"It has to kill us or starve, and we've got to kill it or die."

With a slow track over the rocky and desolate surface of Mars our latest epic begins, augmented by a solemn prologue from Colonel Ed Carruthers, who waxes on and on about this hellish landscape seen before us, until the camera eventually settles on the wreckage of the Challenge-141 starship, which cracked-up while attempting the first ever manned-landing on the Angry Red Planet.

The lone survivor out of a crew of nine from this ill-fated vessel, Carruthers (Thompson) also warns it wasn't the crash that killed the others but some kind of horrible monster (-- cue ominous musical sting), who picked his shipmates off, one by one, and violently shredded them. Here, our movie proper begins with the impending departure of the rescue ship, the aptly named Challenge-142.

Under the command of Colonel Van Heusen (Spalding), he, along with the rest of the 142's crew, doesn't buy the castaway’s incredible story. In fact, they all believe it was Carruthers who killed the crew of the 141 to hoard and stretch-out the meager rations while waiting-out a rescue ship. Thus, despite these protests of innocence, Heusen intends to extract Carruthers' full confession before they reach Earth, where a general court-martial and summary execution awaits on multiple counts of murder.

However, as the final countdown to the launch commences, Heusen is alerted that one of the lower-level cargo hatches is still open. Somewhere below, Lt. Calder (Langton) apologizes, having accidentally left it ajar after dumping some garbage over the side to lighten the load for the trip home; but as he closes the hatch, the camera tracks away, revealing the shadow of something monstrous lurking in the back of the hold.

Then, the sparklers are lit -- sorry, the fuel is ignited, and the Challenge-142 slowly rockets back to Earth, her crew blissfully unaware they’ve picked up an unwanted stowaway -- a stowaway that's both vicious and very, very hungry…

Now, class, here we have the cinematic poster child on the dire consequences of littering on a galactic scale. Seriously, though, IT! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958) is a bona fide classic and a seminal film, which spawned and inspired plenty of features that followed in its wake -- some more obviously than others. And we're going to get to all that, but first, we're gonna take a look at, and once again debate over, what arguably helped inspire those who inspired in the first place.

Starting in July, 1939, Astounding Science Fiction magazine, one of the premiere Sci-Fi pulps of the era (-- of any era, really), published a series of short stories by author A. E. van Vogt concerning the exploits of The Space Beagle: a massive, manned interstellar exploratory vessel, whose own impact and influence on the Science Fiction genre are arguably still rippling through all stages of every medium to this very day.

A.E. van Vogt

Born Alfred Vogt on April 26, 1912, in the small Mennonite community of Edenburg, Manitoba, Vogt spent most of his youth moving around Canada as his father shifted jobs. He started writing in his late teens while working in advertising, selling a few “True Confession” type stories to the local paper and a few national magazines along with several short radio dramas.

By 1938, he switched to writing Science Fiction after picking up an issue of John W. Campbell’s Astounding, which featured Campbell’s own seminal story, Who Goes There? (Astounding, August, 1938) -- later adapted into The Thing from Another World (1951), and then remade later as The Thing (1982). And it was this tale that inspired Vogt to write Vault of the Beast, who then submitted it to the magazine, which netted him a rejection letter from Campbell himself.

But! That very same rejection letter also encouraged the fledgling author to try again. And try again Vogt did, adding an “E” (for Elton) and a “van” to punch up his author credit for Black Destroyer (Astounding, July, 1939), launching one of the most, sadly, maligned and unjustly unheralded runs in the Science Fiction genre.

"The son-of-a-gun gets hold of you in the first paragraph,” said Campbell (The John W. Campbell Letters, 1985). “Ties a knot around you, and keeps it tied in every paragraph thereafter -- including the ultimate last one.” And Campbell wasn’t alone with praise for Vogt.

When asked which writers had influenced his work the most, author Philip K. Dick said (Vertex, February, 1974), “I started reading Science Fiction when I was about twelve and I read all I could, so any author who was writing about that time I read. But there's no doubt who got me off originally and that was A. E. van Vogt.

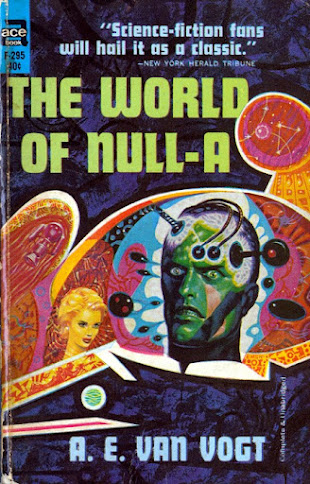

“There was in Vogt's writing a mysterious quality, and this was especially true in The World of Null-A. All the parts of that book did not add up; all the ingredients did not make a coherency. Now some people are put off by that. They think that's sloppy and wrong, but the thing that fascinated me so much was that this resembled reality more than anybody else's writing inside or outside Science Fiction."

Harlan Ellison, a longtime Vogt defender and champion, added in Harold Drake’s The Null-A Worlds of A.E. van Vogt (1989), “Vogt was the first writer to shine light on the restricted ways in which I had been taught to view the universe and the human condition." But David Hartwell probably summed it up best in his book, Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction (1984):

“No one has taken Vogt seriously as a writer for a long time. Yet he has been read and still is. What no one seems to have noticed is that Vogt, more than any other single Science Fiction writer, is the conduit through which the energy of Gernsbackian (Amazing Stories), primitive wonder stories have been transmitted through the Campbellian age (Astounding), when earlier styles of Science Fiction were otherwise rejected, and on into Science Fiction of the present."

What Hartwell means, I think, is to some Vogt deftly bridged the gap between the fantastical, gee-whizbang age of Science Fiction, which relied more on fiction than science, and the epoch Campbell revolution, which required a fiction more grounded in a basis of science and facts.

Others disagreed. Most notably fellow author and critic, Damon Knight, who took the “Cosmic Jerrybuilder” to task in an essay for the fanzine Destiny’s Child (November, 1945), where Knight adamantly felt Vogt was “no giant” but a “pygmy [that] has learned to operate an overgrown typewriter,” who failed consistently as a writer because, one, “His plots do not bear examination;” and two, “His choice of words and his sentence-structure are fumbling and insensitive;” and three, “He is unable either to visualize a scene or to make a character seem real.”

Fellow Sci-Fi writer Robert Silverberg felt the same way but not quite as harshly, saying Vogt’s writing style was the “purest gibberish to [his] adolescent mind. Lively gibberish, yes, but gibberish all the same.” He then summed up Vogt’s overall and somewhat juvenile approach -- that always sends the Blue Noses into a tailspin tizzy -- rather succinctly when discussing The World of Null-A (Rereading Van Vogt, 2009): “The book seems to be a goofy masterpiece with no internal logic of plot or character, a kind of hallucinatory fever-dream that carries the reader along on a pleasant tide of bafflement.”

In that same Vertex interview, Dick would defend Vogt against Knight’s acidic assertions, saying, “Damon feels that it's bad artistry when you build those funky universes where people fall through the floor. It's like he's viewing a story the way a building inspector would when he's building your house. But reality really is a mess, and yet it's exciting. The basic thing is, How frightened are you of chaos? And how happy are you with order? Vogt influenced me so much because he made me appreciate a mysterious chaotic quality in the universe which is not to be feared.”

Unfortunately, the damage was done and that long running feud with Knight, along with some ardent political views in his writings that favored the Übermensch and benevolent dictatorships, damaged Vogt’s reputation over the years.

Not helping matters further was his association with L. Ron Hubbard, who lured Vogt in with his theories on Dianetics in 1945. Vogt was then appointed the head of Hubbard’s Dianetics self-help operation in California in 1950, which went broke nine months later but was saved from bankruptcy when the author buoyed the finances with his own money. All the while his typewriter remained silent until he checked-out in 1961, when Hubbard’s Church of Scientology started picking up steam -- something Vogt never approved of, feeling it was a load of hokum.

I, myself, am a huge fan of the author, whom I discovered back in high school in the mid-1980s, which led me to his yarn, Black Destroyer, where the bickering and battling crew of the Beagle find a large, tentacled, lion-like creature amongst the ruins of an ancient alien civilization.

Taking this new specimen on board the ship for further study, though friendly at first, the “Coeurl” quickly shows its true stripes and starts killing the crew; first clandestinely, and then overtly, sucking the potassium it needs to survive (known natively as id) from the corpses:

“Coeurl reached out and struck a single crushing blow at the shimmering transparent headpiece of the spacesuit. There was a tearing sound of metal and a gushing of blood. The man doubled up as if part of him had been telescoped. For a moment, his bones and legs and muscles combined miraculously to keep him standing. Then he crumpled with a metallic clank of his space armor. Fear completely evaporated, Coeurl leaped out of hiding. With ravenous speed, he smashed the metal and the body within it to bits. Great chunks of metal, torn piecemeal from the suit, sprayed the ground. Bones cracked. Flesh crunched. It was simple to tune in on the vibrations of the id, and to create the violent chemical disorganization that freed it from the crushed bone. The id was, Coeurl discovered, mostly in the bone.”

Every attempt to kill the rampaging beast fails, as all their interior weapons prove useless, until the creature is tricked into a escape-pod, jettisoned, and then suicides out rather than face the Beagle's larger atomic-disintegrator cannons.

In the follow up story, Discord in Scarlet (Astounding, December, 1939), the Beagle runs afoul of another ancient alien: the Ixtl (alias the Xtl), a vicious insect-like creature that had been free-floating in the vacuum of space since before the Big Bang. Once brought on board, the creature revives and escapes. Then, while hiding in the ship's air-shafts, the Ixtl abducts several crew members, who serve as hosts when the beast implants its parasitic eggs inside them:

“Morton watched the skillful fingers of the surgeon, as the electrified knife cut into the fourth man’s stomach. The last egg was deposited in the bottom of the tall neutronium alloy vat. The eggs were round, grayish objects, one of them slightly cracked. As they watched, the crack widened; an ugly, round, scarlet head with tiny, beady eyes and a tiny slit of a mouth poked out. The head twisted on its short neck, and the eyes glittered up at them with a hard ferocity. And then, with a swiftness that almost took them by surprise, it reared up and tried to run out of the vat, slid back -- and dissolved into the flame that Morton poured down upon it.”

Able to phase through solid objects, and possessing great stealth and speed -- so much so all the surviving witnesses can recall is "a scarlet blur" -- the ghostly creature continues to buzzsaw through and impregnates a good chunk of the crew until they trick the alien into vacating the ship, which then warps away, leaving the monster stranded in the void of deep space once again.

Two other episodes would follow -- M33 Andromeda (Astounding, August, 1943), where the Beagle must lead a nebulous, planet destroying vapor on a wild goose-chase until it starves to death, and War of Nerves (Other Worlds, May, 1950), where they meet some benevolent bird-like aliens called the Riim but are hampered by a deadly language barrier.

These last two installments introduced the character of Dr. Elliot Grosvenor, an expert in Nexialism -- an uncanny integration of science and thought in terms of conflict resolution, whose roots are probably found in Hubbard’s Dianetics, where a person can see the connections between different disciplines and unite them in service of the common good.

All four tales were eventually collected into a novel, The Voyage of the Space Beagle (1950) -- the starship named after Charles Darwin’s own vessel of discovery, where the first two installments were extensively rewritten to insert Grosvenor as the main protagonist throughout plus additional material to string the four tales together. The book was later reprinted as Mission: Interplanetary, where I first encountered them. And even if you're just a casual genre fan, you owe it to yourself to track these tales down and give them a read. And if those stories sound or ring familiar to you, well, you're not alone.

The Grand Island Independent (July, 1979).

Over the years, many a savvy Sci-Fi fan has traced many of the themes and elements of Ridley Scott's Alien (1979) back to IT! The Terror from Beyond Space; both claustrophobic tales of a small crew trapped on a spaceship, facing an indestructible creature that randomly picks them off and violently dispatches them -- one in the interest of reproduction, the other more of a culinary enterprise. But I, like many others, didn't think they looked back far enough.

In 1979, Cinefantastique magazine ran an article comparing the two films, along with a third, Mario Bava's Planet of the Vampires (alias Terrore nello Spazio,1965). Had Alien screenwriters Dan O'Bannon and Ronald Shusett seen these films? Or read Vogt’s stories? And did it help influence their screenplay? Maybe. Maybe not. But probably.

“I didn’t steal from anybody,” said O’Bannon. “I stole from everybody.” In the Alexandre Philippe documentary, Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019), they do a deep dive into O’Bannon’s myriad influences, which initially stemmed from a phobia of insects and a morbid fascination with the life-cycle of the cicada.

On the cinematic front, they cite both IT! The Terror from Beyond Space and Planet of the Vampires plus a couple others, including Curtis Harrington’s Queen of Blood (1966), which focuses on another alien hitchhiker, feeding off the blood of the male crew, facing off against a female protagonist that ends with the entire ship infested with gelatinous alien eggs, ready to hatch and conquer once they reach Earth.

They also cite two comic book tales. First was "Seeds of Jupiter" (Weird Science, No.8, July, 1951), which sees a Navy seaman accidentally swallowing a “peach-pit from outer space.” Only it was a different kind of seed -- a parasitic alien seed, which leads to a rather gruesome panel where a squid-like monster splurts from the patient’s stomach while on the operating table. Written and illustrated by EC Comics legends Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein, the alien squid soon grows to kaiju-size and attempts to conquer the world.

Now, the second illustrated tale is the highly disturbing "Defiled" (Death Rattle, No.1, June, 1972), whose skybox screamed, “Violated! Raped! No courtship, love or gentle foreplay. A brutal attack with sexual organs incompatible with the human form. Tearing, piercing, crushing! After such an assault death would be a blessing, but even this is denied! There is no peace for -- The Defiled!”

"Seeds of Jupiter" (Weird Science, July, 1951)

"Defiled" (Death Rattle, June, 1972).

Here, author and artist Tim Boxell strikes a rather nauseous and an extremely graphic chord as an unwitting salvage agent is blinded, raped and impregnated by a malevolent alien force, whose gestating progeny takes control and slowly consumes the well-aware host body from the inside out, sending it on a forced march to find proper hatching grounds, where it eventually uses him as live bait to lure in more “incubators.”

On the literary front, Vogt’s The Voyage of the Space Beagle barely gets a drive-by, a blink and you’ll miss it blip, listed on a typed piece of paper. (At least it was on the top of the list.) Instead, the documentary focuses on the more well known tale of H.P. Lovecraft, At the Mountain of Madness (Astounding Stories, February - April, 1936), where an ancient alien civilization is found buried under the Antarctic ice, constructed by the not-quite as extinct as they thought “Elder Things,” who rise and commence to slaughtering the expedition. And we haven’t even gotten to the ‘Evil that Lives Below All’ one mountain over.

To me, this slight to Vogt’s work was a tad disingenuous in an otherwise excellent and exhaustive origin story on the confluence of influences that led to Alien. Unfortunately, when people use the word "influence" when talking about popular media these days it often has a negative connotation. Why say “influenced” or “inspired” when what you really meant to say was “ripped off.” And to confuse things even further, I'm not really sure where the line is when it stops being a ‘rip-off’ and becomes a ‘homage.’

But just as George Lucas was inspired by the likes of Alex Raymond, matinee serials, and Akira Kurosawa for Star Wars (1977), O'Bannon, just coming off of Dark Star (1974) and Alejandro Jodorowsky's aborted attempt at adapting Frank Herbert’s Dune, cherry-picked several key elements from varied sources, put them in a blender, added his own take, and ended up with one of the scariest movies ever made.

And isn't that what the creative process is? Taking what you've experienced, seen and heard, and make them your own? We'll give that a qualified "yes" -- as long as you're not too obvious about it, or you at least cite your sources and, where applicable, compensate them.

Frankly, I see more of Vogt's Discord in Scarlet in Alien than anything else. And so did the author, whose plagiarism case was strong enough 20th Century Fox quickly settled out of court for $50,000. Vogt probably would’ve had a strong case against producer Robert E. Kent, his Vogue Pictures, and United Artists back in 1958, too, since Jerome Bixby’s script for IT! The Terror Beyond Space hews pretty close to Black Destroyer, and we’ll be discussing that further in just a bit.

But

for now, let's catch back up with the crew of the Challenge-142, their

prisoner, and the unwanted stowaway, as they leave Mars behind and begin

the long, four-month trek back to Earth.

Here, Carruthers continues to plead his innocence, still insisting a malevolent Martian monster killed his comrades until Heusen shows his prisoner some of the remains they’d recovered, revealing one of the skulls has a bullet hole in it. And since there is only one kind of "monster" in this universe who uses bullets, this clinches the man's guilt as far as Heusen's concerned -- despite Carruthers insistence the shooting was an accident and the victim was already dead when the errant bullet struck. But Heusen will not listen and the rest of the crew pretty much feels the same way.

Speaking of the crew, they are a standard representation of 1950s-era space-pioneers (-- and every last one of them a chain-smoker). Calder is from Texas; and then we have Gino and Bob Finelli, the requisite brothers from Brooklyn (Harvey, Benedict); also along on this ride is the ship's physician, Dr. Mary Royce (Doran), and her husband, Eric Royce (Greer); and of course, the obligatory love interest, biologist Ann Anderson (Patterson) -- and does anyone else find it funny they made the ship's medical doctor and biologist women, yet they're still in charge of making dinner, serving coffee, and doing the dishes! (Good grief.)

There're a couple more "Red Shirts" at the bottom of the cast list; and since we know they’re probably toast, we’ll just introduce these poor souls as they’re knocked off. Starting right about now, when some strange noises from the allegedly empty lower decks draw Keinholz (Carrey) down to the darkened cargo hold to investigate.

Now, one should probably note the layout of the Challenge-142 rocket is vertical -- like a lighthouse: five decks in all, with one central stairway and a sealable hatch on each floor. And after a few suspenseful turns, Keinholz gets attacked by the savage stowaway.

Of course, only Carruthers hears something odd, his senses keenly attuned after “relearning how to hear” after his time on Mars; and fearing what it could be, demands that the others investigate.

Splitting up to search the ship, Gino Finelli makes a bee-line for a vital storage bin first: the one with all the cigarettes stored in it! But before he can even light-up, the monster lunges from out of nowhere and attacks.

Now with two crew members missing, as the search expands, they finally find Keinholz's pulverized and exsanguinated body stuffed-up in an air vent. Volunteering to search the air-shafts further, Major Purdue (Bice), our second Red-Shirt, finds Gino, who's barely alive. Unfortunately, he also finds the monster. But! Purdue does manage to scramble away and escape, but not before the taloned terror tears up his face.

Proven right, this vindication means little to Carruthers with all of their lives now in mortal danger. And knowing what they face, he quickly instructs the others to barricade the air-vents and then helps to rig-up an explosive trap for the monster.

But when the expended grenades don’t even slow it down, the scrambling crew members try some gas bombs Gino had cooked up in case they ran into some dinosaurs on Mars. (Remember, this is the 1950s, and new planets were either inhabited by Iguana-shaped dinosaurs and dorsal fin-decked-out caimans that fought to the death or tribes of buxom Amazonian women. Sometimes both.) With gas masks donned, the crew bombards the creature below; but this tactic doesn't work either and Heusen is severely mauled in the resulting mêlée.

Forced to retreat up another deck (-- and there ain't that many left, he typed ominously), Royce concocts a plan to electrocute the invader. Here, Carruthers and Calder don their space-suits and use the airlocks to go outside the ship and circle down below the monster, where they connect a high voltage wire to the central stairway. But when it gets the juice, sticking with the established pattern, this has no visible effect on the monster -- except pissing it off.

Thus, Carruthers barely makes it back to the airlock but Calder wasn't so lucky. He takes a beating, gets his leg broken, and, worse yet, the monster cracks the face-plate on his suit -- so he couldn’t escape out the airlock even if he could get to it. And so, after squeezing himself into a corner, Calder uses a handy acetylene torch to hold the creature off and orders Carruthers to go on without him and get help.

Meanwhile, as Carruthers slowly makes his way back up the side of the ship, Dr. Royce finishes her autopsy on Keinholz, where she discovers the victim died of acute dehydration -- not the severe beating, most of which was done postmortem. Somehow, she says, the monster sucked all the oxygen, blood, and water, every ounce of liquid, from the body through some kind of osmosis. Dr. Royce also warns the wounded are infected with some kind of alien bacteria and without more whole blood, they will surely die.

Of course, the way this trip's been going, all the needed medical supplies are right where the monster currently is. Still kicking below, Calder radios a report that the monster has taken Gino's corpse and moved into the reactor room. Seizing the chance, the others remotely seal the thing inside the lead-lined chamber. Once that is done, Carruthers, Bob Finelli, and Royce head down to retrieve Calder and the needed medical supplies.

But while they're gone, in a bacterial-charged delirium, Heusen opens the reactor core, exposing the monster to a massive dose of radiation in another attempt to kill it. Alas, and again, this only makes the monster even more mad; and after tearing through the reactor door like it was wet tissue paper, the Martian proceeds to rip Finelli apart before he can rescue Calder.

But with the monster gruesomely distracted, Carruthers and Royce retreat with the medical supplies while Calder, left behind again, resumes fighting off the monster with his torch.

Unable to get at this prey, the frustrated beast flies into another frenzy and starts busting its way up through the sealed decks to get at the others, who’ve retreated all the way to the command deck -- the upper-most level of the ship.

With nowhere left to run, as the few survivors prepare for a final stand, Carruthers notices some peculiar readings on the ship’s oxygen levels. They’re way down, meaning consumption levels are way up. Way, way up.

Here, Royce deduces the monster must be the cause, and they hit upon a plan to shut the air off and blow the airlock, which should suffocate the creature and finally end its reign of terror. Radioing their intentions to Calder, he manages to seal himself safely in the lower airlock. Up above, while the others frantically don their space suits, the monster claws its way through the last hatch, cutting Carruthers off from the airlock controls.

But as Royce bounces a few bazooka shells off the creature's head, Heusen nobly sacrifices himself, lunging on top of the creature to get at the switches while Carruthers distracts it and blows the hatch. With that, the resulting explosive decompression asphyxiates the creature and it finally dies.

Back on Earth, the head of the Science Advisory Division of Interplanetary Exploration solemnly reads a tele-radio message from what's left of the crews of the Challenge-141 and 142 to the gathered media:

“Of the nineteen men and women who have set foot on the planet Mars, six will return. There is no longer a question of murder, but of an alien and elemental life-force. A planet so cruel, so hostile, that man may find it necessary to bypass it in his endeavor to explore and understand the universe. Another name for Mars … is Death."

After selling his first script back in 1937 -- an early vehicle for Rita Hayworth called Paid to Dance (1937), Robert E. Kent never looked back, cinematically speaking. And not one to limit himself, over the next three decades, and under countless pseudonyms, the screenwriter brazenly dabbled in all genres with a prolific, speedy, and solid reputation soon established.

Thus, Kent was always in demand, mostly for second features and serials; but his career really took shape in the 1950s when he hooked onto producer Sam Katzman's cheap-jack Four-Leaf circus wagon at Columbia, penning several of William Castle's pre-gimmick historical “epics” -- Serpent of the Nile (1953), Fort Ti (1953), Siren of Baghdad (1953), and the totally under-appreciated shocker, The Werewolf (1956), for Fred Sears.

All the while watching and learning how to maximize profits by minimizing costs behind the camera as he pounded out script pages, it wasn't long before Kent decided to expand his film horizons well beyond a typewriter. And in 1957, he started producing his own independent features under several different banners -- Peerless Productions, Vogue Pictures, Premium Pictures, and Zenith Pictures, striking a deal with Edward Small at United Artists for the eventual distribution of Gun Duel at Durango (1957) and Chicago Confidential (1957), which would payoff even further.

As Philip K. Scheuer wrote (The Los Angeles Times, November 21, 1957), “Edward Small’s ‘58 schedule calls for the making of eight features -- a most respectable slate for these parlous times. Robert E. Kent, Small’s favorite producer, has been signed to supervise them for filming under the two subsidiary banners of Peerless and Vogue. Sample titles: IT -- the Vampire from Outer Space, Guns, Girls and Gangsters, The Curse of the Faceless Man, Riot in Juvenile Hall and Oklahoma Territory. Kent completed four in 1957.”

But Oklahoma Territory didn’t see a darkened theater until 1960; Riot in Juvenile Hall became Riot in Juvenile Prison before it came out in 1959 along with Guns, Girls and Gangsters. Which leaves us with the Sci-Fright twin-bill of IT -- The Vampire from Outer Space, which would also go through a last-second name change, and Curse of the Faceless Man (1958).

Seeing what the likes of American International Pictures and Allied Artists were making back on such a low investment on their genre films, this wasn't that hard a sell as Small quickly gave Kent the green-light. And to direct both pictures, Kent plucked the wily and fast-shooting Edward L. Cahn away from the ranks of American International (AIP).

Edward L. Cahn (and his ever present smoking pipe).

Cahn began as an editor at Universal, who infamously finished the final cut of Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) on the train ride to its New York premiere. He slid into the director’s chair by 1931, giving us his take on the Shoot-Out at the O.K. Corral in Law and Order (1932) and the violent pre-code crime thriller, Afraid to Talk (1932). He then migrated to MGM under a cloud of somewhat dubious circumstances by 1935, where he settled or was banished, depending on your source, into making Our Gang / Little Rascals shorts for the next decade.

But Cahn got back into features in the 1950s and was soon in demand for his ability to bring in his ‘5 to 10 Day Wonders’ both on time and under budget, starting with Creature with the Atom Brain (1955) for Katzman before becoming a mainstay at American International -- Girls in Prison (1956), The She-Creature (1956), Dragstrip Girl (1957), Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957), where Cahn did just as much as Roger Corman, Herman Cohen, and Bert I. Gordon to put the ‘Little Studio that Could’ on the map -- and Kent was hoping for more of the same from the veteran director.

Venusian Turnip (left), Paul Blaisdell (right).

To realize his monsters, for Curse of the Faceless Man, Kent turned to noted gorilla man, Charlie Gemora, who designed the aliens for Paramount’s War of the Worlds (1952) and I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). But for his deadly Martian, the producer turned to another American International alum, Paul Blaisdell, whose outlandish creature designs for The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), The Day the World Ended (1955) and It Conquered the World (1956) also helped AIP establish its memorable footprint on the 1950s.

It was while attending the New England School of Art and Design when Blaisdell met his future wife, Jackie Boyle, who would go on to be a co-conspirator on a lot of his prop designs and monster builds -- all kit-bashed together in their home workshop nestled in the hills of Topanga Canyon. But by 1958, things had soured considerably between Blaisdell and AIP co-founders, James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff.

Tired of their good cop / bad cop routine and their forgotten promises, coupled with the long hours, little pay, and less recognition for the work he was required to do on their non-existent budgets, it was really starting to grind on Blaisdell. Then, things really started to unravel when some of his prized creations were loaned out and purposefully destroyed in a fire during the climax of Cohen’s How to Make a Monster (1958) -- a somewhat prescient meta tale where a monster-maker and make-up man exacts a deadly revenge on the studio execs who fired him.

Then, as the ‘little studio’ got bigger, things became more and more regimented on the sets (-- I shudder to think of how many unions he would’ve had to join to do all of what he usually did). Blaisdell missed the family feel, the checked egos, and the "let's all pitch in" attitude from when he first started out just three short years prior. Thus, a fed-up Blaisdell’s career as a monster maker appeared to be pretty much over when Kent approached him about working on IT! the Terror from Beyond Space.

Jackie Blaisdell, Paul Blaisdell (in costume), Bob Burns.

Said Randy Palmer (Paul Blaisdell: Monster Maker, 1997), “Blaisdell’s participation hinged on the screenplay. He wanted to see it, hold it in his hands, and read it. And he wanted to get Jackie’s opinion. As the years had gone by, he had become more and more cautious about accepting jobs that required a major commitment of time and resources.” Along with the snowjobs by AIP and Corman’s Filmgroup, Blaisdell had been burnt by the Milner brothers, who bastardized his designs for the Tabanga, the galumphing sentient tree stump let loose in From Hell it Came (1957). He also got screwed over by our old friend Al Zimbalist for Monster from Green Hell (1957), who never paid Blaisdell for his giant wasp concept designs.

And so, as Palmer continued, “[Blaisdell] was determined not to be exploited by AIP or anyone else. The only way he could successfully avoid being taken advantage of, he decided, was to read a finished film script to see exactly what would be expected of him and not just assume that what the producer or director said was gospel.” Kent was happy to oblige, only there was a slight problem. The script for IT! The Terror from Beyond Space wasn’t finished yet.

Rumor has it that the makers of IT! The Terror from Beyond Space also contemplated bringing suit against the makers of Alien back in 1979, too, but that would've been a classic case of the pot calling the Coeurl a Martian. For as much as the xenomorph was inspired by the Ixtll, IT's killer creature owes a substantial debt to both Vogt's Black Destroyer and Campbell's stealthy alien from Who Goes There? -- and probably even more to its first film adaptation, The Thing from Another World.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (Clark, Peters, 1993), it concludes that Alien borrowed from IT! but “that film itself cannot claim great originality being reminiscent of Vogt’s Black Destroyer.” On the other hand, noted Sci-Fi film historian Bill Warren has done due diligence in debunking the fallacies of this ‘Fruit from the Same Tree’ theory as illogical despite all of the compelling evidence to the contrary. “There’s a logical error that too many fans make,” said Warren (Keep Watching the Skies, 1997). “Post hoc ergo propter hoc -- which I think means something like ‘If it came after, it must have been based on what came before.'”

As I noted earlier, both halves of Kent’s proposed double-feature would be scripted by noted Sci-Fi author, Jerome Bixby. Along with his writing, Bixby had served as an editor for H.L. Gold’s Galaxy Science Fiction and Thurman Scott’s Fiction House publishing, where he oversaw both pulps and comics like Jungle Stories, Planet Stories, and Action Stories; but he’s probably most famous for penning the script for Fantastic Voyage (1966), the classic Twilight Zone episode, "It's a Good Life” (Season 3, Episode 8, 1961), and several episodes of Star Trek, "Mirror, Mirror" (Season 2, Episode 4, 1967), which introduced the evil doppelgangers of the Mirror Universe, "Day of the Dove" (Season 3, Episode 7, 1968), and "Requiem for Methuselah" (Season 3, Episode 19, 1969).

In an interview with Dennis Fischer (Cinefantastique, Vol.27 No.11, 1996), who broached the subject of IT!’s influence on Alien, Bixby responded cautiously, “You have to understand that I have to be careful in answering that one. There certainly were conspicuous similarities. The creature on a spaceship sneaking people off into the ventilation systems, between the hulls, in the air ducts. Invincible. Bursts through every defense they could erect. Killing the crew members, one by one, and at the end snuffed by suffocation. I wanted the same sort of isolation situation -- a small group of people faced with something that was overwhelming them, ripping them -- [and] I thought a spaceship would be the perfect place and the perfect setting.”

Bixby admitted to Warren that he felt the biggest influence on his script was Campbell’s story -- another paranoid tale of an isolated group in Antarctica facing off against a nigh-indestructible alien threat -- with the added wrinkle of the Thing’s ability to subsume its victims, calve off, and steal their identities. Howard Hawks’ film adaptation nixed the doppelganger angle, moved the action to the North Pole, and had his group fight a brutish Karloffian “Killer Carrot from Outer Space” -- and I say that reverently -- that needed their blood to propagate its species and conquer the planet, leading to several team members hanging from the rafters by their ankles, completely bled out (offscreen).

Personally, from the setting, to the monster’s eating habits and modus operandi, I still see a lot of Vogt’s Black Destroyer and a touch of Discord in Scarlet in Bixby’s screenplay. But remember, it was Campbell’s story that inspired Vogt, who inspired Bixby, who inspired O’Bannon -- a maddening four-headed ouroboros of influences that will forever be left to conjecture and film nerd-offs, never to be sorted and settled properly as all the players involved are no longer with us: Campbell died in 1971, Bixby in 1998, Vogt in 2000, and O’Bannon in 2009.

And I cannot stress this enough: the goal here was not to indict, disparage, or accuse anyone of anything but to simply shine a light on what came before that adds texture to the ever-changing current.

Now, when the script was completed, Blaisdell did get to read it before committing and liked what he saw. Said Palmer, “There were none of the multiple monsters that had bogged down his work in Invasion of the Saucer Men; there were no outlandish props to be made, as there had been for Attack of the Puppet People (1957) and The Amazing Colossal Man (1957); and no one expected him to redress the She-Creature and cheat paying audiences by pretending it was something else," which he wound up doing under protest for Voodoo Woman (1957) and The Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow (1959).

Shamokin News-Dispatch (September 24, 1958).

Kent also had no problem meeting Blaisdell’s salary requirements, which was a helluva lot more than AIP ever paid him. Blaisdell had worked with Cahn before, several times, at AIP. They got along well, and he also got along with Bixby. As Blaisdell told Palmer, “Jerry wrote a helluva script in my opinion, and we had no problems figuring out what a Martian lizard-man should look like.”

Originally envisioned as a sleek, lightning fast monstrosity in the script, Blaisdell had a few other ideas. Said Palmer, “[He] wanted to give the lizard-man an expanded, barrel-like chest to suggest the enormous lung capacity a living being would need to survive in the thin atmosphere of Mars, along with a large, upturned nose with flaring nostrils. He decided that since it was supposed to be a carnivore, it would need to have a row of needle-like fangs like those of history’s most infamous killer, the Tyrannosaur. And because it was more reptilian than mammalian, it should have scales and prodigious strength. It would be a massive creature … Everything about it was going to be big -- big eyes, big teeth, big claws, big feet.”

But the Honeymoon on this new endeavor soon ended as things went slightly awry from the design stages on. Before, with the exception of the little cabbage-headed aliens in Invasion of the Saucer Men, Blaisdell had always worn his monster suits and portrayed them in the movies, explaining why his monsters were always so short. Here, he would be demoted as Small insisted that Ray “Crash" Corrigan play the Martian to add some bulk to the suit and add some punch to the marquee.

A former Hollywood physical fitness guru to the stars, Ray Benitz soon landed roles and performed his own stunts in a ton of serials like Undersea Kingdom (1936) and The Painted Stallion (1937). He also had long recurring roles with The Three Mesquiteers (1936-1939) and the Range Busters (1940-1943). As his star rose, Benitz would change his name to Ray Benard, then Ray “Crash” Corrigan after his character in Undersea Kingdom, and by 1940 he was simply Crash Corrigan.

Like Gemora, Corrigan was also a well known gorilla man, appearing in dozens of films with his homemade suits. In fact, some of his first roles were as a gorilla -- Tarzan the Ape Man (1932) and Murder in the Private Car (1934). He would also appear as the Orangopoid in the Flash Gordon serial (1936) and a giant sloth in Unknown World (1948).

By the 1940s, problems with alcohol had brought Corrigan’s career full circle as all he was getting offered were roles as a gorilla in things like The Ape (1940), The Strange Case of Dr Rx (1942), Captive Wild Women (1943), and The White Gorilla (1945). In 1948, Corrigan sold all of his gorilla suits to Steve Calvert, who took over. Details are a bit sketchy, but, apparently, anything that Corrigan’s recognizable gorilla suit appeared in after that was most likely inhabited by Calvert -- Forbidden Jungle (1950), Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla (1952).

Ray "Crash" Corrigan (left).

Things kinda dried up for Corrigan after that as his drinking problem persisted, resulting in his brief foray into television with Crash Corrigan’s Ranch (1950). After that, his acting career officially hit the skids; and after a few bit parts -- Apache Ambush (1955) and Zombies of Mora Tau (1957), Small decided to give him some work. In hindsight, good intentions or not, this probably wasn’t the wisest of moves.

To start off, the surly Corrigan refused to show up for any measurements and, instead, sent Blaisdell a pair of his long-johns to build the suit around, which he did, stuffing it with newspaper to approximate the stuntman’s girth. Then, individual scales of various sizes were glued on, piece by piece, to give the skin a crocodile texture. This method allowed for more flexibility by the wearer -- and Corrigan would need all the help he could get. The three-fingered hands and feet were made the same way, with everything attached to a heavy-duty pair of work gloves and a pair of sneakers respectively, including the massive claws, which were sculpted out of wood.

With solid financial backing from United Artists, Blaisdell had the means to experiment, making the Martian his one and only creation that used a negative rubber mold for the headpiece. It was sculpted to his "big" specifications with the teeth, nose, and eyes -- the ears required a little tweaking to make them larger and more flared. Of course, with more money, that also meant more hands in the pot.

The problem here was two-fold. First, he ran into trouble with his producers, starting with Kent, who liked the design but wanted the Martian to have even bigger eyes. As ordered, Blaisdell adjusted the mask, inserting two plastic orbs to embiggen the optic receptors. But then, when he took it to the studio, Kent was nowhere to be found but Small was there, who took one look at the headpiece, hated the eyes, and ordered them removed over Blaisdell’s protests. After the eyes were removed, Blaisdell returned to the studio and this time found Kent, who got upset and wanted to know what happened to the eyes he'd requested. “Ask your boss,” said Blaisdell as he turned and left.

As fellow gorilla man Bob Burns -- who was Blaisdell’s longtime friend and associate, told Palmer, “That was such a prime example of studio indecision. ‘It’s got to have big eyes!’ ‘We don’t want those eyes!’ ‘Where are the eyes?’ Paul had to add some more latex to the mask after the eyes came out, and then of course Ray Corrigan couldn’t see anything half of the time. There’s actually a scene in the film where Corrigan readjusts the eye-holes in the mask so he can see. They never bothered to cut it out of the film.”

And that, of course, was the second problem with the head sculpt. Again, since Corrigan had refused to show up and provide his measurements (-- he at least could’ve given a hat size), Blaisdell was forced to cast the mask off of his own head sculpt, which was considerably smaller than the actor’s massive cranium.

Thus, when it came time for the official fitting, Corrigan could barely fit into the suit and the separate headpiece didn’t fit at all. One panicked phone call later and Blaisdell was once again at the studio, where he saw Corrigan’s bulbous chin sticking out of the monster’s distorted mouth. Luckily, makeup artist Lane Britton had an idea and quickly painted the stuntman’s chin to look like a protruding tongue. It worked well enough; and with a hastily constructed set of bottom teeth to make the Martian look like it was snarling and not derping, the suit was finally ready to shoot.

The shoot itself only lasted for 12 days and Corrigan had reportedly shown up drunk and surly for all of them, which resulted in the infamous scene where we first glimpse the monster's shadow on the cargo bay wall. Here, Corrigan had refused to put the ill-fitting mask on and you can clearly make out the very human profile of his head, hair and nose on the hulking body.

This led to yet another problem as Corrigan kept living up to his name by constantly crashing into everything. Not only that, but he kept playing the reptilian monstrosity as if it were a gorilla, aping it up, meaning the suit was in constant need of repair.

Now, in the interest of equal time, according to actress Elaine DuPont, who was married to Corrigan at the time, swore in an interview with Tom Weaver (Science Fiction Confidential, 2002) that, “Crash never drank in his life. Never.” At the time of shooting, Corrigan was nearly sixty years old, was out of shape, and sealed into a costume that barely fit and he couldn’t see out of, all the while trapped under some very hot lights. I would be a little surly, too. So, drunk or dehydrated -- or both, I’d wager. Regardless, IT! The Terror from Beyond Space would be Corrigan’s last screen appearance.

The film would also be one of Blaisdell’s last efforts, too. Said Palmer, “The atmosphere on the set was unfriendly and disjunctive. Tempers flared constantly.” Blaisdell was even run off the set by an assistant director who didn’t recognize him, saying,“It wasn’t the kind of loose situation we had at American International, where we’d all learned to work together. I never heard anybody kidding anybody, or anybody laughing. It was really a stuffy, sad sort of set.”

His final film appearance would be a year later in The Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow, where he played the “ghost” -- a former monster maker, who’d been cast aside; and his final speech of abandonment by his bosses rang a little too true and brings some melancholic gravitas to that stinker, which the film so thoroughly did not deserve. Then, after turning down the usual cheap offer from Corman to provide the monsters for Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959) and Beast from Haunted Cave (1959), both of which sorely lacked the Blaisdell touch, he officially retired from the movie business.

Now, despite all of the off-screen acrimony and career ending experiences, onscreen Cahn and cinematographer James Peach managed to hold things together on IT! The Terror from Beyond Space and delivered quite a remarkable film. There are some genuinely creepy -- the discovery of Keinholz's body, gruesome --.the abuse of Gino's corpse, and harrowing moments -- Calder constantly holding the Martian off with the blowtorch, that still hold up when viewed today.

Eddie Cahn had a reputation for being quick and cheap, but also effective. Clocking in at a brief 69-minutes, the director lived up to that rep and really amped-up the tension and suspense by keeping things trim and tight and visually murky -- and kept Corrigan in check by keeping the monster in the shadows or limited to very brief glimpses until it went on a rampage; like Steven Spielberg would do some fifteen years later when his own temperamental monster failed to cooperate.

As for Bixby’s script, I love how at first the isolated ship essentially dooms the crew by trapping them with no possible means of escape -- Heusen even refers to it as a perfect escape-proof prison for Carruthers, but then ultimately provides their salvation by offering the only means to finally kill the damnable thing! And the added touch of Carruthers initially being framed for the horrible crimes he did not commit was an effective starting point to get everyone up to speed before the first reel ended and the monster makes itself known. And it’s nothing but a running fight from there.

Couple all of that with an eerie, punctuating score by Paul Sawtell and Bert Shefter, which sharp ears will recognize as being totally recycled from Kronos (1957), along with the claustrophobic setting, the relentless pace (-- marked by each death and evacuated floor), and a solid cast of can-do character actors -- anchored by Marshall Thompson, Ann Doran and Dabs Greer, and the end result is one of the most solid B-Movie efforts to come out of the 1950s.

Sure, there are a few anachronistic touches that will give you a few chuckles; like all the smoking these astronauts do inside the controlled environment of the ship. Or how no one seems to be all that concerned about the hull's structural integrity while firing off hundreds of rounds of ammunition, detonating several grenades, and popping off a few rounds from a bazooka. We've already addressed the passive misogyny when it comes to the daily routines, and I'm not even going to bother to poke the insipid love triangle between Carruthers, Heusen, and Anderson with the sharp stick it so thoroughly deserves.

In the build-up to its release, Kent and Small looked to not-so-subtly influence audiences through subterfuge by inserting brief subliminal flashes into the trailer, encouraging folks "To See IT!" and warning them "Don't miss IT!" nine times in total. Also, I have no idea if anyone was able to prove that the Martian didn't really exist and claim the $50,000 windfall offered by a "World-Renowned Insurance Company" in the film's posters and promotional campaigns -- or find him a mate or win a free trip to Mars as some ad-mats touted, before the offer expired, but I kinda doubt it.

The Los Angeles Times (October 1, 1958).

When it was released, the double-bill did well enough financially that Kent and Small immediately reunited Cahn with most of the production crew to churn out the even quicker and cheaper two-punch combo of The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake (1959) and The Invisible Invaders (1959) -- which, to add insult to Blaisdell's injury, just recycled the Martian monster suit from IT! to represent the non-corporeal alien invaders that inhabit the reanimated dead.

Alas, lightning failed to strike twice at the box-office; but still, over the ensuing years, Kent and Small would continue to turn out many a gonzo feature, including a couple of Vincent Price vehicles -- The Tower of London (1962) and Diary of a Madman (1963), before culminating with the biopic that Ed Wood so desperately wanted to make: The Christine Jorgenson Story (1970).

As for who inspired what, when, and how, I think most of it can be chalked-up to Hollywood's penchant for constantly cannibalizing and then regurgitating back-up what had come before. And by the 1970s, when JAWS (1975) showed the major studios what a B-Movie with an A-Budget could accomplish at the box-office, it was only a matter of time before somebody picked the bones of IT! The Terror from Beyond Space and others films of its ilk, threw a ton of money and talent at it, and wound up with an even finer feature film, which in turn spawned many a rip-offs and homages. Thus and so, and so it goes...

Originally posted on March 13, 2000, at 3B Theater.

IT! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958) Vogue Pictures :: United Artists / EP: Edward Small / P: Robert Kent / D: Edward L. Cahn / W: Jerome Bixby / C: Kenneth Peach / E: Grant Whytock / M: Paul Sawtell, Bert Shefter / S: Marshall Thompson, Shirley Patterson, Kim Spalding, Ann Doran, Dabbs Greer, Crash Corrigan.

%201958.jpg)

%201979_20.jpg)

%201958.jpg)

%201958.png)

%201958.jpg)

%201958.jpg)