After a failed raid to take out a German fuel dump, what’s left of a squad of American G.I.s are currently lost in the deserts of Tunisia, circa June, 1943, who are desperately trying to find their way back to Allied lines.

Now, one of the main reasons they don’t know where they are is that their bumbling Lieutenant was captured during the failed pre-credit raid, who was in possession of their only map. Luckily, they are still in contact with company headquarters via the pack-radio, who assure Sgt. Clemens that his squad is safely somewhere in Allied occupied territory -- they’re just not sure where exactly.

Ordered to hold his current guesstimated position by his commanding officer, and that another squad will soon be dispatched to round them up, Clemens (Gavlin) feels too exposed and orders his men to keep moving in what he hopes is in the right north by northwesterly direction. You see, there used to be six members left in his squad, but Private Slade (Hamilton) was just gunned down and killed by a German pilot on a strafing run. And so, while his commander doesn’t know where they are, the enemy Luftwaffe most assuredly does.

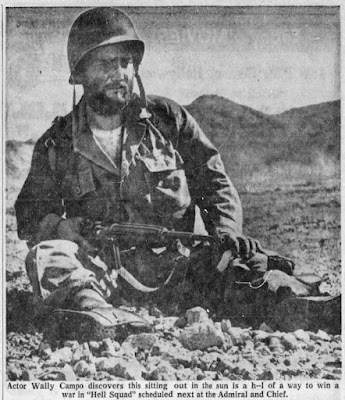

Thus, not wanting to wait around like sitting ducks, waiting to get shot to pieces, Clemens gets the rest of his grumbling men moving again. Included in this rag-tag bunch of stragglers are Roth (Schrier), the radio-man, along with three riflemen: the slovenly Russo (Campo), who is nursing a wounded leg, his buddy, Nelson (Stewart), and a young an extremely introverted harmonica player known only as Lippy (Addis).

Apparently, the harmonica belonged to Lippy’s older brother, who was killed during the Allied landings in North Africa as part of Operation Torch several months earlier -- which the young private witnessed. He hasn’t spoken since and just keeps playing the same tune over and over again.

Tragically, right before this “suicide mission” was launched, bemoans Clemens, word came that Lippy’s other brother was also Killed In Action, making him the only surviving sibling; and he was set to be discharged as soon as they got back on compassionate grounds. (Of course, this same scenario was the backbone of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998).

Alas, Lippy’s family’s bad luck continues as another German strafing run soon reduces the squad to four. With no time to bury him, Russo secures the dead man’s dog-tags and confiscates the harmonica. But upon reflection, he stops and leaves the prized instrument with the deceased, securing it in his hand.

Then, several sand dunes and washouts later, as the lost patrol presses on, they come upon the site of a massacre: several other G.I.s, stripped down to their underwear, bound, and all shot in the back. It’s a game the Krauts like to play, says an infuriated Clemens, stripping prisoners, forcing them to run to be shot while ‘trying to escape.’

Further inspection of the bodies is delayed over a fear of the dead being booby-trapped by the enemy. In the meantime, Clemens orders Nelson to scout ahead and make sure whoever committed this atrocity wasn’t still hanging around to do it again.

We then cut to what appears to be another American squad holed up in a nearby washout. But when Nelson appears over a nearby hill, as he’s waved down to join them, the squad commander whispers orders to the others -- in German! It’s a trap, and Nelson has just blundered right into it!

Unaware of this, and thinking this might be their rescue party, Nelson is greeted by the same officer, who now speaks perfect English. (And I’m thinking we all now know where those missing G.I. uniforms went, right?) Happy to see some friendly faces, the duped Nelson gives a full report on what’s left of his group, what their objective was, what they found, and the capture of their commanding officer. The fake Lieutenant (Sowards) then sends Nelson back to bring in the rest of his squad to link up with them.

But once he’s gone and out of earshot, so is the English, as the Lieutenant barks orders at his men to take up positions. Now all they have to do is wait for the verdammt Amerikaners to walk right into their carefully crafted ambush and eliminate them all…

In the resulting confusion during the manhunt for the assassin who shot and killed President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, while his motorcade passed through the Dealey Plaza, Dallas, Texas, Lee Harvey Oswald was stopped by patrolman J.D. Tippit in the neighborhood of Oak Cliff. Tippit stopped him because he matched the description of the main suspect who fled the Texas School Book Depository from which the lethal shots were fired. Oswald would then shoot the officer four times, killing him.

Several witnesses heard the shots and saw Oswald fleeing the scene with revolver in hand, including a shoe store manager named Johnny Brewer. Brewer would later testify that he saw the suspect temporarily take refuge in the alcove of his store entrance before slipping into the nearby Texas Theater, where he was later arrested after trying to shoot another officer while still inside the venue.

As for what was currently on the marquee, and the film that got interrupted while the authorities turned the house lights up and made their arrest? Well, the answer to that trivia question was Burt Topper’s War is Hell (1962), which critic Kathleen Carroll (Los Angeles Daily News, January 23, 1964), called “Another Korean War drama filled with paper thin characters, who play out the story of an ordinary heel who elects to buy his way to glory at the expense of the lives and horror of his fellow soldiers. The reason for his maniacal actions apparently rests on his plea that he has never done anything to be proud of, and for this he cuts a brutal swath to that all-important medal.”

When he was only 8-years old in 1936, Burt Topper’s family moved from Coney Island, New York, to Los Angeles, California. After serving in the Navy during World War II, according to Mark Thomas McGee (Fast and Furious, the Story of American International Pictures, 1984), Topper was working on a roof in Beverly Hills when one of his coworkers asked if he was ever interested in the movies. And since acting sounded like more fun than being a manual laborer, Topper decided to pursue a career in acting.

Los Angeles Evening Citizen News (October 27, 1952)

But he didn’t have much luck breaking into pictures. Said McGee, “He tried out for the lead role of Hiawatha (1952) but the part went to Vince Edwards.” Topper did manage to land a studio contract but, again, this didn’t really lead to anything.

He did have better luck on the stage, where he eventually latched onto a revival of Arthur Laurents’ The Bird Cage in 1952, where he played Wally Williams, the villain of the piece. “Wally is brought to the stage competently by Burt Topper,” raved the Los Angeles Evening Citizen (October 23, 1952). “A good looking young chap, who from time to time portrays the heel to the hilt.”

Los Angeles Daily News (August 28, 1954).

By 1954, Topper had joined the Academy Players, this time producing a revival of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. Said Roy Ringer (Los Angeles Daily News, June 1, 1954), "If their maiden effort is an indication of future policy, we can expect original and exciting theater from the Academy Players, a new company of actors / technicians who have taken over the red barn theater." And "While it has flaws, particularly in the physical staging, it also furnishes encouraging proof that producers Burt Topper, Jeanne Conte, George Berkeley and Michael Egan are not afraid to experiment with new dramatic techniques."

And it was around this time when Topper first met his future collaborator, Joyce King, and decided to take matters into his own hands on his future in showbusiness. Said King in an interview with Brian Albright (Wild Beyond Belief, 2008), “I was born in Hollywood, grew up in Eagle Rock, which is a suburb between Glendale and Pasadena. I went to Glendale Junior College and graduated from the Pasadena Playhouse College of Theater Arts.” As for how she met Topper, “We helped open the Horseshoe Stage in 1954. I was the stage manager, and Burt was the ‘when something had to be done’ person. And then one day (in 1957) he said, ‘Let's go make a movie.’”

Like Orson Welles and Edward D. Wood Jr. before him, Topper would be a triple threat, serving as producer, writer and director on his proposed opus, a war film, under the working title of The Ground They Walk. Said Topper (McGee, 1984), “If I was going to gamble, I reckoned that I might as well gamble on myself.”

And like in his theater work, Topper would also be "hands on" for everything else, too, as he told Tom Weaver (The Classic Horror Film Board, April 5, 2007), “In order to make it on a low budget, we sewed all our own uniforms; I built my own power units to power my camera; I built my own reflectors; and, oh God, I even built a camera dolly.”

The Tampa Times (December 10, 1958).

Like Topper, King would wear many hats for this low-budget production, too, including script supervisor, continuity, caterer and wardrobe. Initially, “I thought he was full of shit,” King told Albright. “What is this movie crap? Is he gonna chase me around the office now? No, he meant it. And for six months, with about 50 guys (-- there were only three women ever involved), we’d go outside of Barstow and go up in the hills and sort of built a camp.”

For the rest of his crew, Topper skipped the apple barrel and went straight to the non-union tree, recruiting USC film students to run the camera, record sound, handle the lights, and do the editing, making this the first feature for nearly everyone involved.

Said Topper (Weaver, 2007), “When I was doing The Ground They Walk, Bob Clarke was making a monster picture -- The Hideous Sun Demon (1959) -- the same kind of way, with a crew from USC. Clarke thought that Science Fiction was the thing that was selling and, yeah, actually, they were right; but I didn't know anything about Science Fiction. Anyway, that's how Bob and I became friends, when he did his Sci-Fi picture and I did the War story.” And Topper and Clarke would share a lot of the same amateur crew while filming.

Said King, “It was shot in 16mm, and like I said, it took six months, working on weekends only. Everybody contributed everything.” And, “Burt never asked anybody to do anything that he wouldn’t do himself,” she said. “And to the best of my knowledge, Burt Topper paid every single person every single penny they had coming.”

Like his later Korean War film, The Ground They Walk would eschew any kind of grand spectacle and was more of a character study, telling a small story in a big war, and keeping it nice and simple to stay within his means. The setting this time would be World War II during the North African campaign, about seven months after the successful landings of Operation Torch (November, 1942), and five months after the disastrous Battle of Kasserine Pass (February, 1943), which saw the American forces routed.

Strangely, Topper’s action would take place in June, 1943, one month after the capture of Tunis (May, 1943), which essentially ended the war in Africa and saw the surrender of what was left of the Afrikakorps. (Sorry, the voice inside my head that identifies as ‘The History Major’ kinda asserted itself and got away from me there for a bit. What? Don’t look at me that way. Don’t judge me. I paid a lot of money for that damned diploma.) Thus, we’ll assume Clemens and his squad were part of the efforts to mop up what little German resistance was left.

Now, in the aforementioned War is Hell, Topper’s psychotic squad leader ignores a cease fire order and sends his men to get killed anyway for his own glorification. Thus, there might’ve been a little hay to make out of all this in The Ground They Walk, too, morally speaking, if it turned out all of these men were wasted needlessly after the German forces had already officially surrendered.

Instead, we get a straight-up action piece that manages to overcompensate for its lack of budget with some genuine tension an effective low-rent thrills. Here, Topper keeps things humming along as each scenario is set up and then knocked down in what will, essentially, turn out to be a battle of attrition as Nelson returns and reports he found: another squad of gravel-agitators that wants to link up with them.But Clemens is no dummy and proves he earned those Sergeant stripes for a reason. And, well, turns out those Germans weren’t near as clever as they thought as the wily veteran sniffs out the possibility of their diabolical ruse by the number of men Nelson found matches the number of stripped bodies they discovered.

Thus, instead of just walking right into their camp, his squad stealthily circles around and approaches from the rear, confirming their treachery and catching them all waiting in ambush with their weapons and attention currently pointing away from them.

Proven right, Clemens then gets his squad positioned to catch the enemy in a crossfire. And after a few suspenseful moments of sneaking into position, the tables are turned and the enemy is wiped out save for the fake Lieutenant, who manages to hole up in a crevice and refuses to surrender.

At some point during this stand-off, Nelson is able to get the drop on him but struggles with pulling the trigger (-- something he has been struggling with for awhile now). But Russo has no such compunctions and tosses a grenade into the crevice, killing the enemy.

The battle over, Clemens regroups his squad and once more tries to contact Company HQ. And while he can’t raise them, he does make contact with a British outfit and they exchange approximate positions.

Here, the fickle hand of fate strikes. For while Clemens was able to sniff out the first German trap he failed to detect the second, as once again they’ve been suckered; this time by a Lt. Schlechter (Carroll) posing as an British officer over the radio, who lures them out into the open. Schlechter then orders his machine-gunner to open-fire (-- who appears to be his only subordinate).

Caught unaware, Clemens and Roth are immediately killed and Nelson is mortally wounded -- and he doesn't die easy. Only Russo is spared because he sat down to tend to his injured leg. And as he scrambles for cover on his belly, he is temporarily saved when a squadron of Allied bombers appear overhead.

With that, Schlechter moves to radio his own superiors about the impending bombing raid while he orders the other soldier to take his rifle and mop-up what’s left of the American patrol.

What follows is a fairly suspenseful game of cat and mouse as the opponents circle around each other in all the slit-trenches, gullies, and impact craters with their heads down, hunting each other by sound alone.

Here, Russo proves to have the better ears and manages to kill the other man with his knife. He then tosses a grenade into the German’s ersatz observation post, destroying the machine gun and taking out Schlechter and the radio.

As he searches the wrecked foxhole for some coveted matches, Russo finds a map that marks all the German positions in the area, which he stuffs into his shirt.

He then presses on, toward friendlier lines, when he suddenly stops and his eyes grow wide with fear as he scours the ground, spotting several tell-tale signs that he’s managed to walk right into a minefield!

Knowing his next step might be his last, Russo desperately tries to move back exactly the way he came. But in his panic he isn’t careful enough, triggering a mine, which damages his bad leg even further!

Meanwhile, back in the foxhole, turns out Schlechter wasn’t quite as dead as everyone thought. Revived by the sound of the mine’s detonation, he peers out the foxhole but comes face to face with the wounded and frantic Russo and his gun.

With about ten to fifteen feet between them, the unarmed Schlechter plays it cool, convincing Russo not to shoot, saying the percussion might set off another mine.

As they continue to talk, Schlechter reveals that he is a member of German Intelligence, who took advantage of the “hypocrisy of the British educational system” and studied abroad before the war started, explaining his perfect English. Unimpressed, Russo, realizing he is the one who suckered them over the radio and got his friends killed, threatens to blow his brains out in retaliation. Once again, the cool and calculating German encourages patience because he has an offer to make upon discovering Russo has taken his maps. An offer he feels the American can’t refuse.

Here, as this stand-off in the middle of nowhere continues, Schlecter offers to trade a map of the minefield for the map Russo stole. A desperate Russo eventually agrees and tosses over the coveted map, taking the German at his word that he will then do the same. But then Schlechter shows his true colors, scoffing at the foolish American for his idiocy -- he has no intention of surrendering his map, which earns him an abrupt bullet in the arm for his treachery.

Now, even though Russo promises the next bullet will go into his guts unless he tosses him the map, Schlechter refuses, saying they will have to just sit and wait, meaning the winner of this showdown will be determined over which side finds them first.

And so, they wait. But as tension mounts and the desert sun beats down, Schlechter asks permission to retrieve his canteen. When Russo grants him permission, the German retrieves it and starts to take a drink -- not realizing that this time he was the one being suckered as Russo fires again; only he wasn’t aiming at Schlechter but at his canteen, which is destroyed and all its precious contents spill out over the hot sand.

This action finally punches a hole in the cocksure Schlechter’s resolve as Russo now has the upper-hand in this stalemate. For now he has a carrot to dangle -- Nelson’s canteen, retrieved after he was killed, which Russo will exchange for the minefield map.

At first, Schlechter refuses to play along. But as time passes and the heat bears down, he soon becomes delirious; and in a desperate act, he starts tossing rocks toward Russo. Not at him exactly, but around him, hoping they will trigger one of the mines. When that doesn’t work, he finally relents.

Obviously, neither side trusts each other but Russo is able to rig-up a loop of disabled tripwire, which they each tie on the desirable object at an equal distance. The goal is to then circle the rope around "like a clock" until the object completes the circuit to the other man, which, in theory, should arrive at the same time. Even here, Schlechter screws with Russo -- for no other reason except that he can.

Despite this interference, they manage a successful swap. And once Schlechter drinks his fill, he helps the wounded Russo to his feet, who then holds him at gunpoint as he marches them both out of the minefield. Here, one can’t help but notice as Russo hobbles around on one leg behind him how Schlechter leads them as close to the mines as possible, hoping the other man will stumble and detonate one of them. And all the while, Schlechter will not stop with his taunting laughter.

Meanwhile, the American patrol that was sent out to find Russo and the others is circling ever nearer to them. But they’re not quite close enough as Schlechter manages to overpower Russo and steal his rifle. The German also steals his only remaining canteen and appears to be ready to abandon the wounded G.I. to the mercies of the desert and the circling buzzards.

But Schlecter doesn’t get very far before running into that American patrol, who then beats a hasty retreat back to Russo and holds him hostage, demanding the others surrender or he will kill their comrade. Here, the patrol surrenders, but not before sending the member of the squad that the German didn’t see to circle around the occluding hill and get behind him.

However, once he’s surrounded Schlechter still refuses to give up and opens fire -- only to discover that Russo’s gun is empty, having expended his last cartridge to puncture the German’s canteen several hours ago. And as that realization sinks in, we then fade to black over the sound of Russo’s mocking, maniacal laughter at the “superior” enemy’s failure to realize that he was several moves ahead of him the whole time and was being played all along.

Admittedly, the seams were showing throughout the run of Burt Topper’s inaugural feature, but I still contend that he and the rest of his amateur troupe managed to pull off a minor miracle. And he did this by keeping things simple and by squeezing everything humanly possible out of its meager budget, stretching those tens-of-dollars with a ton of kit-bashed creativity and a lot of chutzpah.

“We shot out in Indio, where the Army trained for desert warfare, and where they had all these trenches dug,” Topper told Weaver. As for how he managed to stage the invasion force’s beach landings for a flashback sequence, where Lippy's brother is killed, Topper really pulled something out of his posterior on that one to match the stock footage.

“I was in the Navy reserve,” said Topper. “So when I needed a shot of a landing craft with my people in it, we went to the base up at Oxnard, where I knew they had, in front of a museum, an old LCVP landing craft. I told them we were doing a training film and, by God, they saluted me and we got to go in. I had all my actors in the (stationary) landing craft, we got some sailors to get a hose for us, the hose squirted water into the landing craft like it was moving, and that's how we got that shot of the guys in the landing craft going onto the beach!”

Topper was even in charge of stunt coordinating and the film’s special-effects. Said Topper, “I did a lot of my own effects at that time, 'cause I had worked with explosives a little bit. At that time, you didn't even need permits, you could just go in and buy what you needed.” And then detonate it, apparently. Wow.

As for the gunplay, “I bought some bullet hits from Chuck Hanawalt, who was a friend of mine, and I used dynamite for the explosions,” said Topper. Hanawalt was a veteran grip, who was an integral part of Roger Corman’s production team, working on films like Day the World Ended (1955), Not of This Earth (1957) and Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957). “I also bought a little surplus machine-gun, had it de-wadded, and I bored it out so I could fire blanks.”

Behind the camera, Topper ran into some luck with his college recruits, Erik Daarstad and John Arthur Morrill, who ran the camera. Not only was the film competently shot but it has an assuredness in a lot of the set-ups, always sticking something in the foreground to offset the action in the rear, low angles, and a keen instinct for filling the frame to help keep the viewer invested. This thing just reeks of verisimilitude.

Daarstad would go on to quite the career in documentary filmmaking, and Morrill would split time between shooting for Topper and Clarke on The Hideous Sun Demon. Morrill would also go on to have quite the career in offbeat and cult cinema, lensing things like The Brotherhood of Satan (1971) and A Boy and His Dog (1975), both visually striking, and the glorious all-out dreck like Truck Stop Women (1974) and Kingdom of the Spiders (1977)

Art director Richard Cassarino would also split time between this production and The Hideous Sun Demon, and would later go on to create the amphibian monster for the totally bonkers Destination Inner Space (1966). Editor Marvin Walowitz would shift to sound design with Night Tide (1961), and would go on to work on things ranging from Tron (1982) to Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989).

Somewhat unjustly, Joyce King failed to make the credits. “My name should’ve been on that film,” King confessed to Albright. “I was at that time called a script supervisor. Then [the union] springs on me that you have to have 90-paid shooting days as a script supervisor, somebody hires you and pays you, and that was totally insane. All the time I was working under those conditions, I only got 13-days. It devastated me.”

But King would persevere and would continue working as a credited script supervisor, working with Ted V. Mikels on The Black Klansmen (1966), Tom Laughlin on The Born Losers (1967), Peter Bogdanovich on Targets (1968), and helped keep everyone on the same page for Easy Rider (1968) -- plus a ton of other exploitation classics, ranging from Werewolves on Wheels (1971), to Coffy (1973), to Black Belt Jones (1974) and Race with the Devil (1976). King would even dabble in some stunt work, anything to help the picture get done.

“It’s like working in the theater,” said King. “You get involved. You’re doing a show, and when somebody needs something, you get it. I think I wasn’t called upon, but I volunteered most of the time.” And on a follow-up feature for Topper, No Place to Land (1958), “I ended up a stunt double for Mari Blanchard in a 1918 biplane. I think that’s above and beyond the call of duty. I got out of the plane, and my legs were rubbery because the pilot had done it all. When I was able to walk, I turned the corner and literally bounced off the chest of this very big man, who happened to be the SAG representative, who asked, ‘Was that you up there?’ I was terrified. I was just beginning to hear about crap that unions can and will do to you. But they let me stay. It was probably Burt himself who paid whatever fine there was for letting a non-union person fly as a double.”

And in a later feature, The Road Hustlers (1968), King said, “Don’t laugh, but I did it again!” Only this time, it was a lot more harrowing. It was an aquatic chase scene that ended in a fiery explosion and, according to King, “The boat wiped out at 75-miles per hour, and (actor) Robert Dix dove in off the second story of the chase boat and pulled me out.” As to why she did it in the first place:

“Well, I don’t know if this sounds stupid, but after you’ve been working on a sequence and the schedule says you’re supposed to do this and this and this, and you’re coming on the 20th hour and there’s nobody there do do it, somebody always says, ‘Okay, I’ll do it.’ Unfortunately, I was that stupid person.” Somewhat ironically, Dix would go on to strangle and “murder” King when she subbed in again for a reluctant ingenue, who refused to get into the icy cold water in Blood of Dracula’s Castle (1969).

Fortunately for King, with all that dynamite and homemade squibs involved, there were no female characters for her to double in The Ground They Walk. The majority of the cast were recruited from Topper’s theater acquaintances, and running through the cast this would prove to be the one and only feature most would appear in.

Omaha World Herald (December 7, 1958).

Wally Campo was spotted by Roger Corman in a small-venue revival of Night Must Fall and recruited him into his unofficial stock company. He appeared in Corman’s Machine Gun Kelly (1958), and would go on to star in a bunch of films for the producer -- Beast from Haunted Cave (1959), Ski Troop Attack (1960), and served as the narrator on The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). And for American International, he starred in Master of the World (1961), Tales of Terror (1962) and The Devil's Angels (1967). And he would go on to appear in nearly all of Topper’s subsequent films, too.

Campo carries this picture as Russo, the squad’s bearded malcontent. His fear in the firefight feels genuine, as it did when he realizes he’s blundered into the minefield. And I liked how his hot-tempered character holds his own with the conniving German officer. That moment when he blew the canteen out of the hand of that smug asshole had me cheering.

Thus, Brandon Carroll does equally well as the venomous Schlechter. This would be Carroll’s first feature, and he would go on to have small supporting roles in the Monte Hellman westerns, The Shooting (1966) and Ride the Whirlwind (1966). Everyone else -- Fred Gavlin (Clemens), Gregg Stewart (Nelson), and Leon Schrier (Roth) -- are fine and do their best to compensate over the limitations of Topper’s script.

Said script is a little light on details and serves as the barest of threads to string together the action set-pieces. It does tend to grind up in its own gears a bit when it starts dwelling on the “horrors of war” and the effect it has on those who fight in it -- like Nelson's Battle Fatigue, where he can’t bring himself to shoot the enemy anymore because it's gotten "too easy" to kill, or while exploring Lippy’s family tree. Luckily, Topper makes the right decision and doesn’t linger on this type of navel-gazing for very long. He also injects quite a bit of humor to help grease the plot along.

There’s a pretty great running gag on how Russo is constantly foiled in his eternal quest to find a match to light his masticated cigar, and his constant failure to get Clemens to surrender his last one. But the best bit happens earlier in the film, when Nelson has to relieve himself and tears out the page of a magazine to wipe with, and the resulting horror when Russo realizes, in his haste, he tore out the coveted centerfold, which is now, well, soiled beyond recovery.

After spending six months in the desert, and then cobbling things together in the editing room, where they also added in some effective stock musical cues, his end results proved solid enough that Topper was able to sell They Ground They Walk to American International Pictures.

Buffalo Courier Express (October 10, 1958).

As usual, it was the brass at AIP, James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff, who would rebrand the film as the more exploitable Hell Squad (1958) before sending it on a double-bill in July, 1958, with Sherman A. Rose’s Tank Battalion (1958) -- with each brandishing some outstanding poster art that slightly embellished what actually happens on screen. (Hell Squad also had an ear-popping radio spot, something else that’s sorely missing these days in terms of ballyhoo, which I have an audio clip off -- but do you think I can find it now?!?)

“Those were incredibly rewarding -- and hectic -- times,” said Arkoff (Flying Through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants, 1992). “Fortunately, we had a young staff so enthusiastic about what we were doing that they were willing to work long hours. Burt Topper could do just about anything behind the scenes -- take apart a camera, build a camera mount, or produce, write, and direct a picture like Hell Squad, which was made for $20,000.”

James H. Nicholson (seated) and Samuel Z. Arkoff.

It’s unclear how much AIP paid for Hell Squad, but what is certain is that it cost way less than $20,000 to produce. As Topper confessed to Weaver, “For years and years I never did tell Sam how much the picture cost, because I didn't want him to get angry that it was so little. It cost so little, it was ridiculous. The whole damn picture cost me $11,500. Just for the television rights, I got more than that!”

Upon the (extremely) low-budget film’s release, it even managed to earn some fairly positive reviews -- and no one seemed more surprised by this than the critics themselves.

Terre Haute Tribune (November 21, 1958).

Said Lowell Redelings (Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, October 23, 1958), “Burt Topper wrote, produced and directed Hell Squad, a rather good achievement in its particular category. (Wally) Campo, wearing a beard, is the standout performer; his personal duel of wits with a German officer amid a mine field is extremely suspenseful.”

“Hell Squad is another tale of World War II, set against a desert background,” said an anonymous critic for the Los Angeles Daily News (October 11, 1958). “For a picture with an unknown cast and low budget, this is a valiant try and a fair effort.”

The Boston Globe (September 1, 1958).

Also chiming in was the Terre Haute Tribune (November 21, 1958), who reported, “Hell Squad bears the indelible stamp of one man. He is young Burt Topper, who wrote, produced and directed. His achievement is hailed as one of the outstanding single efforts in recent years. And the consensus of opinion of professional motion picture makers privileged to see an advance screening of Hell Squad is that it is the work of a man destined for greatness in Hollywood.”

Said The Brownsville Herald (October 12, 1958), “Hell Squad is a violent telling of the terrible war experiences of eight [sic] American G.I.s cut off from their command post in the Libyan [sic] desert campaign against the Germans in World War II. It boasts authenticity seldom found in war films, and because of its realness it is not for the squeamish.” (Full disclosure, this sounds an awful lot like a simple regurgitation of a studio press release to me.)

According to the Boston Globe (September 13, 1958), "Hell Squad is probably as accurate an account of real warfare as a group of Little Theater graduates can make it. Unpretentious but graphic in its description of World War II, the soldiers are rough, bearded and dirty and not the clean-shaven heroes that are too often seen in pictures describing war adventures. The action is tough and bloody. It’s kill or be killed in this forceful story of how five American G.I.s escape their captors.”

And in rebuttal, we have Ray Lowery (News and Observer, October 29, 1958), “The oft-told adventures of an American patrol lost behind enemy lines gets a replay here for minor reaction in this modest budget entry. The all-male cast of comparative unknowns struggle with the material and [the] direction of Burt Topper, who follows familiar dramatics in the desert setting, with extended periods of dialogue interspersed with several brushes with enemy scouting parties.”

Considering its budget, it should come as no surprise that Hell Squad went on to make a considerable profit for American International. And as catch-all producers and directors like Alex Gordon (-- Girls in Prison (1956), The She Creature (1956), Dragstrip Girl (1957), Herman Cohen (-- I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), Blood of Dracula (1957), How to Make a Monster (1958), and Bert I. Gordon (-- The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), The Spider (alias, Earth vs the Spider, 1958), Attack of the Puppet People (1958), left AIP over financial disputes, Arkoff quickly signed Topper to a multi-picture deal in October of 1958 to shore things up.

According to the Los Angeles Times (October 17, 1958), on Topper’s slate were four films for the studio, including Tank Destroyers, Young Warrior, Last Woman on Earth, and Yacht Party. It’s unclear whatever became of Young Warrior or Yacht Party, which most likely died on the vine. And Last Woman on Earth (1960) wound up being made by Roger Corman and was released by Filmgroup.

As for Tank Destroyers, that one did get made by Topper but was released as Tank Commandos (1959) on a double-bill with Operation Dames (1959), as part of AIP’s brief but glorious glut of low-budget war pictures (-- which we’ll get to in a second). Topper would also make Diary of a High School Bride (1959), which he reportedly shot in seven days on an exorbitant budget, at least for him, of $80,000, before parting ways with the studio and once more striking out on his own.

He would make the aforementioned War is Hell for Allied Artists, and then really moved the needle with the release of The Strangler (1964), a sleazy psychological thriller, which sees a man (Victor Buono) with severe mommy issues and a doll fetish turn serial killer, who then murders his way through a series of nurses.

Here, like Corman before him, Topper’s brand of blunt, straightforward storytelling, with sudden explosions of graphic violence, with an undercurrent of social commentary brewing underneath, soon had the European critics taking notice of his work in publications like Cahiers du Cinema, who labeled him as one of the new breed of cinematic auteurs like Corman and Budd Boetticher.

But Topper never really cashed in on this sudden surge of notoriety and instead went back to work for Arkoff and AIP, who were going through a slight regime change after Nicholson’s divorce left him a minority shareholder -- we took a deep dive on this schism in our review of Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1966).

The Grand Island Independent (June 22, 1967).

Here, Topper was put in charge of physical production, serving as an executive producer on Fireball 500 (1966), Devil’s Angels (1967), The Devil’s 8 (1969) and The Hard Ride (1971). After, he would once again strike out on his own, finishing his career with the offbeat Soul Hustler (alias The Day the Lord Got Busted (1973), where Fabian Forte plays a dope-smoking evangelist, and a juvenile romp about a robot dog crimebuster called C.H.O.M.P.S. (1979).

In his post memorializing Topper, who passed away in 2007, Weaver confirmed what I had been saying for years when it came to these types of films and productions. Said Weaver, “I didn't say this to Topper [during our interviews] but I sure was thinking, as he was telling his stories -- electrocuting crabs, watching rushes where all you see is the cameraman's face because he held the camera backwards, having an actor running around like a maniac amidst a real-life forest fire -- that this stuff was a heckuva lot funnier and more colorful than the incidents depicted in Ed Wood (1994),” which was Tim Burton’s delightful biopic on the alleged worst filmmaker in the world.

Yeah, as you dig into these films, more often than not their production stories prove just as -- and in most cases, even more -- entertaining than the films themselves. And a huge tip of the hat to the likes of Weaver and Albright who managed to get these stories on record before it was too late, as the majority of those who made these films are sadly no longer with us.

As a case in point, King left this after-action report on the production of Tank Commandos. “We were out in Pomona, and guys in German uniforms and black boots and helmets came up out of the sewer. The town went wild! They called the FBI, and it was traumatic for everyone. But visualize a sewer pipe with a diameter of, say, 12-feet, and that’s where we worked. What was I doing down there? I was trying to do my job.” Then, “Topper said, ‘We’re out of money, we’re out of food, and you’ve got to do something.’” And so, “I went to the Pomona Fairgrounds, where my adopted aunt gave me $50. I went back and got hamburgers for everybody. We finished the day, but we were out of money and out of gas and out of everything.”

Hell Squad is easily the best of American International’s brief slate of war pictures. They tried hard, but most bit off a little more than they could chew. Tank Battalion could only muster one tank, and Submarine Seahawk (1958) literally drowns in (easily identifiable) stock footage. Jet Attack (1958) and Suicide Battalion (1958) were serviceable but fairly rote. And Operation Dames was kinda fun, but couldn’t quite decide if it was a comedy or not.

No, the only picture that comes even close to matching the quality and intensity of Hell Squad is William Witney’s Paratroop Command (1959), which does a commendable job on its budget, too, spinning its tale of paranoia and mistrust after a case of dubious friendly fire -- anchored superbly by a cast of Richard Bakaylan, Jack Hogan and Jeff Morris.

“It contains a realism that sets it apart from most other WW2 movies done in that same era,” said Quentin Tarantino of Paratroop Command (Letteboxd, April 6, 2020). “So much so that it makes a lot of good and similar movies from that same time, Robert Aldrich’s Attack (1956) and Don Siegel’s Hell is for Heroes (1962), look theatrical and stagey by comparison.”

The same could be said of Hell Squad. And while Hell Squad does fall victim to all the sins of its low-budget brethren, again, it manages to overachieve and engages its audience on a fundamental level. You feel the heat and can smell the sweat dripping off of everyone. And during its beats of high suspense, it really rubs your nose in the dirt the characters are scrabbling around in, too, thematically speaking. And I admire their effort to show more than they tell -- the bane of any low-budget film no matter what the genre.

And that’s what I find truly amazing and enjoy so much with films created in this low-budget strata, where, despite the lack of money, surviving all the trials and tribulations of just getting footage in the can, let alone making something worth distributing, can turn out something good -- not so bad it’s good, mind you, and not only watchable, but engaging. It's raw, it's rough, and it's ready to go.

Thus, despite all of its shortcomings, Hell Squad still manages to notch a spot in the conversation when discussing my favorite war films. It's by no means great, but it is pretty good. Honest. And its effective minimalism bears some befuddling yet effectively real results given the destitute circumstances in which it was bred. Topper might not have been an auteur, but he sure could spin one helluva yarn.

Originally posted on February 6, 2024 at Confirmed Alan_01.

Hell Squad (1958) Rhonda Productions :: American International Pictures / P: Burt Topper / D: Burt Topper / W: Burt Topper / C: Erik Daarstad, John Arthur Morrill / E: Marvin Walowitz / M: Jay B. Richardson / S: Wally Campo, Brandon Carroll, Fred Gavlin, Gregg Stewart, Leon Schrier, Cecil Addis, Jack B. Soward

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment