedy] right away. He didn’t want to do a sequel or anything. [But] he wanted exactly the same picture.”

Said Gray, “Corman’s own accounts of the filming of A Bucket of Blood have downplayed Griffith’s role in instigating the project, focusing instead on the challenges of a five-day shoot. The AIP film, though a favorite of many Corman film buffs for its biting satirical edge, certainly betrays its quick-and-dirty schedule and ultra-low budget. In an era when others were embracing color and wide-screen technology, the 66-minute feature was shot in glorious black and white.”

With this most likely being the best role he ever played, Miller also wished that a little more time and money had been expended on the picture. “If they had more money to put into the production so we didn’t have to use mannequins for the statues, if we didn’t have to shoot the last scene with me hanging with just some gray makeup on because they didn’t have time to put the plaster on ‘em, this could have been a very classic little film,” said Miller (Gray, 2000). “The story was good, the acting was good, the humor in it was good, the timing was right, everything about it was right -- but they didn’t have any money for production values, and it suffered.”

“These horror comedies marked something of a departure from Corman’s early pictures because of their accent on dark humor,” noted Gray (2000). “Though Corman can show a sly wit in conversation, most who know him agree he is a fundamentally serious person who prefers making serious movies.”

Thus, “Those acquainted with the early films of Roger Corman agree that [these hybrids] were aberrations; [future employee and film director] Joe Dante cites the legend that Corman needed to have the script’s humor explained to him. [But] the consensus is that the guiding spirit behind these films was writer Charles B. Griffith, whose talent for outrageously mordant comedy came to full flower in this period (1959-1961) -- and the flower was something of a Venus flytrap.”

But that second hybrid-comedy Corman wanted would have to wait as Griffith got slightly detoured by an offer from Columbia Pictures to write and direct a series of films on his own, which ended in disaster -- a disaster we covered in more detail in our previous review of Rock All Night (1957).

Meanwhile, Roger teamed up with his brother, Gene Corman, and formed their own company, The Filmgroup, in 1959. This was their initial effort to cut out the middleman and produce and distribute their own films, removing anyone else’s dubious accounting practices from the equation, and keep all the money themselves.

Thus, odds are good Corman was in Cuba with the Woolners to see what he could possibly pick up and distribute as well. And while Corman never did import anything from Cuba, he did snatch up several Soviet Cold War Science Fiction epics, including Nebo Zovyot (alias The Sky Beckons, 1959) and Planet Bur (alias Planet of Storms, 1962).

Quite infamously, Corman’s litmus tests on a number of his soon-to-be-famous underlings was to cannibalize the lavish special effects from these features and turn them into Americanized Creature Features.

Francis Ford Coppola would re-edit Nebo Zovyot into Battle Beyond the Sun (1962), where he notoriously punched it up by adding a staged battle between two ‘giant’ monsters that were obviously inspired by human genitalia -- one male, the other female. And Peter Bogdanovich added Mamie Van Doren as a psychic mermaid when turning Planet Bur into Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women (1968).

But Filmgroup’s opening salvo was a pair of double bills: the first was two pick-ups concerning hot-rods and juvenile delinquents with Joel Rapp’s High School Big Shot (1959) and Richard Harbinger’s T-Bird Gang (1959); and the second, two in-house tales of Science Fiction. The top of that bill would be The Wasp Woman (1959), directed by Corman, where a cosmetic executive (Susan Cabot) becomes a were-insect in her search for eternal youth.

As for the second Sci-Fi feature, the Cormans would head to the Black Hills of South Dakota, near Deadwood, in the dead of winter, to film two features using essentially the same cast and crew to save and maximize their money, which soon became their modus operandi. South Dakota was a right-to-work state, meaning they could shoot nonunion without any hassles. And it wasn’t so much that Corman worked with nonunion guys, but to keep costs down his minimal crews of six or seven did the jobs of twenty to thirty, which was a big no-no to the IATSE.

There, Roger would produce and direct Ski Troop Attack (1960), a War film, and Gene would produce Beast from Haunted Cave (1960), a Creature Feature and eventual partner of The Wasp Woman, which would be directed by Monte Hellman, a recent graduate of UCLA’s film school.

“I first met Roger through my wife, Barboura Morris, who had acted in some of his movies,” testified Hellman in Chris Nashawaty’s Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses (2013), a delightful collaborative oral history on Corman’s career. (Highly recommended.) Morris was another Jeff Corey find for Corman, who pilfered his acting class for a lot of talent. She starred in A Bucket of Blood, Sorority Girl (1957) and Machine Gun Kelly (1958) among others for Corman.

At the time, Hellman and Morris were trying to stage a production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and were in need of funding. Said Hellman, “ I got Roger to invest in a theater company that we put together. Eventually, we were shut down, and Roger said, ‘You should take this as a sign and do something else.’ He hired me on the spot to direct Beast from Haunted Cave. He paid me $1000. We didn’t have a contract or anything. Just a handshake. And Roger’s handshake was better than most people’s contracts.”

As for working for Gene Corman, “Gene’s a lot of fun. A good guy,” said Hellman. “Not quite as tight-fisted as Roger -- but almost. We shot in South Dakota, and it was below zero. I think we had Velveeta sandwiches for lunch everyday on the set. Pretty luxurious. Velveeta sandwiches and a cup of hot chocolate. That was a big deal.”

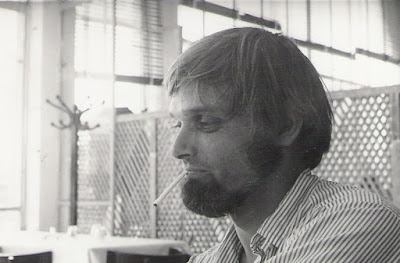

Monte Hellman.

Said Gray (2000), “Though Gene Corman was credited as producer on Beast from Haunted Cave, those involved agree that, as always, Roger took charge of the whole enterprise. His aim was to keep the budgets at $50,000 or below.”

Hellman would later recall for Gray how “Corman told everyone in town that we were UCLA film students doing a student film, so we got hotel rooms for, I think, a dollar a night; but we had two people in a room so it was fifty-cents a night per person; and we were shooting in ten below zero temperatures and (according to this account) he served salami sandwiches on plain white bread for lunch. I thought, ‘If we just had a cup of soup…’”

With his solo efforts ending in shambles, Griffith would slink back into Corman’s good graces and would provide the scripts for both frozen features. “Well, I knew something about the Battle of Hürtgen Forest (one of the bloodiest battles of World War II), so I used that [as the basis for Ski Troop Attack],” said Griffith (Senses of Cinema, April, 2005). The plot involves a reconnaissance patrol that disobeys orders and winds up destroying a railroad bridge to thwart a German counterattack.

“Roger wanted a train,” said Griffith. “They blew up a train and bridge in that one. It was a pretty bad script. I remember [hardly anything] about that film but Roger skiing with the local ski club in Deadwood, North Dakota (sic). All these teenagers who were playing Nazis, you know?”

“Ski Troop Attack was shot in ten days in the Black Hills of South Dakota,” said Corman (Trailers from Hell, November 19, 2013). “The problem was, the day before we were to shoot, we had a German skier playing the leader of the [enemy] and he broke his leg. I didn’t know what to do. So finally I decided to play the role myself as well as direct the picture. I was handicapped for two reasons: I couldn’t speak German; and I couldn’t ski. Other than that, I thought my performance turned out okay.”

As for those teenagers, “For the ski troops, we used the Deadwood high school’s ski team and the ski team from an adjoining high school, who were their rivals; and one of them played the Germans, and the other played the Americans. They got along very well but began to take on the characteristics of each group. The German [players] started to think they were Germans!”

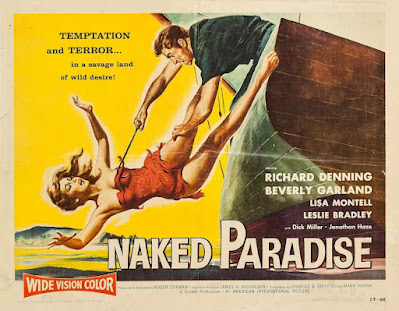

As for Beast from Haunted Cave, Griffith would basically file the serial numbers off of Naked Paradise (alias Thunder Over Hawaii, 1957), an earlier Corman heist film for American International, and use that script again.

Apparently, this was on Corman’s orders, as Griffith remembered it, telling Gray how he was told by his producer to give him “Naked Paradise at a gold mine, with a blizzard instead of a hurricane, and, oh, add a monster.” Odds are good since this wasn’t an original script that AIP already paid for, Griffith would be paid accordingly on the sliding scale of such things.

The Los Angeles Times (March 18, 1960).

Once filming wrapped in the Dakotas and they returned to sunny L.A., after a period of defrosting, Corman and Griffith would once again take up that second horror-comedy. “After we did those South Dakota pictures, we recognized A Bucket of Blood as having a usable structure,” said Griffith (Senses of Cinema, 2005). “That’s the most precious thing you can find is a new structure.”

And from there, as the legend goes, “We went out on the town and started throwing our ideas around. We talked over a bunch of ideas, including gluttony. The hero would be a salad chef in a restaurant who would wind up cooking customers and stuff like that, you know? We couldn’t do that though because of the code at the time. So I said, ‘How about a man-eating plant?,’ and Roger said, ‘Okay,’” recalled Griffith.

“By that time, we were both very drunk.” So drunk, they eventually got into a fight at the Chez Paulette with another bar patron -- none other than Lawrence Tierney, star of many famous noir films and a notorious drunk and barroom brawler. Said Griffith, “Incidentally, Larry Tierney knocked me out, but later became a great friend when I was living in Rome.”

After regaining consciousness and sobering up, Griffith set to work on the script for The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). “I followed the structure of A Bucket of Blood almost exactly, but where Bucket was more of a satire, this would be a flat-out farce with no social commentary,” Griffith testified in Corman’s autobiography, How I made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (1990).

This round, Walter Paisley would be replaced by Seymour Krelborn (Jonathan Haze), a nebbish clerk at a flower shop located along skid row, who is about to be fired. He earns a reprieve from his boss, Mr. Mushnick (Mel Welles), when his latest horticultural experiment, dubbed Audrey Jr., named after a co-worker (Jackie Joseph), starts drawing crowds. The catch, the only thing keeping the plant alive was a steady diet of human blood.

Here, it should be noted that while he enjoyed the production of A Bucket of Blood and its end results, despite some favorable critical reviews, the middling box-office returns on the same had Corman unwilling to expend a lot of time or money on this latest effort.

Helping matters was another production’s office sets were still standing -- another cost-saving favorite of Corman’s. And after finagling a deal to use them for a couple of days, Corman and Griffith set to work and spent the next two days and three nights completing the entire film for about $27,000 -- using actual skid row bums as extras and as members of the crew.

Griffith would serve as the film’s narrator and have a cameo as the robber who eventually gets fed to the killer plant. He would also shoot second unit on the picture on the overnights. And contrary to most reports, this was not the screen debut of Jack Nicholson as the masochistic dental patient; no, he had already appeared in Corman’s The Cry Baby Killer (1958).

The wild, of-documented two-day turnaround on The Little Shop of Horrors has been etched in the bedrock of the monument to Roger Corman’s storied film career and had firmly established his reputation for working (ridiculously) fast and (ludicrously) cheap. However, as film critic Arthur Knight noted (Franco, 1978), “I’ve always been struck by the fact that Roger makes more of a claim about how quickly he can do a film than about how well he’s done a film.”

Said Hellman (Gray, 2000), “Those kinds of economics don’t pay off in the long run. You get a lot of bad will that’s generated.”

Dick Miller also chimed in on this subject of speed over quality, telling Gray, “He was turning out a product that made him money. But at the same time, I used to get an inkling from some of his discussions that he was very sincere and very serious about his work. It’s hard to say [he was] artistic on a picture made for $17,000, but I think he was sincerely trying to make a good movie. There were guys around in those days who said, Let’s make a movie. You get your cheap script and cheap actors, and we’ll make this cheap movie. And Roger, I think, was thinking, Let's get the best we can.”

In her later interviews with Corman acolytes and Corman Film School grads, Joe Dante -- Piranha (1978), Gremlins (1984) -- told Gray, “I don’t know if he was ever an artist, but he was serious about making movies.” And producer Jon Davidson -- Airplane! (1980), Robocop (1987) -- added, “And he made better cheap movies than anybody else.”

“Roger has no patience, and that was his great strength,” said Robert Towne (Franco, 1978). “He has the intelligence and originality of a Fellini or a Truffaut, but let’s say you’re shooting Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and you have in your mind that you want this figure to emerge out of the desert as just a shadow, as just a mirage -- you may have to wait three weeks to get that shot. If you don’t have the patience [of David Lean] to do that, then there’s no point having the discussion. And if Roger can’t do that, it’s not because of a lack of raw talent or intelligence -- it’s because it’s either a character flaw or a virtue, depending on how you look at it. He’s someone who just doesn’t have the patience -- he’s gotta do it fast.”

At the time, Towne was a half-assed actor and would-be screenwriter, who had befriended Corman while both attended Corey’s acting class with the likes of Nicholson, Morris, Irvin Kershner and Sally Kellerman. And this friendship allowed him to be honest with Corman. Said Towne (Franco, 1978), “I think what really was involved is that Roger has a rather mathematical cast of mind and inevitably he gravitated toward that which he could keep score with best. And so things got translated into, ‘I did this movie in five days.’ ‘This movie cost $20,000 and grossed $100,000.’ This was a way of measuring your achievement. I think there was a natural tendency to measure things in the way he knew best -- instinctively best -- which was with numbers.”

The Corman Brothers: (L-R) Gene and Roger.

Ergo, “The texture of a scene is less palpable, less easy to define than numbers. ‘I did this movie in two days.’ There was that tendency to take pride in the skill with which he was able to turn things out so quickly. I think inadvertently he felt that if he didn’t do it quickly he did it wrong,” Towne theorized. “Even when he knew better, he was measuring himself by two standards -- the alacrity with which he was able to do something, and as a man of great intelligence and sensitivity who really wanted to make fine films. I think there was this kind of split in him and so it was exceedingly difficult to take the time to make certain things work a little more carefully.”

And while Towne claimed these were merely observations, and not an indictment, Corman was swayed by his logic. Said Corman (Franco, 1978), “Robert Towne, a good friend of mine, said you have to remember, filmmaking is not a track meet. It’s not how fast you go.” At the time, “I was thinking roughly the same thing” and concluded, “Enough of the two- and five-day pictures. The Little Shop of Horrors was the film that in the long run has made me whatever legend I am at this point.” But it was time to move on. To think bigger and better. But this transition could only be measured by the time spent making his pictures, not what he spent on them.

Around this same time, Corman got wind that there were certain tax shelters to be fleeced if he filmed his latest opus outside the continental United States. Said Corman (1990), “I had discovered that tax incentives were available if you ‘manufactured’ in Puerto Rico. That included making movies.”

In the June 23, 1959, issue, Variety declared Corman had struck a deal with Caribe Films, an outfit out of Puerto Rico, to produce two films. The terms included distribution rights to the U.S. and Canada going to Corman, the Latin America rights going to Caribe, and the rest of the world to be split evenly among them.

Wichita Falls Times (May 4, 1960).

Corman was already headed there on someone else's dime to shoot The Battle of Blood Island (1960) as part of a production deal with The Filmgroup; the intention was to pair it up with Ski Troop Attack for a Combat Shock double feature. The film was financed by Stanley Bickman, and would be written and directed by Joel Rapp. It was based on a Philip Roth short story, Expect the Vandals, which was first published in Esquire Magazine (December, 1958), where an American Marine unit is wiped out by the Japanese and the two lone survivors, who hate each other, bury the hatchet long enough to evade the enemy and survive until help arrives.

And while the newly extended two week shooting schedule allowed for more patience and opportunities to improve the look of the picture, corners were cut everywhere else to compensate, starting with a minimal two-person cast (Richard Devon, Ron Gans -- Corman would have a brief cameo as another soldier who gets killed.) The entire opening battle scene is achieved off-screen with stock footage and sound effects. They couldn’t even afford blanks, and so the actors had to point their weapons and fake the recoil.

Now, Corman’s plan all along was to shoot a second feature using the same crew as Blood Island -- just like he did in South Dakota. “Robert Towne was trying to break in as a screenwriter, so I asked him to write The Last Woman on Earth (1960),” said Corman (1990). “Bob has since become one of the finest screenwriters in the business with scripts like The Last Detail (1973); Shampoo (1975); and Chinatown (1974), for which he won the Best Screenplay Oscar. But back then he worked slowly, an unfortunate fact that would cause me some problems.”

Said Towne (Nashawatay, 2013), “Roger told me I want you to write a script with the title ‘The Last Woman on Earth.’ That’s the amount of instruction I was given. Nothing about the plot or anything else. That’s it.”

Thus, when Corman and his cast and crew were ready to depart for Puerto Rico, Towne hadn’t finished the script yet. He was writing it in longhand because he either didn’t know how to type or couldn’t afford a typewriter. And so, Corman came to a decision: “The only possible way for me to afford to take him down there so he could finish the script was to hire him as one of the actors. He’d have to play the second lead [in the second feature].” (Corman, 1990). Well, he would -- if he ever finished the script, that is.

Meanwhile, this second feature would also have a two week shooting schedule; and so, Corman would continue to cut every corner possible, logistically speaking -- especially in the room and board department for the cross-pollinated cast and crew. He packed them all into a chigger-infested bungalow in the Condado district that had four rooms, each filled with five cots, one malfunctioning toilet, and no food because the fridge was chock full of film stock to protect it from the oppressive heat and humidity.

Jacques Marquette, his director of photography, took one look at this makeshift barracks and opted instead to stay at the Caribe Hilton Hotel. “Now, what happened is that all the people that were staying at the ‘mansion’ came into town on the weekend. They’d come to my hotel and eat dinner with me, and I’d sign the check for all of them,” Marquette confessed in a later interview with Tom Weaver (Double Feature Creature Attack, 2003), meaning Corman would have to pay for all of it.

Now, Jacques “Jack” Marquette is probably a well known name amongst the B-Movie Brethren, having produced, directed or shot things ranging from The Brain from Planet Arous (1957), Teenage Monster (1957), Teenage Thunder (1957) and Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958). He first worked with Corman on A Bucket of Blood, and he would shoot both Blood Island and The Last Woman on Earth.

“He drew up all the contracts and I was to get two percent of each picture’s gross; he didn’t want to pay me, he wanted me to defer. You can’t do that [by union rules]; I had to be paid at least scale,” said Marquette. As for the actual shooting, “Roger gave me complete photographic freedom -- he was too busy with logistic problems to solve. As long as my suggestions did not cost any extra money, it was fine.”

“Some of the cast and crew stayed in the Caribe Hilton Hotel, but most of us stayed in the beach house,” said Corman (1990). “It made the trip feel more like a vacation, except for Bob, who was closeted inside, racing the deadline so we could begin shooting.”

Said Towne (Nashawatay, 2013), “I was living in the rented house there with Roger, and I remember when I first got there, I went to take a shower, and there was Roger with a wet towel whacking hundreds of silverfish that were in the shower, trying to clean it out for me. Roger is nothing if not a gentleman.”

Now, here we’ll pause to point out that while Corman was down in the jungle, he had another unit filming a picture back in the States. “Before leaving for San Juan, I also set in motion another film in Northern California that I would merely finance, The Wild Ride (1960), to be directed by Harvey Berman, a graduate from UCLA’s Theater Arts Department, who now taught drama at a high school and held a film course,” said Corman (1990).

Berman had approached Corman with an offer that he could shoot a film with his students for very little money. “That sounded good to me,” said Corman. The script was provided by Marion Rothman and Ann Porter, based on a story by Burt Topper, which told the tale of a Johnny Varron, “a rebellious punk of the beat generation,” who spends his days as an amateur dirt track driver and his nights partying and troublemaking. Then, things get out of hand when he kidnaps his buddy's girlfriend, which leads to a killing spree and his eventual comeuppance.

Corman would assign Nicholson to star as Varron and Georgianna Carter to play the girl. Also in the cast was one of Berman’s students, Robert Bean. And to help the novice Berman stay on track, he also assigned his art director Daniel Haller, his jack-of-all trades Beech Dickerson to run sound, and sent his current personal assistant, Kinta Zertuche, to serve as a line producer and handle the film’s $30,000 budget.

Zertuche was an English professor at USC, who answered an ad that led to working for Corman, where she would pitch in on the script for The Wasp Woman. She would also appear as Nurse Warren (credited as Lani Mars), who would meet her demise in the film's climax. She would then help handle logistics while on location for Ski Troop Attack and Beast from Haunted Cave.

Once filming wrapped on The Wild Ride, she and Dickerson would fly to Puerto Rico. Bean, meanwhile, asked to tag along, hoping they might have a job for him as an actor or crewmember. And since he was willing to make his own way to Puerto Rico, Zertuche agreed, figuring they could always use him in some capacity.

The Wasp Woman (top) and Kinta Zertuche (bottom).

Production on Battle of Blood Island was well underway when Zertuche and Dickerson arrived in Puerto Rico. (Bean, on his own, would arrive later.) “The night I flew in was incredibly hot and humid,” said Zertuche (Corman, 1990).

Her flight had been delayed and didn’t arrive until 2am. At that late hour, the airport was practically deserted and there was no one there to meet her from the production. “I didn’t know where they were. I had no telephone number. And I had no idea how I was supposed to find them in the whole city of San Juan,” said Zertuche (Weaver, 2024).

She tried to see if any messages had been left for her but the airline’s desk was equally deserted. She did manage to find a janitor, who barely spoke English, and together they found a note crumpled up in the trash, left by Roger, on where she needed to go. And so, “I got a taxi to the house and the lights downstairs were on. There was Bob Towne. ‘I’ve been up all night,’ Bob said. ‘Roger is screaming. He wants me to get this damned script written. I’m doing the best I can.’” (Corman, 1990.)

And so, “I held Bob’s hand while he finished over the next few days and dealt with all kinds of other details,” said Zertuche, including finding a plumber to deal with that toilet. “In Deadwood I had to keep the film from freezing. In San Juan I had to keep it from melting. It was scorching hot. We had to refrigerate the cans until shipping them.”

Finished the day before shooting was set to start (only it really wasn’t), Towne’s script entailed another minimal cast: a wealthy industrialist (Anthony Carbone), his wife (Betsy Jones-Moreland), and his personal lawyer (Towne), who are on vacation in the Caribbean and go skin-diving. But then they surface to a post-apocalyptic world, where they appear to be the last three people left on Earth. And do the math from there, in a biblical coveting sense, as three soon becomes two.

“I think I was the highest paid actor,” Anthony Carbone recalled to Tom Weaver for Fangoria Magazine (No.163, June, 1997). “I got $400 a week. Last Woman on Earth took 10 days or two weeks. Unfortunately, it wasn’t completely written. Well, it was, but new things were being added all the time by Bob Towne.”

(L-R) Richard Devon and Ron Gans.

Originally, Corman had hoped Richard Devon, the star of Blood Island, would also take the lead in Last Woman on Earth. But there was a lot of bad blood between the actor and the producer, most of it stemming from Devon wrecking his knee during a stunt gone awry on Viking Women and the Sea Serpent (1957). It was Devon and Marquette who instigated the initial revolt about staying in the bungalow. And after a particularly bad blow up on set, Devon went home after filming finished on the first feature and Carbone was flown in to take over.

Carbone was also a Corman veteran, having worked with him before on A Bucket of Blood as the paranoid who first realizes the homicidal origins of Paisley’s artwork. On the commentary track for Image Entertainment DVD of The Roger Corman Puerto Rico Trilogy (2006), Carbone talked about how “we didn’t really ad-lib a lot” on these pictures, “but we really didn’t follow the script either.”

Also of note, “Roger was able to get those locations somehow,” added Carbone (Fangoria, 1997). “The government was so high on making films down there that he got a lot of things for very reasonable rates. He made great deals -- Roger’s marvelous that way. If you have to do something, get him in your corner because he’s terrific. I also remember he was using a new type of film from Kodak; film stock that they were trying out, so I think he got quite a bit of it for nothing, or almost nothing.”

Anyhoo, as the shoot for The Last Woman on Earth entered its second week, Corman realized he would have a few extra rolls of half-frozen film leftover and just enough money for another five more days of shooting -- thanks to an infusion of cash bilked from The Wild Ride. Plenty of both to get a third feature in the can.

“Last Woman was a two-week shoot,” said Corman (1990). “It was going so well and we were having such a good time that I decided to do another movie. I would use the same three main leads from the first movie, plus pick up some local Puerto Rican actors. I thought: Kinta will come and put the rest of The Wild Ride money in the account, everyone else is already here, I’m shooting a third movie with leftovers. We called it Creature from the Haunted Sea (1961).”

Now all he needed was a script. And due to the time constraints, he would forgo using Towne. “Roger got me to act in another movie,” said Towne (Nashawatay, 2013). “I didn’t really see myself as an actor. And that movie confirmed my suspicions. It underlined that I most definitely did not have a career as an actor. And I was beginning to wonder if I had a career as a writer, too.”

Instead, Corman would call on the ever-reliable and very speedy Griffith. “I called Chuck in L.A. and woke him up. I told him I needed another comedy-horror film and he had a week to write it,” said Corman (1990). “There was no time for rewrites. I had a small cast so I said write it for them. If he needed more actors then write small roles for Beech Dickerson and me as well. He was very sleepy and I wasn’t certain he understood completely the story line we discussed, but he agreed.”

On

the other end of the line, Griffith would recall waking up one morning

and finding a nearby notepad full of scribbles. (Weaver did the math: a

6am phone call from Puerto Rico means a 3am answer in Los Angeles.) He

tried to read it and eventually concluded that he had received “a call

from Roger in Puerto Rico, where he was shooting Last Woman on Earth.

Roger said who was there -- Beech Dickerson, and so on -- and told me to

do another Naked Paradise, but this time from Cuba. He also said to

make it a comedy and that I had three days. Then he hung up,” said

Griffith (Senses of Cinema, 2006).

Charles "Chuck" B. Griffith.

“Chuck Griffith got conned into writing a rewrite of Beast from Haunted Cave, which was a rewrite of Naked Paradise,” said Dickerson (Franco, 1978). As I said, Dickerson was sort of a jack-of-all-trades for Corman -- actor, extra, stuntman, soundman, set construction, grip, and we covered his career in our review of Teenage Caveman (1958) a while back. “This was the third time he’d written the same script. I think Roger offered him the enormous sum of $500 to do it.”

Thus and so, Corman trotted out the same heist-gone-wrong plot again, again; only this time, fresh off the critical success of the minimalist absurdity of A Bucket of Blood and The Little Shop of Horrors, this third feature would be another backdoor comedy, too.

“Blood Island finished on a Saturday and I started Last Woman on Monday. Two Saturdays later, we wrapped Last Woman and were ready to start Creature the following Monday -- one day of preparation per picture,” said Corman (1990). “Chuck’s script came in on Thursday night before we finished Last Woman. It was clear he hadn’t remembered the storyline we discussed completely.”

“The film had a really weird storyline,” added Corman (Franco, 1978). “I read it Thursday night; rewrote sections of it between takes on the set Friday; had it duplicated Friday afternoon; passed it out and rehearsed it Friday, Saturday and Sunday; prepared the locations on Sunday; and started shooting on Monday.”

Here, Corman put his faith in the hands of a game cast and just let the camera roll. The results were a weird and wonky goof of a film. Granted, not all of the ensuing bedlam works, but there were enough bits of business, I think, to sustain this thing to the bitter end.

But we're not quite there yet. And for that, you'll have to come back for Part Two of our look at Creature from the Haunted Sea to see how Corman managed to pull all of that off with a little esprit de corps and a shit-ton of Brillo pads.

Originally posted on June 18, 2011, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

Creature from the Haunted Sea (1961) The Filmgroup / P: Roger Corman / AP: Charles Hannawalt / D: Roger Corman / W: Charles B. Griffith / C: Jack Marquette / E: Angela Scellars / S: Antony Carbone, Betsy Jones-Moreland, Robert Towne, Beech Dickerson, Robert Bean, Edmundo Rivera Álvarez, Esther Sandoval, Sonia Noemí González, Blanquita Romero

_1.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment