“I know my story sounds fantastic, but it is true.”

Way, way back in Fourteen Hundred and Ninety-Two, when Columbus sailed the ocean blue, history shows he steered the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria into what would come to be known as the Sargasso Sea. Named for the sargassum -- a dense, floating blot of aquatic vegetation that marks its boundaries, this nebulous body of water has earned itself a rather insidious reputation over the centuries since Columbus first mistook these masses of seaweed as a good omen that land must be near.

Prone to deadly calms that left sailing ships stranded indefinitely, the Sargasso soon earned itself several nicknames, including The Sea of Lost Ships, as several salty sea tales of massive graveyards of vessels, swamped in the muck, their holds full of gold, with their skeletonized crews still waiting for a wind that would never, ever come just waiting to be plundered, began to surface.

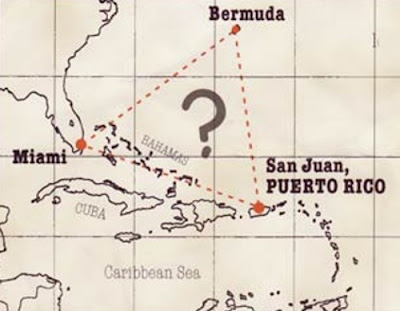

And as wind power gave way to steam, ships still managed to venture into these waters only to never be heard from again. It didn't help matters that this area was also prone to magnetic disturbances known to send compasses spinning or pointing to true north instead of magnetic north; and dead spots, where all radio communications were disrupted or neutered, which led to another nickname -- The Sea of Fear, as the troublesome concentration of these maritime disasters began to define itself a little more clearly; an area that was roughly demarcated by a line drawn from the southern tip of Florida to the island of Bermuda, then south to Puerto Rico, and then back along the Bahamas to Florida.

Even as man took to the sky this new means of travel brought no immunity as several airplanes met the same unknown fate above as their water borne brethren below somewhere over the Sargasso. However, most of these instances were isolated with plenty of plausible explanations for these abrupt disappearances.

But then, on December 5, 1945, five TBM Avenger torpedo bombers left the naval air-station at Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, on what was supposed to be a routine two-hour training flight. Designated Flight-19, it was under the command of Lt. Charles Taylor, a combat veteran, who had served in the Pacific campaign on the carrier Hancock. And while the rest of the pilots and crew were trainees, they were far from their first flights. In fact, this was to be their last training mission before graduating. And after a slight delay, the flight departed; and as the planes formed up the weather was clear and favorable, the sea moderate to rough.

Again, this practice bombing run was nothing any of these pilots hadn't done before. And once they cleared the runway, another batch of trainees would launch to run the exact same exercise -- somewhat ironically, a triangular course, just as another group was ahead of them and already well on their way to Chicken Shoals.

But once Flight-19's bombing run was successfully completed, something strange happened. It began with pilot to pilot radio transmissions, asking for a compass heading. This chatter continued, growing more agitated as it became apparent Flight-19 was off course. More radio calls inferred the entire flight's compasses were malfunctioning, and no one could get a proper bearing or heading. More confused transmissions followed, desperately trying to get fix on their location; one thinking they might be over the Florida Keys, another fearful that they were now somewhere over the Gulf of Mexico.

On the ground, all efforts to triangulate the flight's location failed. Radio contact with the squadron was spotty and intermittent, and as the crisis dragged on it suddenly stopped. Still, the plane to plane chatter continued, arguing over which direction to head as Taylor kept them circling ever eastward, while the others begged him to head west. At one point, several land-based radio stations were able to fix Flight-19's location as nowhere near Florida but north of the Bahamas. But before this could be confirmed, contact was lost.

As the weather started to deteriorate and the sun began to set, with the planes now dangerously low on fuel, a distraught Taylor radioed how the sea didn't look right, and was awash in a strange light. Then, the last transmission from Flight-19 was received: "All planes close up tight ... We'll have to ditch unless landfall ... When the first plane drops below 10-gallons, we all go down together."

Despite a massive air and sea search covering nearly 250,000 square miles, no traces of Flight-19 or the 14 men who manned the five planes was found. No debris. No oil slicks. Nothing. They simply vanished. Now, this flight was one man short since a Corporal Allan Kosnar was excused from duty because, according to legend, he had felt a "strong premonition of doom" and begged off sick. A Naval board of inquiry initially laid the blame on Taylor, but this was later revised and the official reason for the disappearance was "cause unknown." Seventy-five years later, they still don't know what happened for sure. But back in 1945, the Sargasso had earned itself another new name: The Bermuda Triangle...

The first allegations that something screwy was going on in the waters east of Florida first saw print in September, 1950, with an article by Associated Press reporter E.V.W. Jones, as a follow-up to the recent disappearance of The Sandra -- a 175-foot freighter, loaded down with pesticides and on its way to Venezuela from Savannah, Georgia -- that seemingly vanished without a trace in June, 1950, which tied several unsolved maritime disasters, including Flight-19, to the area.

In 1952, Fate Magazine published an article by George Sand, "Sea Mystery at Our Back Door,” which was the first to note the (now standard) triangular shape of the troubled area, and was the first to suggest a preternatural element as the root cause to all of these strange disappearances.

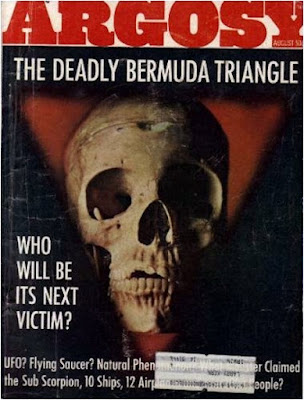

A decade later, Vincent Gaddis' "The Deadly Bermuda Triangle" saw print in the February, 1964, edition of Argosy, which further expanded on the pattern and causes of these disappearances. Said Gaddis, “The Bermuda Triangle underlines the fact that despite swift wings and the voice of radio, we still have a world large enough so that men and their machines and ships can disappear without a trace.” And though Gaddis would later publish his theories in a book, Invisible Horizons (1969), the Bermuda Triangle didn't really strike a chord with the masses until Charles Berlitz came along.

As the legend goes, gonzo author and noted linguist Charles Berlitz first became interested in the Triangle phenomenon at a travel agency in the late 1960s, when he became intrigued by several customers who adamantly refused any mode of travel through the dreaded area. That, however, was not quite true.

Born in New York City in 1913, Berlitz, fluent in four languages before the age of three, after graduating magna cum laude at Yale, where he pushed that number of languages to over 32, got into the family business, teaching at the famed Berlitz School of Languages, which was founded by his grandfather, Maximilian, in 1878.

With America's entry into World War II, Berlitz enlisted and found his way into the Army's Counter-Intelligence Corps. Once the war ended, Berlitz stayed in the military for nearly 13-years as a reservist. He also returned to teaching, eventually taking over the stewardship of several branches of the Berlitz school, where he pioneered the use of records and tapes in learning a second (or third or fourth or 33rd) language, and then took over Berlitz Publications until it was sold to a rival publishing house in 1967.

From there, Berlitz abandoned linguistics and went full bore into the world of ancient civilizations, underwater archeology and the paranormal; more specifically, locating and proving the existence of the lost continent of Atlantis, and later, getting to the bottom of the deadly occurrences inside the Bermuda Triangle.

As a child, the author was fascinated by ancient languages, particularly hieroglyphics, which fueled a lifelong obsession to “learn something about the origin of languages.” A firm believer in Ancient Astronauts and alien visitations since the dawn of man, Berlitz's first two books, The Mystery of Atlantis (1969) and Mysteries from Forgotten Worlds (1972), delved into these theories and the possible effect and influences these *ahem* ‘visitors’ had on some of these infamous "lost civilizations,” echoing the work of Erich von Däniken's Chariots of the Gods? (1968).

From Roy Stemman’s Visitors from Outer Space (Chris Foss, 1976).

“If planes, ships and people are being kidnapped, especially from the Bermuda Triangle, by UFOs or by other means, an important factor of any investigation should be the consideration of a possible reason or reasons,” postulated Berlitz. “Some researchers have suggested that intelligent entities, light-years scientifically advanced over the comparatively primitive peoples of Earth, have been engaged throughout the centuries in observing our progress and will eventually intervene to prevent us from destroying our own planet.

“On the other hand,” Berlitz continues, “it may be that there exists, in the vicinity of the Bermuda Triangle and certain other nodal locations of electromagnetic gravitational currents, a door or window to another dimension in time or space through which scientifically sophisticated extraterrestrials can penetrate at will but which, when encountered by humans, would represent a one-way street from which return would be barred by alien force. Many of the disappearances, especially those involving entire crews of ships, suggest raiding expeditions, ranging from collecting human beings for space zoos, exhibits of different eras in planetary development or for experimentation.”

Around this time Berlitz also had his alleged encounter at the unknown travel agency, which determined the topic of his next book. But most of this interest, however, seems to stem from his time as a reservist, where he served as an investigative officer for the Army Air-Corps when Flight-19 disappeared. And after compiling all of his research, Berlitz believed that "the people and planes and ships that have reportedly disappeared in the Bermuda Triangle have been victims of some sort of electromagnetic disturbances that cause them to disintegrate and fall into the sea."

And his speculative exposé on this and other theories, The Bermuda Triangle (1974), sold more than 14-million copies worldwide, feeding the voracious appetite of the crypto-addled public of the 1970s, who had gone completely bonkers over UFOs, Bigfoot, ghosts, and psychic whammies, and almost single-handedly made the notorious area of water a household name and caused a massive dip in Bermuda's tourist trade.

“This area -- referred to as the Bermuda Triangle -- occupies a disturbing and almost unbelievable place in the world’s catalogue of unexplained mysteries,” declared Berlitz in the opening salvo of his book. “It is here that more than 100 planes and ships have vanished into thin air, most of them since 1945, and where more than 1000 lives have been lost in the past 26 years, without a single body or even a piece of wreckage from the vanishing planes or ships having been found … In no area outside the Bermuda Triangle have the unexplained disappearances been so numerous, so well-recorded, so sudden, and attended by such unusual circumstances, some of which push the element of coincidence to the borders of impossibility.”

At some point during all of this, Berlitz also hitched himself onto noted prognosticator and self-proclaimed mystic Edgar Cayce's bandwagon and tied his two obsessions together, claiming Atlantis was located inside the Bermuda Triangle -- even claiming to have found a massive pyramid on the ocean floor near Bimini. But a reviewer for TIME Magazine countered, saying the author "takes off from established facts, then proceeds to lace his theses with a hodgepodge of half-truths, unsubstantiated reports and unsubstantial science.'' And Naval historian Eliot Morison called Berlitz's book "a load of hoey,” adding most of the documented disappearances didn't actually happen inside the Triangle or could easily be explained by more normal causes.

But even as the Washington Times tagged him as "the de-facto expert on weird phenomena,” Berlitz was just getting started. Flooded with more eye-witness testimonies after his first book hit big, he immediately published another on the Triangle, Without a Trace (1977), followed by yet another exposé on some deadly Naval exercises that took place in these very same waters, The Philadelphia Experiment (1979), co-authored by William Moore, which alleges the US Navy tested some top-secret high-powered generators to make a "magnetic field" powerful enough to render a destroyer invisible that went completely awry, causing the boat to shift between dimensions, leaving several crewman dead, melded into the hull, while others kept blinking in out of this known existence. And as the 1970s came to a close, Berlitz once again stirred up the notion that the government was covering up the existence of aliens with The Roswell Incident (1980).

Meantime, producer and director Charles E. Sellier Jr. -- probably best known to the masses for the ruination of Christmas with his controversial but, in the end, harmless holiday slasher, Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984), was quietly becoming one of the patron saints for a certain niche of shlock cinema. For we children of the 1970s remember him more for a rash of faux docs on cryptids and other strange phenomenon like The Mysterious Monsters (1975) -- which gave five year old me one of thee worst case of the drizzles, The Amazing World of Psychic Phenomena (1976), and Beyond and Back (1978), which he unleashed on the public and drew the ire of both noted film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, along with his eccentric historical docudramas, In Search of Noah's Ark (1976) and The Lincoln Conspiracy (1977) -- half of which I remember seeing in the theater. The others used to be late night staples on the Supestations before they all chucked them for more mainstream programming. (Altogether now, BOO!, Superstations. We said, BOO!)

Charles E. Sellier Jr.

So to say Sellier Jr. was a bit obsessive on the mysterious and unexplained would be a bit of an understatement; but he found a kindred spirit with fellow filmmakers Rober Guenette -- The Man Who Saw Tomorrow (1981) and James Conway -- Hangar 18 (1980), who all found distribution through Sunn Classic Pictures, a subsidiary of Schick Enterprises, who had expanded beyond disposable razors. Based out of Salt Lake City, Sunn Classic was kind of a throwback to the old barnstorming and hucksterism road-show days of Dwain Esper and Kroger Babb, moving from city to city, with over-saturation advertising campaigns to lure people into the theaters, where it would have a limited run to add even more urgency before moving on and starting the process all over again.

As 1978 rolled around, Sellier Jr. and Conway managed to get the film rights for Berlitz's book and set out to adapt it to film in their usual docu-drama style. Now, what I always loved about these kinda movies and books on this type of whackadoodle subject matter is they all tended to follow a fairly familiar pattern. First comes an introduction to what mystery we're investigating, then comes the dramatic recreations of infamous incidents and firsthand testimonials, followed by a token attempt to show all the possible rational explanations for these strange phenomena before we get to the best parts, where the crackpot theories roam wild and free.

In The Bermuda Triangle (1979), director Richard Friedenberg and scriptwriter Stephen Lord stick to this gonzo approach, playing rather loosely with the facts for ... uhm, dramatic purposes, and throw in everything but Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster. And while Flight-19 is a centerpiece (-- and it should be specified that this was Berlitz’s version, which is highly embellished with a few more supernatural twists and turns, 'natch), it begins with Christopher Columbus' encounter with a series of strange "fireballs" in the sky near Bimini; then a ghostly encounter with the Mary Celeste and the Flying Dutchman; then the disappearance of the U.S.S. Cyclops.

These, along with about a dozen more encounters in the Triangle, by sea and air, related by those who survived and speculation over what happened to those who did not, round the film out. Highlights include:

A rather unintentionally hilarious segment about a dimensionally-displaced barge; a plane passenger's harrowing close encounter with a space-time vortex; an airliner that ceased to exist for 12-minutes; a rather creepy segment on Carolyn Cascio, who, on June 7, 1969, was piloting a small plane near the Grand Turk Islands, where she and her passenger were apparently caught in a time bubble, circling back and forth, unable to land because whenever / wherever they are / were the airport hadn't been established yet, even as the confused radio-operator in the tower below could see and hear them circling overhead until they disappeared into the clouds and were never heard from again. Things even get a little sinister when some of these surviving eye-witnesses die under dubious circumstances for, dare I say, knowing too much.

As far as the theories go, well, once pilot-error, underwater earthquakes, water-spouts, and leftover mines are written off due to the lack of physical evidence, followed by some heated conjecture between several oceanographers with out-RAY-geous French accents over (sacré) blue holes (-- essentially giant whirlpools), the film starts thinking outside the box -- and these ideas are all bone-headedly magnificent.

One of my favorites is the claim that it all boils down to Atlantis -- namely a powerful crystal that, when not harnessed properly, is prone to violent discharges of energy that not only destroyed and sunk the ancient civilization but is still popping-off from the ocean-floor to this very day like some ersatz death-ray -- represented by pilfered and spliced-in footage from George Pal's Atlantis: The Lost Continent (1961).

Dimensional rifts caused by all that magnetic interference is also given some play, as is a wild reenactment of the "failed" Philadelphia Experiment, where the U.S.S. Eldridge is super-charged for naught and all her sailors turned into ghostly, intangible lab-rats. But the film's own favorite pet theory is a UFO connection -- which I'm sure had nothing to do at all with the release of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) the year before, claiming there's a secret underwater alien base near Puerto Rico, who have been picking off ships and planes to keep it a secret since the 1800s.

This notion even leeches into the Flight-19 segment, with additional radio chatter about a silver object and strange lights before all communications are lost. (Again, Flight-19 plays a role in Spielberg's film, as well. Coincidence? I think not. Nope. Nosiree.) In fact, the last third of the movie is dedicated to these Unidentified Flying -- no, wait, sorry, Underwater Floating Objects, even going so far afield for another hilarious dramatization of Captain Thomas Mantell's fatal encounter with a UFO over Fort Knox, Kentucky, in 1948, which, according to my map, is nowhere near Bermuda. We also learn that these aquatic alien invaders have an aversion to salsa music. Go figure.

Tying all of these spooky and kooky tales together is Brad Crandall, who serves as our omnipresent moderator and guide. Crandall's career began as a proto-shock jock for WNBC, New York, in the 1960s. In the 1970s he sort of became a freelance narrator for films like this one, making his deep and authoritative voice as familiar to me as Percy Rodriquez, Ernie Anderson or Don LaFontaine. The rest of the acting by the cast of mostly unknowns in the reenactments is serviceable enough, as is Friedenberg's direction of the same.

Often overlooked in these things, but John Cameron's score kinda quietly glues the film together; making the eerie and ominous even creepier, the rousing more bombastic, or capturing the strange mix of dire danger and gob-smacked awe of the impossible things being seen and heard by all these alleged witnesses. As for what we saw they said they saw, the FX -- credited to Doug Hubbard, is grounded in the decade that spawned it but is actually quite good once you consider the budget; though thinking on it about three-quarters of his job was just adding a green-filter to the camera lens. Still, the miniatures and pyrotechnics were rather spiffy.

Obviously, Berlitz's book is part truth wrapped-up in a ton of bullshit. But I do believe it was sincere bullshit. Sellier's film adaptation, of course, is pure exploitation, beating the evidence and the sincerity around the head and neck with the three Fs: faulty, fraudulent and fabricated. "Science does not have to answer questions about the [Bermuda] Triangle because those questions are not valid in the first place," said Dr. Buzzkill in an episode of NOVA (June, 2006) dedicated to debunking this particular myth. "Ships and planes behave in the Triangle the same way they behave everywhere else in the world."

The United States Coast Guard does have an official file on the subject (5729) -- again, according to Berlitz, but their official line on the Bermuda or Devil’s Triangle is that “its an imaginary area located off the southeastern Atlantic coast of the United States, which is noted for a high incidence of unexplained losses of ships, small boats and aircraft.” Yeah. It's been said that if you took a global map and drew a triangle with the same dimensions as the Bermuda Triangle and placed it anywhere else that was blue it would show that just as many ships and planes disappeared in the new triangle as the old, making it no more or less dangerous than anywhere else -- even though anywhere else never got its own home version board game from Milton Bradley. (Take THAT, Dr. Buzzkill.)

And while I don't necessarily believe in things like the Bermuda Triangle, I like the idea of it existing -- and the same goes for Bigfoot, lake monsters, UFOs and ghosts, if that makes any sense. And I love books and documentaries based on them even more, with The Bermuda Triangle being a particularly riveting favorite both in print and film. Yes, even though the majority of it is bullshit -- I know it, and you know it, I love this flick unconditionally because sometimes ... Sometimes you simply just don't care and just simply run with it to see where the bullshit takes you because the bullshit is the best part. And if that doesn't compute for you, well, I'm sorry. Truly sorry.

And one more thing before I once again set sail to parts unknown, while a lot of these old paranormal and cryptid-docs managed to eke out a VHS release they still have yet to make the digital leap; and I would hope that someone, anyone, would rectify that as soon as possible.

Originally posted on July 26, 2015, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

The Bermuda Triangle (1979) Schick Sunn Classics / P: Charles E. Sellier Jr., James L. Conway / D: Richard Friedenberg / W: Stephen Lord, Charles Berlitz (book) / C: Henning Schellerup / E: John F. Link / M: John Cameron / S: Brad Crandall, Vince Davis, Anne Galvan, Robert Magruder, Tom Matts