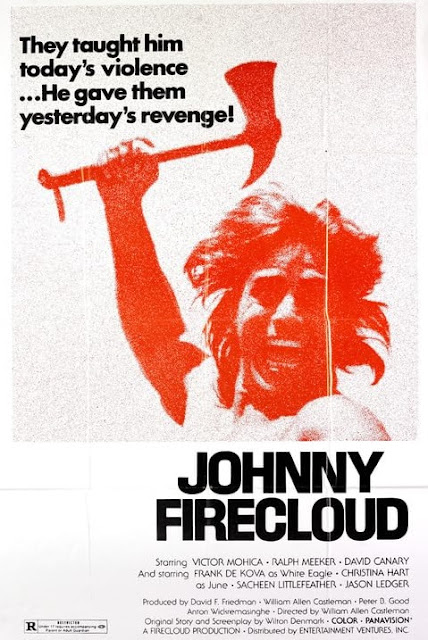

Our latest feature wastes little time getting up to speed, as we've barely passed the opening credits before our professed hero is being hassled by the authorities.

Here, a wary Johnny Firecloud is pulled over for a spot-check and asked to step out of his truck by the County Sheriff. But finding no violations with the vehicle, Sheriff Jesse soon makes one by kicking out a taillight.

Knowing the real reason behind this constant harassment, and about to fill us in, Firecloud (Mohica) mocks Jesse (Canary), saying he has “the balls of a mouse” and is nothing more than a paid stooge for Old Man Colby -- a local fat-cat rancher, whose influence is like a malignant tumor on the community, and whose pathological hatred for Firecloud knows no bounds.

Seems that before he got drafted and went off to fight in Vietnam, Firecloud and Colby's daughter, June, were lovers. But being the ingrained bigot and all around no-goodnik that he was, unbeknownst to the couple, Colby intercepted and destroyed all communications between the two after Firecloud shipped out. And after several letters went unanswered, both brokenhearted parties assumed the relationship was over.

Unaware of her father's treachery, June (Hart) has been wallowing around the bottom of a liquor bottle ever since; and after Firecloud's hitch was up, he returned home and quickly found out that Colby (Meeker) was still holding a massive grudge and was determined to make the returning veteran's life miserable on every front imaginable, including getting him fired from his latest job as a hired hand at a neighboring ranch.

Now, the only reason Firecloud even sticks around at all is to be near his grandfather, White Eagle (DeKova), the chief of the local reservation, who raised his grandson after his parents were killed. But Johnny seems embarrassed by the old man, and constantly refuses to acknowledge his heritage, wanting to forget the past and live in the present. It doesn't help matters that his grandfather spends most of his time in the local bar, perpetually snockered, and will do almost anything to get himself another drink.

Unfortunately for him, Colby's goon-squad is full of suggestions and take sadistic pleasure in embarrassing the elder, smearing his face with lipstick for war-paint and making him dance for another shot of whiskey. And when Firecloud tries to stop this and take White Eagle home, Colby gives the signal and the goons quickly turn on him instead.

Outnumbered, Firecloud takes a beating; and while they wait for him to dance in his father's stead, they fail to realize that all their victim was doing was using this respite to get his second wind...

One of the many, many cultural sins the United States of America still hasn’t come to grips with yet, let alone make amends for, is the abysmal treatment of Native Americans. Even the use of the word “Indian” is derogatory, coined by Christopher Columbus when he didn’t discover America back in 1492; and who was so technically lost, the man thought he’d reached the East Indies.

And nothing epitomized this repugnancy more than the mantra of Captain Richard H. Pratt. Pratt was a Civil War veteran, who was adamantly against the idea of segregation and the use of reservations and favored assimilation, calling for all tribes to renounce their heritage, convert to Christianity, and become proper U.S. citizens. Which led to his declaration that the government must first “kill the Indian, to save the man.”

Image courtesy of the Museum of Western Colorado.

This attitude was compounded further by General Philip Sheridan, another Civil War vet, who did to Virginia what Sherman did to Georgia. After the war, Sheridan joined the effort to quash native hostilities out west. In January, 1869, Sheridan held a conference with 50 native leaders at Fort Cobb, located in what was then the Oklahoma Territories.

There, as the legend goes, a Comanche chief named Toch-a-way told his host that he was a “good Indian.” To which Sheridan replied, "The only good Indians I ever saw were dead." And over time, this answer eventually morphed into the oft-quoted, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian."

Artist rendering of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre (Robert Lindeaux).

Meanwhile, noted journalist, satirist, and cultural critic curmudgeon H.L. Mencken once noted: "Nobody ever went broke underestimating the taste of the American public." This is a bit of a falsehood in that the quote has no traceable attribution, as it appears in none of Mencken’s published work, which doesn’t mean he never did say it. It just means he never wrote it down.

As for the truth of its sentiments for whomever coined it, well, the proof, as they say, is in the pudding; for we are a weird and perverted lot when it comes to our popular entertainment despite (or in spite of) the puritanical rhubarb that usually accompanies it.

David F. Friedman.

Like a lot of infamous exploitation film pioneers, producer David Frank Friedman learned the fundamental tools of the filmmaking trade while serving in the Army Signal Corps. He’d been infatuated with show business since he was a kid growing up in Alabama, touring carnivals and sideshows or going to the movies, where his mother often played the organ to accompany the silent films.

With the outbreak of World War II, Friedman was drafted and served in Europe with the Signal Corps. When he was discharged in 1945, the ex-serviceman found himself settling in Chicago, where he became a press agent for a traveling carnival and eventually bought out the owner. He then went to work for Paramount as a regional publicity man in Atlanta, Georgia, with future stops in Charlotte, North Carolina, New York City, and then wound up back in Chicago; and by that time it was already clear Friedman had a gift for ballyhoo and showmanship.

The Des Moines Register (June 26, 1953).

As a case in point, when the Tony Curtis vehicle Houdini (1953) hit Des Moines, Iowa, Friedman offered $100 to anyone who could successfully escape from a straitjacket like the great escape artist featured in the picture. Unknown to the locals, the stunt was rigged, the fix was in, and the con was on as Friedman had hired a local teenager to be his challenger / ringer, who easily escaped the rigged restraints, garnering a ton of free publicity that $100 wouldn’t even begin to drum up through normal channels.

But around 1956, Friedman started moonlighting for Irwin Joseph and his Chicago-based Essanjay Films, which produced low-budget stag-loops and graphic sex-hygiene films. Joseph had made some hay with a re-release of an old Czech film called Extase (1933). Purported to be the first film to portray sexual intercourse and a female orgasm (mostly implied), Joseph repackaged the film in 1953 as Ecstasy. Why all the hubbub over some moldy but artful oldie? Well, turns out the actress having that orgasm was Heddy Lamar (-- billed then as Heddy Kiesler).

And not long after, Friedman would quit Paramount and become a full-time independent producer of low-grade smut. “Their cinematic efforts were cheaply made, often crudely produced, and had thin or nonexistent plots,” noted Frederick Burger (The Los Angeles Times, February 24, 2002). “But their movies were guaranteed to entice eager customers into dark movie houses with the promise of seeing the unbelievable and forbidden.”

But, as Burger pointed out in that same article, “Those films never actually delivered. They were all con-jobs that played on the audience's prurient expectations.”

“I never did consider myself a pornographer,” Friedman admitted to Burger. A huckster, yes. A pornographer, no.

“His horror and ‘sexploitation’ movies were hardly pornographic, at least by today’s standards,” said Burger. “But they enticed audiences with material that teased and titillated and seemed to offer glimpses of the taboo.”

“The secret of my stuff was the old carnival tease,” explained Friedman. “The audience would think: ‘Oh, boy, we didn’t see it this week, but next week!’ They never did see it, but they kept coming back.”

Added Friedman (ibid), “We were fortunate that we were in the independent-film business, running between the raindrops. I’ve always said I made some terrible pictures, but I don’t make any apologies for anything I’ve ever done. Nobody ever asked for their money back. [And] fortunately, the great American public, in their wisdom, took these pictures to their hearts.”

Kroger Babb.

At some point, Friedman and Joseph also went into business with Kroger Babb and Modern Film Distributors. Now Babb was the ultimate Cinema Huckster of his generation, and Friedman would be his dutiful apprentice. It was Babb who truly revolutionized the art of the Road Show with Mom and Dad (1945), another sex-hygiene film that featured the live-birth of a baby on film. But the featured forbidden feature was only a small part of the production.

As Friedman explained to John McCarthy (The Sleaze Merchants, 1995), “If you want to see a movie, you can watch one on television. Babb gave you a show. Of course, you saw half the show before you ever even got into the theater. That’s exploitation.”

Coupled with a lecture by the "Fearless Hygiene Commentator Elliot Forbes,” and pamphlets and How-To guides sold in the lobby, it was a three-ring, P.T. Barnum-type atmosphere brought into the hard tops and drive-ins all over the country. Using blitzkrieg tactics, advance agents went in first to inundate the venues with propaganda and ballyhoo. Then ringers were sent in to stir-up controversy; and in some instances, Babb even swore out injunctions to stop his own show to ramp-up the publicity even more.

Thus, it’s hard to judge Road Show features like Mom and Dad or She Shoulda Said No (alias Wild Weed, alias The Devil's Weed, alias Marijuana, the Devil's Weed,1949) today because, as Friedman said, we’re only getting half the show. We missed out on the build-up, the ballyhoo, and the bullshit.

The best modern equivalent for a Road Show experience would probably be The Blair Witch Project (1999). If you missed out on the viral marketing aspects of it, spending sleepless nights leading up to its theatrical release navigating their dial-up website, exploring the slowly expanding lore, you didn’t get the whole scope of it nor the whole impact. And once that spell was broken, there’s no getting it back. The moment had passed.

Thus, it was Babb who taught Friedman that it was all about the tease. To sell the “sizzle” and not the steak to keep the rubes coming back for more; for the sizzling tease was all about getting more butts into the seats and more money in your pocket. And when Babb decided to call it quits after touring an Italian version of Uncle Tom's Cabin (alias La capanna dello zio Tom, 1965), which had the production design of Gone with the Wind but a soundtrack where everyone sounded like Chico Marx, Friedman bought him out, too.

The Grand Island Independent (April 19, 1969).

“God knows X-rated or adult / exploitation films have been around as long as there have been movies,” Friedman explained to Jim Morton (Research #10: Incredibly Strange Films, 1986). “After getting out of the army I was with Paramount, then I decided I’d better get into something for myself. So I went into independent film distribution, which soon came to mean skin-dependent film distribution, because the only pictures which were available to independents were foreign films and cheap little pictures that flashed a tit -- something you couldn’t even do in those days.”

Friedman then further explained to Morton how the venues that became porno houses were originally art-house theaters. Said Friedman, “We used to call them ‘coffeehouses’ because all the intellectuals and pseudo-intellectuals would go in to see foreign films with subtitles and would sip coffee and talk about how Buñuel is doing this and that -- all of that bullshit.”

Then, “Around 1955, And God Created a Woman (alias Et Dieu... créa la femme, 1956) came along, starring Brigitte Bardot. Suddenly, these nice little coffeehouses that showed these pictures with subtitles had lines around the corner. The theater manager would say, ‘My god, what happened? Where did all these people come from?’ Well, they’d all come to see Miss Bardot’s bare ass.”

Roger Vadim’s And God Created a Woman was then followed by another French film, Louis Malle’s The Lovers (alias Les amants, 1958), and Friedman started noticing a pattern.

“A few distributors found out that the French weren’t the only ones (pushing sexual boundaries); the Swedes were making films with a little skin, too,” said Friedman (ibid). “That’s where One Summer of Happiness (alias Hon dansade en sommar, 1951) and The Naked Night (alias Gycklarnas afton, alias Sawdust and Tinsel, 1953) came in. Nobody was buying Ingmar Bergman for his creativity or because he was a great film director; they were buying it because he showed some ass and tits!”

Thus, these types of foreign skin-flicks kicked in the door to legitimize nudity in the movies and would inevitably influence domestic output, too, in order to compete as this type of picture started going mainstream, starting with Russ Meyer’s The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959). As Friedman said, “I’ve always felt Immoral Mr. Teas was nothing more than a cheap American version of Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (alias Les Vacances de M. Hulot, 1953).” Meyer wouldn’t deny Jacques Tati’s influence on his film, which was promoted as “A French Comedy for Unashamed Adults” and “A Ribald Film Classic” shot “In Revealing Eastman Color.”

And lo, The Nudie-Cutie was born. Said cult filmmaker Frank Hennonlotter -- Basket Case (1982), Frankenhooker (1990) -- "In an era when almost anything sexual could be considered obscene, it was the logical outgrowth of both the Burlesque film and the Nudist Camp movies of the 1950s. The result was a sex film without any sex. They were called Nudie-Cuties, and they were undoubtedly the stupidest films on the face of the earth." (Something Weird Video, 2001.)

Friedman felt the same way about the first wave of Nudie-Cuties, including Meyer’s follow-ups, Eve and the Handyman (1961) and Wild Gals of the Naked West (1962); and others like Francis Ford Coppola’s ignominious debut films Tonight for Sure (1962) and The Bellboy and the Playgirls (1962); and Doris Wishman’s Nude on the Moon (1961), thinking even he could make something better than that. Enter Herschell Gordon Lewis.

Lewis had already produced two features for Fred Nile’s Mid-Continent Films. First was The Prime Time (1960), a wild and raunchy tale of juvenile delinquency, beatniks, cat-fights, skinny-dipping, and Rock ‘n’ Roll, which was shot in Chicago.

“I can best describe it as a nothing picture,” a self-deprecating Lewis recalled to Andrea Juno (Research #10: Incredibly Strange Films, 1986). “It was about a young girl who is wild, looking for thrills and kicks. There was nothing in it that had any box-office appeal.”

The second feature was also Lewis’ directorial debut, Living Venus (1961), which was loosely inspired by Hugh Hefner’s efforts to get Playboy Magazine off the ground. “It was a more playable picture,” Lewis admitted to McCarty (The Sleaze Merchants, 1995). The mini-auteur would also give McCarty a crackerjack clinical definition of what an exploitation feature is:

“An exploitation film is a motion picture in which the elements of plot and acting become subordinate to elements that can be promoted -- elements the promoter can grab on to and shake in the face of theater owners to get them to play the picture and in the face of the public to get them to go and see it.”

Herschell Gordon Lewis.

Lewis and Mid-Continent Films would turn to Joseph, Friedman and Essanjay to distribute The Prime Time. Joseph would help finance the picture, earning himself an associate producer credit. Friedman, meanwhile, was tagged as a production supervisor, who I would guess was responsible for adding in some exploitable elements to the picture -- namely, the clumsy inserts of women taking their clothes off for the camera on top of the nudity already present to punch things up even more.

Turns out one of those models who bared all was played by Karen Black -- Five Easy Pieces (1970), Nashville (1975), whose agent later paid Friedman $2500 to have those scenes excised and the footage burned before its release, which nearly put the film into profit before it even hit theaters.

The Patriot News (March 16, 1960).

But honestly, it really wouldn’t have mattered as The Prime Time fizzled and disappeared rather quickly from the few venues it played, usually paired up with Kurt Neumann’s Carnival Story (1954), despite some amazing print ads. Living Venus fared better, but not enough to save Essanjay from bankruptcy, with Mid-Continent folding not long after.

Despite the financial setback, something had clicked on a fundamental level between Friedman and Lewis. “Herschell is probably the single smartest individual I ever knew in my life,” said Friedman (Morton / Juno, 1986). “He could write faster, quicker and better than anyone I’ve ever known. If he sees somebody doing something, whether it’s making an automobile or performing brain surgery, he can do it; he’s unbelievable. We did everything together. We did the campaigns together; we distributed together; we could anticipate each other; it was the greatest team since Barnum and Bailey.”

This feeling was mutual. “I felt that Dave Friedman was a master of campaigns,” said Lewis (Morton / Juno, 1986) “He and I literally taught each other the business, because I had no fear of the technical aspect of filmmaking. Nothing puzzles me; if a camera quit running, I’d take it apart and make it run. Nothing bothered me in the shooting of films. In the campaign of films, although my background was in advertising, it hadn’t been the kind of hard-boiled, rock-em-sock-em slam-bang advertising as Dave’s had. So Dave taught me campaigning, I taught him how to technically make a film, and the marriage worked out very well.”

Right before Essanjay folded, Friedman met up with an old acquaintance, Rose La Rose, an old-school stripper, who currently ran a burlesque house in Toledo, Ohio, who supplemented her shows with one reel nudies and stripteasers.

The Ledger Star (November 21, 1953).

These shorts were provided by Dan Sonney, who was the son of legendary film exploitation pioneer, Louis Sonney -- Maniac (1934), Hell-A-Vision (1936), The Wages of Sin (1938), who, along with the likes of Babb and Dwain Esper, operated “outside the framework of the motion picture industries Hayes Code,” and “were named by law enforcement officials and motion picture exhibitors alike as 'The 40 Thieves.’”

“These pantomime shorts were not stag films, by any means,” said Christopher Wayne Curry (A Taste of Blood: The Films of Herschell Gordon Lewis, 1999). “They were simply excuses to show women in various stages of undress. The point of all this is that LaRose’s customers loved these shorts, they did not have to wade through plot or character development. They were simply shown skin, and lots of it. And the only flaw in Dan Sonney’s scheme was that he chose to shoot them in black and white.”

Now, Friedman had hoped to get La Rose to screen Living Venus but she wasn’t interested in a full length feature; but she was interested in funding more one-reelers, especially if they could be upgraded to color. To pull these off, he brought in Lewis, and, “We kicked it around and ended up writing four or five little sequences,” said Friedman. And then he said, “Why don’t we just put ‘em all together?”

This they did, and the end result was The Adventures of Lucky Pierre (1959), whose script was knocked out in just six hours and then shot in only three days with a crew of three. Said Friedman,“On that one Herschell was doing the camera, I was doing the sound, and there was just one kid to help us pick up. That was the whole crew.”

The El Paso Times (March 6, 1964).

Upon its release, with the patented Friedman ballyhoo dripping off the ad mats and press kits -- “Pierre the Girl Examiner, See Him Bare Hidden Assets!!! Delightful, Delectable, Desirable, Delicious Damsels Devoid of Any and All Inhibitions! Ad Hoc Advocated Adult Amusement Filmed in Fleshtone Color and Skinamascope” -- The Adventures of Lucky Pierre was a bona fide hit, raking in some $200,000.

Somewhat serendipitously, around the same time, the New York State Court of Appeals came to a landmark decision in the Excelsior Pictures vs. New York Board of Regents case, which concerned Max Nosseck’s shot-in Florida film, Garden of Eden (1954). For it was with this film, where a stranded motorist finds safe refuge at a nudist camp, after a long and lengthy court battle, it was decided that: "Nudity, on its own, had no erotic content, and therefore was not obscene."

(Apparently, Blogger never got the memo.)

And with these loosening of moral standards, “Everybody ran into New York City with a nudist colony picture,” said Friedman (McCarty, 1995), to cash-in. “Herschell and I immediately went down to Florida and started grinding out nudist colony films. The first one we made for ourselves was Daughter of the Sun (1962). That girl (Rusty Allen) was so gorgeous it wasn’t even funny. Then Tom Dowd, who was an exhibitor in Chicago, wanted to make some. So we made Nature’s Playmates (1962), Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963) -- we ground those things out like sausages. Then we made one for Leroy Griffith called Bell, Bare and Beautiful (1963) starring Virginia Bell.”

“So we made a bunch of harmless, we used to call them Nudies,” said Lewis (Morton / Juno, 1986). “But again, in today’s marketplace they weren’t Nudies at all because nothing was bared below the top half, and they were completely innocuous; although in context of the times there was a certain amount of daring to them.”

And while all were successful financially, audiences were already growing fickle, even the raincoat crowd, and grosses were starting to wane. Said Lewis (McCarty, 1995), “After a time I became increasingly disenchanted with [the Nudies]. After all, there were only so many ways to show girls in a nature camp playing volleyball. I told Dave I didn’t want to make any more Nudies. I felt that our picture BOIN-NG! (1963) was the best one yet made and that we weren’t going to beat it.”

Friedman concurred, “We started getting tired of them and started kicking around other exploitable ideas.” One of the offshoots of the Nudie was the Roughie, which started to mix the tantalizing sex with some titillating violence and sadism, epitomized by Georgie Weiss’ totally bonkers Mistress Olga oeuvre: White Slaves of Chinatown (1964), Olga’s House of Shame (1964) and Olga’s Girls (1964). Friedman and Lewis gave it a shot with Scum of the Earth (1963), where models are blackmailed into taking kinky photos, but it didn’t quite stick.

“Gradually we became aware (the market told us, if nothing else), that one of two things were going to happen,” said Lewis (Morton / Juno, 1986). “We either were going to have to strengthen the kinds of films we were making, making them less and less ‘socially acceptable,’ or do something else.” So, “We sat down and made up a list of the kinds of films the major companies either could not make, or would not make. And on the list, staring us in the teeth, was gore.”

Said Friedman (McCarty, 1995), “While we were down in Florida shooting Bell, Bare and Beautiful, we got the bright idea to shoot Blood Feast (1963). We made it in four days using the same crew; it cost $26,000. That was the first of the blood-and-guts films, all the slice ‘em and dice ‘em, smash ‘em and mash ‘em films that ever came down the pike.”

I touched on the production and release of Blood Feast -- the tale of a mad cannibal caterer with an Egyptian fetish -- and its aftermath in a review of Two Thousand Maniacs (1964) over at the old bloggo. The film itself is just awful -- Lewis would later insist the film was not made, but excreted -- but the buckets of Kaopectate-fueled blood and rendered body parts struck a chord. Audiences had never seen anything like it, and they turned out in droves. Friedman’s wife called it vomitous, inspiring her husband to hand out complimentary barf bags to anyone who bought a ticket in case they got sick.

As the money rolled in, Stan Kohlberg, the principal financier who put up that $26,000, told Friedman and Lewis to quickly make another one; and they did, two actually, completing ‘The Blood Trilogy’ with Two Thousand Maniacs and Color Me Blood Red (1965). Alas, that would be the end of their collaborations as all that blood started to curdle and their partnership hemorrhaged out.

Like with all break-ups, the schism between Friedman and Lewis was over money. See, Kohlberg had talked Friedman, Lewis and executive producer Sid Reich into investing all the money made off of the Blood films into one account, which he would then use to secure a loan to fund a permanent film company for them. Turns out this was all a ruse and Kohlberg had been skimming profits from the bottom and off the top.

Thus, Friedman, Lewis and Reich filed suit against Kohlberg. But as the lawsuit dragged on indefinitely, Reich unexpectedly died, and Friedman would settle out of court without consulting Lewis, who considered this a betrayal, which, of course, officially ended their seven film partnership and their friendship until the two reconciled in the early 1980s. Both men would continue making films on their own in the 1960s and ‘70s, but their individual output suffered greatly from each other’s absence in my opinion.

Even before the blow-up with Kohlberg, cracks in their relationship were already starting to show. Friedman thought their product needed more polish to compete for the ever-dwindling exploitation markets, while Lewis didn't see the need to lessen profits by spending any more money on these no-frills productions.

After the split, Friedman left Chicago and the gore behind and migrated to California, where he would once again lean into the softcore skin-flicks, initially teaming up with frequent Bob Cresse collaborator Lee Frost on The Defilers (1965). “I wrote that one after reading John Fowles' novel The Collector about a kidnapping,” said Friedman (McCarty, 1995). “I rehashed it into a story about two rich punks out for kicks who kidnap this young girl who just arrived in Hollywood and rape her. The picture had all the elements -- nudity, violence, street language, kids smoking dope, you name it.”

Cresse and his Olympic International Films was also in the skin business with titles like House on Bare Mountain (1962), Hot Spur (1968) and the original Nazisploitation “classic” Love Camp 7 (1969), whose career in sleaze and ignominious end we already chronicled here. (It’s worth the read. Trust me.)

All of those films mentioned were directed by Frost and co-written with his long time partner, Wes Bishop. After Olympic International went belly-up, Frost and Bishop had a brief stint with American International -- Chrome and Hot Leather (1971), The Thing With Two Heads (1972) -- before latching onto Harry Novak and Crown International for things like Chain Gang Women (1971) and Policewomen (1974).

The Los Angeles Times (June 1, 1974).

Friedman, meanwhile, would go into business with Dan Sonney and formed Entertainment Ventures Inc for a series of what he called “crotch-grabbers.” And one of their first releases was Hell Kitten, which was just a re-release of The Prime Time under a new title and marketing campaign, which Friedman owned the rights to.

But they followed that up with the more ambitious costume drama, the X-Rated The Notorious Daughter of Fanny Hill (1966), which was soon followed up with more period pieces like The Lustful Turk (1968) and Trader Hornee (1970); a pirate movie, Thar She Blows! (1968); several westerns, including Brand of Shame (1968) and The Ramrodder (1969); a Sci-Fi epic, Space Thing (1968); and an ersatz rock musical called Bummer (1973), which touted “you don’t have to (sexually) assault a groupie, you just have to ask!!”

“The great thing about soft-X films was that you could advertise in Daily Variety and The Hollywood Reporter for casts, and you would get some of the most beautiful looking girls, who wanted to be actresses, to come in and test,” said Friedman (McCarty, 1995).

“You told them there would be nudity involved, but no sex, and that was no problem with them. And because they weren’t hardcore, they could also play in general release theaters and drive-ins, too, so there were a lot of outlets for them. There was no stigma attached to shooting soft-X pictures in Hollywood. You weren’t always looking over your shoulder waiting for the LAPD to show up, as was the case with hardcore. Soft-X was a bona fide industry, a big industry, in Los Angeles at the time.”

The Buffalo News (October 14, 1969).

As to why his softcore pictures succeeded while others failed? “Most people are making pretentious garbage,” said Friedman (ibid). “I make funny garbage.”

Now, most of his features were either written or co-written by Friedman himself, “which may explain why most of [his] films are as rigid as a medieval morality play: a heterosexual scene, an S&M scene (Friedman always had a thing for whips), and a lesbian scene, something for everyone.” Well, not really everyone, Friedman would confess. They were mostly for lonely men. Said Friedman (Morton / Juno, 1986), “I must admit the carny in me plays on that basic emotion that conmen use -- loneliness.”

But with the release of Deep Throat (1972), Behind the Green Door (1972) and The Devil in Miss Jones (1973), hardcore suddenly went legit, ushering in the era of Porno Chic. As we pointed out, Friedman never considered himself a pornographer and wasn’t a fan of the “anatomical explicitness” of this new breed of film, preferring a little more plot in his porn. Remember, to him, it was about the tease to keep bringing the customers back, but how do you do that when you give the whole game away in the first reel?

Friedman sort of dipped his toe into something a little harder when Andre Link and John Dunning reached out, looking for an assist on making the notorious Ilsa: She-Wolf of the SS (1974). Link, Dunning and their Canadian based Cinepix films started out in the skin business, too, but would later transition into horror with David Cronenberg’s They Came from Within (alias Shivers, 1975) and Rabid (1977) and the early Canadian Tax-Shelter Slashers My Bloody Valentine (1981) and Happy Birthday to Me (1981).

Friedman would produce the film and handled a lot of the logistics, including securing the use of the old Hogan’s Heroes sets (1965-1971), which were still standing, and casting Dyanne Thorne to play Ilsa after Phyllis Davis backed out over script vulgarities; but the production proved so tumultuous as the promised money from up north kept disappearing or got delayed indefinitely, that Friedman washed his hands of the whole thing during post-production, shipping all the completed materials up to Canada to let them finish it, and had his name removed from the credits.

Meanwhile, William “Bill” Castleman had joined Friedman’s merry band of sexploitationeers by providing the soundtrack for The Defilers. He would do the same for She Freak (1967) and The Acid Eaters (1967).

Castleman would then expand his horizons a bit at Entertainment Ventures by producing the likes of Thar She Blows, Starlet (1969), and Trader Hornee. Thus, by the 1970s, Castleman had become one of Friedman’s most trusted and valued employees, who then allowed his protege to try his hand at directing one of their pictures.

Castleman would be an uncredited co-director with Robert Freeman on The Erotic Adventures of Zorro (alias The Sexcapades of Don Diego, 1972), which presaged the George Hamilton vehicle, Zorro: the Gay Blade (1981), by having the masked vigilante’s alter ego, Don Diego, be an open homosexual. Castleman would also co-produce and direct Bummer!, which an IMDB user review rightfully called “one shag-carpeted, Mylar wallpapered, bong-water scented piece of a time long gone,” wrapped in a narrative that once again proves there is no such thing as a consensual rape.

Castleman also drew the short-straw and would serve as a messenger between Friedman and Cinepix during the Ilsa fiasco. And once that all fell through, unsure of what to do next, Castleman managed to convince Friedman to take a shot at legitimacy and make their first non-pornographic feature film.

Thus, needing a new genre to exploit, Friedman and Castleman ultimately looked to mimic the popularity and (hopefully) box-office success of two films: Phil Karlson’s Walking Tall (1973), where sheriff Buford Pusser (Joe Don Baker) and his handy whompin’ stick took on the State Line Mob and busted some skulls to liberate his town from their ingrained corruption; and Tom Laughlin’s counter-culture touchstone Billy Jack (1971), where the title character, an ex-Green Beret half-breed Navajo turned pacifist (Laughlin), defends a commune of hippies from a corrupt Sheriff and racial discrimination by putting his right foot into several rednecks’ left ears -- and they didn’t even see it coming.

The Los Angeles Times (February 23, 1973).

Both films were independently produced; both lead characters / anti-heroes would become cultural phenomena; and both would spawn franchises -- Walking Tall Part II (1975), Walking Tall: Final Chapter (1977), and The Trial of Billy Jack (1974) and Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977) respectively, not to mention a re-release of The Born Losers (1967), which featured the character’s debut.

Both films made a ridiculous amount of money compared to their budgets, too, with Walking Tall costing $500,000 and bringing in over $40 million and Billy Jack coming in at $800,000 but cashed-out with over $60-million at the box-office despite its tempestuous production history.

Now, Billy Jack was kind of a contemporary exclamation point on a wave of revisionist films that began to question the Anglo-centric version of the wild, wild west. As the 1960s progressed, the Western began to evolve and muddy the waters a bit, becoming an effective template for thinly disguised allegorical tales for rising racial tensions and the current conflict in southeast Asia, holding a mirror up to audiences, forcing them to watch man’s inhumanity toward his fellow man over differences of color, culture or creed that went well beyond the usual “Noble Savage” tropes.

Some of this was influenced by the Italians, but things were getting grimmer and more explicit domestically, too. Director Ralph Nelson made the most of these notions with the excellent Duel at Diablo (1966) and Soldier Blue (1970), where audiences were asked to reevaluate as to who really was the “bad guy” when it came to confrontations between Cowboys and Indians, which paved the way for Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970).

But there are just as many tales of murder and torture and cannibalism when the Native Americans fought with each other long before any European settlers arrived that would make your skin crawl. And this aspect, too, started to show up in Westerns as far back as the 1950s, with films like Broken Arrow (1950), where Jimmy Stewart is forced to watch a band of Apaches torture and kill some trespassing prospectors, or the startling scene of Sheb Wooley impaled and staked out on a tree as bait in Little Big Horn (1951).

As things moved into the 1960s and ‘70s, things got even more graphic, where the camera seldom flinched during the saber-skewering, raping and pillaging, making them a primitive version of Torture Porn with the likes of Chuka (1967), Shalako (1968), Cry Blood, Apache (1970), A Man Called Horse (1970), and Ulzana’s Raid (1972). Nelson was guilty of this, too, making them borderline atrocity pictures, really, tempering any progress that had been made on who the real savages were.

Regardless, Friedman and Castleman had their new genre to exploit while also getting back to his roots with the blood-letting. And like Billy Jack, Johnny Firecloud would also be an equally disenfranchised combat veteran, who was born on the day of the first Atomic bomb detonation, giving him his name.

Couple that with the inherent racism against Native Americans, and the fact the bigoted local land baron has it out for him for “defiling” his only daughter -- and out for him so badly he has no compunctions on taking it out on those Firecloud holds dear, including said daughter -- Wilton Denmark’s script basically wrote itself from there.

Denmark was known mostly writing scripts for episodic television with only one other feature film on his resume: Cain’s Cut-Throats (alias Cain’s Way, 1970), another, familiar tale of “Vengeance, Violence and Violation” for Joe Solomon’s Fanfare Productions. Still, Denmark managed a few surprises in Johnny Firecloud, starting with a timely intervention from an unsuspected source.

And to find out what that source is, Fellow Programs, you'll have to tune back in for Part Two of our Two-Part series on Johnny Firecloud, where the Road to Revenge is once more on a very slow and sometimes baffling turn.

%20by%20Robert%20Lindeaux.jpg)

_04.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%201972_5.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment