We're back in some familiar territory, the swamps and marshes of southern Arkansas, as our narrator gives us the nickel tour and waxes philosophically about the eerie serenity of these wetlands.

But all this natural serenity comes to a screeching halt when a large, primordial creature covered in long, coarse hair wanders into the scene near a river, starkly out of place against this pristine backdrop.

This is the legendary Monster of Boggy Creek; a Bigfoot-like creature that has haunted the area around Fouke, Arkansas, since the 1950s but has proven even more elusive than its cousin of the Pacific Northwest.

And while the narrator ponders if this creature is real or just a myth, upstream, a deer comes out of the forest to drink. Then, when the deer decides to go for a swim and cross the river, if you look real close, it appears to me that there's something looped around the buck's neck, meaning it isn't swimming -- but being pulled into the water and dragged across the river by the wire wrapped around its neck! (Allegedly.)

Here, this distressed deer only gets about halfway across before being forced into a holding pattern so we can spy a bubbling disturbance -- as if something was breathing under the water (-- or passing gas, perhaps?), chugging right toward it.

Using the ominous soundtrack as a clue, we quickly deduce that whatever's causing this disturbance isn't some friendly beaver; and when this bubbling wake finally overtakes the tethered deer -- that has now magically changed to a dead-deer carcass -- the animal gets thrashed around until a large clawed hand comes out of the water, causing the deer to change form again, this time into a mounted prop-head, that pukes up a vomitous cone of blood as the monster finishes throttling the animal before slowly dragging its prey underneath the water.

Then, all is silent as the water's surface turns placid -- until the deer's dismembered head bobs back to the surface! Cut to the shoreline, where we see the monster emerge, dragging the bloody and headless carcass behind him into the trees.

With that, our story proper begins at the University of Arkansas, where we find Dr. Brian Lockhart at a football game, cheering on his beloved Razorbacks.

As a tenured professor of anthropology, apparently, “Doc” Lockhart (Pierce) always had a keen interest in the local legend of the mysterious and elusive Fouke Monster. And so, when he receives word from Tim Thorne, one of his grad assistants, that there has been a rash of recent sightings of the creature, Lockhart, who firmly believes this cryptid is not a hoax, decides it's high time to lead an expedition into the swamps around Fouke and get some hard proof of the creature's existence.

With that, Lockhart, along with Tim (Pierce Jr.), Tanya Yazzie (Hedin), another grad assistant, and her "citified" friend, Leslie Walker (Butler), load up all kinds of sensors and scientific equipment into their jeep (-- but note not one single camera), and with a camper in tow, head out towards Fouke and the monster's old stomping grounds.

Needing some supplies and ammunition for his rifle, the expedition makes a pit-stop in Fouke. It’s never made clear, but I don’t think Lockhart has set out to capture the beast, or kill it as proof, but to study and document the unverified primate in a clinical sense in its natural environment -- like a bayou Jane Goodall. Thus, when the clerk of the general store asks if they’re all going camping, Lockhart proclaims that, no, they’re actually on a monster hunt.

Now, this revelation triggers a fit of laughter from the knot of locals gathered there, who all clamor there ain’t no such thing ‘round these parts, and derisively point out that drunks, kooks, and city-folk like them wanting to get their names in the paper are the only ones to have ever seen this ‘so-called’ monster.

In response, the scowling Lockhart gives them all a self-righteous stare of indignation that would vaporize glacial ice. And when another local pipes up, saying maybe they ought to get a monkey suit and raid the college-boy's camp, Lockhart's indignation finally boils over into full blown hostility, as he warns them all that he does believe in the monster. In fact: the beast scares him; and who knows, he might even be so scared that he'll shoot anything that even remotely resembles a monster if it gets too close to his camp and ask questions later.

Sweeping the room with his death-scowl of indignity one last time to punctuate that threat, Lockhart takes up his ammunition and leaves. And if you listen real close, there, Doc, as you vacate, I imagine you can hear those locals rightfully calling you an asshole, and debating on whether to break out their own shotguns and pay a house call on your camp anyway -- without a monkey-suit.

Wishful thinking on my part? Perhaps. Anyhoo.

After leaving those unbelieving heathens behind, our troupe of ersatz quest knights drives on until Lockhart tells Tim to stop at the next farm, which once belonged to W.L. Slogan, who had a close encounter with the creature some 30 years ago.

Here, while Lockhart recounts the story, someone smears Vaseline all over the lens, triggering a myopic flashback, where we spy Slogan (Vanderburg) bringing his dairy cattle in for the night. When he hears something in the barn and takes a look inside, there, silhouetted in the light, is the monster watching him! Startled, Slogan beats a hasty retreat.

His story / flashback done, the group heads on down the road, when suddenly, Tim slams on the brakes to avoid a deer carcass splayed across the middle of the highway.

As Lockhart and Tim drag the deer off the road before someone has a wreck, upon closer inspection, they notice the deer's head is missing, torn clean off, and how something had been gnawing on the remains. Was it a bobcat? Or was it the creature? Cue ominous music sting!

Moving on, and after turning off on a country road, Lockhart's crew finally finds a suitable clearing and makes camp. Later, around the campfire, as Tim sketches the creature (-- and we really wish Tim would keep his shirt on because he appears to have a vestigial third nipple that's a little distracting once you notice it), Lockhart says it's an accurate rendering.

This notion of the creature in the drawing actually existing scares the (-- and the movie can't stress this enough --) citified Leslie. But country-gal Tanya (-- rather disturbingly --) finds the beast sexy. (And we're not even going to touch that one, and we'll just allow that statement to stand on its own merit.) Luckily, we don’t ever venture into Nights with Sasquatch territory -- not that the hot-to-trot Tanya wasn’t willing. (More on this notorious novel in Part Two.)

Once Tanya gets her libido for tall, dark, and hairy monsters under control, Lockhart starts theorizing, saying with all the rain they’ve been having lately, he is confident that there’s a golden opportunity here to find the elusive creature. Noting that the creature has never been spotted during a drought, Lockhart believes when the river floods the lowlands, it drives the creature out to higher and dryer ground.

And with no time like the present, he loads everybody back into the jeep so they can get acquainted with the area before the sun sets. First stop is an abandoned homestead, where the crew get out to investigate a derelict house -- but are interrupted when a rabid dog bounds out of the woods and attacks them!

Now, do these geniuses run for the jeep and escape? Nope. They run into the abandoned house. Well, Lockhart does go to the jeep and gets his pistol first, a big old honkin’ .44-Magnum, pops off a few rounds at the dog, but misses rather badly. And as the foaming-mouthed dog lays siege on the house, despite its decaying brain, this canine continuously outwits our heroes at every turn.

Then, as this reel-killing encounter continued, as Lockhart proves a terrible shot, I counted his rounds, expecting the six-shooter to magically reload itself (-- because there was no way in hell Lockhart had any spare ammo in those tight shorts he always wore.)

Thus, as I waited for the magic seventh, eighth and ninth bullets, Lockhart ceases fire and orders Tim to check the closet to find something to cover the now gaping holes he just blew into the floor. But Tim, being the idiot that he is, mistakes the back door for the closet, opens it wide, and comes face to face with the frothing dog.

Throwing Tim out of the way, when Lockhart pulls the trigger (-- and I'm just as shocked as you are), the gun clicks empty! Letting the dog back him into a corner, Lockhart watches as the others scramble out of the house and make it to the jeep. Idiot Tim grabs the rifle, then returns to the house and manages to shoot the dog just as it lunges for Lockhart.

Leaving the sick and mortally wounded dog to slowly bleed to death, they solemnly vacate the premises. (I'm sure only after Lockhart gave the poor canine one of his long, patented self-righteous death-scowls first.)

Upon their return to camp, Citified Leslie has had enough of roughing it and wants to head back to town and sleep in a hotel, which triggers yet another righteously indignant death-scowl from Lockhart, which quickly cowers her. He never promised this would be a picnic, says Lockhart, before returning to his notes and records.

But as he pages through the countless incidents with the usually docile creature, Lockhart is puzzled by the circumstances of the Otis Tucker incident:

Here, we break out the Vaseline-cam again and spy Tucker (Adkins), happily trundling down a back road at night until his truck suffers a blowout. After breaking out the jack, as he starts to put on the spare, Tucker starts to hear some strange noises.

As he shines his flashlight around, he doesn't see anything. But that's because the monster was right behind him the whole time! (Cue ominous music sting!) Slowly Tucker turns, and then screams as the monster lets out a high wurbledy-gurgle and attacks him.

Now, no one knows for sure what really happened to Tucker, says Lockhart, because he never regained consciousness after being found beaten up near his truck, and then died two days later at the hospital. His wallet was still on him, so robbery was ruled out; but something caved in his skull and tipped the truck over, off the jack, and into the ditch. (One more time with that ominous music sting!)

With the sun starting to set at long last, it's finally time to rig-up all those fancy sensors and computer equipment the expedition brought with them. Soon enough, a 200-meter perimeter of sensors surround the camp, all tied into a computer in the camper, which in turn acts as a radar station that picks up anything moving within the scanning range.

Here, Lockhart sends Idiot Tim and Tanya out in opposite directions to test the equipment. Sure enough, two blips appear on screen as Lockhart explains to Citified Leslie (and the audience) how the sensors are calibrated for certain weight specifications, which is why they don't pick up birds, raccoons and curious ‘possums.

With the test completed, after ordering his two guinea pigs back to camp, Lockhart watches the corresponding blips get closer to the center, when suddenly, a third blip appears. And whatever it is, it's really big, and moving really fast, and it's currently zeroing in on Tanya's position…

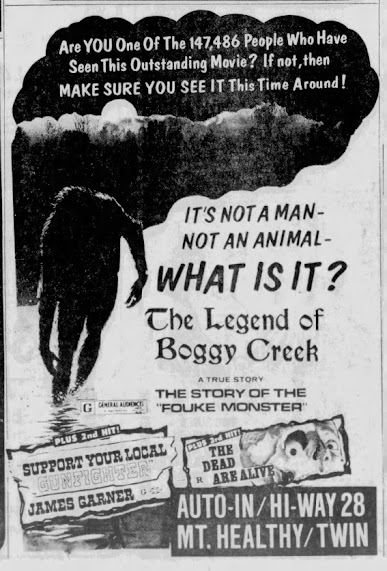

While completing his press tours during the initial rollout for The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972), Charles B. Pierce, the film’s co-producer, director, cinematographer, gaffer, soundman, electrician and best boy, bent over backwards to say he treated the locals around Fouke both decently and fairly, who willingly shared their stories and anecdotes that formed the backbone of his faux documentary, and how he did not embarrass them on screen as promised. But was he being honest?

“We were met with a lot of hostility,” said Earl Smith (The Camarillo Star, August 3, 1972), the film’s screenwriter. “The people down there had always been ridiculed and had a number of tongue-in-cheek stories written about their sightings of the monster. Their sight, sanity and sobriety had all been questioned in the past.”

As I mentioned in our earlier review of The Legend of Boggy Creek, where we got their side of the story, both Pierce and Smith spent a lot of time around Fouke interviewing people -- at least they were trying to, as most folks wouldn’t talk to these outsiders at all. Thus, they needed an insider to help break the insular ice and gain the locals' trust; and they managed to kill two birds with one stone when they contacted Julius “Smokey” Crabtree.

The other bird in question was access to Crabtree’s son, Lynn, whose encounter with the beast while out hunting was, aside from the Ford incident, the most well-known recent sighting -- back when the creature was still known as the Jonesville Monster. And Pierce felt it was the linchpin they needed to make his proposed movie work. (At the time of filming, Lynn was now too old, so Pierce subbed in his younger brother, Travis.)

A former merchant marine, Gold Glove boxer, and current oil pipeline welder, which saw him taking jobs all around the world, Smokey Crabtree was probably the best hunter and outdoorsmen in all of Miller County. He knew the bottomlands so well he didn’t even need the back of his hand. Crabtree was also well respected in the community and could open a lot of reluctant doors for P&L Productions.

“We saw a rather old model Cadillac car coming down the road,” said Crabtree (Smokey and the Fouke Monster, 1974). “The driver of the car was a skinny looking fellow. He was wearing short pants and sandals for shoes. His hair needed cutting badly, and he gave me the impression of a guy who needed a good round of worm medicine. He introduced himself as Charles Pierce.”

At the time, Crabtree was ‘live and let live’ when it came to the local legend. He had never actually seen it, but his wife and son had. He had only heard it, but felt the creature was docile enough and should be left alone. In fact, he always believed that the monster he knew was never near the Crank house, and felt the Fords had accidentally shot a neighbor’s errant horse, which had wandered onto the property in the dark, claiming the equine carcass was found not far from the Crank property the following morning, felled by a shotgun blast. His contention was the Fords then made up the monster story to cover their mistake

Already fed up with nosy sightseers drawn in by the publicity around the Ford incident, Crabtree was a hard sell. But he eventually signed on as a hunting guide and technical advisor -- as long as Pierce stuck to his promises that the people he talked to would be well compensated and not be played for fools over the stories they shared. Crabtree also tentatively agreed to let them document his family’s encounters but expected to be well compensated for it.

And so, with Crabtree acting as a mediator, “When residents realized we were going to tell it straight, they began cooperating and people who were afraid to mention their experiences with the creature began to step forward,” said Smith (Camarillo Times, 1972). “We uncovered details and incidents untold to that time.”

Unfortunately for Crabtree, what the exact amount of compensation would be for his invaluable assistance on The Legend of Boggy Creek was never settled as Pierce kept making up excuses while the interviews progressed and shooting commenced.

At first, according to Crabtree, Pierce was true to his word, paying people around $160 for their participation, including a signed release, and a promise to let each individual see their finished sequences and honor requested changes or have them removed altogether if they didn’t like what they saw.

But as shooting dragged on and money got tight, those payments became less and less, and Pierce even started shooting on properties without permission. Crabtree, meanwhile, wasn’t happy with the way Pierce was stretching the truth and for portraying the area as a rundown shithole filled with nothing but bumpkins and hayseeds.

Meanwhile, their salary negotiations were still going nowhere, as what Crabtree expected in payment wasn’t even remotely close to what Pierce was willing to pay.

Things came to a head about halfway through the production, when tensions got so bad between Pierce and Crabtree that he was fired off the picture. But! That also meant Pierce couldn’t use any footage of Crabtree, or his kin, or reference any of their stories in the film or face the possibility of a lawsuit since they had refused to sign a release until a bona fide contract on the compensation for his efforts was on record.

According to Crabtree, they tried to bamboozle him with one such contract, but it was so one-sided he refused to sign, which really sent negotiations into a terminal tailspin.

“They said we’ll just junk the film we have shot, rewrite the script and leave you all out of the picture,” said Crabtree (Smokey and the Fouke Monster, 1974). “I told them that would be a good idea since they were not willing to pay us for the trouble it would cause. So the great writer and producer stormed out of our house, mad at us because we asked them to treat us half decent.”

Of course, history shows that Pierce left all the Crabtree footage in. He made overtures to Crabtree before the film’s premiere, offering him a huge percentage on the next picture Pierce planned to make if he agreed to let them use his family’s contributions in the finished film and not cause any trouble.

“I figured he was lying about the partnership in the next picture but that would have to do for now,” said Crabtree (ibid). However, “I still did not know he had stolen all the footage on my lifelong friends and used it without paying them for it.”

The Cincinnati Post (July 13, 1973).

The Legend of Boggy Creek would go on to earn about $22-million on its release through Howco International. About $8-million of that went to P&L Productions, which was split evenly between Pierce and Buddy Ledwell, the film’s main financier and executive producer.

Originally, the split was to be 45-percent to Ledwell and Pierce and then 10-percent to Smith, but his percentage was bought out during the film’s four-walling phase -- a decision I’m sure Smith regretted to his dying day.

Crabtree, meanwhile, was well aware of these percentages and felt with everything he and his family had contributed, he deserved a 10-percent cut, too. But once the film was released, Pierce refused to take his phone calls and started hiding behind his lawyers. Crabtree and several others filed lawsuits against the producers. Most settled for peanuts, but Crabtree carried on. And after much searching by me, at the time of publishing, the outcome of this lawsuit remains undetermined. (Smokey Crabtree would pass away in 2016. Pierce in 2010.)

Of course, that kind of money always breeds hard feelings -- especially those left in its wake. As Pierce sat comfortably in his home in Texarkana, counting his money, and embarked on his next feature (without Crabtree), the town of Fouke was overrun by those hoping to see the now famous Boggy Creek Monster.

“I was informed that Pierce had lied to [the people of Fouke] in several ways,” said Crabtree (ibid). “He had not let them see the footage before it was used in the picture like he had promised. He had not made a final settlement with them on the amount of footage he used. Some of their stories had been stolen outright. They felt like he owed them a lot, and now they were borrowing money to see the picture.”

And since they couldn’t get to Pierce, they went after Crabtree. “I started talking to people in the Fouke area who had been contacted for help on the picture. What I found out I did not like. Most of the people were looking for me. They were quick to tell me how they had been lied to in order to have stories taken from them, and how Smith and Pierce had blown the story out of proportion, making them liars in front of their neighbors and friends.”

And feeling betrayed, most pointed the curious toward the Crabtree property to let them deal with it. “They all wanted something from the place where the movie had been shot, for a souvenir to take home with them.” And his property was so overrun, the owner suffered a nervous breakdown. But it wasn’t just the trespassers, but the overwhelming guilt over what he had caused. “I am to blame,” said Crabtree (ibid). “They could never have gotten into your house and convinced you [to participate] if not for me.”

As his lawsuit ground on, it took years to even find a lawyer to take the case, Crabtree toyed with the idea of making his own documentary to expose the truth about Pierce and the film. But when this proved too expensive, he decided to write a book instead. And when he could find no one who would publish it, he wound up publishing it himself

“I am not a writer, I cannot spell very well, but I wanted to tell a true story so bad that I sat down and actually wrote a book and you will never know the real truth about the Fouke Monster or The Legend of Boggy Creek until you read it,” said Crabtree (Shreveport Times, October 10, 1976). The handwritten book was called Smokey and the Fouke Monster (1975).

About half of said book is dedicated to recounting Crabtree’s upbringing, his love for the outdoors, and how he and his family wound up settling near Fouke. It reads pretty rough in spots on a technical level but it's engaging enough. However, Crabtree lays on the common man stuff a little thick; and his disdain and utter contempt for Pierce, Smith and Ledwell in the second half is palpable, so it all comes off as slightly biased and very paranoid -- Crabtree felt Pierce was in collusion with all the bankers and lawyers in western Arkansas, thwarting his attempts at restitution at every turn.

To mark the film’s 15th Anniversary, reporter Phil Martin visited Fouke; and when he bought a copy of Crabtree’s book as a souvenir, the clerk claimed to be Crabtree’s niece. “She told us that her Uncle Smokey had written the book in an effort to set the record straight about the Fouke Monster,” said Martin (The Shreveport Journal, July 28, 1987).

“There were, she said, some major points of divergence from the 1972 film,” reported Martin. “Smokey had worked as a technical adviser on the film and felt ill-used by the filmmakers. And, after the film’s success, he writes that crowds of tourists and monster trackers who overran his lands nearly robbed him of his sanity as well as his cherished lakeside serenity.”

Martin also gave a quick review, saying Smokey and the Fouke Monster was “a crude but oddly touching little book, filled with bitter personal judgements and inadvertent hilarity … It is a strange book, alternatively revealing and obstructive.”

The gist of it, said Martin, and I concur, was the Fouke Monster wasn’t the problem; no, the problem was with “the pestilence of the mythologizers and their carnival wake.” And Crabtree would never forgive Pierce and Smith for “exaggerating the Fouke Monster’s potential for evil.”

To make matters even worse, as early as 1973, a lot of other Fouke residents began to not only realize how they’d been taken advantage of but had also blown a golden opportunity to improve their small town’s economy by cashing in on the monster’s new found fame.

“Lots of people here in Fouke have missed the boat by not taking advantage of the publicity we have received and expanded on the monster theme,” said then current mayor J.D. Larey (The Abilene Reporter, August 22, 1973). “A novelty shop might have been the thing to bring in more money (from the tourists). But the people here just didn’t realize what they had when the iron was hot.”

The Little Rock radio station KAAY, who had offered a reward for the beast’s capture back in 1971, distributed more than 100 t-shirts that read ‘Fouke Forever.’ But only two local entrepreneurs managed to cash-in on the movie. One was the Boggy Creek Cafe, owned and operated by Bill Williams and his wife, where you could order a Boggy Creek Breakfast, a Three-Toed Sandwich, or a waffle and ice cream dessert called the Boggy Creek Delight.

And as you paid your check at the counter, Williams also offered souvenirs ranging from key chains, bumper stickers, and ashtrays emblazoned with the logo “Home of the Boggy Creek Monster.” Also available were miniature reproductions of the infamous three-toed footprint with a hand-painted “Welcome to Boggy Creek” on the base.

The second was Perry Parker and his brother Richard, whose stepfather, Tom Simmons, actually owned the Crank property and house where the alleged Ford attack took place. "Back when that first happened to the Fords, cars were lined up with people hunting for the monster," said Parker (Corsicana Daily Sun, August 22, 1973). "[His step-dad] had to put a barbed wire fence around the house because tourists had been going into it without permission."

Apparently, the house featured in the film was not the real one, as Simmons felt the offer of $2,000 to film there wasn't enough. Meanwhile, Perry had been charging up to $5 a carload for a guided tour of the real house and surrounding swamps. "I make a lot of money off it," said Perry. "People see the corn knocked down in the fields because the coons got in and ate it but they think the monster did it."

The Lafayette Daily Advertiser (December 7, 1976).

And there were others who were more than willing to cash in, too, even though the window of opportunity had practically collapsed already. This included Bob Gates and Tom Moore, who, perhaps in the interest of karma, pulled an end-run on Pierce and made their own sequel to The Legend of Boggy Creek without him.

Both Moore and Gates had assisted Pierce during the making of The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1976); Moore as an associate producer and Gates as a production manager. When filming wrapped in Texarkana, Gates and Moore bypassed Pierce and received permission from Buddy Ledwell to do a sequel about the Fouke Monster.

Unlike its predecessor, Return to Boggy Creek (1977) would not be shot as a documentary but a straight out adventure yarn. In fact, it takes place nowhere near Fouke or Boggy Creek as the action moves to the bayous of Louisiana, where a kinder, gentler monster known locally as Big Bay-Ty saves a group of lost children from a hurricane.

“We’re making a family adventure film here where the monster actually ends up saving the children,” said Moore (The Lafayette Daily Advertiser, December 5, 1976). “We’re trying to make the show in the old Walt Disney style of movies -- entertainment for the whole family.”

The Lafayette Daily Advertiser (December 5, 1976).

Ledwell’s sons, Stephen and L.W. Jr., along with Gates and Moore, would produce; Moore would also direct, and serve as co-screenwriter with John David Woody. Moore had some previous experience, having produced a couple of regional horror films shot in Texas: Mark of the Witch (1970), where the spirit of a wiccan possesses her way to revenge on the descendants of those who hanged her, and Horror High (1973), which was basically I Was a Teenage Jekyll and Hyde.

Horror High was pretty good, given its circumstances, but Mark of the Witch was pretty terrible on top of its circumstances. As for Return to Boggy Creek, well, no matter the circumstances, it certainly didn’t have the impact of Pierce’s film -- either culturally or financially, as the feature fizzled, got pasted by the critics, and quickly faded away.

Said Perry Steward (Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 11, 1977), “Charles Pierce, who took his Boggy Creek millions and went on to make more ambitious features, probably is sport enough to wish these poachers well. But the one time Texarkana ad man is certain to bristle when he learns that both legend and geography have been tampered with.”

Meanwhile, when Pierce was about to go into production on Grayeagle (1977), he mentioned in an interview with Lane Crockett how his latest western would be in the same vein as Winterhawk (1975) but not a sequel. “I don’t want to do a sequel,” said Pierce (The Shreveport Journal, April 8, 1977). “I don’t like sequels.”

But whether he liked them or not, there was a demand for one after the first film did so well. But, “I didn’t want to do another Boggy Creek -- not for a while,” said Pierce (Fangoria, August, 1997). “I was still trying to prove myself as a filmmaker; I didn’t want to have to turn around and shoot the same thing all over again. I wanted to do something different.”

And so he did, starting with Bootleggers (alias Dead-Eye Dewey and the Arkansas Kid,1974), which introduced the world to Jaclyn Smith, later of Charlie’s Angels fame, who got bumped to the top of the bill when it was rereleased as The Bootlegger's Angel. And while the film didn’t lose money, it was nowhere near a hit like Boggy Creek.

But Pierce was philosophical, telling The Calgary Herald (June 21, 1975), “The risk in doing motion pictures is like drilling for oil wells. Only 16-percent of all films made make a profit,” he said. “I realize that you won’t have a blockbuster, a Boggy Creek, every time. You just continue to do a quality film and bring it back into the black. If you keep doing that, eventually, you will get yourself another blockbuster.”

And he got one with his next feature, Winterhawk, the first of his elegiac westerns, which brought in about $14-million, but got lost in the wash of JAWS (1975), which would redefine what a real blockbuster was from then on. As would Greyeagle, which could only muster $2.5-million in the wake of Star Wars (1977), Smokey and the Bandit (1977), Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), which it opened against that December and Pierce never stood a chance.

In between those two westerns, Pierce would regroup with something he knew had worked before and hoped would work again; and while still not a sequel, The Town that Dreaded Sundown carried all the familiar earmarks of The Legend of Boggy Creek.

It was based on the notorious Texarkana Moonlight Murders, where eight people were killed by an unknown phantom assailant back in 1946. So, it was another tale based on a local legend, was told in the same docudrama style, was surrounded by an air of rustic authenticity, and whose central mystery left it up to the audience as to whether the killer, who was never caught (officially), was still alive and prowling the streets of Texarkana to this very day.

And while well received, and highly influential, The Town that Dreaded Sundown would only muster about $5-million at the box office.

Still, when American International Pictures picked up and released The Town that Dreaded Sundown, they were so pleased with the box-office return on the film’s $400,000 budget that they quickly signed Pierce to a multi-picture deal, where they would co-finance and provide distribution.

This netted them The Norsemen (1978), which was both awesome and terrible, and The Evictors (1979), which was pretty good, I thought, even though Pierce might’ve gone down that bucolic horror well one too many times by then.

Always one for recycling, AIP had hoped Pierce’s next contractually obligated film would be an official Boggy Creek sequel. But at the time, AIP was a ghost of its former self. They had recently merged with Filmways, and their co-founder, Samuel Z. Arkoff, would resign not long after. In fact, The Evictors would be one of the last films AIP would distribute before the once storied little studio that could ceased to exist.

His relationship with the studio was tumultuous at best and extremely bitter at worst, whose hands-on approach rankled Pierce greatly.

“I remember him getting so frustrated,” recalled Pierce’s daughter, Amanda Squitiero, in an interview with Daniel Kremer for Filmmaker Magazine (April 17, 2017). “He would carry on and say, ‘No one will ever tell me what I’m going to do on my motion picture. It’s my motion picture!’ It was always a ‘motion picture’ with him, rarely a ‘film’ and certainly never a ‘movie.’ He hated the word ‘movie.’”

After the financial disappointments of his last two features, and having lost his backing with AIP when they went under, Pierce would go quiet for nearly five years. And when he resurfaced in 1983, the filmmaker was ready to make a comeback with the long awaited sequel to the film that first put him on the map. Would lightning strike again?

Well, when you combine that bloody opening (-- where I suspect at least three deer were sacrificed to get that sequence in the river), with a full on and unadulterated view of the guy in the gorilla suit in the first reel (-- depending on which version you watch), we already know full well that we’re in for a far different kind of film than the first Boggy Creek movie.

Was abandoning the grounded, documentary style of its predecessor to the film's betterment or detriment? Well, let's be generous at this point and say the verdict is still out, as we still have over half of the movie to conquer yet.

However, judging by what we've seen thus far, this could get seriously ugly pretty damned quick. How ugly? Well, for that you’ll have to tune in for Part Two of our Two-Part look at the further adventures of the Barbaric Beast of Boggy Creek.

Originally posted on December 13, 2002, at 3B Theater.

Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues (1985) Aquarius Releasing :: Howco International Pictures / P: Joy N. Houck Jr., Charles B. Pierce / D: Charles B. Pierce / W: Charles B. Pierce / C: Shirak Kojayan / E: Shirak Kojayan / M: Frank McKelvey, Lori McKelvey / S: Charles B. Pierce, Cindy Butler, Serene Hedin, Chuck Pierce Jr., Jimmy Clem

%201973.jpg)

%201977_01.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment