"Looks like I picked the wrong week to quit smoking."

We open knee-deep in World War II, winging our way toward Germany with the R.A.F.'s 72nd Fighter-Bomber Squadron. Under the command of Canadian pilot Ted Stryker, their mission is to bomb a strategic supply depot. And after slugging through the German fighter umbrella, things get a little sticky when the group's objective is completely obscured by a dense fog. But against the urging majority of his squad-mates, Stryker doesn't abort the mission and leads his planes in on a low attack run that ends in catastrophe.

Relying on instruments and instincts only, the planes go in too low and six of them crash. Stryker (Andrews) survives this disaster run but is badly wounded; and while recovering, the airman is crippled with survivor's guilt and haunted by severe, paralyzing flashbacks of the fatal attack.

Taking full responsibility for the mission's failure, no formal charges of negligence are brought against him but Stryker is officially washed-up as a pilot. And when he receives his medical discharge, his doctors warn the shell-shocked veteran to face his emotional trauma, and to put it behind him, or he’ll be running from it forever. For Stryker, the war is over, but “a more personal kind of war has just started for him."

Ten years later, Stryker is still running. Even now, desperately trying to land a menial factory job in Winnipeg, Stryker fears his sketchy war record will once again cost him another job. But the manager says it’s his record after the war that concerns him more. Seems Stryker has gone through twelve jobs in ten years, and has moved just as often. Obviously, this constant state of flux has also put a great strain on his family. And knowing he's at the breaking point with his wife, Stryker pleads for the opening to save his marriage, finds a sympathetic ear, and lands the job; but when he arrives home to celebrate, all the man finds is a note in an otherwise empty house.

Rushing to the airport, the desperate husband spies his estranged wife, Ellen (Darnell), and their son, Joey (Ferrell), boarding Flight-714 for Vancouver just as that note had indicated. Quickly buying a ticket for himself, Stryker barely makes it on board before the flight departs. Now, it's been over decade since this ex-pilot last left the ground, and after white-knuckling it through the take-off, he breaks into a cold sweat and quickly retreats into the bathroom, where he has a major relapse and suffers through an extreme anxiety attack, complete with violent flashbacks of his men crashing and burning.

Meanwhile, along with the three players of Stryker's crumbling marriage, there are several other subplots traveling on this prop-plane as well. Head stewardess Janet Turner (King) is squabbling with her long-time boyfriend, Tony Decker (Paris), because she can't get a matrimonial commitment out of him. There’s also a trio of older gentlemen in first class, passing a bottle around, on their way to Vancouver for a football game. And as the flight reaches a stable cruising altitude, the stewardesses start taking dinner orders, offering a choice of two entrees: lamb of fish.

When the rattled Stryker finally extracts himself from the bathroom, he bumps into the pilot in the galley. (What the pilot is doing in there, I don’t know -- and who's flying the plane is another mystery. Anyhoo...) Taking in his passenger’s flop sweat and haggard appearance, Captain Bill Smith (Hirsch, and his unearthly chiseled chin,) offers up some Dramamine when Stryker claims he’s just suffering from a little air-sickness.

Stryker declines and moves up the aisle to try and talk to Ellen, who isn't really happy to see him -- but Joey sure is. Wanting to speak with her privately, Stryker asks the stewardess if his son can see the cockpit. After Janet takes them both forward, recognizing him, Smith asks Stryker if he's feeling any better, then asks Joey if they’ve ever been in a cockpit before. Here, Joey proudly offers his dad used to fly fighter-planes in the war, and then proclaims he wants to be a pilot, too, someday -- just like his old man.

Before she leaves, Janet asks the flight crew which entree they'd rather have for dinner. Smith, the co-pilot (London), and Joey all want the fish, while Stryker opts for the lamb. When his dad says it's time to go, Joey is offered a chance to stick around for a while if he likes. He does. And as Stryker leaves, we overhear an ominous weather report over the radio that states several airports are closing, completely swamped in by a dense fog.

Returning to his wife, Stryker throws himself on her mercy and begs for another chance. But Ellen is firm on her actions and confronts him with the facts: the decision to leave was made for Joey's benefit, not hers, because they’ve been on the move since the end of the war, constantly uprooting, and never settling down, and that’s not fair to him. It’s nothing he’s done, she says, but what he hasn’t done. When her husband swears to do better, his promises are no good anymore. And then the wife drops the bomb: she can no longer live with a man she no longer respects. (Ouch.)

Back in the cockpit, Janet brings the pilots their food and sends Joey back to his seat. When the boy finds his dad not sitting with his mom, his father handles it delicately but the kid knows the score (-- and let’s give Joey a little credit here for being wise beyond his years). Then, things settle down as all 38 passengers are served a meal. They eat, and time quietly passes -- until one of these air-travelers becomes violently ill.

And when the Dramamine Janet administers has no effect on her passenger’s worsening stomach pains, fearing they may need to make an emergency landing to get the sick woman to a hospital, the attendant reports this incident to Smith. Unfortunately, with all the airports closed due to the inclement weather -- except for Vancouver, still five hours away -- all he can do is hold course and see if there is a doctor on board. But as Janet leaves to do just that, we notice the co-pilot is starting to get sick, too...

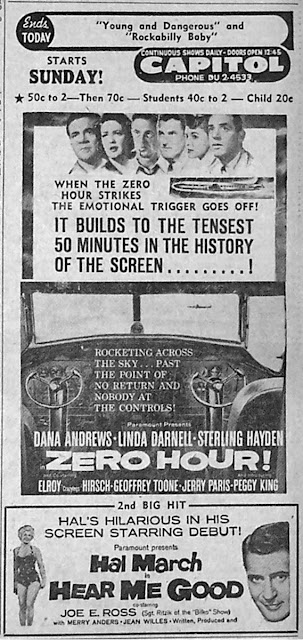

Well, now. Surely our plot thus far sounds kinda familiar to you? Maybe it’ll trip off your déjà-vu alarm just a little if I stopped calling you Shirley? It should. Well, it surely should if you’ve seen Jim Abrahams, David Zucker and Jerry Zucker’s comedy spoof Airplane! (1980). For if you have already seen Airplane!, it makes Hall Bartlett’s Zero Hour! (1957) quite the surreal movie-watching experience. But even if you haven’t seen Airplane!, this film is still quite the trip.

As the legend goes, Arthur Hailey first had the notion of a drama based on a calamitous airline disaster while a passenger on a commercial flight back in 1955. A native of Bedfordshire, England, Hailey started writing at a very early age. Finances kept him from pursuing this any further academically, leading to several menial jobs while he continued to write on the side. He joined the Royal Air Force in 1939 and served as a combat pilot during World War II, reaching the rank of flight lieutenant.

Once the war ended, Hailey migrated to Canada in 1947, where he settled in Toronto, Ontario, where he moved from job to job, mostly in advertising, but never abandoned his desire to be a writer. According to an interview with Les Wedman for The Province (October 11, 1956), Hailey wrote several pieces of fiction but failed to sell anything. He did manage to publish a few technical articles on aviation and served as an editor on several trade magazines but all that soon changed after that fateful flight.

For, just nine days later, Hailey had hammered out a script for Flight into Danger, which he sold to The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation for the princely sum of $600. “I don’t claim to be an expert on plays,” Hailey told Wedman. “I don’t go to the theater often. But I’m an avid movie and TV drama fan. Some of which are very good, and some of which are very bad.”

His script, which was plucked out a mailbag filled with hundreds of other submissions, quickly passed muster and went into production as part of the CBC’s General Motors Theater; a weekly anthology program that consisted of one-hour episodes of romance, drama, adventure, or mystery tales.

The gist of Hailey’s teleplay for Flight into Danger finds a passenger airliner in trouble mid-flight due to some acute food poisoning. Seems both the pilot, the co-pilot and over half the passengers have eaten some tainted fish. Luckily, the stewardess (Corinne Conley) manages to find both a doctor (Sandy Webster) and a pilot (a pre-Star Trek James Doohan) amongst the passengers who aren’t sick. Tensions rise as Dr. Baird’s diagnosis is grim, and the only hope these trapped patients have is to get them on the ground and to a hospital as soon as possible. Of course, that means someone has to fly and land the plane first.

And while George Spencer was a Spitfire pilot during the war, he hasn’t flown in years and isn’t sure he can handle the controls of the four engine Douglas DC-4. Told he is the only hope the other passengers have -- including Spencer’s young son, who also ate the tainted meat, the man takes the wheel with his wife (Kate Reid) by his side manning the radio. And the only thing that could make matters any worse is if there were a massive storm raging at the airport they’re supposed to land at, meaning Spencer will have to make an instrument landing, which is sounding more and more like the same scenario that happened to him during the war, which did not end well for anybody.

Flight into Danger made its broadcast debut on Tuesday, April 3, 1956 to rave reviews. And it proved so popular the CBC wound up exporting the episode worldwide, where it continued to garner critical acclaim and calls for more of the same kind of engaging drama for what was rapidly becoming known as The Idiot Box. And this notoriety might’ve helped General Motors Theater to be the first Canadian program to be imported to the United States by the American Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). Rebranded as Encounter, alas, the series only managed to air five episodes before it was unceremoniously yanked off the air -- though the exact reason why remains elusive. (Odds are good it was more interesting than the commercials.)

Now,

Flight into Danger was not amongst those five broadcasted episodes

because the rights to that story had already been sold to NBC, who then

remade it for their own anthology series, The Alcoa Hour, where

MacDonald Carey took over the role of Spencer, and featured co-stars

Patricia Berry, Liam Redmond and Geoffrey Toone. It was also remade in

Great Britain for Studio 4 (1962), and in Germany as Flug in Gefahr

(1964), and in Australia (1966). And it would be remade yet again in

America as a movie of the week for CBS as Terror in the Sky (1971), with

Doug McClure as the pilot, Roddy McDowall as the doctor, and Lois

Nettleton as the stewardess.

And after scoring such a big hit with his debut, with an ear for human intrigue and an uncanny knack for translating his obsessive attention to the minutest of details so the layman could understand them, Hailey was soon in demand and started cranking out more scripts, following up Flight into Danger for the CBC with Shadow of Suspicion (1956), Course for Collision (1957), Death Minus One (1958), Epitaph at Little Buffalo (1958) and Queen’s Peace (1960). He would also write Time Lock (1957) for ABC’s Kraft Theater, No Deadly Medicine (1957) for CBS’ Studio One, and Diary of a Nurse (1959) for Playhouse 90.

In 1959, Hailey would adapt and expand his Emmy nominated teleplay for No Deadly Medicine into his first published novel, The Final Diagnosis, which focused on the pathology lab of a rundown Pennsylvania hospital. And over the next decade, Hailey would split time between writing novels and writing screenplays. Meantime, Flight into Danger was also adapted into a novel by “John Castle” -- a nom de plume for authors Ronald Payne and John Garrod, which was released in America as Runway Zero-Eight in 1959. Hailey would get a co-author credit on this adaptation, and he would also get first crack at writing the screenplay for a proposed feature film version.

From what I dug up, there was a bit of a bidding war for the film rights to Flight into Danger, with Hailey finally settling on producers Hall Bartlett and John Champion's offer of $21,000. Bartlett was another washed-out actor who moved behind the camera. His first film was a documentary, Navajo (1952), where a young Native American boy is caught up in the massive culture clash between the new way and the old, which garnered two Academy Award nominations: one for Best Documentary, the other for Virgil Miller’s Black and White Cinematography. And this kind of social commentary would often wind its way through a lot of Bartlett’s future productions.

His second feature would be another docudrama, Crazylegs (1953), which chronicled the life and times of football legend Elroy 'Crazylegs' Hirsch on the gridiron. The producer would cast Hirsch again in his next feature, where he took the lead in Unchained (1955), another ripped from the headlines feature calling for prison reform, which Bartlett also directed.

Both Bartlett and Champion were triple threats, having served as producers, directors and screenwriters -- Champion mostly on westerns, a couple of which starred Sterling Hayden, which will be relevant here in a second. Flight into Danger would be their first collaboration and, as near as I cal tell, also their last. And while they did give Hailey first crack at adapting his original teleplay to feature length, the producers weren’t satisfied and started adding their own revisions.

First to go was the title, which they felt sounded too much like a lurid B-picture, and rechristened their film as Zero Hour!. Second, was renaming the protagonist, who was no longer George Spencer but Ted Stryker. And according to an article by Clyde Gilmour for the The Vancouver Sun (December 14, 1957), Bartlett and Champion were also responsible for cooking up most of Stryker’s backstory during the war, including the doomed mission and the resulting PTSD. And then they cranked up the melodrama even further and really piled it on to fill those extra 22-minutes by making this the root cause of the Stryker’s failing marriage, which got everyone on the plane in the first place.

Thus, we have reached the point of no return for Ted Stryker, as more and more passengers start getting sick, including Joey. Luckily, Janet finds Dr. Baird (Toone), who is happy to help and starts attending to the sick. But as he examines the boy, the doctor doesn’t like what he’s seeing in the presented symptoms -- acute stomach pain, chills, and profuse sweating. When Baird asks Ellen Stryker what the boy has had to eat, she goes through the whole day up to the fish he ate an hour ago. With that, Baird asks to see the pilot. When Smith meets him in the galley, the doctor insists they must land immediately. But then, before Smith can even ask why, the plane abruptly goes into a nosedive!

Rushing into the cockpit, they find the co-pilot slumped over the controls. And while Smith gets the plane back under control, Baird asks Janet what the sick man had for dinner. Told he also had the fish, and feeling for sure that food-poisoning is the likely culprit, the doctor asks for a tally on who else had the same meal. Unfortunately for all on board, the first name on that list is Smith, who ominously points out he had the tainted fish, too.

Thus, as the passengers start to grow wary that something's gone wrong, Smith radios Vancouver to have them prepare for an emergency landing, with medical help standing by. That done, Baird gives him a shot of morphine to help fight off the sickness. (Giving morphine to the pilot? Is that really wise?) The doctor also gives everyone else who had the tainted meat an ipecac, making one wonder what they’re going to do with all those soiled air-sickness bags? But this comes too little too late as more passengers fall victim to this deadly malady. And when Janet hears the intercom buzzing, no one in the cockpit responds to her answer -- which can mean only one thing!

With Baird right behind her, the stewardess rushes forward and finds Smith keeled over in his seat, barely conscious, but manages to turn the auto-pilot on, so they're safe for the moment (-- well, at least until they run out of gas or plow into a mountain). And since she managed to find a doctor amongst the passengers, Baird sends Janet out again; this time to not only find them a pilot, but to find a pilot who didn’t eat the fish.

To prevent a panic, they create a ruse, saying Captain Smith only needs help with the radio. As it turns out, Stryker is the only one with any kind of flight experience, who offers to help. But then, to his horror, as he enters the cockpit, the man finds both pilot seats empty! Thus and so, Stryker immediately tries to back-pedal out of this for myriad reasons, some very legit -- like how he only flew single engine fighters during the war, and how he has no idea how the advanced instrumentation works on this newer, larger plane, until Baird gives him the score: unless he can land the plane, everyone, including his family, will surely die.

With his hands full of unfamiliar controls, Stryker says he will need help with the radio. Here, Baird promotes Ellen to co-pilot. But when she is brought upfront and takes in the scene, she can't help but fearfully express her husband's short-comings to the doctor. (Read between the lines, here, folks.) But Baird insists this is their only chance, with no time for doubts or accusations. All they have to do is concentrate on landing the plane, Baird assures, while he and Janet take care of Joey and the other passengers. And as Ellen buckles in, Stryker contacts Vancouver and updates them on their ever-escalating emergency situation.

On the ground, the scramble to make preparations for that emergency landing is being overseen by a man named Burdick (Quinlivan), who picked the wrong week to quit smoking, which includes rounding up Captain Martin Treleaven (Hayden), whom he feels is the best man to talk Stryker down safely. But! Turns out these two men have a lot of bad blood between them and a troubled history that dates back to the war; and the caustic Treleaven has no doubt Stryker will most definitely crack under the pressure. (Making Treleaven Stryker’s former commander to add even more tension, and the resulting animosity, was another change instigated by Bartlett and Champion.)

Echoing Dr. Baird, Burdick stresses that Stryker is the one and only chance they have to get everyone down safely; and so, Treleaven puts on the kid gloves when he first contacts the plane. When Stryker recognizes him, they “cordially” agree to cut the crap and to just get on with it. With that, Ellen takes over the radio and Treleaven starts to familiarize his pilot trainee with the controls and landing procedures.

Meanwhile, despite Janet's best efforts, the other passengers have discovered the plane no longer has any real pilots and a panic ensues. One woman in particular even tries to open the emergency door, cutting her hand on some broken glass in the process. As Tony helps to get this hysterical woman under control, he sees that Janet isn’t holding up very well and promises to marry her as soon as they land to help perk her up. (Ya know, not much of a commitment, really, once you consider the circumstances, you jack-ass. Again with the anyhoo...)

Back on the ground, Treleaven wants to practice with the controls some more, but a stressed-out Stryker is a little preoccupied as the plane approaches the Rockies, where they run into a really bad thunderstorm. Making matters worse, the intense lightning and thunder trigger more flashbacks -- and Stryker kinda freezes up, then zones-out, causing the plane to go into another terminal nosedive!

Luckily, Ellen manages to snap him out of this funk in time to get the plane safely over the mountains; but during the mayhem, the radio was knocked off the airport’s frequency. Thus, as the ground-crew in Vancouver sits in an uneasy silence, the radio-op keeps calling for Flight-714 but gets no answer. On the plane, Stryker sweats some more and tinkers with the radio. Eventually, with Ellen's help, he manages to tune Vancouver back in.

Alas, the flight's erratic course has allowed that bad weather to catch up with them, and now Vancouver is swamped in by fog, too. Told they have enough fuel to last another two hours, Treleaven wants the plane to just circle the airport until the weather breaks. But Stryker radios back that the sick passengers are out of time and he’s coming in -- fog or no fog. Treleaven concedes and the doctor wishes them luck.

Taking the plane down into the soup, Stryker puts Ellen in charge of the engine kill switches, which need to be flipped after they land. And as they swing around for the final approach, Ellen looks her husband in the eye and says that she’s very proud of him. Eyes now front, they manage to faintly make out the runway lights through the fog and head in.

Here, Ellen sounds the alarm, warning the other passengers to assume crash positions; and as Treleaven bellows at them the whole way down -- they come in too fast, burn out the brakes, and destroy the landing gear -- the plane at long last comes to a screeching halt on its belly mostly intact. Mostly. (As the old saying goes, any landing you can walk away from…)

When things settle, Dr. Baird informs the couple they’ve landed in time to save the sick. Over the radio, and the approaching sirens, Treleaven says it was the ugliest landing he’s ever witnessed, but would still like to buy the man a drink and shake his hand.

Told ya! Yeah, from the deadpan doctor, to the cranky air-traffic

controller, to the sweaty hero, and from the plucky stewardess, to the

long suffering love interest, to the very panicky passenger, to a former

sports star as one of the pilots, it’s kind of amazing how verbatim Airplane! is to its source material.

Swiping everything, right down to the majority of the dialogue, the makers of the spoof didn’t change a whole lot because they didn’t really need to -- hell, it’s even the originator of “The picked the wrong day to quit smoking” gag that was expanded and taken to the hilt by Lloyd Bridges in the later film.

You can even draw a line between the wild impropriety of the “Have you ever seen a grown man naked” encounter with Peter Graves’ Captain Ouvre to a scene between Tony and Joey in Zero Hour!, where the older man uses a sock pocket that talks in a thick Irish brogue to entertain the sickly boy, which comes off as both hilarious and kinda creepy.

Like a lot of people, I had always assumed Airplane! was a direct spoof of the film Airport (1970), the franchise it spawned -- Airport ‘75 (1974), Airport ‘77 (1977), and The Concorde: Airport ‘79 (1979), and the cycle of disaster movies it helped inspire with the likes of Irwin Allen’s The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974). That is, I was under that assumption until I happened to catch Zero Hour! on cable sometime in the early ‘90s. It’s common knowledge now, sure, but back then? Nope. And as it played out, I was completely flabbergasted as my ignorance melted away at what a shameless grope Airplane! really was.

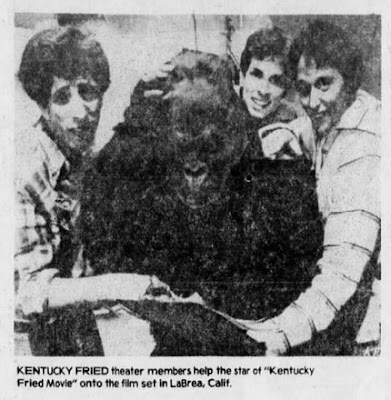

Jerry Zucker, (Rick Baker), David Zucker, Jim Abrahams.

How did this come about? Well, that’s a bit of a story that will require a really long aside. So, please bear with us as we tumble down this rabbit hole together. All set? Good. Okay. Seems after graduating from the University of Wisconsin in 1970, David Zucker was in Chicago where he saw an underground comedy show called Void Where Prohibited by Law, which he would later describe as “Seventy minutes of awfully primitive, grossly scatological sketches” but “I laughed until I had tears running down my cheeks.” He then returned to his home in Madison, Wisconsin, where he related to his younger brother, Jerry, what he had seen and was convinced they could do the same kind of show -- only different and better.

The Zuckers then recruited their lifelong friend Jim Abrahams and fellow Wisconsin alum Dick Chudnow, met up at a Kentucky Fried Chicken, and started hashing out premises, content, and tried to come up with a name for their new enterprise, eventually drawing dubious inspiration from the venue they were eating at; and thus, Kernel Sanders’ Kentucky Fried Theater was born -- soon shortened to just The Kentucky Fried Theater.

Setting up shop in a small room in the back of the Shakespeare and Co. bookstore in Madison, KFT would definitely be different than any other improvisational comedy troupes of the era; as their show would be a more scripted satire and multimedia affair, which would include live skits combined with filmed parodies and spoofs of movies, TV shows and oddball commercials, perfecting what early critics quickly dubbed “short attention span comedy.”

The show grew quite popular and quickly outgrew its original venue and, eventually, their hometown as KFT pulled up stakes and moved to Los Angeles around 1972, where they converted an old drug treatment center on Pico Boulevard into a combination theater and living quarters. There, the show would run for another four years. And while it proved equally popular, “We never wanted to spend our lives doing live theater,” said David Zucker in an interview with Tom McElfresh. No, what the brain-trust behind KFT really wanted to do was make a movie, and inspiration would come from a familiar source.

In an effort to find material to lampoon for the live show, “We used to set a recorder to tape off TV all night, because that’s when the stupidest commercials played,” said Abrahams in an interview with Aaron Lee for The Morning Call (February 2, 2008). “One night, we accidentally taped an old disaster movie, Zero Hour!. That was a fortunate break in our careers.”

“We’d never heard of Zero Hour! before then,” said Jerry Zucker in The Oral History of Airplane! for the Onion’s AV Club. “And at first we were probably sort of just fast-forwarding to the commercials, or maybe looking at but mostly just waiting for the commercials -- but then we started really watching it and getting into the movie. It’s a perfectly classically structured film.”

Thus, Zero Hour! became the backbone of their idea for The Late Show, a movie within a movie, which would basically recreate an evening of late night TV viewing with their send-up of the film being interrupted by a ton of faux commercials. They shopped this treatment around Hollywood but found no takers. And so, they decided to try and make the movie themselves.

Enter John Landis, who had just appeared on The Tonight Show to promote his independently produced feature, Schlock (1973). Landis was introduced to the KFT team through mutual friend, Bob Weiss, who took a look at their script, recognized the source material right away, felt they were well past the limits of parody when it came to copyright law, and encouraged them to secure the remake rights to Zero Hour! before going any further. This they did, from Warner Bros., for the princely sum of $2500. Still, no one was interested in actually making it -- except them.

It was either Landis or Weiss, depending on who you asked, who first suggested that if they really wanted to make a movie, and make it relatively cheap, they should just film The Kentucky Fried Theater skits. And so, The Late Show was shelved, and they sat out to find financing for a big screen adaption of the stage show. Again, no studio was interested in doing a sketch comedy showcase and what little nibbles they did find came with the total loss of creative control. Undaunted, they found a real estate developer who showed some interest if they would produce a 10-minute proof of concept reel first, who then balked and backed out when told this would cost $25,000.

Here, the Zuckers and Abrahams decided to just fund the demo reel themselves, which they would write -- with an assist from Pat Proft, Landis would direct, and Weiss would produce. (Most sources say it was the blaxploitation parody, Cleopatra Schwartz, along with three other fake trailers that were later incorporated into the finished film.) When it was finished, Landis thought it was hysterical but his partners weren’t as enthusiastic. To prove he was right, Landis made an arrangement with Kim Jorgenson, who owned the Nuart Theater in Los Angeles, to screen the reel before an evening feature. Apparently, the audience nearly died laughing, along with Jorgenson, who allegedly fell out of his seat. And so impressed was Jorgenson, he offered to fund the entire film to the tune of $650,000.

When it was released, Kentucky Fried Movie (1977) proved to be a hit, raking in nearly $7-million at the box-office. And with the money made off of that success, taking into account everything they had learned while making their first feature, the Zuckers and Abrahams removed themselves from the live show, holed up in a bungalow in Santa Monica, and took another run at what was now being called Kentucky Fried Airplane! since Robert Benton’s The Late Show (1977) -- a fantastic ode to hard-boiled noir, had been released in the interim. And as work progressed, the fake commercials were removed altogether and the entire film would be nothing more than an absurdist retelling of the original film.

“I know we didn’t appreciate it at the time,” said Abrahams for the AV Club, “but over the years we found that the jokes in the scenes that stayed closest to the plot of Zero Hour! were the ones that stuck around. Meanwhile, some of the other jokes that we thought were great but which didn’t have that much to do with the plot, they just sort of fell by the wayside."

And it was this version of the script that wound up at Paramount, via Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg, who, as it turned out, owned a half-interest in Zero Hour! that hadn’t been paid for yet, which might’ve been a factor as to why the Zuckers and Abrahams went with Paramount instead of Avco-Embassy. There was some give and take in these negotiations, with the Zuckers and Abrahams being allowed to co-direct the film en masse, maintain creative control, and not cast any comedians but straight actors. (As Robert Stack explained to a confused Lloyd Bridges when shooting commenced, "Lloyd, we are the joke.") In turn, they agreed to shoot the film in color instead of black and white like they wanted, changed the setting to a modern jet-liner instead of a prop-plane, and a title change to just plain old Airplane!.

Now, the rights to Zero Hour! weren’t the only legal hassles the production faced as Universal Studios' rabid trademark lawyers, who were notorious for litigating over their IP, keenly watched as things unfolded, ready to pounce and sue if anything even remotely resembled their Airport franchise. Seems the KFT crew wanted George Kennedy, who had played Joe Patroni in Airport, a character who would appear throughout the series, to play the role of Steve McCroskey, but had to turn them down on advice from his agent; and so, the part went to Bridges instead. (Kennedy would eventually work with the Zucker-Abrahams triumvirate in The Naked Gun franchise.) The same thing with Helen Reddy, whom they wanted to reprise her role as the singing nun from Airport ‘75. Again, the studio nixed this.

And it’s all rather strange as both Zero Hour! and Airport originated from the exact same source: Alex Hailey. See, Hailey’s big commercial breakthrough came in 1965 with the publication of his novel Hotel, which followed the lives of several employees and guests of the antiquated St. Gregory Hotel in New Orleans. This novel would solidify Hailey’s template of “ordinary people involved in extraordinary situations in a business or industry which is described in meticulous detail,” according to Peter Guttridge. It would be adapted into a film by Wendell Mayes, Richard Quine and Warner Bros. in 1967.

Hailey then followed that up in 1968 with his most best selling novel yet by moving the scenery to Chicago for Airport, where the staff of said commuter conveyance must deal with a huge winter storm, a stuck plane, a blocked runway, stowaways, and a flight insurance scam by a suicidal passenger, who brought a bomb aboard a flight to Mexico so his family can cash-in when the plane goes down, on top of several love triangles, extramarital affairs, and an unexpected pregnancy. Universal would adapt the novel into a film in 1970 with an all-star cast -- Burt Lancaster, Dean Martin, Jacqueline Bisset. Helen Hayes and Van Heflin, which led to a box-office bonanza and 10 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture.

All well and good, but what about Zero Hour! itself? Can it stand on its own? Well, that’s a loaded question that can only be answered by, it kinda depends. For if you can separate the two films, you can appreciate the tight, terse, and no-nonsense direction of Bartlett and some pretty nifty set-ups by cinematographer John Warren despite being so limited by his minimal setting, trapped on the plane like everyone else. Warren also shot films ranging from The Country Girl (1954) and The Seven Little Foys (1955) to The Daughter of Dr. Jekyll (1957) and The Colossus of New York (1958). As for Bartlett, the only other thing of note he did after Zero Hour! was adapt the feature length adaptation of Richard Bach’s new age existential de rigeur, Jonathan Livingston Seagull (1973).

In Airplane!, Robert Hayes needed help from the FX department to produce the gallons and gallons of sweat Ted Stryker exuded. Here, Dana Andrews didn’t need any help. (Man, that guy could produce the juice.) Both Andrews and Sterling Hayden turn in rock solid performances here, as does Linda Darnell as the long-suffering Ellen, who isn't afraid to pull any more punches as far as her husband is concerned. “Crazy Legs” Hirsch is surprisingly solid as Captain Smith, too. Solid enough it's kinda surprising this would be his last feature. And while Peggy King was a singer by trade, she also does just fine in her dramatic debut. (Also watch for John Ashley doing a very bad Elvis impersonation on a TV screen.)

I guess in the end it’s not that hard to see this plane ride as a metaphor for the Stryker’s failing marriage. And how they have to put their differences and doubts aside and work together to get through this crisis and save Joey. And with a little help from Treleaven -- the marriage counselor from hell, they manage to successfully land the plane in one piece, thus saving the marriage.

And to be honest, Zero Hour! does stand up fairly well on its own as a dramatic piece, but I will warn you all one last time that if you've already seen Airplane!, it makes Zero Hour! one of the funniest damned unintentional comedies ever made -- both a blessing, and a curse.

Originally posted on December 14, 2000 at 3B Theater.

Zero Hour (1957) Carmel Productions :: Paramount Pictures / P: John C. Champion / D: Hall Bartlett / W: Arthur Hailey, John C. Champion, Hall Bartlett / C: John F. Warren / E: John C. Fuller / M: Ted Dale / S: Dana Andrews, Linda Darnell, Sterling Hayden, Geoffrey Toone, Jerry Paris, Peggy King, Charles Quinlivan, Steve London

Another bit of trivia about Zero Hour that I love is that its success was a a factor in the CBC's supervising producer for drama getting summoned across the pond to work for the BBC. The producer was Sydney Newman, who'd go on to create the seminal british genre show "Adam Adamant Lives".

ReplyDeleteOh and also Doctor Who.

I had no idea about THAT either. I remember finding and following that thread in the research phase, taking notes, but failed to find a spot to incorporate it into the actual review -- that was about to collapse under its own weight already! Thanks for reading and taking the time to comment.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteEPIC!!! I learned so much!

ReplyDelete