Even though the title would imply something straight out of a J.R.R.

Tolkien hangover by way of Sidney Pink, it’s not exactly what we get. (And I pray I haven't just given some revisionist wonk any bright ideas. Trust me, I am way, way, way ahead of 'em.)

Nope. Instead, we get a mind-warping kiddie flick straight from the well-meaning but horribly misguided 1960s, which begins with a slightly off-key children's chorus bellowing their way through the insidiously infectious jingle, "Hooray for Santa Claus!"

We then open on a TV set tuned into the KID Network, whose anchor cheerfully announces since it’s almost Christmas they have a special report lined-up direct from Santa’s workshop at the North Pole. But! As we slowly rotate around to see who’s been watching, we’re in for a bit of a shock!

Now, unless all those threats about the dangers of sitting too close to the TV were true, we can most likely safely assume these green-hued children with the kitchen utensils drilled into their heads are Martians.

These assumptions prove correct as Bomar and Girmar watch with a cold detachment when the newscaster tosses it over to his wacky weatherman, Andy Henderson (Wertimer), live at the North Pole, who cracks some lame jokes about the subzero temperatures (as only a network weatherman can) while making his way toward Santa's Toyshop.

Inside, Henderson finds the elves hard at work under the supervision of the Big Red Cheese himself, Santa Claus, who appears to have been hitting the “holiday punch.” Like, a lot. (Yeah ... I think that 190-proof jolly red nose has finally been explained.)

Giving their visitor the nickel tour, Santa (Call) shows off one of the latest toys: a rocket that uses genuine rocket fuel! Next, when Henderson spots a familiar looking green doll discarded in a pile of wood-shavings, Santa says Winky (the weird elf) made that one, claiming it’s a perfect facsimile of a Martian.

And thus Winky invents the action figure, ushering in a dark chapter in the history of toy making, as hordes of speculators run over defenseless children to get their Martian, mint on card, to sell later for a sinful profit on eBay.

Here, our roving reporter ominously wonders if Mars has its own version of Santa, to bring joy to all the Martian children. But before he gets an answer, Mrs. Claus (Rich) comes in and starts cracking the whip, sending everyone back to work. Interview over, I guess.

But there is no joy on the Sad Red Planet, where High Lord Kimar (Hicks) finds his bumbling servant, Droppo (McCutcheon), sleeping on the job. And so, taking what looks like a cattle-prod, Kimar jabs it at the prone Martian.

But as Droppo flops around in a spastic fit, turns out the device is only a harmless tickle-ray. (And fair warning: Droppo will remain in this highly agitated state for the rest of the film.)

Meanwhile, Kimar and his wife-mate, Momar (Martin), openly worry about their children, Bomar (Month) and Girmar (Zadora). They won’t eat their food pills; won’t sleep without a healthy dose of the sleep-ray; and spend their entire days in front of the tele-screens, watching those silly Earth programs.

Case in point, with bedtime approaching, Kimar has to pry his kids away from the screen and set the sleep-ray to full blast. But this isn’t an isolated incident.

No. It’s the same way in households all over Mars, and Kimar doesn’t know what to do until Momar suggests they consult with the wise and ancient Chochem (Don), who's, like, 800 years old or something and should know what to do.

Kimar agrees and calls for a meeting of the high council, including the spiteful crank, Voldar (Beck), at the endless caves. Once there, Kimar calls to Chochem, who, in a puff of smoke, magically appears. And once the dilemma is laid out for him, the wizened old coot says their answer is obvious: the Martian children are rebelling.

From the day they were born, he says, they’ve been hooked into Martian learning machines and are adults before they can even walk. Thus, the listless children must learn to have fun. In other words: Mars needs a Santa Claus. (And Larry Buchanan kicks himself for not thinking of this movie first.) Then, in another puff of smoke, Chochem vanishes. (Wait, no he didn’t. He’s still there!)

In spite of the exalted source, Voldar thinks this is a terrible idea and doesn’t want to turn their children into mush-brained idiots like the Earthling's offspring. Besides, Where are they going to get a Santa Claus? Well, a desperate Kimar says, they’ll just have to go to Earth and get one.

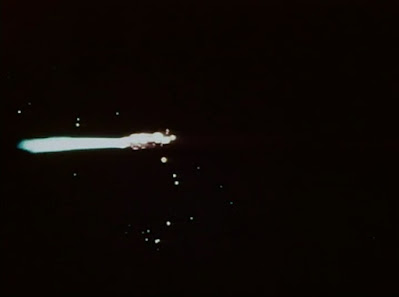

Thus, Kimar, Voldar, and a small Martian contingent board a giant Tinker Toy, blast off, and reach Earth in no time at all (-- but, I’ll point out, Voldar still bitched the whole way). Achieving orbit, the Martians start scanning and are shocked to find Santas scattered all over the globe. (They’re looking at several gents in Santa suits ringing the bell for the Salvation Army and such.)

Taking this as a good sign, Kimar feels with all these Santas around no one will ever miss the one they decide to abscond with. But before they can choose, several alarms sound off as their ship is scanned with terrestrial radar beams.

Now, that should be impossible but something's gone wrong with the ship's Radar-Jammer -- which has come down with a bad case of Droppo, who stowed away under the control panels. Nevertheless, the Martians quickly fly below the radar net and begin their search for a perfect, isolated victim.

Meanwhile, the nation is alerted that the U.S. military has detected a UFO and is scrambling the nation’s defenses (-- via stock footage). Of course, the Russians deny they had anything to do with this as we cut to two children, Billy and Betty Foster (Stiles,Conforti), sitting under a tree, listening to the news reports about the UFO and the wild speculations over the Martians invading the Earth.

Well, obviously, they are, and the children have picked the worst possible spot for their siesta as a Martian scouting party finds them.

Luckily for these Earthlings, Kimar says they’ve come in peace and are looking for a Santa Claus. When helpful Billy says there’s only one real Santa, who lives at the North Pole, Kimar is excited because there’s no more isolated place on Earth than that. (Oops. Way to go, kid.)

Still, Voldar demands they take the children with them so they can’t rat them out. Kimar reluctantly agrees. Thus, they load up their prisoners, blast off, and head north.

Along the way, the friendly Droppo lets the Earth kids out of the brig on the sly and gives them the grand tour, showing them the repaired Radar-Jammer and several other, vital pieces of equipment, which I am sure will come in handy later. Hearing the other Martians coming, Droppo quickly hides the children in the same spot he hid earlier.

Meanwhile, when the ship lands, Kimar orders Droppo to remain and guard the Earth kids while the rest go after Santa. And taking no chances, the Martians will activate TORG to take Santa down. What’s a TORG? I don’t know, but it doesn’t sound good.

Overhearing this, Billy and Betty sabotage the Radar-Jammer again, give Droppo the slip, and escape into the sub-sub-zero temperatures outside and disappear into the snow dunes to warn Santa. But as the Martian strike-force disembarks, Voldar discovers the Earth children have escaped.

Splitting his men into two teams, Kimar stresses to take them alive, then turns his attention back toward the ship. He then adjusts some knobs on his belt and calls for the mysterious TORG to come out -- but the film isn’t ready to reveal him just yet.

Out in the snow, Billy and Betty spot Voldar tracking them and take refuge in a cave. But before he can close in for the kill, the alien hears something and turns to see a (really sad looking) polar bear, which frightens the Martian away first but then goes after the kids -- only the cave proves too small and it can’t get at them. *whew*

Eventually, the guy in the bear suit gives up and moves on. Once it's safe, the kids come out and spot several lights nearby that must be Santa's workshop. But those lights are moving, and getting closer! And then, from out of the snow shuffles TORG, the Martian Robot of Death, who closes in on the frightened children.

For those playing at home, as it comes into the light, we see the Martian Robot of Death is really a refrigerator box painted silver and some heating ducts wrapped in tinfoil for appendages. A few doohickeys are glued to its front, sure, and a bucket is propped on top for a head. And here, we slowly shake our heads, realizing this is the zenith of Martian technology. Now back to the film already in progress!

When TORG seizes the tiny fugitives, Voldar orders it to crush them -- but the robot only obeys Kimar, who sends the kids back to the ship under armed guard. The rest, including TORG, press on to Santa’s workshop, with Voldar still bitching about everything until they reach it.

With orders to retrieve Santa, TORG busts his way inside and starts tossing elves around. (A scene that could’ve gone on for another twenty minutes as far as I was concerned.) But Santa, thinking it’s one of Winky’s new space toys, is intrigued by the giant robot, which inexplicably shuts down as he examines him closer. Yes! The power of Santa has rendered TORG harmless.

Undaunted, when the other Martians burst their way in, Kimar orders Santa to stand down and come with them because he’s needed on Mars. With that declaration, as the elves move to defend the boss, the Martians turn their Freeze Guns on them, much to Santa's distress.

Here, Kimar assures the effect is harmless and will wear off eventually. And when Mrs. Claus comes in and gets blasted, too, Santa knows the old battle-ax will be plenty pissed when she wakes up -- but Kimar says not to worry, they won’t be here when she does…

Make no mistake, Paul Jacobson was an east coast kinda guy.

A one time unit manager for The Howdy Doody Show (1947-1960), this groundbreaking children’s TV series was shot at Rockefeller Center in Jacobson’s native New York, New York. And after working in the high-stakes trenches of live television, when Jacobson decided to make the jump to feature films, he decided to forgo Hollywood and continued to work from the Big Apple.

The Daily Item (October 31, 1964).

“I ran the gamut of TV work,” Jacobson explained to George Cruger (The Daily Item, October 31, 1964). “But I finally decided what I wanted was a chance for independent production.”

After graduating from Tulane University, starting in 1952, Jacobson had spent 10 years in the TV business and covered all facets: advertising sales, management, and production. In 1962, he formed Jalor Productions, which was a nod to his two children, Jason and Laura, and set out to find something to produce and film.

Initially, Jalor’s inaugural feature was to be an adaption of Richard Martin Stern’s hard-boiled detective novel, Cry Havoc, where a private investigator returns to his hometown to bury his late father, only to wind up entangled in a seedy murder mystery involving the sexual assault of a local woman.

Cry Havoc was set to be a co-production with Max Youngstein, who would produce Fail Safe (1964) and Young Billy Young (1969), with an adapted screenplay by Fred Coe, a fellow TV vet, who was also slated to direct.

But as things ground on while the financing for Cry Havoc kept slowly coming together (or falling apart), as the calendar flipped to 1964, Jacobson was having lunch with his friend, Arnold Leeds, in either late February or early March. At the time, it looked like Cry Havoc would finally / maybe go into production sometime in the fall of that year; and here, Leeds suggested that Jacobson should slap something else together; something quick and cheap; something that audiences needed and would be an easy sell.

And what Jacobson decided audiences needed most was a Christmas film targeted specifically at children. As Cruger put it (ibid), Jacobson felt his holiday picture idea would be an innovation, pointing out that most current children’s movies were made in Europe or Mexico and dubbed over in English -- like the ones K. Gordon Murray was making a fortune on with the likes of Santa Claus (1959) and Little Red Riding Hood (1960). And those made in the States, well, Jacobson felt they were not really made for children; and were more aptly termed as “family movies.”

“Except for the Disneys, there's very little in [theaters] that the kids could recognize and claim as their own,” said Jacobson in an interview with Howard Thompson (The New York Times, August 2, 1964). And to fill that void, Jacobson conceived a whopper of a tale, which he described as “a Yuletide science‐fiction fantasy.” Essentially, Santa Claus in outer space.

“I wanted a story with the spirit of Christmas and Santa Claus, but with action and suspense, too. Something for the kids to identify with,” Jacobson told Bernie Bookbinder (Newsday, September 12, 1964). And after a quick trip to the New York Public Library turned up nothing even remotely close to adapting on those lines, Jacobson would end up writing the story himself, telling Bookbinder he wrote it all in less than an hour.

Jacobson’s treatment dealt with Martians kidnapping Santa Claus and taking him back to Mars; not for malicious reasons, necessarily, but to inject some life into their moribund children, whose only joy comes from watching TV shows broadcasted from Earth.

“I wrote three-quarters of the treatment on the train up to Mamaroneck,” said Jacobson (ibid). “I read it to my children as a bedtime story and they reacted very well. That gave me confidence.” And once his children were safely tucked in, with visions of Martians and Santa Claus dancing in their heads, things really snowballed from there.

Within two weeks, Jacobson turned his treatment over to scriptwriter Glenville Mareth to clean it up. In four weeks, he had a finished script ready to shoot. In five weeks, he secured financing, found a studio, got himself a director in Nicholas Webster, and had assembled most of his production crew and selected a cast. And in six weeks, they were shooting. And then, two weeks later, filming officially wrapped on Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (1964) after ten days of shooting.

Not only was the movie made quickly, it was made cheaply,” observed Bookbinder (ibid). “Jacobson declined to say how cheaply, but if Cleopatra (1963) was a blockbuster, Santa Claus Conquers the Martians was a firecracker.”

In that mad two-month scramble to get his (new) inaugural film into production and in the can, Jacobson got most of his financing through private investors. But he scored his biggest coup by finding a distributor with Joseph E. Levine and his Embassy Pictures. And while Jacobson’s motives might’ve been considered altruistic, Levine's end goal was, as always, to make more money.

“Don’t laugh,” reported Philip Scheuer in a blurb for the Los Angeles Times (July 29, 1964). “Somebody really is making a movie with that title, Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, and the omnipresent Joe Levine has a hand in it.”

Joseph E. Levine.

Standing at five-foot-four and weighing in at various tonnages, depending on whether he was crash-dieting or not, the sixty year old Levine was a “portly, lordly multimillionaire motion picture producer,” according to Dick Griffin (Los Angeles Times, June 21, 1966). "[He was also] one of the greatest hucksters of all time … who has introduced many of the best-forgotten movies of the last seven years, as well as a few worth remembering.”

Levine had been a movie theater entrepreneur initially out of Boston, who got into the film distribution business around 1940 to a modicum of success by re-releasing some decrepit westerns and sex hygiene films. But then, he really tapped into something when he started importing some lavish foreign films, dubbing them over, and then blitzkrieged them into theaters with lavish promotions and publicity campaigns.

The Kansas City Star (August 8, 1956).

In 1956, Levine bought the rights for the Japanese film Gojira (1954) for $12,000, spent $100,000 “Americanizing” the film by inserting Raymond Burr, then spent another $400,000 on advertising and brilliantly rebranded the feature as Godzilla: King of the Monsters (1956), which brought in around $2 million at the box-office and officially launched a worldwide phenomenon.

He would do even better with his Italian imports. According to Griffin (ibid), “Levine bought the U.S. rights to Hercules (alias Le Fatiche di Ercole, 1959) for $120,000, swathed it in $1.1 million worth of publicity that covered the nation in a three-week period in 1959 and has so far grossed $20 million.” (For the record, it was more like $5 million, but still!) He would do the same for the sequel, Hercules Unchained (alias Ercole e la regina di Lidia, 1959), and rode that one to even greater box-office success.

“Primarily, I go into all movies to make a profit,” said Levine (ibid). “Obviously we can’t go into a movie if we think we’re going to lose money on it. This is a business.” One of Levine’s most famous quotes was, ''You can fool all the people all the time if the advertising is right.'' Another was, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted, but I could never find out which half.”

And with this guile and brashness, “Levine has helped the tired movie industry relearn how to market its films with smashing success,” said Griffin. “And he seems to fit the Hollywood image of the Hollywood producer, even if he lives in New York.”

When Levine started Embassy Pictures in 1942, the plan was to stick with importing foreign films -- and not just schlock either. He introduced American audiences to Sophia Loren when he imported Two Women (alias La ciociara, 1960), and to Federico Fellini with 8½ (alias Otto e mezzo, 1963); brought in several British action adventure yarns with Zulu (1963) and Sands of the Kalahari (1965); and from Czechoslovakia, the delightful animated features of Karel Zeman with Invention of Destruction (alias Vynález zkázy, 1958).

Domestically, Levine and Embassy backed Edward Dmytryk’s The Carpetbaggers (1964), the saucy biopic Harlow (1965), Henry Hathaway’s Nevada Smith (1966), and a notorious flop with Russell Rouse’s The Oscar (1966). He would also back Mel Brooks’ The Producers (1967) and Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967) and Carnal Knowledge (1971).

When asked by Griffin how he reconciles backing such prestige pictures like those while also financing something like Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, Levine's answer was blunt: “Don’t reconcile them! Why should you have to? I make movies. I just made 15 family-type pictures in 18 months, but don’t let that get around,” said Levine.

“I don’t want anybody to know, ‘cause families don’t go to see them -- they just talk about them. But I made them anyway, because I have the protection of television. Money in the bank, the television.”

Among those family pictures was Bert I. Gordon’s Village of the Giants (1965), a gonzo tale of gargantuan teens and colossal ducks; the Rankin and Bass animated features The Day Dreamer (1966), and one of my personal favorites, Mad Monster Party? (1967); and, of course, Jacobson’s Yuletide outer-space adventure, which continues on as Kimar’s ship rockets back to Mars with his three abductees.

Meanwhile, word breaks that the Martians have kidnapped Santa as new reports flash across the globe, saying the United Nations was burning the midnight oil to get Santa back. (All together now: Give sanctions more time!) But all of this might prove unnecessary.

For you see, back on the Martian ship, with an odd combination of Christmas Carols and lame jokes, the mere presence of Santa is already having a strange, mollifying effect on his captors. Seeing this as the beginning of the end of Martian life as he once knew it, Voldar fumes and schemes to put a stop to this menace (before they're all turned into "Martianmellows") once and for all.

In the brig, feeling guilty that they led the Martians right to him (-- that’s because you did), the kids need some cheering up. Here, Santa says not to worry, insisting he always wanted to visit Mars anyway. But when Droppo brings them dinner -- a three-course meal, condensed and concentrated into several small pills -- the general consensus of the Earth kids, so far, is that Mars kinda sucks.

Later, Voldar pays a visit and, with an apparent change of heart, wants to give them a more extensive tour of the ship -- and I say ‘apparent’ because this tour will begin at the airlock. [Ackbar/ “It’s a twap!” [/Ackbar]. And while Billy and Betty don’t trust him, Santa believes everyone deserves a chance, even a stinker like Voldar, who escorts them right into the airlock.

Here, Santa is proved fallible when Voldar sneaks off as Billy explains to Betty and Santa what an airlock is for. He then throws a switch, sealing the Earthlings on the wrong side of the inner hatch! As the kids panic, Santa says not to worry.

Meanwhile, Voldar throws another switch, the outer airlock hatch opens up, and whatever was inside gets sucked into space! Alas, Kimar arrives too late to stop this; but as they brawl around they're interrupted by a familiar laugh. Then, Santa, Billy and Betty round a corner, safe and sound.

Voldar can’t believe they’ve escaped; the only way out was a tiny air duct -- no bigger than a chimney flue, you might say. (Wink. Wink. Nose Nudge.) Here, a pragmatic Santa assures Kimar what Voldar did was just an accident. Accident or not, the dastardly Martian will have plenty of time to contemplate what he did and how they escaped while confined to the brig. (Behold the power of Santa, you green moron!)

Well, beyond that near death experience, the rest of this intergalactic voyage proves relatively uneventful. But after they land, they find Droppo tied up in the brig, meaning Voldar has escaped. And knowing he’ll be back to cause more trouble, Kimar orders a 24-hour guard on Santa and the children. But that’s a worry for later; for now, the children of Mars are waiting.

Taking them to his home unit, Kimar first head-butts his wife (-- I think this is a standard Martian greeting), and then introduces the Earth children, who get head-butts of their own. Then, Santa makes his grand entrance and apologizes for his bombastic behavior. Seems he’s not used to coming in through the door since Martian houses have no chimneys. (Ho-ho-oh-no. He’s got a million of them, folks, and unfortunately, we’ll get to hear every one of ‘em.)

The Earth troupe is then marched over to meet Kimar's kids, and it isn’t long before Santa has the stoic Martian children cackling like idiots. So pleased by this is Kimar he quickly takes Santa aside and reveals his grand plan to build him a factory to produce all kinds of toys. That's a swell idea, says Santa, who agrees to do all he can to get it up and running so he can return to Earth in time for Christmas.

Here, Kimar solemnly breaks the bad news that, no, he will not be returned to Earth but will remain on Mars (Dahn! Dahn! Dahn!) forever.

Meanwhile, Voldar and his two stooges, Stobbo and Shim (Nesor, Elic), hide out in a cave and conspire to bring Kimar and Santa down. But Shim thinks this is impossible because Santa is too well guarded. Stobbo has even seen the new toyshop and was mesmerized by the fantastical products. But that’s the key, says Voldar. For there are other ways to get at Santa, like discredit him -- and turn him into a laughingstock -- by sabotaging the factory.

At said factory, Santa is quickly growing bored with the pushing of the automated buttons. See, all he has to do now is hit the right switch and the Martian machines will regurgitate the desired toy onto a handy conveyor belt for further distribution, with Billy, Bomar, Droppo and Girmar collecting the toys while Betty reads Santa the wish lists.

Deciding to call it a day, Santa shuts down the equipment. As they head out, he picks up a spare suit that Momar made for him. When Droppo asks if he can try it on, Santa ribs him, saying he’ll have to put on a little more weight first.

Back at Kimar’s for the night, Santa complains about his finger being tired and heads straight to bed. The Martian kids, meanwhile, ask if they can watch some Earth TV before they hit the hover-sack. Kimar gives them permission but notices Billy and Betty aren't all that interested. In fact, they're acting pretty glum.

Asked if they’ve been mistreated, the Earth kids say no; they’ve been treated really well. Thus, Kimar doesn’t understand what the problem is, but Momar sure does: the kids are homesick, and she begs Kimar to take them back to Earth. But Kimar says that’s impossible.

As they argue, Droppo steals that spare Santa suit and starts bogarting food pills, trying to gain the necessary weight. He then tries the suit on, but is still too scrawny.

Here, he gives up on the pills and just uses a pillow as stuffing to fill it out. He also finds a spare, plot-convenient Santa beard lying around to complete the ensemble. With that, he excitedly decides to return to the factory and make more toys.

Meanwhile, back at the toy factory, Voldar and his gang have already broken in and thrown a monkey wrench into the mechanisms. When they hear someone approaching they kill the lights and hide. In the dark, they look past the green face and antennae and mistake Droppo for Santa.

At this juncture, I don’t think I need to point out that all Martians are morons, so this stretch of the plot isn’t that big of a stretch if you think about it as Voldar hauls his prisoner back to their hideout. And after securing his prisoner behind a nuclear curtain, Voldar exclaims that with Santa out of the way Mars will now return to normal.

The next morning, Momar can’t find Droppo and Santa can’t find his extra suit. Quickly putting two and two together, they realize when they find one they will most likely find the other.

Santa also correctly assumes Droppo went back to the toy factory. But Droppo isn’t there. Not to worry, Santa assures as he cranks up the machine, their friend will show up eventually. But as the machine rumbles to life, it starts spitting out mutant toys! (Charlie in the Boxes, trains with square wheels, cowboys riding ostriches etc.)

Told to call Kimar, Bomar tunes his father in with his antennae. When he arrives they discover the switched circuits and figure only Voldar could be behind this dubiousness. And to make matters worse, Santa’s convinced that Voldar has Martian-napped a disguised Droppo, mistaking him for the real thing.

With that, Kimar promises to find Droppo and departs -- only to run right into Voldar, who claims to have Santa as a prisoner and demands the factory be shut down immediately -- or else! Think again, Kimar says, opening the factory door, revealing the real Santa safe inside.

With that, Kimar draws his Freeze Gun and herds the bad guys into a storage closet and moves to call the police over his internal radio. Meanwhile, Droppo has, somehow, miraculously managed to engineer his escape without disintegrating himself.

But back at the factory, Voldar and Stobbo manage to overpower Kimar, knock him out, and take his weapon. And after cranking the Freeze Gun up to the highest setting, Voldar declares he’s tired of playing around and will now remove Santa Claus -- permanently.

Luckily, Billy overheard all this and warns Santa, who decides it’s time to teach Voldar a lesson by putting him on the naughty list -- permanently.

Thus and so, as the kids set up an ambush, Voldar breaks in and gets pummeled by several volleys of toys. What follows next is a rather embarrassingly long assault and vintage toy commercial, as Voldar is bopped and splattered into submission. Then the Martian police finally arrive and drag Voldar off to jail.

With that crisis in the can, Santa tells Kimar that Mars doesn’t need him anymore for they have their very own Santa, and then points to Droppo. Kimar happily agrees and they all share a laugh.

And so, the Martians say goodbye to the Earthlings as they board the Tinker Toy and rocket back to Earth.

And thus began the reign of Droppo, the First Martian Claus; and he ruled all the lands with a benevolent -- if not spastic -- hand. And there was much rejoicing, which brings us to...

Filming on Santa Claus Conquers the Martians took place between July 27 and August 7, 1964, at the Michael Myerberg Studios, which were three converted airplane hangers located on Long Island’s Roosevelt Field just outside of Garden City, New York.

“At this particular studio, with a group of wonderfully cooperative technicians, we’ve been able to get a lot of production value from our low budget,” said Jacobson (Thompson, 1964). “We’re also shooting in color to get full, picturesque effects with our toy factories, and Martian and North Pole backgrounds.”

Though a tightly held secret, it's believed the total budget for the film was around $200,000. And if you’ve seen the film, which appears to be slapped and dashed within an inch of its life, you might be scratching your heads a bit as to where any of that money went? Still, I think the film managed to overcome this adversity and found the perfect balance between being, as one person a lot smarter than I rightfully noted, "incredibly enjoyable, yet hopelessly inept."

To help maximize those minimal dollars, Jacobson appointed his friend Leeds, another TV vet, as his associate producer and production manager. Most of the crew were culled from their TV contacts, and most of the props and decorations were cannibalized from other local productions.

“Instead of money we used ingenuity,” said Leeds (Bookbinder, 1964). “We shot this in TV fashion. You know, on live TV we had to get it right the first time.”

As Leeds gave Bookbinder a tour of the cluttered sets back in ‘64, he

pointed out “a colorful mechanical-looking contraption in the antiseptic

workshop” the Martians constructed for Santa. “That was rented from a

TV studio,” said Leeds. “It was part of a giant clarinet used as a

backdrop in a spectacular. The workshop control panel came from the Fail

Safe movie set (-- making me believe that Youngstein was one of those

silent backers on the film). And the nose of that Martian spaceship was

the ceiling of a nightclub in a chewing gum commercial.” (All pictured directly above.)

And art director Maurice Gordon pointed out several papier-mache rocks. “We borrowed those from [another TV program], said Gordon. “We painted them green and used them for an outdoor scene, we painted them white for the North Pole, and we painted them red for Mars. Upside down and white they were a polar crevasse, and upside down and red they were a Martian cave.”

Edward Swanson was in charge of building the sets, Frank Hoch handled

the winter and alien backdrops, and Jack Wright was in charge of props,

making him responsible for TORG, who, as far as cardboard and trash-can

robots go, was kind of adorable. Gene Lindsey portrayed both TORG and

the unfortunate looking polar bear.

What their efforts brought to mind the most were the minimalist approach of William Cameron Menzies' Invaders from Mars (1953) and the colored gels and the kit-bashing, found art of Mario Bava's forthcoming Planet of the Vampires (alias Terrore nello spazio,1965), which was then mashed into the absurdity of Dr. Seuss.

Meanwhile, Fritz Hansen (settings) and Virginia Schreiber (wardrobe) were charged with developing the Martian’s overall aesthetic. “In this picture, everything dealing with Mars had to be different but recognizable,” Gordon told Bookbinder. “We gave the Martians round beds with cube-shaped pillows, for example.”

It was also a complete no-brainer to make their Martians green. Said Gordon, “Well, it's a Christmas color, particularly alongside Santa’s red suit. And then, people tend to think of those from outer space as ‘little green men.’”

The Martian custumes [sic] consisted mostly of green greasepaint, green turtlenecks, pixie boots, and skin-tight leotards, which showed all kinds of bulges in all the wrong places. This ensemble was then completed with a Martian utility belt and a helmet adorned with several kitchen utensils and natural gas pipings and fittings.

Also of note, the Martian's main weapon, the deadly Freeze Guns, were simply Wham-O Air Blasters. The notorious Air Blaster, which came out in 1962, was a big hit and relatively harmless. You cocked the gun, pulled the trigger, and the trapped air would pop out the barrel.

However, when kids started stuffing the barrels full of things -- nails, glass, molten lava -- and shot them out under the same compressed air, thousands of children were maimed and killed -- or so Consumer Product Safety groups would have you believe. (Friggin' Toy Nazis.) Feh. Also of note, the larger weapon seen briefly in Santa's toyshop appears to also be a converted toy painted black: The Johnny Seven O.M.A. (One Man Army) rifle.

In a later interview with Harry Medved for his book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time, Jacobson related how “the people working on a film make or break a picture budget-wise. Everyone knew from the very beginning we had a low-budget film and that they would have to be satisfied with scale payments and no overtime,” said Jacobson. Who was also happy to report, “There was not a single problem created by the crews.”

Jacobson also struck a deal with Louis Marx and the New York based Marx Toy Company, who provided the majority of the toys in Santa’s Martian workshop, which would explain several lingering shots on some of their wonderful toys during the climactic fight. (Marx made the best playsets back in the day: Battleground, Navarone, Comanche Pass, Fort Apache etc.) Not to mention a backdoor commercial for the resurgent Slinky as the Martians marvel over it -- in case you were thinking blatant product placement was a more recent odious development.

Trying to make all of this jive from the director’s chair was Nicholas Webster. Webster came from the world of news programs and TV documentaries, lensing Walk in My Shoes (ABC News Closeup, 1961) and The Violent World of Sam Huff (The Twentieth Century, 1961), and had just come off his first feature film, Gone Are the Days! (1963), where he teamed up with Ossie Davis on a comical social satire about race and a good old fashioned land swindle. And later, Webster would also direct one of my favorite cryptid docs of the 1970s with Manbeast! Myth or Monster (1978).

“We’ve been shooting about four takes for everyone we use,” Webster told Bookbinder, in reference to keeping the budget down. “That’s a very low ratio. Sometimes it can run 15 or 20 to one.”

And while it took a bit of an adjustment, going from helming programs on “epilepsy, famine, and racial tension” to children’s fare, Webster enjoyed the change of pace. “It’s a pleasure to be doing something noncontroversial and happy,” said Webster (Bookbinder, 1964). “It’s all part of the same business. You know, this isn’t any different than Hollywood.”

As for the cast, some were local TV talent, but most were recruited from Broadway or Off-Broadway -- though from well down the cast lists. Victor Stiles (Billy Foster) was one of Fagin’s pickpockets in the current run of Oliver!, where he was also the lead understudy. And Donna Conforti (Betty Foster), was plucked from the children’s chorus of the musical Christmas frolic, Here’s Love.

Playing the Martians, aside from a bit part in an episode of Route 66 (S04.E15, 1964), Kimar, the Martian leader, would be Leonard Hicks’ only screen appearance. His wife, Momar, was played by Lelia Martin, another theatrical vet. And according to a very reliable source, the actress was still in the game as of 1999, playing Madame Giry in Andrew Lloyd Webber's Phantom of the Opera -- and not only that, but Martin touted her role in Santa Claus Conquers the Martians in her bio for the show's Playbill, which I find to be incredibly cool.

As the villainous Voldar, Vincent Beck would have a solid career playing heavies on episodic TV. And for the longest time, I thought Voldar’s chief henchman, Stobbo, was played by Jamie Farr but, nope. That was Al Nesor, who also played Evil Eye Fleagle, another kooky character in the cinematic adaptation of Lil’ Abner (1959), who everyone also mistakes as being Farr.

In his role as the comedy relief, Bill McCutcheon plays well to his juvenile audience -- though it will probably grate on the adults in the room. And McCutcheon would continue with his Droppo shtick as Uncle Wally on Sesame Street from 1984 until 1998.

Santa Claus Conquers the Martians would also be a one and done for Chris Month, but, of course, everyone knows his Martian sister was played by Pia Zadora, making her big screen debut.

As the old (and rather tasteless) joke goes, when it was rumored that Zadora would be cast in a revival of The Diary of Anne Frank in the 1980s, people feared audiences would let the Nazis know where they were hiding by chanting "She's in the attic! She's in the attic!" as a rather scathing indictment of her acting prowess.

She would star in a string of notorious films in the early 1980s, Butterfly (1981), Fake-Out (1982) and The Lonely Lady (1983). She would win the Golden Globe for New Star of the Year for her role in Butterfly, even though she technically made her debut 17 years earlier. Rumor had it that her then husband, Meshulam Riklis, spread some money around and "bought" her that award.

This controversy raised such a stink that the Hollywood Foreign Press Association retired the category the very next year. The scandal also pretty much torpedoed Zadora’s attempt at reviving her acting career, relegating her to roles in things like Pajama Tops (1983) and Voyage of the Rock Aliens (1984).

Which brings us to John Call, who played our title character. Call was also part of that revival of Oliver! and had already appeared in several other features -- most of them uncredited, including a bellboy in Don’t Bother to Knock (1952) and as a reporter in The Pride of St. Louis (1952). His most notable role, aside from Santa, was also his last, playing O’Leary the doorman in the crime caper, The Anderson Tapes (1971).

As the centerpiece of Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, Call takes the role and runs away with it, cackling the whole way. He makes a pretty good Santa, despite what the script calls on him to do, with plenty of scenes where his laughing and cackling kinda come off as sinister and menacing, when they’re supposed to be jolly, making him more of a creepy uncle instead of a jolly saint. (Again, it appears Santa has been hitting the Christmas punch a little too much.)

And then there’s the disturbing scene when he’s complaining about his tired finger and points it around and shows it to everyone -- like some rogue proctologist. Eek.

Speaking of musicals, Milton Delugg composed that infectious title song and the rest of the wild soundtrack. Now, Delugg had served as bandleader for The Tonight Show when Jack Paar was the host. But he was replaced by Doc Severnson after Johnny Carson took over. However, Delugg went on to be the bandleader for Chuck Barris’ The Gong Show -- cranking up Count Basie's “Five O'Clock Jump” whenever Gene Gene the Dancing Machine took the stage.

And as part of Levine’s publicity blitz, a 45-record of "Hooray for Santa Claus" by Delugg and the Little Eskimos was released. And a storybook LP, which also included the Dell Comics adaptation of the film, also hit the shelves. Both are highly collectible. That same year, trumpeter Al Hirt would release a cover of the title tune.

After filming wrapped, Santa Claus Conquers the Martians would spend another six weeks in post-production as the film was edited and scored. Jacobson had hoped the film would be finished in time to deliver it to Levine for his birthday in early September, but several delays scotched this.

But the film was ready to roll for the Holiday season, and was released on November 14, 1964, in Illinois and Michigan, where it played exclusively on weekend matinees; and critical reaction was surprisingly even-handed, recognizing the film for accomplishing what it set out to do.

The Daily News (December 28, 1964).

“Santa Claus is paying an early visit to our town,” advised Mae Tinee for the Chicago Tribune (November 8, 1964). “And his brief presence will be a boon to parents in search of suitable entertainment for young children. It is not a cartoon or a short subject but a full-length story about envious Martians who zoom down here and kidnap Santa Claus. There are ray-guns and robots, and I’m sure space-minded modern children will enjoy this cheerful little fantasy.”

Meanwhile, “The new tale about the jolly old elf drew capacity crowds and satisfied the youngsters almost entirely,” reported Joan Vadeboncoeur in her review for the Syracuse Herald-Journal (November 15, 1965). “There is nothing like Santa Claus and Martians to attract and delight the young set. The plot is corny but packs enough action and suspense, plus a few laughs, to keep the children happy. And it's produced with no eye to the budget. The sets reflect imagination and money.”

Newsday (September 12, 1964).

But Levine’s four-wall campaigning also stirred up some controversy, as reported in the Akron Beacon Journal (November 24, 1964): “When movie houses in Chicago booked a bizarre film titled Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, they touched off a storm of TV commercials plugging the film. Children saw Santa being kidnapped by Martians and swamped the stations with worried calls. Two stations [reportedly] canceled the commercials immediately.”

But the controversy did little to stop audiences from attending, as Dorothy Kilgallen reported in her column (November 27, 1964), “Joe Levine’s newest success story is a kiddie picture called Santa Claus Conquers the Martians. It just opened in Chicago -- in a mere 100 theaters -- and in three days did $120,000 on matinees alone. The flick was made in New York in 10 days for peanuts, and as a result of its hit, the producer, Paul Jacobson, has been signed by Levine for 13 more features.”

The Streator Times (October 31, 1964).

As far as I know, nothing ever came of Cry Havoc, but I do know Fred Coe had a nice consolation prize directing A Thousand Clowns (1965) instead, which earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture. Another proposed title I found digging around on Jalor’s slate was an adaptation of Stuart Hood’s Pebbles in My Skull, an autobiographical tale about a British intelligence officer’s escape from a German prisoner of war camp.

According to a blurb in The Morning Call (August 24, 1965), Levine and Jacobson had come to terms on three films (not 13) set to be produced in 1966 under the Jalor Productions banner and released by Embassy. “Described as psychological suspense thrillers, the projects, all tentatively titled, are The Mahopac Story, The Chill and the Kill, and The Laughter Trap.”

Early details showed The Mahopac Story concerned a teenager who was committed to a mental institution against his will, who escapes after witnessing a murder for which he is blamed. The Chill and the Kill was to be about a teenage girl who comes out of a terrible auto accident with clairvoyant powers, who is stalked by a killer who fears she will use her new skills to identify them. And The Laughter Trap involves another auto accident and the sole survivor tracking down the thrill-killers who caused it.

Now, if none of these films sound familiar to you, don’t sweat it. That’s because none of them exist because they were never made. In fact, as far as I can tell, Santa Claus Conquers the Martians was Jacobson and Jalor Production’s sole output. I have no idea what happened or why the bottom fell out, believe me, I tried. And if it’s any consolation to Jacobson, his one and only film stayed in circulation during the holiday season well into the 1970s.

The Mansfield News Journal (November 4, 1965).

There were rumors back in the late 1990s that the Zucker Brothers -- Airplane! (1980, The Naked Gun (1988) -- were interested in doing a remake of Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, and Jim Carrey was attached to play Droppo. But the rumor ends with Variety (February 1, 1998) reporting the project being stuck in development hell and hasn’t been heard from since.

But as far as legacies go, Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, by no means a great film, is nowhere near as bad as its dubious reputation. As mentioned before, it made the Medved’s list as one of the worst films of all time but, like a lot of films listed in that dubious tome, its inclusion was based not on content but the gonzo title alone.

And in conclusion, Fellow Programs, though not quite the holiday staple on the level of It’s A Wonderful Life (1946) or A Christmas Story (1983) or even Black Christmas (1974), Santa Claus Conquers the Martians has carved it’s very own and well deserved niche in Christmas viewing lunacy.

I’m sure we’ve all seen worse, and I think its heart was definitely in the right place all along. And let's give the film some credit because it uses that sincerity to its advantage, and could even be read as an anti-technology screed hidden inside those juvenile trappings, raising itself several notches above one of the worst films of all time.

Originally posted on May 29, 2002, at 3B Theater.

Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (1964) Jalor Productions :: Embassy Pictures Corporation / EP: Joseph E. Levine / P: Paul L. Jacobson / AP: Arnold Leeds / D: Nicholas Webster / W: Glenville Mareth, Paul L. Jacobson / C: David L. Quaid / E: William Henry / M: Milton Delugg / S: John Call, Leonard Hicks, Vincent Beck, Bill McCutcheon, Victor Stiles, Donna Conforti, Pia Zadora, Lelia Martin, Ned Wertimer, Doris Rich, Carl Don, Al Nesor, Josip Elic

No comments:

Post a Comment