Due to a recent rash of guests vacating the premises without paying their bill, the manager of the luxurious seaside Grandview Hotel orders his head of security to track down these delinquent deadbeats so they can collect what they’re owed.

But Rick Stewart’s investigation goes nowhere fast, as he’s unable to find any trace of these three spongers, who apparently fell off the face of the Earth after skipping out on their tabs.

As a former cop, Stewart (Bailey) gets even more suspicious when he discovers a familiar pattern with these strays. None of them were seen in the hotel, at all, after they were first checked in and left in their rooms by a certain moonlighting bellhop. That and the fact that these three missing persons were (1) all female, (2) all had the same build, (3) were all considered pretty, and (4) were all blondes, have (5) gotten Stewart’s old detective instincts buzzing.

But when he suggests foul play might’ve been involved, the fussbudget hotel manager, Simmons (Bowen), won’t hear it. In fact, the more evidence Stewart finds that something criminal might’ve happened, the harder Simmons works to cover it up. Thus, fearing such notions would cause a scandal that would besmirch the hotel’s sterling reputation, Simmons decides to just let it go and write off those losses.

Meanwhile, Stewart isn’t quite ready to give up on these nefarious notions quite yet, but he’s soon distracted by the arrival of Lisa James, the lead singer of the hotel’s new resident house band.

Now, Stewart and Lisa (Bolling) have a complicated history. The two used to be married, but are now acrimoniously divorced. Apparently, things fell apart right after Stewart quit the force in disgrace after he shot and killed the wrong suspect. And just when he needed her most, Lisa’s developing singing career drew them even further apart and eventually cratered their marriage.

Upon her arrival, Lisa also draws the interest of a shy hotel maintenance worker named Jason Gant (Roberts), who runs the spotlight during her musical performances, and a shifty lifeguard named Hank Lassiter (Byrnes), who just so happens to be the guy who last saw each victim before they mysteriously disappeared.

There’s also a slight spark remaining between Stewart and Lisa, too, that might be stoked back into something hot if Stewart finally swallows his pride and settles his missing persons case -- not necessarily in that order.

Here, it should be noted that Lisa matches the exact physical description of the other missing women with one notable exception: she’s a brunette, not a blonde. But! When she performs, Lisa dons a long blonde wig, making her an exact match.

This is bad news for our singer because, as it turns out, Stewart was right to be concerned. For there really is a deranged killer running loose in the Grandview; a killer who's already got his sights locked onto Lisa as his next victim; a victim just like all the others; a victim who will check in, and then never, ever check out…

As the legend goes, writer, director and producer Richard L. Bare first got the idea for Anamorphic DUO-VISION while driving from Los Angeles to his home in Newport Beach.

Seems as his mind wandered, he noticed the dividing line on the pavement, and how the freeway lanes had two distinct but parallel perspectives when looked at with just one eye open at a time.

“I was driving home one day and as I glanced from one side of the freeway to the other, I noticed how my mind was taking a picture over here, then another over there,” said Bare in an interview with Bob Thomas (The San Francisco Examiner, December 24, 1972). And he thought, “Why not tell a film story with two simultaneous images?”

And this resultant mind-blow planted the seeds of an idea to make one movie from two totally different perspectives, for both eyes. Think Rashomon (1950) but in real time and all at once.

Born in Turlock, California, but raised in Alameda, Richard Leland Bare knew early that he wanted to get into showbiz, building himself an elaborate theatrical stage with a working curtain and lighting in his parents’ attic.

He would attend the newly minted University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts in the early 1930s, hoping for a career as a cameraman or an editor, where Bare’s senior thesis, an adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's The Oval Portrait (1934), won him the Paul Muni Award for Best Amateur Film. (Last check, this silent short was available for viewing on YouTube. Fair warning: the quality of the print is not great.)

Bare then dropped his amateur status when he sold his first screenplay to C.C. Burr, who was somewhere between running Mammoth Pictures and Puritan Pictures at the moment, which resulted in Two Gun Troubadour (1939), a singing sagebrush murder mystery for the "silvery voiced buckaroo" Fred Scott.

From there, he signed on at Warner Bros, where Bare initially found a home in the shorts department. Here, he wrote, produced and directed a staggering sum of the Joe McDoakes “So You Want to…” comedy one reelers, featuring George O’Hanlon as the title misfit. (If O’Hanlon sounds familiar to you, he would go on to voice George Jetson).

This run began with So You Want to Give Up Smoking (1942) and ended with So Your Wife Wants to Work (1956) with over 50 others in between, including such topics as So You Think You’re Allergic (1945), So You Want to Be a Detective (1948) and So You Think You’re Not Guilty (1950).

This amount would’ve been even bigger but Bare had enlisted in the Army Signal Corps in 1943, where he would serve as a member of the First Motion Picture Unit at Fort Roach. There, he made instructional and morale shorts for the enlisted men until he was mustered out at the end of World War II in 1945.

Three years later, he would get his first shot at a feature with some low-rent Middle East intrigue in Prisoners of the Casbah (1948); followed by a couple of vehicles for Virginia Mayo, Smart Girls Don’t Talk (1948) and Flaxy Martin (1949). In the first film, Mayo plays a socialite who gets in bed with a notorious gambler to solve her financial woes, only to have a change of heart after witnessing his homicidal tactics firsthand and helps the police bust-up their rackets. In the second, she plays a femme fatale, who helps frame an attorney for murder, who then escapes from jail and heads down the road to revenge.

Meanwhile, in The House Across the Street (1949), Wayne Morris plays a disgraced newspaper reporter, who tries to get back in the good graces of his publisher by bringing down a local mobster. And This Side of the Law (1950) sees a drifter (Kent Smith) conned into posing as a lookalike for a dubious inheritance grift.

There were also a couple of westerns with Return of the Frontiersman (1950) and the Randolph Scott led Shoot-Out at Medicine Bend (1957); and an earnest but awkward attempt to unravel the causes of racial strife and teenage gang wars in This Rebel Breed (1960).

But Bare’s biggest career break was probably directing the feature Girl on the Run (1958), where private investigator Stuart Bailey (Efrem Zimbalist Jr.) is hired to track down a singer who witnessed a murder, and then protect her from the same killer -- who had hired him to find her in the first place!

Now, technically, Girl on the Run was a TV pilot written and produced by Roy Huggins. Huggins was a left-leaning novelist turned screenwriter, and then producer, who survived the Communist witch-hunts of the 1950s relatively unscathed. And by 1955, he switched to television, producing the hit TV westerns Cheyenne (1955-1963) and Maverick (1957-1962) for William T. Orr.

Orr was Jack Warner’s son-in-law, who was put in charge of the studio’s new TV unit in 1955, where he produced programming for ABC. Now, ABC had been getting absolutely pasted in the ratings since its inception in 1948 until Orr successfully launched that series of prestige westerns; a novel shared universe which also included Colt .45 (1957-1960), Sugarfoot (1957-1961), Lawman (1958-1962) and Bronco (1958-1962).

But by 1958, Orr was looking for something a little more contemporary and charged Huggins and Bare to come up with a new detective series.

Now, Bare had worked with Orr before, back when Orr was still an actor and Bare was in the service. Orr had starred in the infamous Three Cadets short, which concerned the spread of venereal diseases. And Orr would also star in Bare’s Emotional Reactions, which dealt with the temptations of alcohol and prostitutes, where Orr was cast as a drunk.

Here, the running feud between Jack Warner and Huggins over proper compensation for the characters he created reared its ugly head, when Warner had the studio release the pilot of this new series as a theatrical feature first. This gave the studio a dubious legal loophole to screw Huggins out of the royalties he was owed.

Thus, Girl on the Run would go to series as the more familiar 77 Sunset Strip (1958-1964). And like his westerns, Orr’s new program was a smash hit and would also see its share of spin-offs with Bourbon Street Beat (1959-1960), Hawaiian Eye (1959-1963) and Surfside 6 (1960-1962). And during the height of his run, Orr had no fewer than nine prime-time programs on the air.

Richard L. Bare.

Working with Orr and Huggins, Bare would direct 21 episodes of Cheyenne, 11 episodes of Maverick, seven episodes of 77 Sunset Strip and a couple episodes of Lawman. And he would continue to work mostly in television throughout the 1960s with the notable exception of the rather insipid and self-explanatory I Sailed to Tahiti with an All Girl Crew (1969).

He would also direct six episodes of The Twilight Zone, including “Third from the Sun” (S01.E14, 1960), where a couple of government agents conspire to steal a rocketship and save their families from a pending nuclear holocaust; and in “Nick of Time” (S02.E07, 1960), a couple of newlyweds (William Shatner, Patricia Breslin) run afoul of a fortune telling machine at a roadside diner; but his most famous and familiar episode was probably “To Serve Man” (S03.E24, 1962), where a seemingly benevolent alien species get a little peckish for some terrestrial cuisine. (If you know, you know.)

(L-R) Richard Bare and Arnold Ziffel.

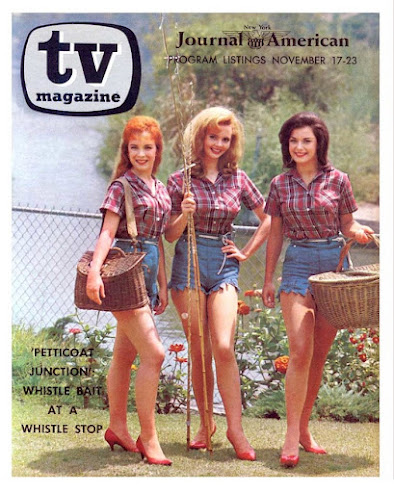

But where Bare really left his mark was when he landed at Filmways and got involved with the Hooterville Universe of Petticoat Junction (1963-1970) and Green Acres (1965-1971). Bare would handle 34 episodes of Petticoat Junction first before jumping over to the newer spin-off series, where he directed a staggering 166 of the series’ 168 episodes, including a streak of 137 straight.

But changes were coming at the dawn of the 1970s, as networks enacted what came to be known as “The Great Rural Purge,” where schedules were stripped bare of anything resembling a tumbleweed or a cement pond to make room for more urban, sophisticated, and socially relevant programming. And it was pretty brutal.

Petticoat Junction, Green Acres, Mayberry R.F.D., Hee-Haw (-- though this cornpone variety show would find a second life in syndication), and The Beverly Hillbillies all got the ax, along with westerns like The Virginian, The High Chaparral, Lancer, and The Big Valley, with the few stalwart survivors like Bonanza and Gunsmoke all coming to an end by 1975.

All of the networks were involved with this rural progrom, but CBS carried the biggest ax. As Pat Butram, one of the stars of Green Acres, famously quipped, "CBS canceled everything with a tree in it -- including Lassie."

Now rudderless, Bare would change directions for a brief spell, writing The Film Director: a Practical Guide to Motion Picture and Television Techniques, which was released in 1971 and became an essential nuts ‘n’ bolts text for those looking to get into the profession. And it was also around this time when Bare engaged in some willful recklessness while driving home on the 405 with only one eye open.

“I played around with the idea (of DUO-VISION) for two years before putting anything on paper,” said Bare (Thomas, 1972). “Then I decided to try the double technique with a psycho-drama I owned called The Squirrel.”

Dusting off the old, unsold script, Bare tore it apart and then slowly reassembled it to fit his parallel scheme after conquering a few logistical hurdles. “I needed a wide enough typewriter carriage to allow two scenes on every page,” Bare told Stanley Eichelbaum (The San Francisco Examiner, April 22, 1973).

“The script was done in double columns -- no easy task for any writer -- and it meant the scenes had to work out to the same split-second timing,” said Bare (ibid). “Timing became a major headache. I didn’t want to cheat and let one screen go dark, even for a couple of seconds.”

As for the grisly subject matter, said Bare, “I felt the process would work best for a psycho-killer drama in a campy, make-believe vein. It’s not to be taken seriously. I had in mind a mixture of Grand Hotel (1932) and Grand Guignol.”

As Eichelbaum pointed out, Bare’s idea was a little more advanced than the occasional split-screen techniques used by Richard Fleischer in The Boston Strangler (1968), Norman Jewison in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), and Robert Wise in The Andromeda Strain (1971), but an entire movie projected in two separate images. Thus, it was also noted how Bare had to be methodical laying out the action with a careful balance between the two screens.

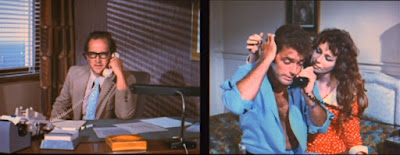

Knowing full well audiences could be overwhelmed by this new and untested technique, the decision was made early to make one side active, where the majority of the dialogue takes place, and the other side passive. (I'm hard pressed to recall a scene that had dialogue happening on both screens at once.)

“I didn’t want to bombard people with a double soundtrack for fear of confusing them,” said Bare (Eichelbaum, 1973). “I knew there’d be no trouble with the double image, particularly since we have a whole generation of kids who grew up doing their homework in front of the TV. They can digest and absorb a helluva lot more than audiences did in the old days.”

Grand Rapids Press (January 20, 1973).

Here, Eichelbaum elaborated on how Bare would use an assortment of techniques to achieve his split-screen effect, saying, at its simplest, the film shows cause and effect. On one side, a pretty girl checks into a hotel, goes to her room and prepares for bed. Meanwhile, on the other side of the screen, a killer stalks her in the lobby and then retires to his private lair to choose a murder weapon. “The audience,” according to Bare, “is now omnipotent.”

And that’s exactly how our film begins, when a woman named Dolores Hamilton (McBain) checks into the Grandview late one night.

As she registers at the front desk, someone starts spying on her from one of the many peepholes secreted in the crawlspaces and ventilation ducts that criss-cross the huge palatial hotel. And from his many secret vantage points, this stalker sees what room the new guest has been assigned to.

From there, we watch as the guest is taken to her room, where Dolores unpacks and prepares to turn in for the night on one screen, while the stalker sorts through his collection of blades on the other before finally settling on a large butcher knife. He then selects a certain key out of an assortment of many hanging on the wall hidden (we assume) somewhere inside a cavernous, unused part of the hotel.

Donning a bellhop costume and a hideous Halloween mask, the stalker then uses that key to quietly invade the woman’s hotel room, who is currently down to her underwear and is freshening up in the bathroom. There he waits in ambush until she comes out, and then proceeds to stab the woman to death rather gruesomely.

The brazen killer then orders some room service, which is delivered by Lassiter, who later relates to Stewart that it was a man, not a woman, who answered the door but then refused to open it until after he left. But the killer wasn’t interested in any food.

No.

He wanted the food trolley, which he uses to transport the body hidden

under the tablecloth; which he then wheels right by an unsuspecting knot

of other guests before he disappears, who failed to notice a bloody arm

sticking out the bottom.

And so, from the very beginning, Bare lets us know there’s a killer running loose within the confines of the hotel.

Then we have another split-screen flashback, where Simmons lists the guests who skipped out on paying in one frame, while the other reveals their grisly fate.

But it has to be someone who is intimately familiar with the surroundings, right? Right. Which immediately narrows down our choice of suspects despite Bare’s clumsy attempts to throw us off the track.

The director would also utilize DUO-VISION to show flashbacks and flash-forwards to solve the problem of the unreliable narrator. “The action is simultaneous, except in some scenes where I go back in time to show lies vs. truth,” said Bare (Thomas, 1972). “For instance, I have an old lady recounting how grandly she once lived; on the other screen we see that she had really been a hooker.”

Now, the old lady Bare’s referring to was Mrs. Lenore Karadyne (Sherwood), a long standing guest at the Grandview, who is currently delinquent on her own hotel bills by several months. A batty old dame molded in the image of Norma Desmond from Sunset Boulevard (1950), I didn’t really see Mrs. Karadyne as a hooker, more of a floozy or a flapper and a wannabe actress, who moonlighted as a stripper.

Either way, she was a relic and surrounded by antiques that had little value or no longer worked -- antiques the young, industrious Gant was willing to fix gratis for the destitute old woman, despite her tales of wealth and splendor. (He even sneaks money under her door on occasion.) In fact, he’s the only member of the hotel staff that doesn’t find or treat the older woman as an annoyance.

Thus, Mrs. Karadyne kinda serves as the mother Gant never had, who reveals how he grew up in a series of abusive foster homes -- each one worse than the last. But as they relate to each other how they wound up at the Grandview, we see through Bare’s twin-screen lie detector that Mrs. Karadyne’s wealthy husband didn’t die of a stroke as she claimed. Nope. She willfully killed him during a violent domestic dispute, covered it up, and had been living on the insurance payout until that money dried up about six months ago.

But Gant’s flashbacks are even worse, as we see all the physical and emotional abuse he had endured over the years, including one foster mother who entices a confused teenage Gant into her bed for a little canoodling, only to be caught in the act by her husband -- who takes it out not on his wife but on the kid. And as he beats the shit out of the helpless boy, the wife, who instigated the whole thing, cackles maniacally as she joins in on the beating.

And if you’re thinking this jumble of psychosis and triggers was the perfect breeding ground for a psychotic killer, when I tell you the seductress was also a blonde, well, if it wasn’t obvious enough already, that pretty much cinches that Gant is our masked killer.

This is somewhat confirmed when Lisa makes her debut at the Grandview’s Starlight Lounge, and pops out from behind the curtain in that blonde wig for the first time. This, of course, sends Gant into a mental tailspin as he watches her strut her stuff and belt out some tunes from his spotlight, which is mixed with images from his myriad tormentors.

But Bare remained stubbornly persistent in his attempts to offer up some red herring to muddy the waters as the show ends and Stewart kinda blows his chance at rekindling things with Lisa.

Still bitter about their divorce, their detente barely lasts for one drink before she excuses herself over his abhorrent selective memory.

However, this does give the killer time to prepare for his next murder.

And so, when Lisa returns to her room, he’s there in his uniform and mask to ambush her. But luckily for Lisa, she manages to survive this opening attack. And as they struggle, her lucky streak continues as an ashamed Stewart calls her room to apologize for his loutish behavior earlier.

Here, when Lisa manages to kick the ringing phone off the hook, he hears her struggling and screaming that someone is trying to kill her, assures help is on the way, and then sprints for her room.

Meanwhile, the killer overheard all of this, too. And not wanting to get caught, flees the crime scene immediately. Once in the hall, he removes the mask to reveal -- more like confirm -- that Gant was indeed our killer all along, who then manages to slip away unnoticed before Stewart arrives and finds Lisa shaken, but unmurdered.

Now, when his script about a psycho-killer running loose in a hotel was finally finished, Bare would then take it and his ideas for DUO-VISION to his old buddy, William Orr, who loved the idea. “Sure it's a stunt,” said Orr (Thomas, 1972). “But you need stunts to get people out of the house and away from blockbuster films and Movies of the Week they can see on TV (for free).”

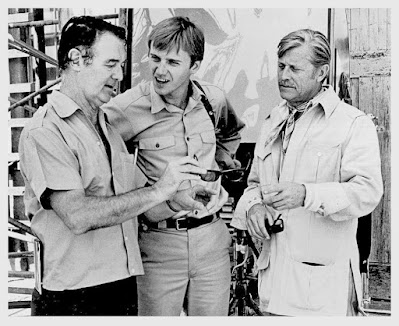

(L-R) Richard Bare, Randolph Roberts, William T. Orr.

And so, Bare and Orr would partner up and form United National Pictures, then took the script and the gimmick to a nearly moribund MGM, who were so desperate for a hit that they would’ve glommed onto nearly anything -- hell, at this point, they would’ve settled for a near miss, which would explain why Bare and Orr had a check for $1.5 million and a green-light to proceed on Wicked, Wicked (1973) in less than 48-hours.

The film would take 48 days to shoot, with the majority of it taking place at the Hotel del Coronado, which is located on Coronado Island just off the coast of California near San Diego. (I’ve been there, and it is beautiful.)

Construction on the massive, Victorian-style hotel broke ground in March, 1887, and held its grand opening in February, 1888. And over the decades since, it has played host to many celebrities, 12 standing U.S. Presidents, and (allegedly) the ghost of Kate Morgan, a visitor who died in 1892 under mysterious circumstances in room 502. Some say she's still there.

In the 1960s, the hotel was showing its age and the current owners sold the property to a developer, who originally had ideas to demolish the grand hotel and replace it with beachfront housing. But at the last minute, the hotel was spared and was instead refurbished and restored to its former glory -- and was still open for business at the time of this writing.

The venue made its big screen debut back in the silents with The Married Virgin (1918), and would be featured in the Billy Wilder comedy Some Like it Hot (1959), and later Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man (1980) and Herbert Ross’ My Blue Heaven (1990).

Bare would utilize every nook and cranny of the grand hotel; from the ballroom, to the rat’s nest of crawlspaces, to the rooms designated for refurbishments. To get all the footage he needed, Bare would be assisted by Donald Klune and Ronald Martinez. But when he started editing it together with John Schreyer, Bare quickly realized he still didn’t have enough footage.

“I also had to shoot 3000 more feet of film in order to fill a void on one of the screens,” said Bare (Thomas, 1972). And I have a sneaking suspicion the majority of that filler was the inclusion of the old woman playing the organ, who provides the diegetic mood music throughout the film.

The studio played it up big in the papers that Orr and Bare had acquired the use of the original score for the Lon Chaney version of Phantom of the Opera (1925) from rival studio Universal for their new film. The score would also include movements from Swan Lake (Tchaikovsky) and Faust (Gounod)

According to the press release (Greeley Daily Tribune, February 6, 1973), “The 48-year old score, which will be given screen credit, is played off camera by organist Ladd Thomas to create a mood for some of the new mystery thriller’s more dramatic and terrifying scenes.”

Thomas was a professor at the USC Thornton School of Music, and his efforts on the Wurlitzer are fine but ultimately played into Bare’s counter-productive notions of not taking the film too seriously. This roller-rink music not only torpedoes any tension, but makes the film come off as an overwrought, mustache-twirling melodrama / pantomime at best and teetering into the oblivion of self-aware parody at worst.

Ladd would be replaced on screen by Maryesther Denver, who, along with her apple, was played up as the comedy relief in another seeming act of self-sabotage by Bare.

When filming began, the director was smart enough to stick with the plan and not overload both screens at the same time. And on that front, DUO-VISION actually kinda-sorta works, especially in the scenes where the root cause of the killer's psychosis is revealed via a flashback on one screen while he slowly cracks up in the other.

Thus, from the very beginning, there wasn’t much of a mystery to Wicked, Wicked as we already know full well who the killer is, and why, which only leaves the lingering question: What was Gant doing with all the bodies?

Well, to find out the answer to that query, Boils and Ghouls and Fellow Programs of all stages, you will have to tune into Part Two of our Two Part look at Wicked, Wicked, where things get a little … Bonkers, Bonkers.

Originally posted on October 22, 2024, at Confirmed, Alan_01.

Wicked, Wicked (1973) United National Productions :: MGM / EP: William T. Orr / P: Richard L. Bare / D: Richard L. Bare / W: Richard L. Bare / C: Frederick Gately / E: John F. Schreyer / M: Philip Springer / S: David Bailey, Tiffany Bolling, Randolph Roberts, Scott Brady, Edd Byrnes, Roger Bowen, Madeleine Sherwood, Diane McBain

No comments:

Post a Comment