"School's out, teacher!"

As three small town school teachers drive across the California desert toward Los Angeles, and a baseball game at Chavez Ravine, they come upon a homestead / service-station / salvage-yard along a lonely stretch of a very misguided short-cut. Officially in the middle of nowhere, and since their car's engine has developed a serious hiccup, the driver pulls through the entrance to hopefully have the problem both diagnosed and fixed in time to still make the first pitch.

No one greets them, but, it being a Sunday and all, they just assume the station is closed. With nothing else to do while Ed Stiles (Alden) tinkers with the damaged fuel-pump on his own, the other two passengers, Carl Oliver (Russell) and Doris Page (Hovey), start exploring the rows of old derelict cars and empty buildings.

And while they wander about, there are plenty of ominous signs that something isn't quite right here -- an empty table with a meal uneaten, a cut phone-line; and as these foreboding clues keep adding up, we can't help but conclude something most sinister is afoot. Alas, our three protagonists are too slow to put all of this together before they're all staring down the barrel of a .45 automatic...

I freely admit as a Nebraskan, born and bred, we as a State, an entire entity, suffer from a massive inferiority complex. We hayseeds, sodbusters, and shit-kickers all have a chip on our shoulder the size of Lake McConaughy (-- buy a map and figure it out), and we will rabidly defend our place in the Union by hoping our lack of uniqueness will somehow make us unique.

What else do we have to be proud of? Our biggest claim to fame is having one of the dullest stretches of any Interstate (-- though I think eastern Colorado is the worst); Johnny Carson, Harold Lloyd, Marlon Brando, Henry Fonda, James Coburn, Daryl Zanuck, and a lot of other famous people were born or grew up here -- but I point out they all left; and the schizophrenic weather, with all four seasons known to occur within the span of a few minutes, aren't really tourist attractions either. We do have a pretty cool zoo in Omaha, though, so, there's that. And then there's that whole Charles Starkweather thing.

E'yup, we had the nation's first fugitive spree-killer. Yay us. Now. For those few of you who are unfamiliar with this sentient shit-stain, Charles Raymond Starkweather was born November 24, 1938, in Lincoln, Nebraska; the third of seven children for Guy and Helen Starkweather. His father was an often unemployed carpenter due to chronic rheumatoid arthritis and his mother worked as a waitress to keep the family afloat. One of their son’s school teachers would later testify that “[the family] was poor, and they didn’t have as good of clothes as some children, but they were always clean.”

But Starkweather would later recall nothing positive of his time at school. Quite the opposite actually. Born with a birth defect -- genu varum, which gave him bowed-legs and a pigeon-toed gait; this was compounded by his short stature (-- Starkweather would max-out at five-feet, five-inches), degenerative, myopic eyesight that was diagnosed late and required thick glasses, and a slight lisp, which got him picked on mercilessly by his classmates. All of that plus his bright red hair, often worn in shorn flattop, earned him several nicknames, ranging from Little Red to Half-Pint to Firefly to Archie -- a reference to Archie Andrews from the comic books, of which the boy was apparently a fan.

When he entered high school, the only subject Starkweather really excelled at was gym class, which helped fill out his body as the boy matured and eventually turned the tables on his tormentors -- usually with a switchblade. But it didn’t end there. In an interview with William Allen for his book, Starkweather: The Story of a Mass Murderer (1976), Bob Von-Busch, a high school friend, talked about Starkweather’s growing mercurial behavior, saying, “He could be the kindest person you've ever seen. He'd do anything for you if he liked you. He was a hell of a lot of fun to be around, too. Everything was just one big joke to him. But he had this other side. He could be mean as hell, cruel. If he saw some poor guy on the street who was bigger than he was, better looking, or better dressed, he'd try to take the poor bastard down to his size.”

At home, Starkweather’s only interests were guitars and guns. His older brother, Roger, later pointed out that his sibling was a crack-shot who always went for the head when they hunted game. He also testified how “Charlie” never shot just once but would always empty the weapon at his target -- and how he would also gleefully empty his gun at no target at all. Starkweather also had a passion for hot-rods and his pride and joy was a souped-up ‘49 Ford that he co-owned with his father. But despite all of this hell-raising, Starkweather had no brushes with the law and no juvenile record. In fact, the only blemish was a misdemeanor citation over a traffic accident, where Starkweather tried and failed to teach his new girlfriend how to drive.

Caril Ann Fugate (few-gate) was born in July, 1943, the second of two girls for William and Velda Fugate, who would later divorce. Velda would eventually remarry, and Caril and her older sister, Barbara, would live with their mother and their new step-dad, Marion Bartlett, which soon netted her a new baby step-sister, Betty Jean.

By most accounts, Caril Ann was a precocious child with a “certain elfish charm.” She first met Starkweather in late 1956 by mere happenstance, through Barbara, who was dating Von-Busch at the time -- the two would later marry. Starkweather was 18 at the time, and Caril was only 13, but the girl was soon enamored by the boy with the red hair and the piercing green eyes, who kinda looked like James Dean (-- if you squinted real hard), a persona Starkweather was purportedly obsessed with and had tried hard to emulate since seeing Rebel Without a Cause (1955). These amorous feelings were mutual and the two would wind up “going steady” for nearly a year and a half. And when I say, “going steady,” I mean they had sex. A lot. Apparently, “Archie” Starkweather had found his Veronica.

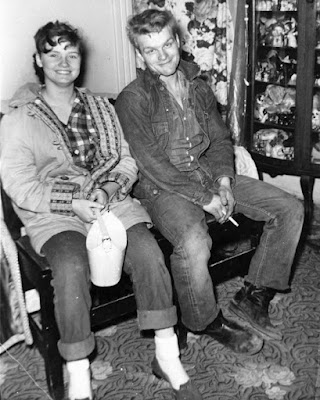

Fugate and Starkweather.

Now, it was during this obsessive courtship that those driving lessons commenced and things started to unravel for Starkweather. Apparently, Fugate was behind the wheel of the family Ford when she lost control and plowed into another car. This led to quite the dust-up with his father over the totaled vehicle, which had been driven illegally by a minor, which made them liable, who wound up kicking his son out of the family home over the incident.

Not long after, Starkweather dropped out of high school and got a job at the Western Newspaper Union, a warehouse that stored huge rolls of newsprint. In an interview with Majorie Marlette for the Lincoln Journal Star (January, 30, 1958), John Hedge, the WNU manager, commented that Starkweather came off as rather “worthless” and “weak-minded” on the job, but honestly, “[He] never made enough of an impression on me that I can’t even remember when he started work.”

Starkweather took the job because it was located near Fugate’s school, who was now 14 and in the 8th grade. He would visit her almost every day and walk her home. Meanwhile, Fugate’s parents didn’t think much of Starkweather, and perhaps it was time to put an end to what they felt was an unseemly relationship after a pregnancy scare.

Meanwhile, not lasting too long at the warehouse, Starkweather next landed a job as a garbageman. All the while, despite her mother’s best efforts, his romance with Caril continued, which allegedly included several marriage proposals that were also shot down by her parents. Thus, Starkweather started entertaining notions of running off with Caril, but for that they would need money. And to those ends, sometime in late 1957, he started making plans to possibly rob a bank.

Then, things continued to escalate when he was fired from his latest job for laziness and lack of effort, which in turn got him evicted from his boarding house when he could no longer make the rent. His ego took another blow when his eyesight continued to worsen, which had been reduced to 20/200, one notch below being declared legally blind. Thus and so, if he was going to act on his impulses to change his station in life, Starkweather would have to act sooner than later.

After he was captured and sentenced, Starkweather’s father, in an effort to explain his son’s aberrant behavior, revealed how Charlie was once hit in the head by a falling 2x4, which knocked him senseless, and how “he was never the same since.” But noted criminologist, Dr. James Reinhardt, thought his troubles went a little deeper than that -- or at least more deeply seated.

Dr. Reinhardt, who held a position at the University of Nebraska, interviewed Starkweather at length while he was on death row -- for nearly thirty hours. He would later write an article that was picked up by the AP and subsequently published in newspapers all over the country as he tried to explain, “What Made Starkweather Kill?” He would also publish a book on this same conundrum, The Murderess Trail of Charles Starkweather (1960).

According to Reinhardt, his subject matter thought the world was already against him early on -- “perhaps from his first days at school, when his flaming red hair, arched legs and short stature invited caustic nicknames,” which developed “an overwhelming sense of outrage that only grew in his mind a need for revenge upon the world.” And as he grew older, these nihilistic notions continued to fester into “a compulsive drive for dominance and public recognition. Socially, he was simply an empty man … his life purpose had no scope. Egoistic and biological satisfaction, that was about all. A girl to use, a gun to shoot, and power that could be tasted … The only way he could be important was by killing.”

And with all of that roiling just below the surface, looking for any excuse of a match to light the fuse, things reached a flashpoint when Starkweather wound-up in a bit of a feud with a certain service station, who would not sell him a stuffed animal for Caril on credit. And after casing the joint several more times, on December 1, 1957, Starkweather entered the premises with a shotgun, cleaned out the till of almost $160, and then, not wanting to leave any witnesses, abducted the 21-year old attendant, Robert Colvert. He then drove his victim to a secluded area along Superior Street just outside of Lincoln proper, where Starkweather later testified they struggled over the gun before he freed himself and shot Colvert in the back of the head, killing him.

Now, it would be nearly two months before Starkweather would kill again and officially start his murder spree. As for what happened next, there are two different versions depending on who was doing the telling -- Starkweather or Fugate, and who you believed. And so, for now, we’ll just plow ahead and try to sort it all out a few paragraphs down.

What isn’t in dispute is that Caril attended school on January 21, 1958. It was the middle of winter, there was snow on the ground, and the temperature was hovering around the freezing mark when the bell rang to end the day. But when she got home after class that afternoon, she found Starkweather at her parent's small frame house in the slightly seedy section of Belmont, engaged in another row with her mother. This ended in violence with Starkweather shooting both her mother and stepfather in the head with a .22 rifle. He then clubbed two-year old Betty Jean with the butt of the gun, fatally fracturing her skull. They then moved the bodies to the outbuildings in the backyard -- her stepfather went into the chicken coop while her mother and baby sister went into the pit below an old outhouse, made lunch, and then watched TV, drinking Pepsi and eating potato chips, as they argued over what to do next.

In an effort to keep what they had done hidden, the couple hung a makeshift sign on the front door, saying the house was under strict quarantine with a bad flu(e)-bug. But as the days passed, relatives soon grew suspicious, despite Caril’s insistence that they were just following doctor’s orders as she turned them all away at the door -- including a welfare check by the Lincoln police. Thus, this ruse worked for nearly a week until Caril’s grandmother, who feared what Starkweather might’ve done, insisted the house be searched, which finally was by Von-Busch and several others on Monday, January 27. By then, the couple had fled but the bodies of the three victims were found.

Meanwhile, as the authorities were informed of this grisly discovery, the two fugitives fled the city and headed south toward the small town of Bennet, where a family friend of the Fugate’s lived on a nearby farm. Here, sticking with the theme, Starkweather shot 70-year old August Meyer in the head, and then killed Meyer’s dog for good measure. The couple then ransacked the house, possibly looking for money.

Fleeing the scene, their car soon got hopelessly mired in the mud on a county road, forcing them to abandon it. They were then picked up on foot by a couple of teenagers -- Robert Jensen and Carol King, who offered to give them a lift into town. Instead, these good samaritans were hijacked and forced to drive to an abandoned storm cellar near a demolished school house. Starkweather first marched the boy to the entrance and then shot him six times in the back of the head. He then retrieved the girl from the car, forced her into the cellar and then attempted to rape his victim but was unable to “perform.” And in his anger over this, he stabbed the girl repeatedly before shooting her.

Using Jensen’s car, the couple returned to Lincoln on Tuesday, January 28. While working as a garbage collector, Starkweather was familiar with the city’s more wealthy and affluent neighborhoods and drove them to the home of noted industrialist, C. Lauer Ward. Here, Ward’s wife, Clara, and the family maid, Lillian Fencl, were taken hostage and physically restrained in an upstairs bedroom, where they were later stabbed to death. By whom? Well, we’re getting to that. Meantime, when Lauer finally returned home later that evening, Starkweather shot and killed him. Then, after ransacking the house, they packed up their loot into the Ward’s ‘56 Packard and hit the open road, heading west toward Wyoming.

When the Wards and Fencl were discovered later that evening, the authorities quickly linked the growing number of bodies in the area together and felt they were all done by the same perpetrators. Paranoia gripped the city and surrounding counties -- already on the prod after a grisly murder-suicide, where a father fatally shot and killed five members of his family and then himself in the nearby town of Beatrice that very same week (-- from the January 22, 1958 edition of The Beatrice Sun), and the Lincoln police department, who were taking a lot of heat for bungling the case thus far, called for a house to house search for the two fugitives, while Governor Victor Anderson quickly mobilized the Nebraska National Guard to help patrol the city.

But Starkweather and Fugate were already long gone. And when they crossed over into Wyoming on Wednesday, January 29, they needed to ditch the Packard, which had been identified as a suspicious vehicle on several news broadcasts, and find another car. Thus, when they came upon a traveling shoe salesman asleep on the side of an empty stretch of road, Starkweather approached the vehicle and then fatally shot Merle Collison. The couple then set about removing the body and transferring their belongings to the other vehicle, but didn’t realize the parking brake had been engaged -- a new feature Starkweather wasn’t familiar with, which stalled the engine when he tried to move it.

Here, the couple’s damnable string of good luck finally ran out as a passing motorist stopped to see if he could help. Thinking there'd been an accident, Joe Sprinkle got out of his car and was immediately confronted by an armed Starkweather. An ex-Navy man, Sprinkle went for the gun and a fight ensued, which in turn drew the attention of a passing Natrona County Sheriff’s Deputy, William Romer. Seeing the cop, Starkweather quickly withdrew and fled in the Packard. Meantime, Fugate, left behind, ran toward Romer, screaming, “It’s Starkweather! He’s going to kill me!”

Starkweather was then pursued by Romer, the nearby town of Douglas’s police chief, Robert Ainslie, and Converse County Sheriff, Earl Heflin. Their pursuit exceeded speeds of 100mph before a bullet fired by Helfin shattered the Packard’s windshield; and whose detonated glass cut Starkweather on the forehead; nothing serious, but it produced a lot of blood. And with that, he stopped and rather meekly surrendered. Later, Starkweather would claim if he’d had a gun handy he would’ve killed them all or gone down in a hail of bullets. A boast Sheriff Heflin quickly rebutted, saying, "He thought he was bleeding to death. That's why he stopped. That's the kind of yellow son-of-a-bitch he is.”

Thus ended Charles Starkweather’s reign of terror, which, thankfully, ended before it ever really got started. I know that sounds callous with the 11-bodies on the ledger, but what I mean is: It’s strange that something so heinous that left such an indelible mark on the nation’s psyche, all of that carnage and bloodshed happened in less than a week; and only two days had passed since the discovery of Fugate’s family on Monday and their apprehension in Wyoming on Wednesday, with everything else that had happened squeezed in between during those manic 48-hours. Basically, it could’ve been even worse if not for the timely efforts of Sprinkle and Romer.

Still, it sent quite the jolt through the entire State -- and in hindsight, the entire nation as their deadly spree made headlines across the country. My mother, who was 13-years old when these two were on the loose, honestly doesn't like talking about it all that much; it scared her pretty good. What little she recollected was how everyone was scared and how the deadly couple were allegedly spotted in the nearby town of Hastings at one point -- as I'm sure they were "allegedly" spotted in every other small town at the time; and how her folks wouldn’t let her or her siblings go out -- not like she wanted to at the time, she added; and how they kept the doors and windows locked and a shotgun, also locked and loaded, stationed by every entrance. And it wasn’t just in Nebraska as the couple was also falsely spotted in Ames, Iowa, Kansas City, Missouri, and as far south as Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Now, here is where our tale kinda diverges in a he said, she said, sense. Initially, it appeared Fugate had been a hostage during this whole ordeal. She would claim when she got home from school that fateful day, all she found was Starkweather, who claimed her family was being held hostage by a couple of accomplices and she had to do everything he said or they would be killed. She claimed to have no idea her parents were already dead and had to be sedated after getting hysterical when she got the news. And if you go back through and read all of the first news accounts after their capture, the general consensus was that Fugate was, indeed, also a victim of her psycho boyfriend’s deadly rampage.

In a rare moment of penitence, Starkweather would lament, “Since I was a child I wanted to be an outlaw, but I didn’t want it to go this far.” He would also back-up Caril’s claims at first, saying she had nothing to do with any of it, insisting she made at least four or five attempts to escape during the whole ordeal, and this was all on him. But this sense of remorse and nobility didn’t last very long and he would wind up recanting everything.

Guilty of a capital crime in two States, Starkweather chose not to fight extradition back to Nebraska, later petulantly claiming he preferred the electric chair over Wyoming’s gas chamber. He also refused to fly, meaning the couple were driven back to Lincoln. And it was during this transition that Starkweather turned on Fugate, claiming she was not only a willing accomplice to what had transpired but an active participant.

Thus, while she claimed she thought her family was still alive, Starkweather said she was not only there but was the one who killed her little sister because the toddler wouldn’t stop crying. And as his own versions of events continued to evolve, he would also claim it was Fugate who stabbed and shot Carol King in a fit of jealousy, which she denied, saying she never left the car. He also said it was Caril who stabbed Clara Ward, and insisted she was the one who wound up shooting Merle Collison when his shotgun jammed. “She was one of the most trigger-happy people I’d ever met,” Starkweather would later testify.

Caril, of course, stuck with her hostage story, but, true or not, public opinion on the depth of her involvement officially turned when a two-page letter, found on Starkweather when he was apprehended, was entered into evidence, which turned out to be a dubious confession, allegedly written by the both of them while at the Ward residence, which was to serve as a dying declaration if they were both killed while being apprehended, where they admitted to everything they’d done -- together.

However, the couple would be tried separately. Starkweather first on the sole charge of murdering Robert Jensen -- the only murder he would be tried for, and the only one he freely admitted to committing without a bullshit claim of self-defense, saying all the others had tried to hurt him first. Now, his defense attorney tried for an insanity plea, but their client got angry when they started to question his mental competence, saying, “I’d rather burn.” And after a short jury deliberation, he was convicted and sentenced to death. And while waiting for this sentence to be carried out, the inmate claimed, “I would be glad to go to the chair tomorrow if I could have Caril on my lap.”

Thus, Starkweather would be the star witness in Fugate’s trial, who testified to her involvement in the murder spree. Fugate, at the time the youngest female in the United States to ever be tried for first-degree murder, continued to claim she was a victim, but faltered badly during cross-examination. And combining that with the “confession” letter, the girl was found guilty and received a life-sentence. But Fugate would only serve 18-years at the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women before she was paroled in 1976 for good behavior, when the State felt they had taken “their pound of flesh.” She would move to Michigan upon her release and, as of this writing, Fugate is still alive but has staunchly refused all overtures to discuss what really happened -- except to maintain her innocence.

Starkweather, meantime, was executed at 12:04am on June 25, 1959. He had no last words, and it was reported he was totally indifferent about his impending death “and had resigned to his fate.” But in one of the last letters he wrote to his parents, he stated that, "I'm not real sorry for what I did cause for the first time me and Caril have (sic) more fun."

As to who was telling the truth over what actually happened? Well, I think the verdict is still out because all of the other witnesses to these crimes were killed. There’s no question about Starkweather's guilt. As to the extent of Fugate’s? Well, I’ve gone back and forth on this several times, taking into account her age, her shaky explanations, and Starkweather’s deviant tendencies, and I'm still not sure; but, again, we may never know what really happened.

What we do know for certain is how much of a strident chord this deadly outburst struck as the story blew-up all over the country. This was a whole new different kinda gun-nut than, say, outlaw bandits like Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, "Machine Gun" Kelly or John Dillinger, who came before them. They were all a reaction to the Great Depression and became folk heroes. But Starkweather and Fugate were a reaction to what exactly? Getting left behind during the Eisenhower, post-war boom? Perhaps. And unlike all of those others mentioned, their brand of killing was not for monetary gain but seemingly without reason or motive.

Thus, the growing scourge of juvenile delinquency had taken a new and dangerously lethal turn. And advocates against things like rock ‘n’ roll music, violence in popular media, and the decline of moral values had themselves a new poster couple to vilify as they smashed records and burned comic books; and a new phrase entered our pop-culture lexicon: the thrill-killer.

Over the subsequent years since their spree ended, Starkweather and Fugate's homicidal relationship would serve as the basis for several films -- most notably Terrence Mallick's Badlands (1973), and its influence spawned a whole genre in the 1990s about trailer-trash with guns in films like Dominic Sena’s Kalifornia (1993) and Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers (1994).

Now, Badlands is a beautiful and elegiac film that bent over backwards to romanticize its Starkweather and Fugate surrogates -- Kit and Holly (Martin Sheen, Sissy Spacek), and succeeded; but perhaps succeeded too well and to the point of being kinda disingenuous to its source material if we’re being honest. Look, I like that film a lot, but it does bind the relationship by framing it around the outbursts of violence. Which, I guess, is better than what came later, which reversed this by romanticizing the violence by framing it around the gung-ho relationship of the leads and, well, I have no patience for that kind of crap. Sorry.

Still, Badlands debuted almost fifteen years after Starkweather got the chair in ‘59. Seems Hollywood was reluctant to tackle the sore subject of this new breed of mass murderer; and while they wouldn't touch the likes of Starkweather, Richard Speck or Charles Whitman with a ten-foot pole, many a’ smaller, independent production companies were, forgive me, quicker on the trigger.

Technically, to my knowledge, one of the first attempts to adapt the Starkweather-Fugate boilerplate was actually on the small screen in a 1962 episode of Naked City (1958-1963), "A Case Study of Two Savages.” Here, Rip Torn and Tuesday Weld make quite the impression playing our surrogate bumpkin spree-killers, Ansel Boake and Ora Mae Youngham, who have just arrived in New York City from the hills of Arkansas in the pre-credit sequence.

They met just eight days ago, says the narrator, and got married two days later. And in the six days since, they’ve “shot and killed a gas station attendant in Kentucky, knifed a hotel manager in Pennsylvania, and murdered a hitchhiker they picked up in New Jersey."

This killing spree continues once they reach the big city, shooting a detective and killing another motorist in a road rage incident; then a bartender, and a gun store clerk as the plot gets a tad convoluted when Boake won’t steal his girl a wedding ring but is willing to rob a bank for the $10,000 needed to buy the one she wants, which gets Lt. Parker (Horace McMahon) and Detective Flint (Paul Burke) on their trail and nets us a spectacular climax at the bank in question.

All part of a twisted sense of logic as Torn brings a sly but volatile edge to his take on Starkweather. And there’s little doubt to Ora Mae’s involvement either, serving as a deadly muse for Boake, who seems to be doing all of this killing to make her happy in a way that is justified and will only make sense to them; and she’s armed and shooting during that climax, too, as Boake is gunned down. And when she is apprehended and questioned as to why they did all of this, all Ora Mae can do is just shrug and sigh, “Just for the hell of it, I guess.”

The episode does well to show the stark dissociation and detachment of these two killers, who appear to be a couple of romantic newlyweds one minute, playing around in their hotel room, or taking in the sights, and then killing someone the next without remorse or a second thought for the victims -- just a perverse means to a perverted end.

Starkweather actually gets name-checked during the episode, too, as Parker and Flint try to get inside the head of their suspects and run the trigger-happy couple to ground. The series, obviously, was a spin-off of Mark Hellinger's Naked City (1948), a most excellent police procedural, where a killer is doggedly run down by the police. And the apple didn't fall too far from the tree as far as the series goes, despite a bit of a rotating cast. (It took me half an episode to realize lookalike Paul Burke wasn't James Franciscus, whom he replaced after the first season.) Last check a bunch of episodes, including this one, are currently streaming on YouTube.

As for the first big screen adaptation -- again, to my knowledge, came a year later in 1963, courtesy of Fairway International Pictures and the father and son duo of Arch Hall Sr. and Arch Hall Jr. And judging by what those two had done before, cinematically speaking, you never would’ve guessed they'd have this good of a movie in them. Coming on the heels of Eegah! (1962), their giant caveman on the loose epic, the generational Halls unleashed this criminally underrated gem of a film: an honest study in unbridled brutality and mounting terror and tension called The Sadist (1963).

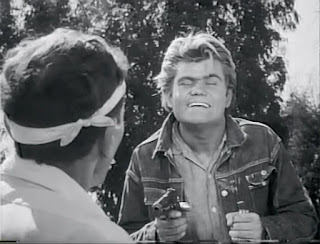

Now, the finger on the trigger of that automatic pistol I described earlier -- way, way earlier, sorry, belongs to Charlie Tibbs (Hall Jr.), a thug of the highest caliber. And with his jailbait girlfriend, Judy Bradshaw (Manning), hanging on his arm, doing her best to encourage him, Tibbs starts to torment this hapless trio of travelers as she constantly whispers into his ear, egging him on, and giving him ideas that are the equivalent of somebody pulling the wings off a fly before squashing it.

Quite obviously, Tibbs relishes his position of power, especially when he finds out this latest batch of victims are all school teachers, which is then amped-up even more by the cowed reaction of his captive audience. Here, Stiles is the first to realize these two must be the spree-killers that have been making headlines lately, blazing a trail of robbery and murder through three States.

Tibbs doesn't deny this and gladly gives a play-by-play on how they wound up here, in the middle of nowhere, stranded with a broken-down car (-- that was stolen after they killed the previous owner); and they had just killed the gas station owner and his family, too, when they heard the others pulling in. And itching to move on, Tibbs already has his beady little inbred eyes on their car until Stiles warns the fuel pump is shot.

Knowing they're all on borrowed time, the man offers to fix it -- with a hope of stalling things along until they can call for help or engineer an escape. Tibbs agrees, but makes no secret of his intentions to kill all of them as soon as the car's fixed. Here, Oliver, the eldest of them, tries to reason with their captor but only gets pistol-whipped for it. Then, turning a lecherous eye toward Doris, Tibbs playfully uses her and Oliver for a little target practice until Stiles refuses to do any more work on the car unless he leaves them alone.

But Judy has a better idea anyway, and whispers this into her lover's ear. Liking the idea, our mad-dog killer makes Oliver get on his knees and beg for his life; and he only has a narrow window to make his case, too. See, he only has however long it takes Tibbs to finish a bottle of soda-pop before his life will end! And as his executioner takes a long swig, again and again, Oliver's pleas for help from his friends and mercy from the hoodlum prove fruitless as the bottle is emptied. Tossing it away, Tibbs then cocks the trigger and thrusts the gun right into his victim's face!

Now, this is a critical point in The Sadist -- if not thee critical point; and it's a pivotal moment for the audience, too. Sure things began creepily enough: there were plenty of clues that we're made aware of, as an audience, but not our protagonists that something is wrong -- the cut phone lines, signs of a struggle, and just an overwhelming sense they're being watched by somebody thanks to a subjective camera. Our suspicions are then confirmed when that .45 is thrust on screen, nearly taking up the whole frame; then the camera whirls around and we're suddenly face to face with our "sadist" -- whom we B-Movie zealots will quickly recognize as the unmistakable mug of Arch Hall Jr.

Now, Junior’s performance as Charlie Tibbs is anything but restrained; and over-the-top doesn't even begin to do it justice. He strikes odd poses with the gun, and his drawl and inflection come off as slightly retarded as he starts to put our protagonists through the wringer -- both physically and emotionally.

And then you get the first uneasy inkling that this film is a whole different breed of juvenile delinquent thriller when the ever-giggling Tibbs goes through a groveling Oliver's wallet; first tearing up his baseball tickets, and then pictures of his family. This sense of uneasiness is reinforced when he next accosts Doris and actually sticks his hand up her shirt and roughly cups a feel of her breasts.

Whoa -- What the hell? Can this truly be happening? Is Arch Hall Jr. actually being menacing? Well, honestly, Junior's ham-fisted delivery still has us hearkening back to his other juvenile delinquent pictures, like The Choppers (1961) or Wild Guitar (1962), and other authoritarian, albeit hilarious, entries in this particular genre. I'll admit, up to this critical juncture, I was laughing at old Arch, too.

With that highly-pitched nasally voice and perpetual squint, all topped off with that concrete pompadour, his performance, for some reason, was reminding me of a young and pudgy Wayne Newton -- back when he was doing guest spots on Bonanza. But then we reach that pivotal moment when Oliver's time runs out:

Tibbs, with the .45 in hand...

Ignoring his victim's pleas for mercy...

Sticks the gun point plank in Oliver's face...

And pulls the trigger.

*Bang*

Holy shit! What the hell just happened?!

Like Tibbs, the camera does not flinch during this scene. We see the whole thing. Here, I'll pause to remind everyone that this was 1963 we're talking about; and I'm curious if this was the first time we actually see someone get shot in the head without the aid of a jump-cut?

Apparently, there was an even more graphic take of Oliver being shot with a special-effect squib that involved the offal and brains of a sheep, which either didn’t pass muster or they couldn’t get it past the censor and was left on the cutting room floor. And to make that scene even more harrowing, Landis insisted on fifteen takes as he tried to get the FX-gag to work to his satisfaction -- so spare a thought for poor Don Russell, who had a blank popped off in his face over and over again with only a thin protective sheath between him and the gun. Also of note, there are plenty of substantiated rumors that the production also used live ammunition on set to keep things more real.

And after this extremely shocking moment, everything afterwards, even though Junior's character is doing the exact same thing, and he's acting the exact same way, everything that seemed silly and insipid before honestly becomes bone-chilling and, in some cases, downright terrifying!

In an Arch Hall Jr. flick?! Are you kidding me?! No. I'm not. And I'll even take it one step further and say this whole movie is pretty damned good, even though it's become cliché, retroactively; spoiled by a lot of psycho-degenerate / white-trash serial killer films that followed. Is that fair? I don't think so. And yeah, it is hard to believe when you look at the Hall family oeuvre as a whole.

Arch Hall Sr.

See, Arch Hall Jr. was the protégé of his father, Archibald William Hall the Senior. Now Senior was a genuine cowboy from South Dakota, who was fluent in Lakota and often lived-up to his native nickname, "Waa-toe-gala Oak-Shilla" (The Wild Boy). Back in 2014, in a rare interview with Sean Weathers for his Full Circle Movie Talk podcast, Junior talked at length about his father and how he wound up in Hollywood.

It started when his parents sent Senior to St. Louis, Missouri, for his schooling. Upon graduating high school, he then worked his way through the Great Depression repossessing cars until the delinquent owner of an Oldsmobile caught them in the act, pulled a gun, and shot and killed his partner, thinking they were trying to steal it. After, Senior moved back to South Dakota with his tail between his legs, regrouped, worked a little in radio, and then decided to head west to see if he could make it in the movies.

And according to Junior, to get there, his father rode the rails like a hobo. And a harrowing journey it was, too, as he often related the tale of how two other transients tried to roll him while he slept in a makeshift “hobo jungle.” Senior fought back, and things quickly got out of hand. And while he managed to prevent the robbery and escape, Senior spent the rest of his life unsure if he hadn’t actually killed someone while defending himself that fateful night.

He finally arrived in Hollywood in the late 1930s, where he quickly caught on; first as a stuntman, and then as an actor -- with his first credited role being in Overland Stage Raiders (1938), co-starring with John Wayne, Ray "Crash" Corrigan and Louise Brooks. And Senior continued to work as an actor -- mostly Poverty Row westerns, until around 1945 with Border Badmen (1945), when he enlisted in the Army Air-Corps as a pilot at the tail-end of World War II.

Strangely enough, Senior’s time in the service as a geriatric glider pilot was made into a film by Jack Webb of all people. It was written by Bill Bowers, who had served with Senior during his time in the Air-Corps. Bowers had written for Bob Hope -- My Favorite Spy (1942), Alias Jesse James (1959), penned several seminal film noir pieces -- Criss Cross (1949), Cry Danger (1951), and wrote one of my all time favorite westerns, The Gunfighter (1950). Now, The Last Time I Saw Archie (1961) would chronicle the comical misadventures of Bowers, played by Webb, who would also produce and direct, and his best friend Archie Hall, played by Robert Mitchum, and the film is a bit of a hoot -- if you can find it.

In an interview with Boyd Rice for Research #10: Incredibly Strange Films, Ray Dennis Steckler, another protege of Senior’s, who would go on to write and direct the likes of The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies!!? (1964), The Thrill Killers (1964) and Rat Pfink a Boo Boo (1966), said of The Last Time I Saw Archie, “Bill wrote [the film], it was a hit novel; the only problem was that he had to have permission to use Arch’s name. Bill said he’d take care of him and Arch signed a paper. Of course, Arch never got a thing for it; the studio never gave him anything.”

Despite getting skunked out on his own autobiographical film, Senior landed on his feet well enough after he got out of the service, leveraging his way into several lucrative real estate deals, which would prove profitable enough that he decided to form his own production company in 1959, make some films, and keep all the profits for himself.

Based out of Burbank, Fairway International Picture’s first exploitation feature would follow in the footsteps of Russ Meyer -- The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959), Eve and the Handyman (1961), and Herschell Gordon Lewis -- The Adventures of Lucky Pierre (1961), Living Venus (1961), with their own Nudie-Cutie, Magic Spectacles (1961) -- also released as Tickled Pink, where a medieval scientist devises a pair of magic x-ray specs that allows the wearer to see beneath the clothing of others, which are then discovered a century later by a yutz who goes on a grand “sight-seeing” adventure. Senior would produce Magic Spectacles, which was written by his only son, Arch Hall Jr.

Now, all Archibald W. Hall the Junior ever really wanted to be was a pilot, just like his old man. But Senior got it into his head that he could turn Junior into a crooning teen heartthrob; and over the span of three short years Fairway International assaulted the drive-in circuit with three critically disclaimed low-budget "classics” as a showcase for Junior’s “talents,” starting with The Choppers, where Junior rocked-out with tunes like “Monkey in My Hat Band” and “Congo Joe” while running a stolen car ring. “Nice kid, pretty good musician, but he wasn’t much of an actor,” said Steckler.

According to that podcast interview with Junior, The Choppers was actually the first film shot for Fairway International, which started filming back in 1959. It went way over budget and way over schedule, forcing Senior to leverage his home and several properties for completion funds. Then, things got worse from there when they tried to distribute the independent film across the country regionally. At the time, most distributors and exhibitors required a double-bill and The Choppers had no second feature. And all efforts to find one already done to latch onto it went nowhere; and so, the film basically sat on the shelf for several years until Fairway International managed to scrape enough funds together to make a second, even cheaper feature themselves.

Both Junior and Senior would star in this second feature -- which was soon promoted to the top of the bill, that aforementioned caveman epic, Eegah!, whose plot origin can be traced back to one of Senior’s tenants being several months behind on the rent. That renter? Richard Kiel, whom Senior first spotted as a bouncer at a nightclub, who needed a place to stay. Senior got him a room at one of his rental properties, and the 7’2” giant agreed to play the title role to make-up for those delinquent payments. Kiel, of course, would later go on to minor infamy playing the James Bond villain, Jaws, in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979).

Senior would also direct Eegah! to save money -- under the name of Nicholas Merriweather, one of his many aliases. He also hired Steckler to run the camera for him and to direct second-unit on the picture. The two had met during the production of Secret File Hollywood (1962), where Steckler was an assistant cameraman and Hall played an uncredited bit part in that dirt-cheap sleaze-noir that finds an ex-detective digging up dirt on celebrities for a tabloid scandal sheet. Steckler would also put in a couple of cameos in Eegah!, volunteering to be thrown into the pool by the rampaging neanderthal for the climax, and appearing with his future wife, Carolyn Brandt, as a couple of necking teenagers who get peeped on by the curious caveman.

Ironically enough, Eegah! and The Choppers made their theatrical debut at a drive-in in Omaha, Nebraska, where it managed to pull in about $15,000 on its initial roll-out. Harry Medved and Randy Dreyfus interviewed Senior for their book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time, where the producer talked about promoting Eegah!, which made the list, tucked in between Dondi (1961), which deserved to be there, and Godzilla vs the Smog Monster (1971), which did not. “We went on tour to promote the picture, and the personal appearances were very successful,” said Senior. “My son would strum out the Eegah! theme on his guitar, and the lights would go down low. All of sudden, Kiel would come out with his suit on and his club. People went wild. They just loved that giant. Sometimes they mobbed him, and they’d almost rip his clothes off. I never saw anything like it.”

With each of their movies proving barely successful enough to form the minuscule budget for the next one, the two-punch combo of Eegah! and The Choppers proved enough of a hit to pull out all the stops on Wild Guitar, where the budget went from squat to squat-and-a-half. Here, Steckler made his directorial debut with a kind of meta tale of Junior becoming an overnight singing sensation through the machinations of his crooked manager (played by Senior) and his hired muscle (played by Steckler). It’s a total goof of a film, with just enough of Steckler's signature absurdity to push it in the win column -- for me at least.

Alas, with all the perceived acting talent of an avocado, Junior never really took off or caught on as an actor like his dad had hoped. And after starring in Fairway’s next double bill, consisting of the spy parody The Nasty Rabbit (1964) and the western Deadwood ‘76 (1965), Junior officially called it a career, got his pilot’s license, and became a commercial aviator. Senior was crushed by this development. “I always felt, to be honest, that Arch was just attempting to relive his youth through his son,” said Steckler in the Boyd interview. “It was a big disappointment that [Junior] didn’t want to continue in the business. The minute his son stopped making movies, Arch stopped making movies. He didn’t have the desire to go out and tackle the industry without his kid in the picture.”

Thus, when Junior walked away from the acting business, Senior stopped producing, too, and the world of schlock cinema is lesser for it. Then, after surmounting a ton of debt accrued during Fairway International's six picture run, Arch Hall Sr. died in 1976 -- not long after being interviewed by Medved and Dreyfuss; and at last report, Arch Hall Jr. was still flying, is a grandfather, and living in Florida, from where he respectfully declines most offers to discuss his film career.

Now, right smack dab in the middle of the Rise and Fall of Fairway International and Arch Hall Squared came The Sadist. But it was two other men, I believe, who should be properly credited for elevating this movie above the rest of Fairway’s usual dreck: James Landis and Vilmos Zsigmond. Senior would only serve as the producer and uncredited narrator on the film -- once more under his Merriwether disguise, while the writing and directing chores fell to Landis.

Landis was a fellow South Dakotan who broke into the business working for Robert L. Lippert under the Regal Films banner, making quick and cheap second features in CinemaScope for 20th Century Fox, by writing or directing or doing both on several war films -- Under Fire (1957), Thundering Jets (1958) and Airborne (1962), as well as a couple of crime capers, where the main character was the bad guy trying to go straight in Young and Dangerous (1957) and Stakeout (1962). And he would later write and direct a fantastic but obscure nasty little piece of sleaze called Rat Fink (1965), where another young sociopath murders his way to stardom that more people really, really need to see.

For The Sadist, Landis employed a no-nonsense, documentary-style approach that served his sparse script well. And as the first attempt to adapt the Starkweather-Fugate murder spree on film, this matter-of-fact style resulted in a pretty taut and merciless thriller that will knock you right on your ass -- because this was the last thing you were expecting when you saw who was on the marquee.

Zsigmond -- here billed as William Zsigmond, served as the film's cinematographer, and his set-ups, lighting, and creative framing give The Sadist a certain … terrified look -- a razor-blade starkness, and a down and dirty grittiness that gives the film most of its cinematic punch. And I love how we keep switching perspectives: one minute we are on one side of the gun looking down the sight, the next we're staring right down the barrel; it's simple but effective in keeping us off balance. There's a lot of effective handheld camera work, too, getting us down in the dirt and in the middle of the action -- I swear the camera barely gets over three-feet off the ground for half the picture; and the frame never really does stand still once the ball gets rolling, giving the narrative a frenzied sense of momentum that keeps us barreling toward the climax.

Another one of those gifted craftsmen who worked their way up the film food chain, Zsigmond’s career began with Fairway International Pictures -- he was one of Steckler’s guys, who worked the camera on Wild Guitar along with Joseph Mascelli, who later went on to write one of the seminal books on the craft, The Five Cs of Cinematography (1965). Zsigmond, along with his friend and fellow cameraman, Laszlo Kovacs, had fled Hungary in 1956 when the revolution against the Soviet Union controlled government heated up and Khrushchev sent in the tanks to quash the dissent.

Both would become heralded figures of The New Hollywood era of the 1970s, with Kovacs shooting films for Bob Rafelson -- Easy Rider (1968), and Peter Bogdanovich -- Targets (1968), What's Up, Doc? (1972) and Paper Moon (1973), while Zsigmond shot for Robert Altman -- McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), The Long Goodbye (1973), John Boorman -- Deliverance (1972), Michael Cimino -- The Deer Hunter (1978), Heaven’s Gate (1980), and Steven Spielberg -- The Sugarland Express (1974), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), for which he won an Academy Award -- even though he was nearly fired off the picture early by the studio.

As I mentioned in an earlier review of Steckler’s Incredibly Strange Creatures… on the old bloggo, a film Zsigmond, Kovacs and Mascelli all worked on, their type of guerilla filmmaking meant they would fit right in with these new young turks of Hollywood. But I always appreciated how they never forgot their exploitation roots, thanking guys like Steckler and Arch Hall Sr., or Al Adamson -- Satan’s Sadist (1969), Five Bloody Graves (1969), or Harry Novak -- Kiss Me Quick (1964), Wonderful World of Girls (1965), and Dave Friedman -- A Smell of Honey, a Swallow of Brine (1966), The Notorious Daughter of Fanny Hill (1966), for giving them a chance when no one else would, which got them their union cards and allowed them to ascend that Hollywood ladder.

Thus and so, when combining Landis and Zsigmond’s efforts with a $33,000 budget, a two-week schedule, a cast of five, one location, where the days were long, the sun was hot, and both cast and crew slept in their cars, these two concocted a film that is relentless, brutal, and very downbeat that definitely deserves more notoriety. So why don't more people know about it?

Well, it didn’t help that Fairway International’s distribution was fairly sketchy and only had a real foothold in the mid-west and southern drive-in circuits. The film was later re-released in 1971 under the alternate title, Sweet Baby Charlie, and it played on TV as Profile in Terror. And so, to anybody who actually did see it, they’re all remembering it as three different movies. Is this why The Sadist isn’t considered a bona fide cult classic?

Well, despite the jumbled titles, and with all respect to Junior and his gonzo performance -- which he later claimed was based not on Starkweather but on Richard Widmark’s psychopathic Tommy Udo from Kiss of Death (1947) even though he technically never saw that movie, it’s the rest of the cast that does the most damage. Mention of a positive nature should be made for Marilyn Manning's equally understated performance as Judy Bradshaw -- and it's hard to believe that these same two people played those two brain-dead teenagers in Eegah! just the year before.

According to Senior, Manning was a perky receptionist for a chiropractor that rented office space from him. Senior was smitten and she wound up starring in three films for him -- Eegah, The Sadist, and What’s Up Front (1964), another brainless Nudie-Cutie about the world’s greatest brassiere salesman. That, sadly, would be the extent of Manning’s film career. But she leaves quite the impression as Tibbs's deadly muse, who, like Ora Mae, always seems to be the true trigger for her boyfriend’s homicidal outbursts. To her it's just a game, and between her sinister urging and the scenes of her rifling the dead for souvenirs, well, her performance is kinda creepy and disturbing.

So, that means the biggest problem lies with our three protagonists; characters so paper thin to begin with, which is then compounded when the actors don't really add anything to them. Don Russell fails as the voice of reason, and Richard Alden comes off rather stiff in a performance I can’t quite decide as being either brilliant-by-accident or completely annoying. You'll occasionally catch a hint of an accent from Hovey, a cousin of the film's star. She's a gamer, but never acts like she's in any real danger; like she hasn't quite got the difference between “acting” and “pretending” down yet, so some of the menace is lost. To be fair, she does get better as the movie progresses. But as the film plays out, dare I say, Alden makes for a better "final girl" than she does?

To be honest, there are no likable characters here. Well, Carl Oliver, maybe, but he's already dead. I mean, Tibbs and Judy, our thrill-killers, are sociopathic vermin, and Stiles comes off as a sniveling coward, while Doris is -- well, as I hinted before, she is kind of a helpless cipher whom you'll be yelling, "Run, you idiot!" at. A lot.

And there are several chances for escape, too, or to take Tibbs on, but Stiles keeps wimping out -- but it’s a believable kind of wimping out, so we can empathize with him a little. (Again, is it a good performance or a bad performance, dammit?!) Their biggest chance to escape comes when two passing motorcycle cops stop for some refreshments. Alas, the hostages wait too long to warn them, allowing Tibbs to get the drop on these would-be saviors before they’re shot dead.

However, even with each dashed hope, and with every missed opportunity continuing to stack the deck against our victims' life-expectancy, as things continue to ratchet up even more, you're still conditioned to expect a happy resolution -- but it never comes. Evil isn't punished in the film. Evil only kind of devours itself; a hollow victory for the good guys and the audience.

It starts with a deft move by Stiles, who finally summons the courage to act; and then Tibbs, his face full of gasoline, accidentally shoots and kills his partner in crime. Now, up to this point, as I said, Stiles has kinda been a cowardly weasel but you figure now, that he's finally grown a pair, he'll come through and save the day, thus redeeming himself.

And, like Stiles, I was counting the number of shots Tibbs popped-off while chasing him. Thus and so, after a harrowing game of cat and mouse, when the gun finally clicks empty and Stiles finally goes on the attack -- and we, as an audience, look forward to finally seeing the mealy-mouthed Tibbs at long last get his head most righteously kicked in -- we, like Stiles, completely forgot about the stolen police revolver; and then sit in stunned silence when Tibbs pulls this second gun and kills his latest victim before he could even get close - let alone land a punch. And there will be no last-second heroics by a wounded Stiles, either, as Tibbs empties the revolver into him, punctuating that point with a gruesome finality.

Then, after another prolonged stalk and chase scene (-- that we'll be seeing again ten years later in Texas, if you know what I mean), Doris is saved by dumb luck and dumb luck alone when the pursuing Tibbs falls into an abandoned well, which proves a den for several rattlesnakes, which robs of us of any kind of emotional payoff.

And we end with Tibbs's death screams (-- that purposefully sound like a dying animal), as Doris, in a state of shock, slowly wanders back toward the junkyard as those resonating, primal shrieks fade to be replaced by the radio call of the unattended baseball game.

That. That is why you'll have a hard time shaking The Sadist once you've finally seen it, because you're angry at it -- and in hindsight, respecting the hell out of it -- for cheating us out of any kind of vindicated resolution. Just one of the many reasons why this film is truly remarkable and such a groundbreaking piece. And its influence can easily be seen in the equally relentless, cynical and brutal horror films of Wes Craven, Tobe Hooper, George Romero, and many others that followed -- and should be championed for this, and not lampooned because of the reputation of its leading man. Facts are facts: The Sadist was the first of its kind, is a one of a kind, and definitely deserves to be better known than it is.

Now. During this latest re-watch, and while digging into the history of Starkweather and Fugate for this expanded review, I was kind of amazed how many mythologized or embellished aspects of what he did went down in flames as you looked at the facts -- perpetuated by me, as well, as my old review of The Sadist was just teeming with factual inaccuracies that were based on whatever I pulled out of my ass, apparently, and not the actual truth.

When most people think of Starkweather, they think of the James Dean wannabe; hair slicked up, the slouch, the leather jacket, the boots, the defiant stare as a cigarette dangles from his lip, all make him seem bigger than life; but it’s all bullshit and a far cry from the diminutive, blind as a bat, bow-legged, pigeon-toed, dumb-as-a-post dipshit creep with the bright red hair he really was (-- I honestly had no idea he had red hair as all those old black and white photos make him look sandy blond). And then it hit me.

Starkweather was no James Dean. Nope. He was Arch Hall Jr. No. Wait. He wasn’t even Arch Hall Jr. He was nothing special at all. It was such a bizarre, meta-moment that caught me off guard when I first realized this, meaning it's probably nowhere near as profound as I am making it out to be for anyone else. Fine. Whatever. But, damn, if it ain’t appropriate when talking about The Sadist. And in this movie, Junior’s performance is quite startling. It’s really good. Honest. And Charlie Tibbs, not Jim Stark, is the real Charlie Starkweather. A slightly retarded, brain-dead teenager with a gun, who was lucky until his luck ran out, and not some pretty boy rebel without a cause.

Originally published on June 11, 2004, at 3B Theater.

The Sadist (1963) Fairway International Pictures / P: L. Steven Snyder / D: James Landis / W: James Landis / C: Vilmos Zsigmond / E: Anthony M. Lanza / M: Paul Sawtell, Bert Shefter / S: Arch Hall Jr., Marilyn Manning, Helen Hovey, Richard Alden, Don Russell

No comments:

Post a Comment