"We live."

I remember first watching Bug (1975) when I was, like, eleven or twelve, a movie of the week; and I remember it fah-reaking the hell out of me, which had me anxious to give it another spin, prodded on by others asking for memorable films about creepy-crawlies. And I knew I had a copy, somewhere, having bought the DVD when it was released back in 2004, but, turns out, I had never even removed the plastic wrap until I watched it for this review over ten years later.

Guess there was some residual freak-out still lingering. Mebbe. Whatever. Wait. Why is my leg suddenly itching...

Anyways, the film was based on the Thomas Page novel, The Hephaestus Plague, which was set in the fruit and tobacco belt down south. It kicks off with a massive earthquake that opens up a near bottomless, several-counties long chasm, which disgorges thousands of large, beetle-like insects.

Armored like a mini-Sherman tank, making them nearly impossible to squish, and filled with a strange symbiotic bacteria instead of the usual internal organs, this new breed of pesticide-resistant bug were also equipped with a special set of rear antennae, which when rubbed together, spark like two pieces of flint, burning everything it comes into contact with and reducing everything around them to carbonized ash; the only thing these critters will eat.

And so, like a slow but relentless plague of highly flammable locusts, these firebugs start wreaking all kinds of havoc with the local farmers. And once these bugs start hitching a ride on passing automobiles, what once was an isolated problem soon becomes a nationwide epidemic.

Enter entomologist James Parmiter, a pompous, unlikable lout, whose morbid fascination with all things that creep and crawl give him the insight needed to classify and find this new species of bugs' vulnerabilities, which he names Hephaestus parmitera, putting himself in the same league as the Greek god of fire.

Labeling them as an offshoot of the common cockroach, Parmiter deduces that the reason these bugs are so slow and dense is because they come from deep beneath the Earth's crust, where they were under considerable atmospheric pressure; and now, basically, they're suffering from a case of the bends.

Things get a little weird from there as the obsessed Parmiter -- some might even call him ... mad -- has no intention of destroying these bugs but instead starts to crossbreed them with regular roaches, creating a new strain; a new strain that can communicate with him!

It's been awhile since I'd read Page's novel, as well -- I vaguely recall reading it not long after I saw the movie, finding one of those "Now a Major Motion-Picture' tie-ins at some broken spine; and the only thing I really remember about it was the hair-brained efforts to find a natural predator for the firebugs. A tarantula's venom proves worthless, and a centipede is no match and quickly shredded. But the one test I recall vividly is the Gila Monster, which ate one of the bugs only to have it burn itself back out through its stomach.

The film adaptation of The Hephaestus Plague alludes to this scene at the beginning, when a family farm-cat has a similar fatal encounter with several of the bugs; the first of many gruesome and prolonged casualties -- especially if you're a feline, or blonde and pretty and female.

William Castle (Left).

After establishing a reputation as the low-rent master of fright, William Castle had unleashed over a decade's worth of gimmick-driven films; and at the zenith of his popularity, the man's personal fan club had nearly a quarter of a million card-carrying members.

But after introducing the world to Percepto -- The Tingler (1959), Emergo -- House on Haunted Hill (1959), Illusion-O -- 13 Ghosts (1960), and the Fright Break -- Homicidal (1961), the producer / director seemed to achieve a paradigm-shift in his career when he secured the rights to Ira Levin's Rosemary's Baby, which he leveraged into a deal with Paramount, who would let him produce the film but under no circumstances direct it.

Unfortunately, this shift stalled when bad health kinda derailed things after Rosemary's Baby (1968) proved a box-office bonanza. His next film, Project-X (1968), was a disaster, and his personal art-project, Shanks (1974), which was better than you've heard, failed to find an audience. And with Paramount's patience at an end, in an effort to get his groove back, Castle decided to return to his roots and make another gimmick-driven horror movie.

The 1970s saw a brief resurgence in "mad science" monster movies and creature features. Some were pretty great -- Phase IV (1974), some will surprise you by how good they were -- Sssssss (1973), some were hilarious -- Night of the Lepus (1972), and some were pretty awful -- Food of the Gods (1976), and then there's Bug, which was kind of a combination of all the above.

Again, Castle would only produce Bug, leaving the directing to Jeannot Szwarc, who, for a brief -- and I mean, brief, period of time, was pegged to rival Steven Spielberg as the best of the new young Turks of Hollywood in the 1970s. I've never been a big fan of Szwarc myself, finding his films flat, lifeless, and dull-looking. Perfunctory. I've never seen someone who can make cinema on some of his budgets -- Supergirl (1984) and Santa Claus (1985), look like cheap, cash-in Made for TV movies.

Now, Bug didn't have that kind of money, but the director still managed to pull the effect off. *sigh* In his defense, I guess he was really good at that?

During pre-production, Castle had also wanted to bring back some of his old-school ballyhoo by installing automatic brushes under theater seats, which would activate and tickle the audiences' ankles at certain strategic points to induce a case of the screamin' heebie-jeebies. This was deemed not cost-effective by the studio and nixed. There was also an attempt to strike a deal to give away free cans of insecticide to moviegoers that was also nixed -- most likely for health and safety reasons.

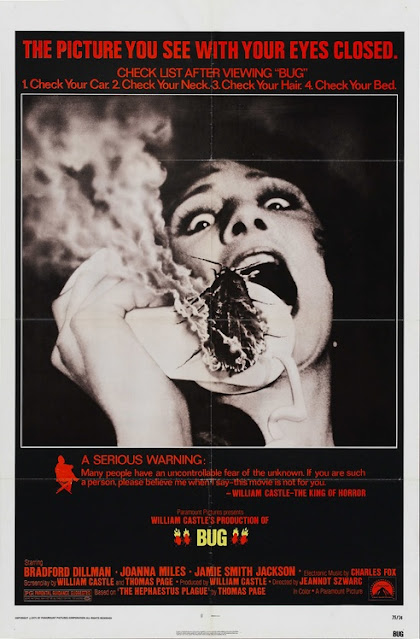

Undaunted, Castle still embarked on a personal cross-country promotional tour with "Hercules," one of the giant cockroaches used in the film, which Castle took out an enormous life insurance policy on. The promotional materials also carried the usual Castle hucksterism with a Serious Warning from the producer: “Many people have an uncontrollable fear of the unknown. If you are such a person, please believe me when I say -- this movie is not for you.” I also loved the tagline from the trailer, "You won't live alone -- if you live at all, when the Bug comes to your house."

As for the actual film, aside from moving the action to southern California, their adaptation doesn't stray too far from the source novel (-- in fact, Page co-wrote it with Castle), with one notable and sizable exception: Page's Parmiter was a bachelor, who had turned his back on humanity long before the earth had broken open and belched-up his new best friends. One could almost consider him a co-conspirator of sorts.

But Szwarc's Parmiter, played brilliantly by Bradford Dillman, was very different. A little too caught up in his work perhaps, a little too target-fixated, but still a good man trying to solve a potentially epoch-level problem only no one will listen to him or pay attention to his findings.

And what I remembered most about that initial screening wasn't the killer bugs, but the “mad” scientist slowly cracking up and making some horrific decisions; essentially one very sick man dooming humanity by adapting the "Bugs From the Earth's Core" to breathe and breed topside. This is what kept me up that night, not the giant cock-a-roaches. Though they were pretty gross.

See, it all falls apart for Parmiter when a careless oversight on his part results in the tragic immolation death of his wife, Carrie (Miles), and the destruction of their home. Sharp eyes will notice the interior is the recycled kitchen, family room, and den from the recently canceled TV-series, The Brady Bunch (1969-1974). And even not-so-sharp eyes will spot Joanna Miles' obvious stunt-double.

Joanna Miles:

Not Joanna Miles:

Apparently, Miles was “deathly afraid” of the insects used in the film -- which averaged between four and five inches in length, and initially refused to let any of them crawl on her. There’s an apocryphal story that Castle tried to demonstrate how harmless they were by having one crawl on his arm but was subsequently bitten, which is relatively harmless unless there’s some kind of allergic reaction -- according to Professor Google, at least. Either way, I’m sure this didn’t help the cause.

Miles’ protest was joined by her co-star, Jamie Smith Jackson -- that’s her in the promotional materials having a close encounter with a Hephaestus parmitera while on the phone, a fate her character shares in the film, where one of the critters crawls into her ear before sparking off, who almost pulled out of the film when told she would have to “get chummy” with hundreds of the creeping and crawling roaches.

The Fort Lauderdale News, September 6, 1974

Said Castle in an interview with Vernon Scott for the UPI (The White Plains Journal-News, September 5, 1974), “They spent three days in the photography lab learning how to handle the bugs. The first day they wanted to quit. On the second they became more secure with the roaches. By the third day they allowed the bugs to crawl all over them. But the girls still aren’t fond of cockroaches.”

And after the lethal bugs pick-off all the ladies in his life, Parmiter holes up in an isolated farmhouse with a pressurized tank, determined to crack and break the bugs to his will in several scenes that can best be described as insect torture porn or a roach atrocity film. And while his method of cross-breeding a newer and even deadlier strain seems completely illogical to the viewer, it's completely logical to him.

That's what I mean by scary. That right there. And as a third generation of firebugs gestate, and a psychic hive-mind link is established between man and insect, it becomes crystal clear as to who is really controlling whom.

Dillman's big break seemed to come early in his career when he played one half of Leopold and Loeb in Compulsion (1959), based on the notorious true-crime case and the resulting trial. But things kinda sputtered from there, which was bad for him but great for schlock cinema fans everywhere because he wound up in things like this, The Swarm (1978), Piranha (1978), and Guyana: Cult of the Damned (1979), adding a metric-ton of gravitas.

I have never encountered a more intriguing and pathetic crackpot scientist than James Parmiter; mostly because his efforts were based on emotional damage instead of the usual narcissism. He truly is insane. And in anyone else's hands, I fear the character would've been a disaster.

Now, if you read up on Bug the general consensus is: it's pretty good but drags in the middle. On that I will disagree, because the middle is about 80% wild-eyed and twitchy Dillman taking a long walk off a very short sanity pier, and then the other 20% is poor Patty McCormack getting eaten alive.

No, where Bug ultimately fails is in the climax; and that's completely due to a grievous misstep and several tactical blunders by the FX department.

Up 'til the end, the bugs in Bug were played by a succession of real insects wrangled and shot by Ken Middleham with a macro lens to great effect, starting with the Blaberus giganteus alias the Central American giant cave cockroach as the first generation (-- the males look like freakin' trilobites), the Madagascar hissing cockroach as the second, and the Palmetto bug as the last incarnation.

Palmetto bugs, of course, can fly, and when they burst out of the chasm, the superimposition looks a little cheesy but it works. Sort of. Unfortunately, Dillman has learned too late that he's made a grievous error in judgment (-- actually about six or seven of them), and is soon swarmed over by a bunch of plastic, off-the-shelf toys that no amount of quick-cut editing will make you ignore the very visible strings they're hanging from, nearly torpedoing all the creepy and icky mental decay that had been happening for the previous hour and change.

Others may be more forgiving for such compromises, and they are endearing to a point -- and bring to mind the flying cruller monsters from It Conquered the World (1956). And if this film had been in the same gonzo vein as, say, Night of the Lepus, it would've been fine and more forgivable -- even applauded, but the film was a little more ambitious than that, I fear.

And then Bug just kinda ends, with a fire-engulfed Parmiter cannonballing into the chasm, with his "children" swarming in after him, followed by what can only be quantified as a Divinely-timed aftershock that seals the breach before the end credits roll and Charles Fox's eerie electronic score plays us out.

Well, crap. Until the last five minutes, Bug was as eerily effective as I’d remembered -- better than I'd remembered, actually, but is ultimately skewered by this digital age that isn't as forgiving as broadcast TV on a 12-inch screen was way back when.

“People love horror films for the same reason they ride roller coasters,” Castle told Scott. “It’s exciting but not dangerous. It’s an emotional release for audiences who enjoy laughing at themselves for being scared. This film will end all horror and catastrophe pictures. It looks so good I tried to buy it from Paramount but they wouldn’t let me. It will petrify the audience.”

Paramount, of course, would regret that decision as Bug also failed to find an audience. And I’m sure it didn't help, and to add insult to injury, that the film had the misfortune of premiering the exact same day as JAWS back in 1975, a big-budgeted B-picture that Castle and others of his ilk used to churn out almost weekly from 1955 through 1974 -- in fact, I'd argue that Castle had already done this with Rosemary's Baby, and Bug got absolutely crushed at the box-office.

The Grand Island Independent, September 19, 1975.

Sadly, this would be Castle's last film. After that string of box-office failures post-Rosemary’s Baby, Paramount happily let him go. But Castle immediately signed a multi-picture contract with 20th Century Fox and set to work on an adaptation of Diana Ramsay’s The Dark Descends, a “chilling urban horror story.” Alas, this never came to fruition as Castle would suffer a fatal heart attack in 1977.

Somewhat ironically, Szwarc's next project would be directing the sequel, JAWS 2 (1978), which, true to form, also looks like a Made for TV cash-in of the original. I touched on this in several earlier reviews on how Szwarc seemed to fizzle theatrically but thrived working in television with several crackerjack telefilms and some great Night Gallery (1970-1973) episodes, which, thinking on it, Bug might’ve made a great episode of.

Regardless, even though it tripped over the finish line and fell in a very deep hole, I'd still give Bug a hearty recommendation. Watching Dillman work makes it worth a spin alone, the firebugs are just set-dressing. Nightmare inducing set-dressings, sure, because, I mean, *bleaugh* -- AND, DAMMIT, WHY ARE MY LEGS STILL ITCHING!?!

Originally published on June 16, 2015, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

Bug (1975) William Castle Productions :: Paramount Pictures / P: William Castle / D: Jeannot Szwarc / W: William Castle, Thomas Page (novel)/ C: Michel Hugo / E: Allan Jacobs / M: Charles Fox / S: Bradford Dillman, Joanna Miles, Richard Gilliland, Jamie Smith-Jackson, Alan Fudge, Jesse Vint, Patty McCormack

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment