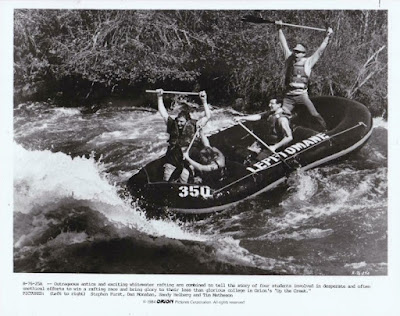

“There can’t be a winner, if there isn’t a river.”

Opening on a fairly active Sunday morning at what's left of LePetomane University after a wild Saturday night, four miscreants are forcefully rounded up by campus security for an audience with the Dean. LePetomane, of course, is from the French, le petomane, meaning “the professional flatulator,” Fart U, which should be your first big clue as to the depths-of-dumb this film is willing to auger itself into --- and we’ve barely just started.

Now, apparently, since the only thing any student at good ol’ “Lobotomy U'' has ever won was an early parole, Dean Birch (Hillerman) wants a Victory with a capital V for his beloved Alma Mater in the upcoming Intercollegiate Whitewater Raft Race.

And to those ends, Bob McGraw (Matheson), a career student with more than twelve years of higher learning under his belt with just as many major and University changes to boot, lovelorn Max (Monahan), who can never get a date, Gonzer (Furst), a gluttonous halfwit, and Irwin (Helberg), a nerdy dork with a penchant for hard liquor, have been chosen for this honor because they have nothing left to lose. For they aren't at the bottom of the list, purports the Dean, but they ARE the bottom of the list. And to sweeten the pot, Birch offers them all degrees, in any subject, if they can somehow manage a win.

Thus, with the set-up neatly tucked away in one helluva hurry, our boozed-up quartet of perennial losers, accompanied by Bob's wonder dog, Chuck, head to the river. At a pit-stop along the way, however, our plot thickens a bit when Bob meets Heather (Runyon), who just bounced her former boyfriend, Rex (East), head preppie of Ivy University.

Meanwhile, Rex and his cronies -- who all appear to be clones of Vincent Van Patten, are in cahoots with Tozer (Sikking), a crooked Ivy alum, who just so happens to be the organizing sponsor of the race. Armed with torpedoes and oars that double as harpoons, any vessel they can't disable, Tozer vows to disqualify, meaning victory is all but assured for the Mighty Crimson of Ivy U.

Still, the early favorites to win are the cadets of Washington Military Institute, led by the *ahem* “inspired” Captain Braverman (Novak). That is, they were the favorites until Bob accidentally interrupted Braverman’s own sabotage attempts, which gets him blown up and WMI disqualified.

Thus, with the start of the race fast approaching, while Bob is a moving target from many scopes, Max strikes out (-- a lot), Gonzer eats (-- a lot) and Irwin drinks (-- a lot). Alas, after Bob and Heather slip into something more comfortable (-- namely, each other), Rex and the Van Pattens come calling, catching them post-flagrante delicto, and prepare to pound our hero into mush…

Man, poor Otter. Does this, like, happen to him in every movie? Anyhoo, according to his obituary in the Los Angeles Times (September 18, 2001), legendary schlock producer Samuel Z. Arkoff’s personal motto was, “Thou shall not put too much money into one picture. And with the money you do spend, put it on the screen. Don’t waste it on the egos of actors or nonsense that might appeal to highbrow critics.”

And as we've touched on in a few film reviews already, this mantra had served American International Pictures pretty well since its inception back in the early 1950s -- co-founded by Arkoff and his long-time partner, James Nicholson, allowing the ‘little movie studio that could’ to evolve from a major minor into a minor major in the Hollywood food-chain.

Now, another one of the key ingredients to the studio’s success and longevity was that it learned early to tap into the burgeoning and under-exploited youth market. “It was an area the major companies had ignored,” said Arkoff. “Their idea of a youth movie was an Andy Hardy film with Mickey Rooney getting into a fix and going to his dad.” Instead, AIP gave us the likes of Dragstrip Girl (1957), Runaway Daughters (1957), Rock All Night (1957), High School Hellcats (1958) and, of course, the two-punch combo of I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), which made them millions and officially put the studio on the map.

After that opening salvo, the studio kept chasing fads throughout the 1960s and early ‘70s -- from beach bunnies, to beatniks, to outlaw bikers, to the counterculture revolution. And, well, turns out the brass at AIP had their own secret weapon when it came to what was hip and happening -- their own kids. As frequent collaborator Roger Corman put it in Arkoff’s obit, “I think Jim [Nicholson] and Sam [Arkoff] understood the younger market. They had children who were young at the time, and I think that kept them in touch with it.”

Susan and Jim Nicholson, Louis Arkoff, Sam and Hilda Arkoff, Donna Arkoff (1966).

Arkoff’s son, Louis “Lou” Arkoff -- named after his grandfather, was born in April of 1950, and his daughter, Donna Ruth, arrived a year later in October, 1951. And Arkoff often spun apocryphal tales in several interviews and in his autobiography, Flying Through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants, on how he would often screen his films for his kids and their friends and take the temperature of the room to see if they were getting things right.

Louis Arkoff would eventually follow in his father’s footsteps by first becoming a lawyer. And while attending law school, he moonlighted at AIP in the early 1970s doing scut work for the old man. Seems that after a falling out with Tom Loughlin during the production of Billy Jack (1971), AIP made a rare blunder when they cut ties with the production. Now, Billy Jack, of course, was a sequel to The Born Losers (1967), a rape-revenge outlaw biker flick, where the character of Billy Jack was introduced -- an ex-Green Beret half-breed Navajo pacifist, played by Loughlin, with a penchant for helping hippies and putting his right foot into the left ears of racist rednecks, and they’d never see it coming, which AIP had financed and distributed. And when The Born Losers became a modest hit, both parties had agreed that a sequel was in order -- but they didn’t agree on a whole lot after that.

See, after viewing the early nonsensical rushes for said sequel, Arkoff and Nicholson made the decision to cut their losses and bail on the film, feeling it would bomb if it ever got finished. But! History would show Laughlin persevered through several more studios before he finally did finish with Billy Jack, which struck a chord with audiences, became a bit of a cultural phenomenon, and made millions -- for Warner Bros. I was there, it’s all true. “One tin soldier rides ah-way…Bah! Badapbop Bah! KEY CHANGE! Bah! Bah! Badapbop Bah! Go ahead and hate your neighbor, go ahead and cheat a friend…” *ahem* Yes. This is all relevant. I swear. Well, not really. Maybe. Sort of. Anyhoo…

Thus and so, yet another sequel was warranted to keep cashing in. Here, Laughlin and AIP buried the hatchet long enough to get the ball rolling on The Trial of Billy Jack (1974). This time, Laughlin backed out on the deal, putting him in breach of contract. Meantime, to cash in on the current Billy Jack craze, Arkoff and Nicholson had decided to re-release The Born Losers back into theaters with a new promotional campaign that emphasized, “The Original Billy Jack is Back!”

Laughlin, in turn, counter-sued the studio over this, claiming they were infringing on his intellectual property. When the case went to court, the judge sided with AIP but mandated they had to clearly state that The Born Losers was not a new Billy Jack film but a reissue, and all advertising and promotional materials had to state this not once, but twice. And so, one of Lou Arkoff’s first jobs in show-business was to collect tearsheets from newspapers all over the country wherever The Born Losers was playing to make sure the studio was complying with the judge’s court order until the case was eventually settled.

Young Arkoff would soon earn a promotion upon graduation, when he was appointed as legal administrator for AIP in 1973, which wasn’t long after Nicholson had left to start his own production company. Louis would also get a crash course on the pre-production plumbing of filmmaking.

According to his father’s autobiography, Louis is credited with casting Nick Nolte and Don Johnson for Return to Macon County (1975) as the studio struggled while the 1970s progressed. With escalating production costs, and the fact that the major studios were now making AIP style B-movies but with A-Budgets with the likes of JAWS (1975), Star Wars (1977) and Smokey and the Bandit (1977), American International floundered a bit as it tried to compete with the emergence of these all-out blockbusters that tended to stick around, which then tended to freeze their product out of theaters as drive-ins went the way of the dodo.

Thus, the writing was kind of on the wall when Louis was promoted to vice-president of American International in 1976. That same year, he would produce his first feature: A Small Town in Texas (1976), a fairly effective entry in the high-octane, redneck revenge subgenre written by William Norton -- White Lightning (1973), Big Bad Mama (1975), and directed by Jack Starrett -- The Losers (1970), Race with the Devil (1975). He would follow that up with Joseph Ruben’s Our Winning Season (1978), a coming of age melodrama, and John Hancock’s California Dreaming (1979), an offbeat tale where a young urbanite tries to wheedle his way into southern California’s surf scene. And then there was Sunnyside (1979), where they tried to cash in on John Travolta’s sudden rocket to fame after Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Grease (1978) by making a leading man out of his brother, Joey Travolta, hoping lightning would strike twice. It didn’t.

1978 would also be the first year where AIP actually spent more money than they brought in -- and by a substantial margin. It also marked the beginning of the end for Arkoff and the studio he co-founded as he was forced to merge with Filmways Inc. to stop this hemorrhaging of cash. And while things seemed to turn around a bit in 1979 with the highly successful releases of Love at First Bite (1979) and The Amityville Horror (1979), the profits they generated were quickly eaten up by the bungling attempt to import a hideously redubbed Mad Max (1979) and, of course, the release of Meteor (1979), a disaster movie in more ways than one; an all-star box-office boondoggle that was the complete antithesis of what had allowed AIP to stay successful, competitive, and in production for over 25-years as Arkoff’s new partners wanted to piss with the big boys but only wound-up whizzing down their own legs.

Arkoff saw this coming, but his protests fell on deaf ears. Thus, after producing or presenting over 500 films, Arkoff officially left the studio in 1980. Not long after, Filmways would merge with Orion Pictures and American International Pictures would, essentially, cease to exist -- a rather ignominious end to the storied franchise.

But AIP would live on, sort of -- well, at least in spirit as Arkoff started over by founding his second independent production company, Arkoff International Pictures (AIP). And one of the first films he backed was Larry Cohen’s Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), where an ancient Aztec deity terrorizes New York City, which led to Arkoff’s infamous encounter with critic Rex Reed, who praised Michael Moriarity’s method performance in Q that stood out so sharply amongst all the dreck, to which Arkoff replied, “The dreck was my idea.”

And always one to follow trends, and there was nothing hotter at the box-office in the early 1980s than a slasher movie, Arkoff also backed Joe Roth’s The Final Terror (1983) -- though it probably didn’t hurt that Roth was his son-in-law, who had married Donna Arkoff in 1980.

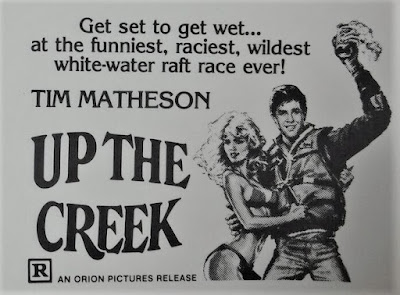

Meantime, the last thing Louis Arkoff produced for American International was a rather dubious Meatballs (1979) cash-in called Gorp (1980), which would also prove to be the original AIP’s last feature -- yet another ignominy the once fabled studio must endure. He would then kinda follow what was left of the company to Orion, where he picked up on a script by Jim Kouf called Up the Creek (1984), a comedy whose origins can be traced back to Animal House (1978), I think, as it pivots on the usual collegiate slobs vs. snobs shenanigans. And one could possibly argue that it was kind of a soft reboot of AIP's Beach Party (1963) -- only this time, Frankie and Annette actually do it, and more than once.

Yeah, if there was one thing that was just as popular as teenage bloodbaths at the movies during this period -- Friday the 13th (1980), The Burning (1981), My Bloody Valentine (1981), it was the concurrent rash of teenage boner comedies -- Private Lessons (1981), Screwballs (1983), Spring Break (1983), where drinking was encouraged, pot-smoking was hysterical, wet t-shirt contests spontaneously erupted with an alarming frequency, while every guy tried to screw anything that moved and the gals, sadly, were only there to get screwed. Yeah, you know, the ones you wanted to go see while your folks dragged you kicking and screaming to see Ordinary People (1980). Again.

Kouf had already contributed to this glut with both The Boogens (1981) and Class (1983). Up the Creek -- originally co-conspired by Kouf, Jeff Sherman and Douglas Grossman, kinda brought up the rear for this kind of romp, as these horizontal-bop-fueled comedies tended to cycle around on the same surge 'n' fizzle schedule as their boon companion, the horizontal-bop-fueled body count movie. Here, to mix things up, the action would be moved outdoors as the film’s centerpiece would be a white-water raft race.

Louis would co-produce the film with his father, who guaranteed Orion he could bring the film in at half the proposed budget of $7-million if they’d let him do things his way. (Record scratch. They didn’t, and we’ll get into how in just a sec.)

To direct, the studio assigned them Robert Butler, a prolific director for TV, whose rare theatrical output was mostly for Disney -- most notably, the Dexter Riley (Kurt Russell) movies: The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes (1969), Now You See Him, Now You Don’t (1972) and The Barefoot Executive (1971).

And so, Butler had been directing in one medium or the other since the 1950s and was kind of long in the tooth to really tune into what the script and the film were trying to pull off. Kouf would later lament in an interview with Andre Dellamorte at Collider that “[Butler] was not a great comedy director; he missed a lot of jokes.”

For the cast, coming off of Night Shift (1981) and the smash hit Mr. Mom (1983), the studio really pushed hard for Michael Keaton for the lead role of Bob McGraw. But they never really got any further than his agent, and Keaton wound up in Johnny Dangerously (1984) instead. As for the second pick, they thought they had Steve Guttenberg locked-in until he abruptly backed out two days later to do Police Academy (1984).

Thus, Tim Matheson was a last second casting decision; but the only reason he was available at the time was due to the cancellation of Tucker’s Witch after only one season, which featured Matheson as one half of a husband and wife detective team with Catherine Hicks, who used her preternatural abilities to help them solve cases, which wasn’t quite as dumb as that sounds. Honest.

Rounding out our gang of misfits, Dan Monahan was in between shooting Porky’s (1981), Porky’s II: The Next Day (1983) and Porky’s III: Porky’s Revenge (1985), where he played Pee Wee, making him another solid genre vet as Max. (A trilogy I recently revisited and was kinda surprised at both how well it held up and how it had a few more ideas rolling around in its horny noggin’ than you’d think.) Sandy Helberg had a bit of an “in” for his role as Irwin, as he was married to Harriet Helberg, the casting director (-- as far as I know, they’re still together), but he wound up being one of the funniest elements of the film and was allowed to improvise and developed a few running gags.

And last but not least, we have Stephen Furst. It seems fitting that Up the Creek would have two Animal House alums -- Matheson (Otter) and Furst (Flounder). True, this cast was a little … ‘well seasoned’ to be doing this kind of flick by the time it was made, but their sense of camaraderie is rock solid and they all appear to be having a ball as they run through the familiar paces and plot points -- especially Furst, who finally got to ditch Flounder and play Bluto for at least one film. In fact, everybody appears so comfortable that Up the Creek comes about [--this--] close to crossing the self-awareness threshold and stumbled into self-parody.

For the snobs and villains, James Sikking was always a welcome sight. Jeff East is another familiar face, who also got his start at Disney and wound up playing Huck Finn in both Tom Sawyer (1973) and Huckleberry Finn (1974). He also played a young Clark Kent in Superman (1978) -- that's him racing the train, and would appear in a couple of notable horror films -- Deadly Blessings (1981) and Pumpkinhead (1988). Blaine Novak is probably best remembered for writing Peter Bogdanovich’s They All Laughed (1981), but he gives quite the inspired performance as Captain “Wile E.” Braverman, who takes a licking and somehow keeps on ticking as he is constantly blown up or inadvertently becomes the ammunition for an ersatz trebuchet. And I will assume Jonathan Hillerman owed someone, somewhere, a favor for the hot minute he appears in the picture.

As for the ladies of Vanity U, this wasn’t quite Jennifer Runyon’s first appearance as the “introducing” credit boasted. She had appeared in the soap opera, Another World, and had already appeared in the holiday slasher, To All a Good Night (1980). But most folks will probably recognize her as the girl in the rigged ESP test from the beginning of Ghostbusters (1984). Co-star Julia Montgomery had also previously appeared in a slasher, Girls Nite Out (1982), and would next appear in Revenge of the Nerds (1984), who partook in the notorious sex scene with someone she thought was her boyfriend only it was someone else behind the mask in the funhouse, and then fell in love with him because the sex was just that good. Wow. And wow again. Romy Walthall would be another familiar face on television in the 1980s, who also appeared in Howling IV: The Original Nightmare (1989) and Surf Ninjas (1993); and the quartet was rounded out by former Playboy Playmate and current Real Housewife of Orange County, Jeana Keough.

The film would be shot in and around Bend, Oregon, with most of the rafting action taking place on the Deschutes River between Aspen Park and the Lava Island Falls. Before cameras rolled, the cast was sent in two weeks early to learn how to raft on the whitewater without drowning themselves.

Several locations in town were used as well, including the Bend Woolen Mill, a local bar, where all our players first meet the night before the big race, scope out the competition, and Bob and Heather decide to sleep together, which, if you remember, is why he is currently getting his head kicked in by Rex and the Van Pattens.

But Bob recovers from this beat-down in time for the start of the two-day race. See, only the first five teams that make it to a certain checkpoint along the river will be allowed to race the next day; and, somehow, despite the rapids and the spectacularly failed efforts of the vengeful Braverman to sink them, and even though their raft was blown out of the water and sunk on two separate occasions by those Ivy frat-rats, our gang of misfits manages to patch things up, stay afloat, and survive long enough to snare the last flag -- thanks to Chuck.

Then, later that night, looking for a little payback, our boys sneak into the massive Ivy U encampment and destroy it rather ludicrously. But during the confusion, Irwin is captured by Braverman's rogue cadets and then staked out as bait for the others to find.

For, after all that head trauma accrued throughout the last two days of backfiring retaliations, the good captain is now, well, a few cans short of a six-pack; evidenced by his logic that there can be no winner of this race if there is no course, explaining why he just ordered his men to blow up the river. And, for some reason, he has enough C-4 to do it!

Meanwhile, Chuck manages to find Irwin and leads the others, after a nifty game of charades, to his eventual rescue. But our heroes barely make it back to their raft before the river goes ka-boom. Caught in the divergent flash-flood, our heroes are soon swept away by the angry torrent. Is this the end of our beloved boys of Lobotomy U? Well, I wouldn't bet on it...

For those of you who grew up with a VCR in the 1980s like me, Up the Creek probably won’t offer anything you haven’t already seen, countless times, but I honestly think there are enough tweaks and gonzo-performances to keep you entertained. And if the film has one secret weapon that provided a paddle whenever it got stuck, well, it was the dog.

With a vocal assist from animation legend Frank Welker, Chuck the Wonder Dog was portrayed by a pup named Jake, according to the closing credits. These credits also reveal he was trained by Steve Berens, who I’m sure did a lot, and kudos for his efforts, but Jake sure seemed to be a natural ham to me. The scene where he finds Irwin staked out, chases off Braverman, and steals the victim’s underwear as proof of life and takes it to Bob and the others, which can only mean one thing, says Max, “Irwin’s naked,” answers Gonzer, and only Chuck knows where he is, that bit destroys me every time I see it.

And the game of charades that follows to pinpoint that exact location between the dog and the others belongs in the Hall of Fame of such things and provided another sterling example that Up the Creek was much more interested in slapstick than sex. To the film’s betterment or detriment is, well, up to each individual viewer.

Mention should also be made of just how stunning, harrowing, and ambitious the white water rafting scenes are in this film. Credit to stunt coordinators Gene Hartline and Chris Howell for keeping everyone in one piece. It’s kinda easy to tell when the stuntmen took over, sure, especially during the climax, but not always.

James Glennon had been an assistant or a camera operator on things ranging from The Conversation (1974) to Breaking Away (1979) to Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), and this would basically be his first time as a cinematographer; but he captures the chaos of traversing the rapids rather brilliantly, getting the audience right into the middle of things that you almost feel wet when the river finally calms down.

And, holy hell, that last stunt, when a barely conscious Braverman triggers the explosives, damming the river, which diverts the raging water through Tozer’s lodge, obliterating it and dumping our merry band of miscreants back into the river between Ivy U and the finish line? I think it rivals the destruction of the Douglass home at the end of Spielberg’s 1941 (1979) for sheer spectacle in a practical FX sense. And after surviving that, I believe it's only fitting that Dean Birch finally gets his victory for LePetomane.

But things didn't run completely smoothly up in Oregon. Originally, the Arkoffs wanted to hire local teamsters to work on the film because it would’ve been cheaper but Orion insisted on sending in their own teamsters, which jacked up costs considerably. (And this kind of math explains why Orion also went bankrupt by 1991.)

The production also ran into some troubles with the locals during the two-and-a-half month shoot. Affairs happened, and engagements were broken according to Helberg in a making of documentary on the Kino Lorber release of Up the Creek, which caused some hard feelings. And in an online article I found from The Source Weekly (May, 2010), credited to “The Staff,” which looked back on the production, it mentions how several local establishments in Bend refused service to anyone involved with the production over perceived rude behavior.

“Things got off to a bad start,” according to the article, “as the films' producers, director and others involved in the making of this ‘masterpiece’ went around town treating people like they were essentially inferior … they were so arrogant and patronizing.” Apparently, the writer of the article was cast as an extra in the film back in ‘83, too, but after a few days they soon grew tired of “putting up with the endless hurry-up-and-wait filming proceedings,” walked off the location, and never returned.

After filming wrapped at the end of June, 1983, to put an end to these hostilities, the production promised to juice-up the city’s annual Fourth of July fireworks display on Pilot Butte to make amends. But, according to the article -- that admittedly comes off just a tad bit biased, the show “was a colossal dud. That's dud as in an insipid, lackluster show that ended with some dynamite ka-boom and a huge fire breaking out on the butte.” And I guess if there was any consolation, the production left behind all the rafts used in the film, selling them off to a local entrepreneur. And so, for the next few summers, unwitting renters could toodle down the Deschutes in a raft with LePetomane, Texas State and Ivy University stenciled on the side.

Now, another trademark of 1980s cinema is you had to have a song with the name of the movie in it. Here, Cheap Trick got the nod for “Up the Creek,” a fairly raucous number that anchored the soundtrack album, which featured tracks by Heart, the Beach Boys, Kick Axe, and a couple of cock-knocking ballads by Shooting Star. I’m telling ya, that “Get Ready Boy” track is quite the corker.

When Up the Creek was finally finished and released in April, 1984, somewhat surprisingly given the subject matter, it received some somewhat favorable reviews. Both Siskel and Ebert gave it a thumbs up. Said Ebert, “The film belongs to an honorable movie tradition, the slapstick comedy. It is superficial, obvious, vulgar, idiotic, goofy, sexy, and predictable. Those are all, by the way, positive qualities -- at least, in an Undergraduate Slob Movie.” Some reviews weren’t as kind, but the overall gist was if you had to see one of these damnable things, you could do a lot worse than this one.

Up the Creek would go on to earn nearly $12-million at the box-office. And while it didn’t lose money, it failed to light things up like Police Academy -- $81-million, Revenge of the Nerds -- $42-million, or Bachelor Party (1984) -- $39-million, did that same year. It might’ve done better if it was released during the summer, but with Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Ghostbusters and Gremlins (1984) all looming, maybe not. I mean, I think it was already getting squeezed by Romancing the Stone (1984) and Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter (1984), which also came out in April that year.

The family Arkoff would next tackle Hellhole (1985), a fairly risible horror film about a woman trapped in an insane asylum with the man who was trying to kill her. After that, Louis would team up with Debra Hill -- Halloween (1978), The Fog (1980) -- for a series of loose remakes of AIP's back catalog for Showtime under the umbrella of Rebel Highway (1994) -- with the caveat that the chosen filmmakers could do whatever they wanted as long as they did it within the allotted budget of $1.7 million, which included updated takes on Roadracers (1959), Shake Rattle and Rock! (1956), Girls in Prison (1956), Motorcycle Gang (1957) and Cool and the Crazy (1958) among others by the likes of Joe Dante, Robert Rodriguez, John Milius and Alan Arkush.

Donna Arkoff Roth, meanwhile, would also prove a chip off the old man's block by producing a string of her own modest hits, including Benny and Joon (1993), Grosse Pointe Blank (1997) and 13 Going on 30 (2004), and would team-up with her dad to help in the production of the slightly gone awry remake of The Haunting (1999). And before he passed away in 2001, the last thing Samuel Z. Arkoff would ever produce was another string of direct to video remakes with Louis, Teenage Caveman (1958), The She Creature (1956), Earth vs. the Spider (1958), The Day the World Ended (1955), and How to Make a Monster (1958), bringing and end to his long and storied career.

Circling back to our featured feature, stranded in VHS purgatory for years and years after its theatrical run, Up the Creek finally made the digital jump back in 2012 through MGM's Limited Edition Collection, meaning a no frills, made-on-demand DVD-R like the Warner Archive discs. But then Kino Lorber released a slightly more affordable DVD and Bluray in 2015 and I snatched it up quick to replace my worn out VHS copy because, sometimes, nostalgia tends to stomp a mudhole in your logic circuits, leaving them completely goobered-up and stranded -- hell, no need to spell it out, you know where, without a paddle.

Yeah, this wild and raunchy yarn of beer and boobs -- both kinds -- and a whitewater raft race was, at the ripe old age of 13-and-a-half, the very first R-rated film Yours Truly managed to bluff his way into. And don’t tell my mom, okay? She still doesn’t know that I’ve never seen Splash (1984).

Now. Did this first encounter and rite of passage have any influence on my positive reaction to this total dingus of a film? Has it clouded my judgment? Well, it probably didn’t hurt. What I do know is when I first saw it, Up the Creek made me laugh. Hard. And every time I’ve watched it since, it still makes me laugh just as hard. Every time. Get set to get wet, indeed.

Originally posted on January 21, 2000, at 3B Theater.

Up the Creek (1984) Orion Pictures / EP: Louis S. Arkoff, Samuel Z. Arkoff / P: Michael L. Meltzer, Fred Baum / D: Robert Butler / W: Jim Kouf, Jeff Sherman, Douglas Grossman / C: James Glennon / E: Bill Butler / M: William Goldstein / S: Tim Matheson, Stephen Furst, Dan Monahan, Sandy Helberg, Jennifer Runyon, Jeff East, Blaine Novak, James B. Sikking

No comments:

Post a Comment