Our nifty little potboiler of teenage hormones and the ever-widening generation gap begins in the “little girl’s room” of the local high school, where Connie Harris, ringleader of the all-girl gang The Hellcats, has apparently called a meeting. Seems there’s a new girl starting school today, and Connie, after lighting up a cigarette in clear defiance of the posted No Smoking sign, wants to see if she’s Hellcat material and worthy of initiation.

But before this newbie can be folded into the group, there's a gauntlet of hazing rituals she must survive first. And when asked which one she’ll begin with, after another long drag off her cigarette, followed by a devilish smile, Connie (Lund) settles on the dreaded “slacks” test.

With that, Dolly Crane (Sidney), Connie’s chief flunkie and a complete mental case, angrily declares that test is too easy, and then punctuates this point by just as angrily tossing her switchblade toward the wall; and when it sticks with a lethal thud, this triggers one of thee greatest spazz-jazz riffs to ever wail, baby, wail, in one of these vintage juvenile delinquent pictures -- courtesy of the great Ronald Stein. A musical motif we will be hearing again, and again, aaaaaaand again.

Anyhoo, cut to a classroom as the first period bell rings, where, much to the girls’ delight, they find a substitute teacher filling in today. Better yet, a male substitute -- teaching Home Economics, no less! Here, as she makes her way to an empty desk, the new girl, Joyce Martin (Lime), watches as the overwhelmed substitute tries to get the others to take their seats; to which Connie replies, “Where should we take them, teacher?” Classic.

Things pretty much degenerate from there, with the gathered Hellcats raising such a ruckus it sends the poor substitute galumphing off to the principal’s office for reinforcements. Telling one of her stooges to watch the door, Connie and the others quickly circle around Joyce. And now that they have this trapped rabbit’s full attention, Connie starts playing mind-games with the new girl, who does her best to keep up, be cool, and not offend the constantly contradicting Connie.

Told if she wants to survive and be popular in this school, Joyce had best join The Hellcats. But when the girl readily and somewhat fearfully agrees to do just that, the head Hellcat warns it won’t be that easy and she’ll have to pass a few tests first. And even then, she might not get in. However, Connie does lay off the stick and offers this carrot, saying she and the other girls will all be wearing slacks to school tomorrow. And if Joyce doesn’t want to feel left out, she should, too. When asked if that’s against the rules, Connie retorts, “I make the rules around here.”

Then, Connie takes up position behind the main desk and starts mocking the teacher until her lookout warns the principal is on the way. With that, everyone scrambles to their seat. And so, when the substitute and principal enter the classroom, they are greeted by a perfect picture of proper decorum.

Cut to the following morning, where we find ourselves in the Martin house and meet Joyce’s parents: Roger and Linda. A hard working lawyer, Roger (Shelton) grumps about Joyce’s tardiness to the breakfast table. Saying he barely recognizes his daughter anymore, he continues to complain about the amount of makeup his daughter slathers on and the necessity of those tight-fitting sweaters she always wears. And his constant mantra appears to be, "Kids today need more discipline."

Linda (Harris), meanwhile, does her best to act as a buffer between them. But honestly, she is so involved with her bridge club and social circle duties the mother seldom has a clue as to what her daughter is up to most of the time. And then Roger has another conniption fit with Joyce’s choice of wardrobe -- most notably the slacks -- when she finally joins them. Then, with one final harrumph, the old man drives her to school.

However, when Joyce waltzes into her Health and Physical Education class, the teen discovers she’s been had -- none of the other girls wore slacks, which are, indeed, against the school’s dress code. Luckily, Ms. Trudy Davis (Williams) is one of the few teachers Connie and The Hellcats don’t give any trouble to. Her classes are usually an open forum and today’s topic is Boys and the Mating Habits of the American Teenager.

But cool or not, Ms. Davis soon notices Joyce’s attire. Obviously having seen this kind of hazing before, the teacher asks if anyone had put her up to breaking the school’s dress code. And while Joyce doesn’t rat-out Connie, the girl is so upset and embarrassed over this fashion faux pas she bolts out of the classroom -- and right off the school grounds!

After finding her way into a coffee shop, the man behind the counter, Mike Landers (Halsey), see’s that the girl is upset about something and, hoping it would help, tries to get her to talk about it. And after a little more cajoling she spills the whole thing. Apparently, Mike is well aware of those hooligan Hellcats. But when he tries to warn Joyce to stay away from them a little too emphatically, the volatile girl angrily tells him to butt-out and tries to storm off.

But Mike, obviously smitten, apologizes and gets the girl to calm down. They share a cup of coffee and exchange stories on how they both wound up here. Mike is a few years older and is working his own way through college to be an electrical engineer. She thinks it must be great having all that freedom of choice, but Mike says don't be so sure since he has to pay for everything himself -- rent, tuition, books, food, which is why he is currently serving coffee and busing tables. When the palaver finally breaks up, Joyce promises to come back and see him again -- but not during school hours.

Arriving home to an empty house, Joyce's parents eventually do show up but then pay no attention to the obviously troubled teen. Later, she receives a phone call from Connie with an invite to a party. Later, when Joyce arrives at an abandoned movie theater as instructed, she's escorted up to the balcony -- The Hellcats home away from home.

Here, the newbie is informed that after not ratting them out to Ms. Davis, she's passed the first of three tests, making her a probationary member of the Hellcats. But even for probational members there are a few ground rules: first, you can’t be an egghead, a show-off, or a teacher’s pet; and second, one must never -- ever, reveal the location of their secret fort.

With that, Connie excuses the other Hellcats but asks Joyce and Dolly to remain behind. Once the others clear out, Dolly produces a bottle of whisky and pours out a stiff shot for Joyce, which she must drink to officially complete phase one of her initiation. And once the girl manages to choke that down, Connie declares she’s now ready for phase two, which means she'll have to steal something witnessed by another Hellcat. And while Joyce is a little trepidatious about this next step, I’d be more worried about the further escalation of phase three -- where somebody winds up dead…

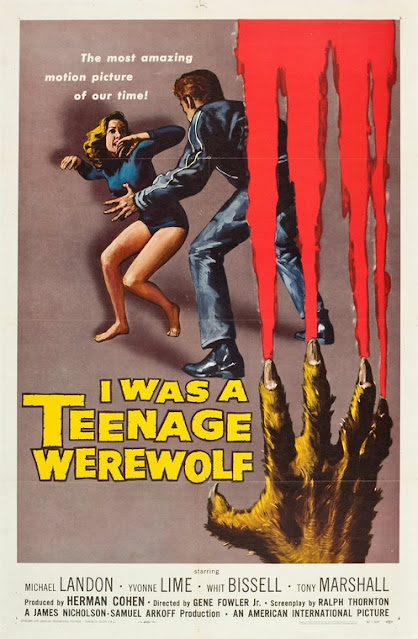

Prior to June of 1957, American International Pictures was still a small independent studio trying to find its legs. But that all changed with the release of I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), whose highly exploitable title, along with some tight direction by Gene Fowler, some beautiful and downright evocative cinematography by Joseph La Shelle -- 13 years removed from his Academy Award winning efforts in the film noir classic, Laura (1944), and an outre performance by Michael Landon really struck a chord with younger audiences and made AIP a fortune. (A $2-million return on a $100,000, six day wonder.)

It’s hero was a tortured soul unable to find his place in a world not built for him -- angsty, prone to violence, and unwilling to listen to those in authority. And why should he? As critic Robert Burstein wrote in his analysis Reflection on Horror Films (Partisan Review, 1958), “What these films seem to be saying, in their underground manner, is that the adolescent feels victimized by society -- turned into a monster by society.”

Here, Burstein recognizes how teenagers could relate “to this feeling of loneliness, fear, rejection and dramatic bodily change.” Thus, AIP had finally found their niche by making films about teenagers for teenagers without the usual moralizing or pandering.

This, of course, triggered a lot of pushback from the very same pillars of society they were constantly poking in the eye with their lewd and lascivious titles and promotional campaigns. In his autobiography (Flying Through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants, 1992), AIP co-founder Sam Arkoff included a letter written to him by Senator Paul Douglas (Illinois), who expressed his concerns thusly:

“The kind of picture you have made in I Was a Teenage Werewolf is of considerable concern to me. At a time when the country is sensitive to the problem of juvenile delinquency, we need the motion picture industry to take a responsible stand in the movies it makes for young audiences, rather than making movies that are scandalous and immoral.”

From the tenor of the letter, Arkoff quickly deduced that Douglas hadn’t actually seen the movie but based the entire complaint on just the advertisements, which he explained, in their zeal to get butts into the seats, were overdone on purpose. And after Arkoff offered to arrange a private screening of the film for the esteemed senator, he never heard from Douglas again.

Also, it was around this same time that Senator Estes Kefauver (Tennessee) started his crusade against the scourge of juvenile delinquency, who headed a congressional subcommittee to ferret out and squash the root causes of teenage degeneracy -- rock ‘n’ roll music, comic books, and the type of movies AIP was producing. Like with Douglas, Kefauver seemed more outraged by the posters and newspaper ads than the films themselves, saying they were “supercharged with sex,” and how “purplish prose is keyed to a feverish tempo to celebrate the naturalness of seduction, the condonability of adultery, and the spontaneity of adolescent relations.”

And while the committees’ findings found no real causation link between popular media and delinquency, it concluded that the “indiscriminate showing of scenes depicting violence or brutality constitutes a threat to the development of healthy young personalities.”

The Los Angeles Times, August 20, 1958.

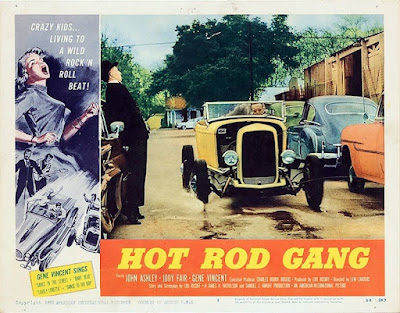

Thus, the witch-hunt was still on in 1958 with the release of the AIP double-bill, High School Hellcats (1958) and Hot Rod Gang (1958), whose breathless taglines screamed, “Proud young rebels! The true story of today’s youth!” See! “What must a good girl say to belong?” Hear! “The facts about taboo sororities that give them what they want!” Plus! “Crazy kids living to a wild Rock ‘n’ Roll beat!” And after taking all of that in, for his syndicated newspaper column, Hollywood Today (April 19, 1958), Erskine Johnson guaranteed this double-bill would ‘T’ off any PTA (Parent-Teachers Association). It sure did.

As a case in point, as reported in The Californian (September 23, 1958), in the first meeting of the season that year for the Salinas Valley council, “the organization went on record as disapproving the advertising of movies in the local papers, namely High School Hellcats and Hot Rod Gang.” And how a “Mrs. W. Laurence White reported on a conference sponsored by the 20th District PTA Welfare Department, whose featured speaker was Mr. George Saleebey of the Bureau of Probation and Delinquency Prevention Service.

The Lincoln Journal Star, August 29, 1958.

“Mrs. White reported that nowhere in California’s Welfare and Institution Code can you find the definition of a ‘delinquent.’ But Saleeby said that a delinquent is anyone committing an act that is against the law and is caught. He also said that delinquency is caused by a combination of things and no effective prevention has been found so far. The speaker stated that severe punishment is not the answer and publicizing names of juvenile offenders does not work. He added that only one per cent of the budget is now used for prevention.” Thus, it was up to the average citizen to take action.

And less than a month later, in that very same newspaper (August 11, 1958), an anonymous writer went apoplectic and wrote a scathing letter to the editor after encountering just the previews for this AIP double-feature while attending a much more wholesome revival screening of David O. Selznick’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1938), which were “so repulsive as to make [them] shudder.”

The concerned citizen then continued, saying, “In one, a high school girl, apparently innocent, is faced with the decision of whether or not to join the gang and “belong,” and decides to give it a whirl. A preview of the initiation shows her being given a shot of whiskey to drink, her shuddering and being told ‘You’ll learn to steal soon!’ There was a classroom scene when during the temporary absence of a teacher, these girls took over and bedlam broke loose in ridicule and shocking behavior. A rock ‘n’ roll hop turns into an “anything goes” party; and a gang of hot-rodders race their rods, two wheels in the street and two wheels on the curb, contestants on both sides of the boulevard.

“If I saw all of this in a few minutes of previews and it sickened me, what would two full-length pictures do to me? To our teenagers? And what benefit will there be in the ‘little grain of sand’ in the newspaper censoring newspaper advertising, when such entertainment as this is available for several hours at a stretch? Why in the name of everything that’s decent should such films be shown at all? And will I gain another grain of sand by writing in protest to Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, executive director of these two miserable pictures, while commending David O. Selznick for his excellent Tom Sawyer? Is it possible that this source of corruption can be eliminated in the very same way civic organizations, church organizations, PTAs and individuals, working separately and together with their little grains of sand, finally were effective in their war against disgraceful comic books?

“If you’re still reading, you are interested one way or another. If your not with me, get yourself a copy of the Discipline Referral Policy just circulated by the Salinas High School and read the 17 rules of conduct this school has found necessary to institute sometime in the interval between the 1920s when I went to the same school without any prior circulated rules and the 1950s, when these rules have become necessary!!! And then go see the schoolroom scene I described above!!! God grant you sleep that night if you are a teenage parent.”

And it wasn’t just ordinary citizens, teachers, community leaders, or parent groups that were protesting such impressionable “trash.” In October of 1958, as the legend goes, Arkoff and fellow AIP co-founder Jim Nicholson hosted a luncheon in Miami, Florida, for the gathered members of the Theater Owners Association of America to wine, dine, schmooze, and hopefully drum-up more exhibitors for their product. Also attending was producer Jerry Wald, who wrote and produced several classic film noirs -- They Drive by Night (1940), Dark Passage (1947) and Key Largo (1948), and who more recently produced some steamy, sinful melodramas for Columbia and 20th Century Fox -- Miss Sadie Thompson (1954), Peyton Place (1957), No Down Payment (1957) and The Long, Hot Summer (1958).

Both Arkoff and Nicholson were a little leery when Wald asked them to yield the floor because he had something important to say. And when they agreed, the producer went into a lengthy and somewhat hypocritical diatribe:

“Jim and Sam are nice guys,” said Wald. “But let's face it. AIP makes irresponsible movies. They aren’t the kinds of pictures you’d want your own kids to see. I’ve heard from some PTAs that have warned parents to keep their kids away from AIP movies like High School Hellcats and Hot Rod Gang. And I think I Was a Teenage Werewolf speaks for itself.” He then looked at Jim and Sam directly, saying, “I wish you would think about what you’re doing. These aren’t the types of pictures that are going to build a market for the future. You may make a few dollars from these movies today, but what about tomorrow? Please think about lifting your horizons!”

Now, what happened next is in semi-dispute as to who actually gave the rebuttal. According to the Arkoff bio, it was he who ripped into Wald when he was finished, saying, “Since we’re talking about movies let me remind you of [Wald’s] latest picture. Perhaps you’ve forgotten that Peyton Place is your most recent film. Now, when I saw Peyton Place there was one scene after another of rape, incest and murder. Rape, incest and murder! You’ve heard the cliche of people living in glass houses (and how they shouldn’t throw stones) haven’t you? Well, if you’re talking about films destroying the fabric of America, I think you should first look at your own!”

But in Fast and Furious: The Story of American International Pictures (1984), author Mark Thomas McGee credited this rebuttal to Nicholson, who added, “I’d rather take my own children to see one or our pictures than something, like, say, God’s Little Acre (1958)” -- based on a novel that was prosecuted for obscenity. “Our monsters don’t drink, smoke or lust. Can you say the same about the characters in your movies?” And none were ever condemned by the Legion of Decency, added McGee.

Now, it should be noted that High School Hellcats and Hot Rod Gang were not original AIP productions. Nope, they originated with, as the astute letter-writer already pointed out, Charles “Buddy” Rogers, who had split time as a singer and an actor -- with hits ranging from “I'd Like to Be a Bee in Your Boudoir” and “Moonshine over Kentucky” and who had starring roles in Wings (1927) and The Road to Reno (1931).

In June of 1937, Rogers married fellow actor and Hollywood legend, Mary Pickford. And while “America’s Sweetheart” was 11 years his senior, and the going consensus was that their marriage would never last, the two remained married until Pickford’s death in 1979. And while Pickford’s career in front of the camera waned after the switch to sound, Rogers successfully made the transition and continued acting well into the 1950s.

Charles "Buddy" Rogers and Mary Pickford (circa 1936).

Pickford, meanwhile, had been producing and financing features since The Foundling (1915), and would be a co-founder of United Artists (1919) and The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (1927). And in 1946, Pickford and Rogers would produce and finance Little Iodine (1946) and Susie Steps Out (1946) for UA.

Then, in 1958, Rogers and Ferde Grofe Jr. teamed-up and struck a two picture distribution deal with American International for High School Hellcats and Hot Rod Rock -- which eventually morphed into Hot Rod Gang. Grofe Jr. was the son of composer Ferde Grofe -- probably most famous for orchestrating George Gershwin's “Rhapsody in Blue” but also composed the scores for films like Rocketship X-M (1950) and The Return of Jesse James (1950). But the actual money would come from Pickford, who ponied-up $100,000 for each proposed feature. And one of the first expenditures of the newly formed Indio Productions was hiring Louis Kimzey as a creative consultant.

Lou and Irene Kimzey and their MG convertible.

A native Californian and well-immersed in the burgeoning hot-rod culture, Kimzey, at the age of 23, had served as the art director on Hop Up magazine, which first hit the stands in 1951. He would later become the founder and publisher of other periodicals all aimed at teenagers like DIG and Modern Times, as well as working for Motor Life and Road and Track magazines.

Kimzey would be credited as an associate producer on both High School Hellcats and Hot Rod Gang but most of his contributions were made on the second film. For not only did he help pitch in on AIP regular Lou Rusoff’s script, he also ran a publicity contest in DIG magazine, looking for people to enter photos of their hot-rods and souped-up jalopies for a chance to have them actually appear in a major motion picture.

This co-feature was directed by Lew Landers, who had been working behind the camera in the Bs since The Vanishing Shadow (1934). He would also direct the Karloff and Lugosi version of The Raven (1935), and Lugosi again in Return of the Vampire (1943). By the 1950s the director had latched onto Sam Katzman’s 4-Leaf Productions, subbing in for William Berke on a couple of their Jungle Jim features, starting with Jungle Manhunt (1951); but he also started transitioning into television.

Hot Rod Gang would be Landers’ second to last feature -- the last being Terrified (1963), a tale of a murderer running loose in a haunted house, and the atrophy was kinda showing. We did a quick review of Hot Rod Gang on the old bloggo; and while I think it’s still worth a spin to see Gene Vincent prowling around and doing his thing, everything else proved so ludicrously cornball that even I kinda lost patience with it as John Ashley has to wear a beatnik disguise to put on a show to raise the money to fix his car so he can win the big race to save his gang’s clubhouse from the wrecking ball. (And do NOT get me started on his two spinster aunts.)

But while Hot Rod Gang was essentially a musical and played for laughs -- which, along with Dragstrip Riot (1959) and Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow (1959), paved the way for AIP’s highly successful Beach Party (1963) franchise, High School Hellcats -- despite the hellacious title and lurid poster art courtesy of Al Kallis and Reynold Brown, would be a sobering and somewhat earnest attempt to spotlight and resolve what Kefauver and all of his blustering could not, as Joyce continues to be enticed down a road to possible ruination.

But what makes High School Hellcats so different is where it lays the blame for this behavior. For while it focuses on the symptoms of outside influences, the actual disease hits a little closer to home.

Thus, we continue to watch as Joyce takes yet another step down the wrong path when the girl accompanies Connie and Dolly to the local Five and Dime. And while the others run interference, a reluctant Joyce goes through with it and steals a pair of earrings. The trio then regroups later at Landers’ coffee shop, where Connie warns Joyce to stay away from the total square serving them. Thus, she gives Mike the cold shoulder while the other girls are around, but Joyce secretly arranges to meet him later on -- alone.

After they hook-up, the couple head for the beach, where Joyce apologizes for her rude behavior earlier and confesses to Mike about all her experiences so far with The Hellcats. She also reveals that, technically, she didn’t steal the earrings because she clandestinely left some money for them when the others weren’t looking. And here, when he’s unable to understand why she would ever want to join that group in the first place, Joyce echoes Connie’s earlier statement of a need for a “home away from home” and how “she has to belong to something.”

Not buying this, Mike counters, saying Joyce should consider herself lucky because she has good parents and the security that provides. He’s right, of course -- at least to a point, as Joyce doesn’t disagree but wishes her parents would show at least a little interest in what she’s doing and not just nitpick everything she does. Then the young lovers embrace, they kiss, the waves crash against the rocks, and I’ll let you all figure out what happens next from there as we fade to black.

The following day at school, Connie has finally come up with Joyce’s last test: she has to ask a boy named Rip out on a date while he’s talking to his girlfriend. Now, at this point, we also can’t help but notice that Dolly isn’t very happy with all the attention Connie’s been giving to the new girl. Her leader even quips if Joyce keeps it up, she might become her new favorite. (Nope. No lesbian subtext here. Move along, folks, nothing to see here...) Then, they both watch as Joyce passes the final test when Rip (Braddock) dumps his girlfriend on the spot for a chance to go out with a Hellcat on a Saturday night.

Of course, this probably explains why Mike and Joyce have a terrible fight on Saturday afternoon over the party she’s being forced to attend. (Wait. Forced?!) Ending badly, Mike angrily drives off while Joyce glumly retires to her bedroom to prepare for her other date.

Meanwhile, downstairs, her parents are at it again. Here, Linda thinks they need to get away for a private vacation but Roger refuses to let their daughter stay home alone by herself. Speaking of, before she can leave, her father gets in a few loaded shots on Joyce’s enticing makeup and dress. And then, after she’s gone, the parents bickering over their sole offspring resumes unabated.

Turns out Joyce and Rip are double-dating with Connie and her boyfriend, Freddie (Cook). And when they arrive at a rocking party, Rip immediately tries to get Joyce drunk so he can take advantage of her. But when she refuses to drink or dance, the boy just dumps her for an easier mark.

Then, as the party drags on indefinitely, Freddie proclaims it’s time to play a game of Sardines -- where the boy who draws the ace of spades out of the deck has to run around in the dark and identify as many people as they can. (And what the hell does any of that have to do with sardines? Well, let me get back to you on that.)

Once the player is chosen, the lights go out. But as Joyce fights off a phantom groper -- my money’s on that creep Rip, suddenly, a blood-curdling scream quickly drowns everything else out. And then, when the lights come back on, it reveals who did the screaming: Connie, who’s dead body is found lying at the bottom of a staircase!

Thinking she must’ve mistaken the stairwell for a closet while looking for a place to hide in the dark, Rip figures she must’ve accidentally fallen and broke her neck. Regardless, she’s still dead. And so, Rip swears everyone to secrecy before kicking them all out. He and Freddie then frantically start cleaning up the place. Turns out the real owners of the home were out of town and they were illegally squatting. The decision is also made to just leave the body where it landed and clear out.

When they drive a shell-shocked Joyce home, the boys find Mike there, waiting to apologize for their earlier fight. Thinking he’s a cop, a fight breaks out but the older Mike makes quick work of Rip and Freddie and sends them packing.

Here, Joyce convinces Mike not to call the cops as they head over to his place so she can clean him up and treat his scrapes and bruises. But visibly upset about something besides that fight, Joyce adamantly refuses to reveal what really happened at the party.

Cut

to Monday at school, where The Hellcats have another meeting. Here,

Dolly immediately takes charge. And convinced that it wasn’t an accident

and someone pushed Connie down the stairs, the hot-headed girl swears

if she ever finds out whodunit she’ll kill ‘em. Dolly then punctuates

this threat by turning a wrathful, accusing-eye on Joyce.

Later that day, Ms. Davis is called to the principal's office to meet with Lt. Manners (Anderson). There to investigate Connie’s disappearance, he asks the teacher to identify who the missing girl's friends were, and then to send them in, one at a time, for questioning. Eventually, it’s Joyce’s turn; but she doesn’t crack or confess anything. (Party? What party?) However, she does finger Dolly as Connie’s best friend (-- Wait. Connie? Connie who?), so Manners asks to see her next.

Now,

during this interview, Dolly slips-up by referring to Connie in the

past tense. Remember, the cops only thought the girl was missing. But

here, Dolly immediately clams up and refuses to cooperate any further.

Once all the interviews are completed, Manners can’t decide if the girls

are all telling the truth or if it’s all just one big organized lie.

He then consults with Ms. Davis again, since the girls seem to trust her. Saying the kids respect her because she respects them, the teacher promises to keep the detective in the loop if anyone confides anything about what happened to Connie or reveal her current whereabouts.

That evening, while on a date with Mike, a newsflash on the radio announces the discovery of Connie’s body. Mike feels this is good riddance to bad rubbish, but Joyce, obviously, is visibly shaken by the news. And while she still won’t reveal what’s been bothering her so much lately, the girl does promise to quit The Hellcats at the next club meeting.

Joyce then visits with Ms. Davis but can’t quite confess to her either. The next day at school, Dolly tries to sneak a note onto Joyce’s desk, saying there’s an ultra-secret Hellcat meeting tonight at the old theater. Here, Joyce catches her, announces she wants to resign on the spot, but Dolly won’t let her quit, saying there are a few things that need to be settled at the meeting first.

But after school, two other Hellcats -- Meg (Ames) and Laurie (Kilgas), approach Ms. Davis. Seems they found Dolly’s note about the secret meeting but no one else was told about it. And terrified because Dolly thinks Joyce killed Connie and wants some biblical revenge -- and she’s crazy enough to follow through on it, the girls then make a full confession about what happened at the party.

Thus, as Ms. Davis calls the police, Mike drives Joyce to the theater. And after reaffirming that she’ll only be attending long enough to announce her resignation, and will be back in less than ten minutes, Mike finally agrees to let her go in alone -- but warns he will not hesitate to come in after her once those ten minutes expire.

Inside, Joyce finds Dolly -- and her switchblade! Here, after chasing Joyce up into the balcony, Dolly confesses that she was the one who pushed Connie down the stairs in a jealous rage, convinced that Connie was trying to replace her with Joyce in the Hellcat hierarchy. Outside, when the police pull up and storm the theater, Mike follows them in.

Meanwhile, up in the balcony, as Dolly stabs at Joyce, she keeps managing to avoid the blade. But when her attacker wildly lunges at her dodging victim again, Dolly misses so badly she plunges over the balcony railing and smashes into the seats below, bringing our melodrama to a fatal conclusion. It's all over, and Mike and Joyce embrace.

Thus, as things wind down, Joyce confesses it was Dolly who killed Connie, and she tried to kill her, too. Here, Lt. Manners reminds her that she could’ve prevented all of this and saved a life by telling him this sooner. But he soon softens up and lets the traumatized girl go home with instructions to come into the station in the morning to make a full statement.

And so, while Mike drives her home, Ms. Davis telephones her parents and explains what just happened to Joyce. And only after an attempted murder does her parents begin to see the light as they welcome their daughter home with open ears and open arms and invite Mike to come inside with them. Let the healing begin.

Thus concludes another solid “troubled teen” effort that was shepherded into existence by American International Pictures. Nicholson and Arkoff would get top billing as producers and presenters, followed by Rogers as the executive producer, and then Kimzey as an associate producer. Apparently, Grofe Jr. got cold feet at the last minute and asked his name be removed from the credits, fearing the low rent production would besmirch the family name apparently.

High School Hellcats wouldn’t be AIP's first rodeo in the good girls gone bad subgenre, having already unleashed a triple whammy of Girls in Prison (1956), Runaway Daughters (1956), and Dragstrip Girl (1957) courtesy of Eddie L. Cahn and Russof, which were followed up by Roger Corman’s delightfully nutty Sorority Girl (1957) and Edward Bernds’ Reform School Girl (1957), who would also direct our featured feature.

Bernds broke into Hollywood as a sound engineer, where he would record and mix for the likes of Frank Capra at Columbia. There, Bernds would switch professions and start writing and directing short subjects, starting with the Three Stooges’ A Bird in the Head (1946), which featured an ailing Curly Howard after he had suffered through a series of debilitating strokes.

“It was an awfully tough deal for a novice director to have a Curly who wasn't himself,” said Bernds (The Three Stooges: An Illustrated History, From Amalgamated Morons to American Icons, 1999). I had seen Curly at his greatest and his work in this film was far from great. As a fledgling director, my plans were based on doing everything in one nice, neat shot. But when I saw the scenes were not playing, I had to improvise and use other angles to make it play.”

Going clockwise from left: Larry, Edward Bernds, Shemp, Moe.

Bernds would then continue writing and directing Stooges shorts and expanded into features, taking over the Penny Singleton and Arthur Lake Blondie adaptations with Blondie’s Secret (1948) through Beware of Blondie (1950). But when Columbia downsized in 1952, Bernds left the company.

But he landed on his feet at Monogram, where he took over the production of The Bowery Boys franchise -- starting with Private Eyes (1953), which would eventually earn him an Academy Award nomination in 1956 -- well, sort of. See, the Academy actually meant to nominate John Patrick for writing High Society (1956), a Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby musical for MGM, and not Bernds and his longtime partner Elwood Ullman, who co-wrote the script for another High Society (1955) -- a Huntz Hall and Leo Gorcey Bowery Boys feature directed by William “One Shot” Beaudine. Realizing this mistake, Bernds and Ullman graciously withdrew their nomination -- though it's still noted in the Academy records, and Bernds kept the official notice framed on his office wall.

That same year, as Monogram continued to transition from Poverty Row and turn into Allied Artists, Bernds would direct the ambitious sci-fi epic, World Without End (1956), where four far flung astronauts wind up right back where they started, and later the not so ambitious but totally loony interstellar battle of the sexes, Queen of Outer Space (1958).

After that, the director would freelance, bouncing around between Allied Artist, AIP, and Robert Lippert’s Regal Pictures, where he teamed up with Bernard Glasser on the criminally underrated gem, Space Master X-7 (1958), where a space-probe returns from Mars carrying a deadly fungus that’s being unwittingly spread around the country by a female fugitive, leading to a rousing manhunt before the whole country gets infected and overrun by colonies of the dreaded “Blood Rust.” And oddly enough, Moe Howard was there, too.

Bernds would also do Return of the Fly (1959) for Regal, and then returned to Columbia for Valley of the Dragons (1961), along with the giant spider-prop he’d used in World Without End and Queen of Outer Space. (The veteran director and writer wasn’t one to give up on a successful gag.) Bernds would also reunite with Moe, Larry and Curly Joe DeRita and helped introduce them to a whole new generation of fans with The Three Stooges in Orbit (1963).

In between all of that Bernds tackled High School Hellcats for Rogers and AIP. Here, he turned in another rock-solid effort. No frills. No bells. No whistles. Just a workmanlike end result that definitely plays, and even enlightens if you keep your eyes and ears open.

His cinematographer on the picture was Gilbert Warrenton, another seasoned veteran, who started in the silents with The Hard Rock Breed (1918), who managed to extend his career into the 1950s by attaching onto independents like Ron Ormond and Mesa of Lost Women (1953) -- before Ormond survived a plane crash, abandoned exploitation pictures, and started making religious films for Estus Pirkle that are zealously and utterly bonkers -- If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? (1971), The Burning Hell (1974).

And Warrenton did a ton of pictures for AIP, too -- Submarine Seahawk (1958), Paratroop Command (1958), and up through Panic in the Year Zero! (1962) and Operation Bikini (1963). And while he didn’t possess as keen an eye as, say, Floyd Crosby, his efforts do have a few flashes of brilliance. I really love how he shot the climax in the darkened theater, with only Dolly’s flashlight providing the illumination.

And while I poked fun at its over-saturation, Ronald Stein’s main theme from High School Hellcats slaps hard. Sorry, Blackboard Jungle (1955), forget about it, Bill Haley, and suck it, “Rock Around the Clock.” I swear, if the roadway to teenage hell isn’t paved with this theme, I would like all of my juvenile sins back, please and thank you.

Now, I mentioned the promotional art earlier. And as the old joke goes, theater chain owners made no secret about openly wishing they could just poke sprocket holes into AIP’s posters and run them instead of the actual feature because those posters usually promised something the films rarely delivered on -- and often proved far more entertaining than the film itself. And, yes, the bosom-busting romance novel artwork for High School Hellcats is a tad over-heated and misleading, but there is a lot more going on than the titillating title lets on. Sure, you could easily write this off as just another low-budget exploitation quickie, but I think that’s selling Mark and Jan Lowell’s script way too short. And it was their efforts, I think, that really sets this film apart.

Shamokin News Dispatch, November 1, 1958.

Mark Lowell and Jan Englund were both actors, who formed a screenwriting team after they got married -- usually credited together as J.R. Lowell. And together they wrote the screenplays for High School Hellcats, Diary of a High School Bride (1959), and His and Hers (1961). They would later move to Italy, where Mark would pitch in on the English dialogue for A Fistful of Dollars (1964), which officially kicked off the Spaghetti Western craze.

Here, they threw everything in the plot pot -- peer pressure, hazing, felonies, the pursuit of the opposite sex, and under age drinking -- but no illicit drugs; nope, AIP wouldn’t tackle that until Cool and the Crazy (1958). Again, these are just the symptoms.

Joyce’s spotlight confessions and the confrontations between her and her parents are the best written scenes. These are good people and provide her with every material need, but are completely ineffectual if their daughter needs help or support emotionally. Her father rides her constantly about the way she dresses -- and even slaps her once when she gets a little too mouthy. Horrified by what he’s done, Mr. Martin still doesn’t have an answer when he asks, "Why did I do that?"

There’s also a skeevy incestual element at play, too, as Roger Martin can’t seem to come to grips with his little girl blossoming into a -- well, a fully endowed woman. For him, this simply does not compute. And in a weird way. Is this why he so staunchly refuses to let her date -- even a nice guy like Mike? (Yet another secret poor Joyce must keep bottled up, and more feelings she must repress.) Is this why he freaks out over her too-tight sweaters and the amount of makeup she always wears? And! His massive meltdown that led to the slap heard ‘round the block was triggered by Joyce running around the house in a slip and nothing else. Yikes. Too old for this, too young for that. What’s a teenager to do?

And later, when she really needs a lifeline and tries to talk to him about Mike, the Hellcats, the deadly party, everything, dear old dad basically hides behind his newspaper until she gives up and moves on. He simply has no idea how to talk to her while she’s in this developmental no-man’s-land. A truly disheartening moment, that the Lowells, Bernds and Warrenton pull off brilliantly, giving the extra effort needed to land the scene and make it stick.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Martin is a bit of a conundrum. Linda Martin does her best to act as a buffer between her husband and her daughter. Clearly, she is on Joyce’s side in these constant tête-à-têtes and feels her husband is overreacting. And yet she’s too busy with her social activities and can’t fit Joyce anywhere into her schedule. There’s a scene where Ms. Davis tries to arrange a meeting with her over the phone to discuss Joyce’s problems. She tries for three consecutive Saturday’s with no luck.

And most damning of all, we have the scene where Linda suggests they should take a vacation, alone, and her hubby asks if she's forgetting about Joyce, I’m not sure what’s more disturbing -- the fact that she did forget about her daughter, or the fact she seemed kinda disappointed that her only child just ruined their vacation plans.I suppose one could read this scene as Linda trying to get Roger to loosen the leash a bit, but, still.

Then, all of this dissonance comes into a sharp focus when Joyce talks to an incredulous Mike about why she wants to join The Hellcats. It’s because this gives her a feeling of belonging. Stability. Someone who will not only listen to her problems but understand them. Like the other Hellcats, Joyce is a latchkey kid. Her parents haven’t the time, patience, nor the inclination to pay attention to her while the Hellcats do. Which leads us back to Connie’s "home away from home" speech -- that should be interpreted literally as a physical safe home away from her real home.

The film then takes this one step further by siding with the younger generation -- much to the delight of its target audience, no doubt. When her father grounds her, Joyce bites back, saying children have rights, too, as well as responsibilities.

Thus, while everyone else was laying the blame for this kind of delinquent behavior on outside influences, the real problem according to this cheap little exploitation movie lies with the dysfunctional family and a failure to adapt at parenting, as each new generation of kids faces a whole new slew of problems the previous couldn’t even dream of dealing with. (And it’s only gotten worse as we’ve gone from rock ‘n’ roll necking parties to mass shootings.) This film is begging parents, pundits, PTA groups, and muckraking Senators, to realize that adults are part of the problem, to pay attention, and to just listen to their kids.

Helping sell all of this are a trio of standout performances. Yvonne Lime had co-starred in I Was a Teenage Werewolf as Michael Landon’s girlfriend. She has a natural, wholesome perkiness and a 10,000-Watt smile that’s kind of endearing. Lime also filled out those sweaters and vintage fashions quite admirably. Wowsers.

But what I really liked about her performance is Joyce’s inner struggle, her vulnerability, and the constant ‘deer caught in the headlights’ reaction when dealing with the overwhelming Connie. And I love it whenever she shows a little backbone when dealing with her parents or her boyfriend.

Jana Lund is also a lot of fun as the conniving Connie Harris. That same year she had starred in the Elvis Presley vehicle, Loving You (1957), who tried to vamp her way into an already crowded love triangle between Presley, Dolores Hart and Lizabeth Scott. (Come to think of it, Lime was one of several starlets Presley hooked-up with for a hot minute before he got drafted.)

But if I’m being honest, Susanne Sidney kinda steals the movie as the bitter and psychotic bulldog, Dolly Crane -- her total credit list is way too short, IMHO. The scenes where she melts down on Lt. Manners, or the climax when she snaps for good and goes after Joyce are a total gas. And make no mistake, it’s these girls that make this movie tick.

“No doubt the punk kids in the audience for High School Hellcats sneered their appreciation for this movie, while the ‘good’ kids sat there and secretly thrilled to something they wouldn't have had the nerve to do themselves,” said Paul Mavis (DVD Talk, May 16, 2011). “Indeed, High School Hellcats is quite good at setting up a framework of wish-fulfillment that must have found particular favor with the young women in the stalls; after all, the film is almost entirely geared towards satisfying them: the female viewer (-- an early deviation in the AIP formula, where young male viewers were usually the target demographic).”

And, “Given the choice of two characters in which to identify with -- impossibly good, sweet, pretty-yet-conflicted Joyce, or hard, sexual, criminal Connie -- girls sitting and watching in the darkened balconies could’ve been excused from warding off their boyfriends' straying hands as they alternated from positive idealization of Joyce to naughty, pleasurable fantasizing about confident Connie (-- they probably cheered, too, at Miss Davis' assertion that it was nonsense to believe women were somehow genetically inclined to be monogamous).”

Mavis also picked apart Joyce’s relationship with Mike Landers -- played by Brett Halsey, currently on a layover at AIP after getting dumped by Universal International before heading off to Italy to try his fortunes there. As the voice of reason, “he made all the right noises about being alone in the world while looking for love.” But when he gets a little too controlling and judgemental -- just like her father, Joyce blows up at him, too, and they break up; at least temporarily.

That might be a little rough on Mike -- he’s a pretty stand-up guy, and I actually kinda liked their first meet-cute, but I am clearly in the minority. Said Jim McLennan (Girls with Guns, August 24, 2016), “It’s notable that, unlike some entries in the ‘teenage girl gang’ genre, the Hellcats are not an off-shoot of a male gang, or indeed, beholden to men in any way -- the only male character of note is Mike, and he is basically as useful as a chocolate teapot. Even at the end, when Joyce is lured into a late-night meeting at the derelict cinema, which is the gang’s HQ, he serves no significant purpose. That’s remarkably advanced for its time, and is the kind of forward thinking which keeps this film watchable when, let’s be honest, many of the topical elements are way more likely to trigger derisive snorts in the contemporary viewer.”

Look. He’s not wrong. Not all of it works. The majority of the high school cast look like they all got held back for at least eight consecutive years, maybe longer in some cases -- looking at you, Rip. Some scenes clunk and wheeze, but when it does work High School Hellcats is really and truly something -- and it deserves to be heralded above its like-minded brethren of this strata. And the truly depressing thing is, no one was paying attention back in ‘58 as we’re still arguing over the exact same cause and effect some 65 years later -- and counting.

Originally posted on September 29, 2000, at 3B Theater.

High School Hellcats (1958) Indio Productions :: American International Pictures / EP: Charles "Buddy" Rogers / P: James H. Nicholson, Samuel Z. Arkoff / AP: Lou Kimzey / D: Edward Bernds / W: Jan Lowell, Mark Lowell / C: Gilbert Warrenton / E: Edward Sampson / M: Ronald Stein / S: Yvonne Lime, Brett Halsey, Jana Lund, Susanne Sidney, Rhoda Williams, Don Shelton, Viola Harris, Robert Anderson, Martin Braddock, Tommy Cook, Heather Ames, Nancy Kilgas

%201958.jpg)

%201958.jpg)

%201958_HSHC-06.jpg)

%201958.jpg)

_23.jpg)

%201958.jpg)

%201958_HSHC-07.jpg)

%201958_HSHC-15.jpg)

%201958.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment