"But what are they?"

Our film opens at a small private airport, where a young woman is just finishing up her pre-flight checklist before taking her single-engine Cessna out for a solo joyride over the wooded Pacific Northwest. But not long after takeoff, her plane develops a fatal engine hiccup and is soon falling from the sky.

Forced to bail out, Joy Landis (Lansing) dons her parachute and abandons the plane, which plummets to the earth and crashes somewhere cheaply and efficiently off-screen. Meanwhile, the pilot manages to land safely in a clearing, skins herself out of her flight suit, revealing some kind of form-fitting, split-to-the-nethers Star Trek-esque onesie underneath, complete with miniskirt. But she barely has time to tend her scuffed knee and get the lay of the land before something big stalks out of the trees -- something not quite human judging by the guttural noises it makes and the hairy legs framing the screen, which close in on the woman, who recoils in terror and screams as we fade to black.

Meantime, before you can even say, “This was no Bear Attack!”, not all that far from where Joy's plane went down, two traveling salesmen/con-artists are also having to make an emergency landing when their old station-wagon overheats on a long and winding stretch of mountain road. Here, the younger of the two, Elmer Briggs (Mitchum), heads off into the brush to fetch some water out of a nearby creek to satiate the boiling radiator, leaving his partner, Jasper P. Hawks (Carradine), loitering behind, where he is nearly run over by a passing gang of motorcycle-riding hooligans -- albeit the best dressed and most clean-cut band of motorcycle-riding hooligans that I've ever seen committed to film.

Anyhoo, over at the creek, Briggs stumbles upon some strange animal tracks in the soft loam along the water's edge -- well, more like some very large humanoid footprints, which dwarf his own. Then, while filling-up the bucket, he hears some very unnatural growling and grunting emanating from the surrounding woods. Quickly matching those footprints to whatever's making those strange hoots and shrieks -- and there’s more than one of them, which are getting closer by the second, Briggs doesn't like the forming mental picture, hightails it back to the car, where he confides to a disbelieving Hawks what he's seen and heard, and then urges the old man to get them both the hell out of there.

Now, up the road a piece, that dapper biker gang has made their own pit-stop at a general store, where they clean-out every ounce of booze and every cube of ice they can find before motoring further on up into the mountains. After they've cleared off, Hawks and Briggs limp into the store, where the elder huckster immediately tries to sell the store’s owner, Mr. Bennet (Maynard), and his daffy daughter, Nellie (Keller), some of their worthless junk. (And Maynard used to be a huge cowboy star back in the day, judging by all the prominent movie posters hanging on the store’s walls featuring him. He might even be wearing the same 10-gallon hat.)

But we leave the scene before their haggling truly commences, back to the road, where one of those bikers and his old lady split-off from the group for some -- *ahem* “alone time.” But after a brief period of fondling and necking, Rick (Mitchum) withdraws and begins tinkering with his bike’s motor. Thus, with nothing else better to do while he attends to his “Iron Mistress,” Chris (Jordan) decides to do a little exploring but doesn’t get very far before stumbling upon what appears to be an ancient Indian burial ground!

Yelling for Rick, who isn’t the brightest bulb in the world, to come and see what she’s found, he takes in the scene, ominously points out how big the burial mounds are, saying the occupants must’ve been giants, and then proceeds to dig one up because, sure, Why not? Here, he uncovers a corpse that appears to be half-human and half-ape, judging by the unearthed facial features. But before they can excavate and examine any further, I will assume whatever buried that particular body staunchly objects to this desecration of their kin, and shows its displeasure by stomping onto the scene to put a stop to it with extreme prejudice.

Here, we finally see the whole creature that had been lurking and hidden just off screen or out of frame. A large, hulking, human-like beast, covered in scraggly and scotch-guarded hair from head to toe, which proceeds to beat the hell out of Rick, knocking him unconscious, before abducting Chris, ignoring her screams as it slings her over a shoulder and then disappears back into the woods -- fate and destination unknown…

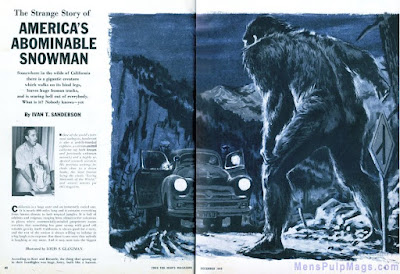

Back around 1959, it was a collection of articles penned by Ivan T. Sanderson in True magazine (among others) that first piqued the interest of amateur filmmaker, Roger Patterson, on the legendary and notoriously reclusive man-ape that (allegedly) roamed the uncharted forests of North America’s Pacific coast.

A devotee of Charles “Fortean” Fort -- the Robert Ripley of even stranger, unexplained phenomenon, Sanderson was kind of the godfather of crypto-zoology -- a term he apparently coined back in the 1940s. And when he wasn’t out on safari all over the world, documenting and publishing tales of his travels, or collecting specimens for zoos and museums, Sanderson was on the radio or TV to showcase both his expertise and his menagerie of Animal Kingdom rarities. He even founded the Ivan T. Sanderson Jungle Zoo in 1952, which covered nearly 25-acres of land near Hainesburg, New Jersey.

Ivan T. Sanderson

But after a two-punch combo of a tragic fire in February, 1955, that cost him dozens of animals, and some massive flooding caused by Hurricane Diane in August, 1955, which essentially destroyed everything else, Sanderson left zookeeping behind and began focusing on writing about another subject that had always fascinated him: cryptids.

Ever since claiming to have been attacked by a giant olitiau on one of his earliest jungle adventures -- which he would later describe as “the granddaddy of all bats,” Sanderson became obsessed with scientifically proving the existence of things like lake monsters, sea serpents, Mokèlé-mbèmbé -- the dinosaur of the Congo, giant penguins (of all things), the Yeti of the Himalayas, and it’s domestic cousin, the Sasquatch, whose first documented sighting dated back to 1811 in what was to become Alberta, Canada, and even further than that when it comes to Native American folklore.

Images courtesy of MensPulpMags.com.

But the idea of an unverified North American primate didn’t get any real traction until around 1955, when William Roe brought back a whopper of a tale. Seems after hiking up Mica Mountain in British Columbia, Roe spotted "a creature between six and seven feet tall that was hairy all over, had large breasts, a Negroid-shaped head, and walked on two legs."

And then things really went nuts a few years later in August, 1958, when a story reported for The Humboldt Times of Eureka, California, broke nationally when workers for the Granite Lumber company found several large humanoid footprints trailing around their worksite as they cut a logging road along the Bluff Creek, which was about 50-miles northeast of Eureka. These mystery prints were 16-inches long and 7-inches wide, which left deep impressions in the soil, indicating something that weighed well over 300lbs, with a stride of about 50-inches -- and even longer where they assumed it picked-up speed. “I don’t know what this thing is,” said Jerry Crew, a worker from the site, who made a plaster cast of one of the impressions. “Nobody does.”

Crew also went on to say that he and his fellow loggers “sometimes have a feeling that they are being watched,” and related another incident from several years prior when something came into a worksite at night and “flung full 50-gallon oil drums around like firewood.” And from this incident forward, as more prints were found and claims of having actually seen what left them spiked around the area, the Sasquatch would forever be linked with a new name: Bigfoot.

Now, it was later revealed this entire incident was a hoax perpetrated by Ray Wallace, whose family, upon his death in 2002, came forward with the wooden molds Wallace and his brother, Wilbur Wallace, had used to make those footprints as part of an elaborate practical joke on a rival logging operation, which then got quickly out of hand, causing the petulant Wallace to continue with his Bigfoot pranking and hoaxing over the decades since. However, if you go back and follow the story as it first played out in 1958, it became readily apparent that even back then everyone knew it was a hoax, and who was behind it.

Apparently, Sheriff Harold Wilson of neighboring Trinity County sniffed it out early, saying in an October 21, 1958, interview for The Record Searchlight (Redding, California) that the whole thing was all due to a “practical joker who has made a huge pair of artificial feet.” Wilson also pointed out that “Bigfoot was a resident of [his] county before he moved north and west into Humbolt county,” where Crew found his bizarre tracks. Seems a similar set of prints showed up around some power lines being built near Redding back in 1947, and, according to Wilson, “It sticks in the back of my mind that some tractor driver who worked on that job has moved into Humbolt county with his big feet.” And while Wilson never actually named the culprit it was fairly obvious who he meant; and as things fell apart, Wallace threatened to sue anyone who accused him of being behind it all until his posthumous confession in 2002, which throws an equally dubious light on the Wallace family claiming he had gotten away with something for over 40-years.

Thus, it was these kinds of unsubstantiated eye-witness testimonies and dubious footprint evidence that Sanderson based his magazine articles on. And all of that culminated with the publication of his book, Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life in 1961, which established a lot of Sasquatch and Bigfoot lore as we know it today.

In the book, according to a review by William Strauss for the April 20, 1962, edition of Science magazine (-- as my attempt to get a copy of the actual book itself wound up “lost” during delivery at the time of this writing --), Sanderson says “there are four types of ‘Abominable Snowmen’ living today, spread out over five continents,” and then broke them down thusly; (one) “subhumans, found in East Eurasia and the Orient, of standard man-size, at least some of which may be Neanderthals; (two) proto-pygmies, inhabiting the Orient, Africa, and possibly Central and Northwest South America, smaller than the average man; (three) neo-giants, occurring in Indo-China, East Eurasia, North America and South America, taller than the average man by at least a foot or two; (four) sub-humanoids, confined to South Central Eurasia, in every way the least human, including the original Abominable Snowmen, the much-discussed and disputed Meh-Teh of the Himalayas.”

Strauss, who was a member of the Anatomy Department of John Hopkins University, was a little baffled by “the author’s concept of what constitutes scientific evidence” and how “the evidence which Sanderson presents is anything but convincing.” And, while “it is possible that some of Sanderson’s ‘Abominable Snowmen’ may actually exist, valid proof of their existence is not to be found in his book.”

Roger Patterson.

Thus and so, it should be noted that this type of fruit from a poisoned tree -- well intended or not-so-well-intended, is what led Roger Patterson and his partner, Bob Gimlin, on their quest to capture photographic evidence and prove, once and for all, that Bigfoot was real.

Patterson was a self-proclaimed cowboy and rodeo rider, who hailed from Yakima, Washington -- while others claimed he was a deadbeat, layabout, good-for-nothing con-artist, who owed everybody money. Either way, it was after reading Sanderson’s account of the recent sightings near Eureka that first drew Patterson to the area around 1964, where he talked to several locals, including Wallace, and allegedly found some fresh Bigfoot tracks. And so, here began his rabid obsession to find “unshakeable evidence” of the creature’s existence -- but not for science. No. He figured it would make him a fortune.

And so, through constant flim-flammery and bilking recent widows out of some settlement money, Patterson’s quest for fortune and glory began in earnest in 1966 with the self-publication of his book, Do Abominable Snowmen Really Exist?, which consisted mostly of newspaper clippings, several eyewitness reports, which were both written and illustrated by Patterson, hand-drawn maps showing where the most recent sightings occurred, and photos of footprints and Sasquatch hunters. And as rumor has it, if you sent in money for a copy, you might’ve gotten one, or you might’ve not.

Then, after convincing about seven people to invest $1000 each, promising each 50% of the profits on his latest endeavor, and I’ll let you all do the math from there, Patterson embarked on his most ambitious Bigfoot project yet: a docudrama, where a group of cowboys are led by an old miner and his Indian guide (played by Gimlin) to a cave deep in the forest, where the creature supposedly lived; and along the way, around the campfire, the party would swap Bigfoot stories -- including the tale of Albert Ostman, who was allegedly kidnapped by a family of Bigfoot in 1924, and the Ape Canyon incident that happened the very same year near Mt. St. Helens, Washington, where a miner’s cabin was assaulted by a group of vengeful, rock-chunkin’ Sasquatch. Of course, to complete this film, logic dictates that Patterson would most likely need some kind of Bigfoot costume for his flashback reenactments and the climax at the cave -- he typed ominously…

Filming commenced on this opus in 1967 over Memorial Day weekend, and lasted three days before the money apparently ran out. Undaunted, Patterson regrouped, abandoned the feature idea, and tried again. And after securing another round of financing through his in-laws, he decided to scale things back a bit for his next proposed feature, Bigfoot: America's Abominable Snowman, which would be a simple documentary chronicling he and Gimlin’s expedition into the Six-Rivers National Forest in Northern California, where they would search the area around Blue Creek Mountain, where people had been finding tracks since the mid-1950s. And it was here, on October 20, 1967, after several weeks of fruitless searching, along the banks of Bluff Creek, where either one of two things happened:

One, according to Patterson and Gimlin, as they came upon a massive logjam in the creek due to some recent flooding, they suddenly spied a large figure partially hidden by this on the opposite bank. Here, Patterson’s horse spooked and nearly threw him. He then dismounted and struggled to extract the camera from his saddlebags, started filming, and then sprinted after his target on foot as it slowly shambled off, causing the picture to distort wildly until he stopped, steadied, and refocused, capturing the creature as it briefly looked back at them before disappearing into the nearby trees. In all, this entire encounter lasted less than a minute; but it resulted with the most hotly contested film footage/evidence since Abraham Zapruder decided to take his camera to the Daley Plaza back in 1963. Or...

Two, it was all a hoax. Now, there had been a long and persistent rumor that what was actually seen in the Patterson-Gimlin film could be traced back to John Chambers, a legendary FX-artist, most noted for his ground-breaking work on Planet of the Apes (1968), which I believe was started by fellow FX-artist Rick Baker, and then perpetuated by director, John Landis. (Or Landis started it, and Baker ran with it, depending on your source.) For his part, Chambers always denied any involvement with Patterson.

However, Philip Morris, owner of the North Carolina based Morris Costumes -- then known as Morris Magic Co., which manufactured costumes and stage props for magic acts and sideshow attractions around the country, including gorilla suits, claims that he sold Patterson a modified gorilla suit back in 1967 over the phone and delivered it via mail-order, which the buyer claimed was going to be used in some kind of prank. But unlike with a lot of Patterson’s business transactions, Morris sniffed out the swindle attempt and actually got paid the $435 upfront before he shipped the suit off to Washington. He also claims to have received several follow-up calls from Patterson and talked him through how to modify the costume even further, including adding a pair of breasts, how to cover-up the zipper properly, and to add bulk by having the wearer use football shoulder pads underneath the suit. He also claimed to have later recognized his suit when the Patterson-Gimlin footage of “Patty” showed up on TV in 1968 but remained silent on the subject for decades, not wanting to break the carnie-code or reveal any tricks of the trade, being a former magician himself, explaining why he didn’t come forward until 2002.

Now, it should be noted that Morris’ claims are one-sided, purely circumstantial, and arguably hearsay as no receipts of this transaction remain. However, his story is corroborated, somewhat, by the admission of Bob Heironimus, who came forward in 1999 with a sworn affidavit, claiming he was offered $1,000 to wear the Morris costume -- or a costume; and so, it was him, not Bigfoot, Patterson was filming back in 1967, claiming you can see his wallet bulging through the costume’s rump and how the sun glints off his glass eye in one of the frames.

For the record, Heironimus claims he was never paid the money promised and might be harboring a bit of a grudge. He also claims he remained silent for so long because he feared he could be charged with fraud or sued by those who owned the film. It should be noted that Gimlin also kinda removed himself from the initial hoopla of the footage once it was revealed -- refusing to accompany Patterson as he took their documentary out on tour, and later, surrendering his share of the rights to it for only one dollar to simply be rid of it -- at least until recently, who still contends to its authenticity.

Strangely enough, there were originally two reels of film concerning the Bluff Creek incident, which showed Patterson and Gimlin returning to where they first saw Patty after failing to track her any further, which shows them filming the trail or prints she left behind and taking plaster casts, one of each foot. But this second reel apparently disappeared early. Why? Did it show something that gave the game away? Or did it just get lost over the initial dispute over who owned the film. And who knows? Maybe it was all real? Maybe Patterson really did buy a suit from Morris for that aborted feature and, like the feature, it didn’t pass muster and was abandoned. Or maybe they shot something for that feature with the costume, realized how good it looked, and decided to pass if off as real and just run with it? Who can say for sure.

Thus, to some the footage was the smoking gun that proved Bigfoot’s existence, while others felt a confederacy of dunces managed to pull-off the greatest con of any century. And as of this writing, over 50-years later, the debate still rages. In the end, real or faked, Patterson got his infamy, but the financial reward never really surfaced. Quite the opposite, actually.

It began with a warrant for his arrest, sworn out by Harold Mattson, owner of Sheppard’s Camera Shop of Yakima, Washington, for failing to return the camera he had rented to capture the disputed footage in a timely manner. Patterson was arrested on this warrant in November of ‘67, but the charges were subsequently dropped when the camera was finally returned in working order. He then spent the rest of his life barely staying one step ahead of several lawsuits, creditors, and collection agencies as he continued to search for more evidence of Bigfoot’s existence and that elusive big payday. Alas, Patterson would succumb to cancer in 1972. And from his deathbed, just a few days before he died, Patterson took one last shot at all the naysayers, telling author Peter Byrne how “he wished he would’ve just shot the thing and brought out a body instead of a reel of film.”

Now, whether you believed them or not, it was the Patterson-Gimlin footage that really kicked off the whole Bigfoot phenomenon that lasted for nearly a decade (1967-1977), as sightings of the giant hairy creatures started happening all over the country. And like it’s cousin, the Yeti, who made his big screen debut back in 1954 with W. Lee Wilder’s The Snow Creature (1954), which was then followed by Jerry Warren’s Man Beast (1956) and Hammer Studio’s The Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas (1957), it was time to get Bigfoot his very own movie, too. Enter Anthony “Tony” Cardoza.

Anthony Cardoza.

After being honorably discharged from the army after serving with distinction in Korea as part of an artillery unit, Tony Cardoza returned to his hometown of Hartford, Connecticut, and got a job at Pratt & Whitney Aircraft, working as a skilled welder on jet engines. Around 1957, Cardoza got an irresistible itch to get into show business, wrangled himself a transfer to another manufacturing plant in California, sold his house, and moved out west, where he continued to work as a welder and ran into an old friend from back home, who knew a guy, a film producer, who was looking for financial backers on his next picture and swore anyone who pitched in would double their money -- guaranteed.

Now, the producer in question was Ed Wood, and the film was Revenge of the Dead -- sort of an unofficial sequel to Wood’s Bride of the Monster (1955), where Wood smushed together several abandoned projects, including an attempt at a TV-pilot, Final Curtain, for a stillborn TV-series, Portraits in Terror. Perhaps unaware of Wood’s “unique” reputation for over-selling shares and deficit-spending budgets (-- Wood and Patterson were kindred spirits, apparently), Cardoza was all in, using the money he’d made selling his house.

Alas, those of you who know you’re B-movie lore are well aware that while Revenge of the Dead was completed, it was never officially released, then kinda disappeared, and was considered a lost film for decades until Wade Williams found it in 1984, sitting on a shelf at Film Service Laboratory Inc., where it had sat since 1958, held as collateral, because the production had run out of money and couldn’t pay for the lab’s processing fees. Williams then got these reels out of hoc and finally released the feature on home video under its alternate title, Night of the Ghouls (1959).

Needless to say, Cardoza took a bath on the film, but as an associate producer he did get some hands-on experience in making a movie -- and even managed to snag himself a starring role. He then continued to dabble in the business on the weekends and to weld during the weekdays until he got a phone call from out of the blue from Coleman Francis, who wanted to know if Cardoza knew how to get a hold of Wood-regular, Tor Johnson, the wrestler, who had co-starred in Bride of the Monster, Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) and, eventually, Night of the Ghouls.

Francis was a bit player and background filler -- if you look quick you might’ve seen him as ‘Guy in Power Plant Answering Phone’ in Killers from Space (1954) or as a delivery man in This Island Earth (1955). But now, he had written a script and wanted Johnson to star in it as a defecting Russian scientist, who gets irradiated by an atomic blast while wandering the desert, as you do, while trying to escape from several KGB assassins. Mutations, murder and mayhem ensue as we ponder a flag on the moon, and how it got there.

Intrigued, and ready to try again, Cardoza not only got Johnson to be in the film, he signed on as a co-producer and took another role in front of the camera -- several of them, actually, along with Francis, who also directed, as the film wound up taking nearly a year to complete. The end result of which, The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961), is 54-minutes of something barely coherent and an absurdists’ delight of circular narration, mistaken identity, and watching a poor 300lbs man get sun-stroke as he is consistently and persistently herded around the desert until he keels over dead. The end.

Cardoza and Francis were soon at it again with the even cheaper The Skydivers (1963), a tale of jealousy, revenge, and falling out of the sky, and Red Zone Cuba (1966), an unfathomably bad attempt at a Donald Westlake-type adventure, where a trio of convicts (Francis, Cardoza and Harold Saunders) wind up part of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, get captured during this historical debacle, escape, and then try to fleece the widow of one of their former cellmates because of course they did.

Next, Cardoza left Francis behind for his next feature,The Hellcats (1968), cashing in on the current Outlaw Biker surge at the box-office, thanks to Roger Corman’s The Wild Angels (1966), with the tale of a female biker gang -- "Motorcycle Mamas on a Highway to Hell," wrapped-around a murder plot. Designed to help establish Cardoza’s newly minted Gemini-American Productions, the film was based on an original story by James Gordon White, a genre vet, who had already penned The Glory Stompers (1967) and would go on to write The Mini-Skirt Mob (1968) and Hell’s Belles (1969), and would be directed by Robert Slatzer.

We’ll have more on Slatzer in just a bit. Cardoza, meanwhile, had a lot riding on this feature. Under doctor's orders to give up on welding as a profession or go blind, it was all or nothing. And while The Hellcats was Cardoza’s first bona fide hit, with the Outlaw Biker flick already starting to slip its clutch and sputter due to over-saturation, the producer felt it was time to do something else to stay profitable. Something equally exploitable, that had never been done before -- but, just to be on the safe side, salt the idea with some biker elements and bikini babes and a few recognizable names for the marquee.

Thus, it was Harrison Carroll who officially broke the news in his syndicated column, Behind the Scenes in Hollywood (March 12, 1969), saying, “First to reach the screen with a picture about those half-ape, half-human monsters who are supposed to roam the mountains of northern California will be producer Tony Cardoza. This is not strictly dream-up stuff. There is much evidence, including actual film shots (-- a reference to the Patterson-Gimlin film), that these monsters do exist. They look to be eight or nine feet tall, have hairy bodies like apes but a number of human characteristics such as buttocks like men. (Editor’s note: Buttocks?!) The theory is that they are the missing link between apes and Neanderthal man. He calls the picture, Bigfoot (1970).”

And together, Cardoza, Slatzer and White concocted something somewhere between a coconut-to-the-cranium-induced Gilligan’s Island fever dream sequence and Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom because you will not believe where all of this is headed, or maybe you can, but stick with us anyway as Rick slowly recovers from his pummeling after desecrating the Bigfoot grave. And with Chris nowhere in sight, and his biker pals long gone, he heads back to Bennet’s store and calls the authorities.

Alas, Sheriff Cyrus (Craig) doesn’t believe the young man’s wild story about a monster and a missing girl; and feeling it's just a prank of some sort, impatiently hangs up on him. With that, Rick goes with plan-B, calls up his biker buddies next, and says to get their buttocks back up the mountain because something kidnapped Chris -- well, make that, some >thing<.

Overhearing all of this, and smelling money to be made, Hawks is definitely intrigued by the profitability of capturing one of these creatures and offers to help. Taking anything he can get, Rick, along with the two bickering con-men, retrace his steps back to the Bigfoot graveyard. And here, having to abandon the car, we get the first of many interminably looooooong walking sequences: they walk, they climb a little, and then walk some more. And as they walk, and walk, and walk, Hawks assures the boy not to worry because he’s an expert tracker; but truthfully, they're the ones who are really being hunted as the sun goes down!

So, What happened to Joy and Chris? Glad you asked, because they’re currently tied to a couple of stakes further up the mountain, under the day-for-night moonlight, at Bigfoot central. And while Chris keeps asking Joy all kinds of plot-specific questions, Joy keeps coming up with these really plot-specific answers in perhaps one of the funniest exposition dumps I've ever seen: for, according to the ever-postulating Joy, the girls have been captured as breeding stock to help replenish the dwindling Bigfoot population -- and there's already a little half-human, half-Bigfoot hybrid critter in the camp that seems to prove her running thesis correct!

And so, with this plausible conclusion reached, while Chris is terrified by the prospect of being ravaged by one of these hairy beasts, Joy has the uneasy feeling she’s being saved for something else. Apparently, there is something even worse living higher up in the mountains, and [ORGAN STING/] she is to be sacrificed to it! [/ORGAN STING]

Come the dawn, in somewhat of a surprise, Sheriff Cyrus actually follows-up on that phone call and visits Bennet's store, where Nellie fills him in on what’s happened since. Now, the Sheriff still doesn’t put much stock in this Bigfoot sighting but passes it along to the nearest Ranger Station. Guaranteeing him there is no such thing as Bigfoot, the head Ranger (Weaver) promises to keep their eyes peeled for this new batch of missing persons.

New missing persons, you ask? Yeah, see, on top of this latest report, and the missing pilot, apparently another couple disappeared awhile back, too -- and I guess that explains where the little half-breed Bigfoot came from. Also of note, in that last scene, while Ranger Danger was on the phone, there’s a large picture window directly behind him. And, of course, just as he obliviously denies their existence, one pops into view. It’s totally telegraphed, you totally know it’s coming, but I’ll be damned if it still didn’t crack me up. Sight-gag! High hilarity! Gawd, I love this movie. Anyhoo…

Proving to be expert trackers, too, Rick’s biker buddies -- led by Wheels and his old lady, Peggy (Crosby, Wilkerson), find the Bigfoot burial ground. Here, a couple of them chicken-out when they spy the unearthed corpse but the others press on.

Meanwhile, Rick, Hawks and Briggs are still walking. (For what? Like, twelve hours now?!) Walking. Walking. Walking. Then they walk some more. Then, not so suddenly, they’re ambushed by a whole horde of walking carpet samples and are quickly staked-out beside Joy and Chris.

Down the mountain apiece, and slightly off their trail, the other bikers stumble upon a cabin owned and occupied by a couple of Indians, Hardrock (Chissell), and his pal, Slim (Raymond). Next, we get some more history as Hardrock relates the story of the Sasquatch -- what you people call Bigfoot, he says, and how he lost an arm when confronting the beast many moons ago. And while the other bikers intently listen, Dum-Dum (Cantrell), the most slovenly member of this clean-cut bunch, finds some dynamite in a nearby storage shed. And with that, now armed, and with their new Indian guides -- seems Hardrock wants a little payback for having his arm wrenched off, this makeshift posse continues the search for their missing friends.

Meantime, back at the Bigfoot nest, it's finally sacrifice time! Thus and so, dragged away from the others and still further up the mountain, Joy is staked out between two trees in a scene that is looking very familiar but I can’t quite place it. And then something huge and horrible, roaring madly, starts crashing through the trees toward her -- now where have I seen this before, dammit? And then the girl screams as the biggest Bigfoot of all breaks out of the woods and starts thumping his chest.

But before the beast can claim his new bride, suddenly, a bear also comes into this clearing, sees Joy, and decides to eat her. But! Never fear, as the bigger Bigfoot intercedes on her behalf as these two beasts lock in deadly, mortal combat … Well, actually, it's kinda sad, and pathetic, as the guy in the Bigfoot costume tag teams between wrestling a bear rug -- not a guy in a bear suit, mind you, just a rug, and an old, arthritic and toothless Sun Bear, who would rather be anywhere else but here; and they just kinda roll around and flop about like a couple of landed fish.

Meanwhile, during this *ahem* “melee” Joy manages to free herself and runs away just as the bigger Bigfoot kills the bear rug -- which magically grows some pretty impressive teeth after it dies, and then thunders after her.

Meanwhile, meanwhile, when the other bikers finally find the rest of the gang and free them, Hardrock starts blasting away with his pistol and kills one of the smaller creatures. As the other beasts scatter, Hawks manages to catch the little hybrid, secures it, and then he and Briggs try to sneak it away during the confusion. But another Bigfoot comes to the rescue, stealing the little critter back. Undaunted, Hawks quickly offers a cash reward to anyone who will help capture one of these creatures alive. Here, Rick, Chris and Briggs have had enough and head back down the mountain, but the rest take him up on the offer; and so, the hunt continues.

Zeroing in on Joy's screams when the big Bigfoot finally recaptures her, Hawks’ hunting party tracks them to a cave, where Hardrock shoots the beast in the leg, allowing Joy to get away. Wounded badly, the creature retreats into the cave and Dum-Dum, despite the fact that he didn't light it first, throws the bundle of dynamite in after him. And upon its spontaneous detonation, the resulting, massive explosion can be heard and felt by all of the locals that we’ve met so far, who give pause and look up in astonishment.

When the smoke clears it's all over; the monster is either dead or sealed up inside the cave. And as the group slowly retreats back down the mountain, when Dum-Dum slobbers the dynamite got him, Hawks thinks otherwise. And as he consoles Joy, offers that, "No. It was beauty killed the beast."

Boo, movie! Boo! Mr. Cardoza, I have seen King Kong (1933). I have watched King Kong (1976). And I have been being watching King Kong (2005). And sir, your Bigfoot movie is no King Kong. However, having said that, omigod, I still love this stupid movie.

Hookay, now, Where were we? Ah, yes, finally circling back to Robert Slatzer, the director of our fine fractured feature film, and no stranger to conspiracies or hoaxes himself. A native of Ohio, Slatzer was a newspaper reporter who left his job at the Columbus Dispatch and moved to Hollywood around 1946 to ostensibly write about the movies. Throughout the 1950s, he bounced around between several studios -- RKO, Monogram, MGM and Paramount, working in some capacity, most likely as a publicist; and while his obituary (March, 2005) is a bit vague, it claimed he had a hand in producing episodes of Highway Patrol (1955-1959) and Wagon Train (1957-1965) but not how. This same obit also claimed he became an executive producer at Republic Studios in 1953, and then formed Jaguar Pictures in 1959, but I can find no credits for him under either of these banners -- or any credits at all, really, before The Hellcats in 1968.

Robert F. Slatzer.

Slatzer would pitch-in on the scripts for both The Hellcats and Bigfoot -- originally released as Big Foot, two words, at least according to the poster, which contradicts the main title credit. After that, again, according to that dubious obit, he allegedly made the films Cowboy and the Heiress (1970), The Young Wildcats (1971), Campaign Girl (1972), and The Punishment Pawn (1973) but all searches for these titles also turned up nothing, meaning they were scripts that never got filmed or, judging by the titles, maybe they were adult material? That’s me shrugging right now. In fact, the only other verified credit I could find for Slatzer aside from The Hellcats and Bigfoot was for being an executive producer on the western comedy, Mule Feathers (1978).

And while his film career was a little sketchy to the say the least, Slatzer did get several books published, including a scathing look at the notorious family life of actor and crooner Bing Crosby with The Hollow Man (1981), and he co-authored a retrospective with Donald Shepherd and Dave Grayson, The Duke: the Life and Times of John Wayne (1985). But it was two books on Marilyn Monroe that really got Slatzer noticed -- and for all the wrong reasons.

See, in his book, The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe (1974), Slatzer claimed that he and Monroe were actually married in Tijuana, Mexico, back in October of 1952. But it wasn’t meant to last as, according to Slatzer, an enraged Daryl F. Zanuck forced Monroe to annul their marriage just three days later. This fairy tale was later adapted into a Made for TV-Movie, Marilyn and Me (1991), but Slatzer’s alt-history claims were full of holes and didn’t hold up very well under careful scrutiny. But he insisted it was all true; and between the first book and his follow up, The Marilyn Files (1992), Slatzer also constantly banged the drum that Monroe didn’t die of an accidental overdose but was covertly assassinated to cover-up her affairs with both John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy.

All well and good, but what kind of skills did Slatzer have as a film director? Well, I can’t really comment on The Hellcats because I’ve only seen that once and it was a cropped ‘n’ chopped version shown on Mystery Science Theater 3000 (Season 2, Episode 9); and while I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve sat through Bigfoot (-- still have the giant VHS clamshell I bought from the Video Kingdom back in the day), all I can say about the director’s style is it’s perfunctory -- no more, no less, as half of this film is nothing but long shots of people walking from one side of the screen to the other, while the other half is an assortment of establishing shots, master shots, slow zooms and pans -- and cinematographer Wilson Hong seems weirdly obsessed with rack-focusing on trees.

Slatzer wasn’t helped at all by the meanwhile, meanwhile, meanwhile of the meandering plot as it keeps jumping around between the myriad parties making their way up the mountain, looking for each other, which also leads to some cognitive whiplash as editors Hugo Grimaldi and Bud Hoffman cut back and forth without any brakes. And it’s quite maddening how quickly the film jumps from location footage to sound-stage shots, and how the day-for-night filters never quite hold up in continuity.

Now, the film’s closing credits claim it was filmed on “actual locations” where the Bigfoot have been sighted, but it was actually shot in the Tehachapi Mountains, which are just north of Los Angeles and about halfway to Bakersfield, which is hell and gone from Bluff Creek. The indoor scenes were split between Empire Studios and Colorvision Studios and the canned nature sets are really quite good if I’m being honest.

Mention of a positive nature should also be made for Richard Podolor’s soundtrack. Podolor became a studio musician at the age of 16 back in the 1950s, who first broke out writing “Teen Beat” and “Let There Be Drums” for Sandy Nelson and would later play on recordings for the Monkees, the Turtles, and the Grateful Dead. He started producing albums in the 1960s for acts like Steppenwolf, engineering their hit “Born to Be Wild” and several records for Three Dog Night, including “Mama Told Me Not to Come” and “Joy to the World.”

He first got on Cardoza’s radar for The Hellcats, for which he provided a couple of tracks -- "Mass Confusion" and "I Can't Take a Chance." Polodor then followed that up by composing the entire soundtrack for Bigfoot. I really dig the lo-fi fuzz and reverb of the main title track that comes off as kinda creepy and almost mournful. And while it does get a little slap-happy in spots, especially with those blaring organ stings, and heaps on the cornpone and galloping guitars a little too thick, overall, I think it only adds another layer of loopiness to the proceedings. And according to the print ads, there was an original soundtrack album for Bigfoot released through Panardma Records that included music from the film and “original Bigfoot sounds” just waiting for a needle-drop. Hello, new Holy Grail.

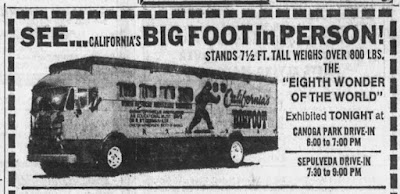

Also, I want to point out another awesome piece of ballyhoo from when the film was finally released in 1971 through Ellman Film Enterprises. Apparently, when Bigfoot played at select Drive-Ins, hopefully at one near you, there was a traveling exhibition that accompanied it, where you could “See! California’s Bigfoot in Person!”

Now, this alleged carcass stood 7-feet tall, weighed over 800lbs, and was chauffeured around in what looks like a converted bus or moving van. I have no idea if this touring contraption made it anywhere outside of the Los Angeles area, but I did find a few Drive-In ads around the country that advertised you could see Bigfoot on exhibit before the show. Regardless, I want to find this vehicle, restore it to its original glory, and then live in it for the rest of my natural life.

Unfortunately, what people actually saw inside the vehicle remains unknown, as my web-fu failed to turn up much info on the promotion other than the ads. Perhaps it was a stuffed costume leftover from the film on display? Or maybe someone wore the costume and appeared at some strategic blackout point during the screening? I simply do not know.

And I know I made fun of them throughout the plot write-up, but having seen a metric ton of shitty Bigfoot movies throughout my misbegotten life I can honestly say the assortment of costumes presented here weren’t THAT terrible. Honest. I’ve seen much worse -- looking at you, Curse of Bigfoot (1976) and Suburban Sasquatch (2005). Credited to Merci Montello -- a/k/a Mercy Mee, an actress, who appeared in Space Thing (1968) and The Bushwhacker (1968), the off-the-rack origins are obvious but they play pretty well on-screen. (I think the assortment of fright wigs helped sell 'em.)

And I can’t remember where or when I saw it, but I recall FX-artist Stan Winston -- The Terminator (1984), Aliens (1986) and Jurassic Park (1993), commenting on the Patterson-Gimlin footage once, who scoffed at it, saying it was obviously a man in a suit, and whoever built it would never get hired or a hold a job in Hollywood with that kind of craftsmanship. Now, having heard that, I want you to compare the efforts of Bigfoot to whatever that is in the Patterson footage. Yeah. Go on. I can wait.

According to Keller’s article, Robert “Big Buck” Maffei, who stood over seven feet tall and tipped the scales at 450lbs, and who most famously played the giant cyclops in the Lost in Space (1965-1968) pilot episode and the anthropoid of Taurus II in the "The Galileo Seven" episode of Star Trek (1966-1969), was supposed to play the alpha Bigfoot but this obviously fell through as his name does not appear in the credits. Playing the little hybrid was Jerry Maren, who was one of the OG munchkins in The Wizard of Oz (1939) -- I think he was a member of the Lollipop Guild. And rounding out our Bigfoot actors we have Gloria Hill, Nancy Hunter and Aleshia Lea as the “Female Creatures,” Nick Raymond, pulling double-duty as the “Evil Creature,” and James Stellar subbing in for Maffei as the alpha “Bigfoot -- the Eighth Wonder of the World.” Holy crap, but Cardoza really overplayed the King Kong angle on this one.

As for the main cast, Bigfoot would mark John Carradine’s 385th film, who is great, as always, and showed no signs of ever slowing down. And this would be Ken Maynard’s first acting assignment since 1944 and The Harmony Trail (1944) and his last. The cast was also littered with Mitchums, starting with John Mitchum and ending with his nephew, Christopher Mitchum, who, of course, was the son of Robert Mitchum. I’ll always remember John Mitchum as Hoffenmueller, Fort Courage’s German Indian translator, who knew six native languages but couldn’t speak any English, on F-Troop (1965-1967), but you might remember him as “Fatso” DiGeorgio, Harry Callahan’s partner in Dirty Harry (1971), Magnum Force (1973) and The Enforcer (1976).

And Christopher Mitchum has had quite the career in exploitation movies, both foreign and domestic, from Italy to the Philippines, in things ranging from Master Samurai (1974), The One Man Jury (1978) and Angel of Death (1985). The younger Mitchum was a last second sub, replacing Jody McCrea when his salary demands weren't met. He wanted $10,000, Cardoza offered $500. Mitchum took the $500 on condition that he could direct some of the second unit scenes.

Joi Lansing was a bombshell model turned bombshell actress, and will probably be a familiar face and figure from roles in Touch of Evil (1958), The Atomic Submarine (1959) and Hillbillys in a Haunted House (1967). Bigfoot would also be her last film role, as she would tragically pass away from breast cancer less than a year later. Rounding out the cast, we have Judy Jordan, Lindsay Crosby, whom I’m sure told Slatzer all about his old man between takes, and Joy Wilkerson, who was Cardoza’s wife at the time. Sharp eyes will also spot Haji -- of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) fame, Memphis Mafioso Sonny West, Ray Cantrell, who would go on to write The Zodiac Killer (1971), and Doodles Weaver as the odious comedy relief.

This film baffles my brain. By all rights, it is terrible. Awful, even. And yet … I don’t know, maybe it was the joy of watching Joy and Chris spitballing on the mating habits of Bigfoot? Or perhaps the sheer insanity of a Bigfoot vs. Biker flick to begin with -- and I often wonder if Cardoza and Co. returned all those matching Yamaha bikes back to the dealer they borrowed them from in a timely fashion, or if this publicity drummed up any business at all for said dealership? Or perhaps once again, nostalgia has rotted a hole in my judgment centers of what passes for Mission Control in my gray matter.

You see, I grew up during that initial Bigfoot-Mania era, and was completely saturated by it. From Bro’ Smith’s novelty Bigfoot song giving me the drizzles whenever it came on the radio, to the countless documentaries -- Bigfoot: Man or Beast (1972), The Mysterious Monsters (1975), feature films -- The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972), Creature from Black Lake (1976), to Saturday morning entertainment -- Bigfoot and Wildboy (1977), to a board game from Milton Bradley, to him showing up in a couple of favorite episodes of The Six-Million Dollar Man (1974-1978) and The Bionic Woman (1976-1978), and still carrying a grudge that Santa never brought me a Bigfoot action figure from the same, to being disappointed in George Lucas because Chewbacca wasn't a Space Bigfoot but a Wookie, to the hundreds of magazines and books on the subject matter sniffed out at the library, which were read and reread constantly, and to a point where a couple of teachers were starting to worry about this obsession.

And back then, man, I believed. Now, some forty years later, and having survived another surge in ‘Squatch reality programming, which was more about the Bigfoot hunters than the cryptid itself, as more and more classical “evidence” came into doubt, and more hoaxes are revealed, I’m not so sure anymore. I guess I like the idea of Bigfoot, and something being out there that we can’t quite explain. So I believe in the possibility of Bigfoot, and I do not regret one second of time spent on the subject matter over the years, including all the times I’ve sat through this movie or digging into its production history -- hopefully, you won’t either. And now, if you’ll excuse me, I have to waste just a little bit more time dedicated to Bigfoot, trying to track down a copy of that soundtrack album, which is proving more elusive than the creature itself. TO THE EBAY!!!

Originally posted on May 5, 2000, at 3B Theater.

Bigfoot (1970) Gemini-American Productions :: Ellman Film Enterprises / EP: Herman Tomlin / P: Anthony Cardoza / AP: Bill Reardon / D: Robert F. Slatzer / W: Robert F. Slatzer, James Gordon White / C: Wilson S. Hong / E: Hugo Grimaldi, Bud Hoffman / M: Richard A. Podolor / S: John Carradine, Joi Lansing, John Mitchum, Christopher Mitchum, Judy Jordan, Ken Maynard, James Craig, Joy Wilkerson, Lindsay Crosby, Dorothy Keller, Doodles Weaver, Ray Cantrell, Noble 'Kid' Chissell, Nick Raymond

No comments:

Post a Comment