We

open in a place called Mother’s Tea Room, which is a bit of a

purposeful misnomer, I'd wager -- if I’m reading the film’s tea leaves

right, as a waitress sits and knowingly serves alcohol to a group of

under-age college co-eds (-- among them Raquel Welch and Norm

Grabowski), and then instructs them on what to do with their drinks when

a certain light over the bar starts flashing, meaning a raid is

imminent. And then this ersatz speakeasy really gets to rollin’ when the

owner chases the current act offstage and introduces the next one,

Charlie Rogers.

Now, here, we quickly deduce that Rogers (Presley) is from the wrong side of the tracks, has a fairly sizable chip on his shoulder, and a very short fuse when his first number, “Poison Ivy League,” really takes the piss out of the unruly, privileged "college boys" he sees seated before him. And when you couple that vibe with the fact he also brazenly hit on their girlfriends between each verse, a trio of collegians decide it's time to knock this smart-mouthed singer down a peg or two.

Easily goading their hot-tempered target into a fight out in the parking lot, at three against one, these odds may seem unfair but Rogers quickly breaks out his mad karate skills and easily dispatches all of his assailants, seriously injuring one of them. Alas, sensing trouble, that waitress, Marge (Staley), had called the cops, who take in the carnage and then take Rogers into custody.

After spending the night in the clink, Marge pays his fine and bails him out in the morning. Seems she has fallen hard for Rogers and is trying to set the hook in deep; but our boy ain’t interested in being tied down or beholden to anyone. “Just because you bailed me out doesn’t mean you own me,” says Rogers, who punctuates this point by hopping on his motorcycle and leaving poor Marge in the dust with nary a backward glance.

Thus and so, it’s time for our aimless drifter to once more move on, who dons his leathers, straps all of his worldly possessions onto his bike, and then hits the open road, where he spontaneously bursts into the song, “Wheels on My Heels.” Now, when this song peters out, Rogers comes upon a trio of people motoring along in a jeep. Spotting a pretty girl riding in the back, our wayward lothario immediately makes a pass at her -- all at about 50mph.

But the girl's belligerent father, Joe Lean (Ericson), doesn't like this greaser making the goo-goo on his little girl, Cathy (Freeman), and promptly runs the motorcyclist off the road in a fit of temper, much to the consternation of his daughter and his second passenger, his boss, Maggie Morgan (Stanwyck).

Luckily, Rogers isn’t seriously injured. His bike on the other hand is nearly totaled. And by way of an apology, Maggie not only offers to pay for all the damages, including replacing his busted guitar, but also gives this handsome stranger a job as a temporary roustabout for her carnival in spite of Joe Lean’s vehement protests. Rogers accepts, mostly to piss Joe off, but makes it perfectly clear he will only stick around long enough for his bike to be repaired and then he’s gonesville.

With that settled, Rogers quickly gets to work by first learning the difference between a >circus< and >>carnival<< and the Secret Code of Carnies (-- which is very similar to Ape Law from The Planet of the Apes (1968) when you really get right down to it). He also quickly ingratiates himself to his fellow roustabouts, putting rides together, and the rehearsing performers along the midway (-- including Billy Barty and Richard Kiel), picking up the lingo as he goes, learning the tricks of the trade, and avoiding both Joe Lean and a certain grab-fanny fortune teller (Langdon) as much as possible. In fact, he’s adapted so well Maggie's convinced the carnie sawdust has already infected his veins so deeply he’ll soon sign on permanently.

But Rogers still insists he’ll be leaving as soon as the parts come in for his bike. (About a week.) Meantime, he also works hard to charm Cathy; but her constantly cock-blocking father and her dedication to the Carnie Life seems to always get in the way. And on top of all that, the carnival itself is in some serious trouble.

Under the financial pressure of a recent lawsuit and personal injury settlement, whose root cause was a malfunctioning ride that was under Joe Lean’s direct supervision, who was too drunk to see that it wasn’t stitched together properly, Maggie is currently way behind on the loan payments to keep her operation going. Of course, this chain of events is what set Joe off on his current self-destructive, bourbon-fueled rage spiral despite Maggie’s assurances that it's all in the past and he needs to move on. And she is willing to help him with this, if he’ll let her.

But all assurances aside, with foreclosure imminent, this one-lung operation is currently on its last leg. And only a miracle, like, say, oh, I don’t know, maybe if Rogers, in his effort to get a shot at Cathy, suddenly bursts into song on several occasions as he serenades her down the midway, drawing a sizable crowd in his wake, will finally turn things around...

After the middlin’ box-office and critical panning of both Flaming Star (1960) and Wild in the Country (1961), Colonel Tom Parker, manager, technical adviser, huckster, chiseler, and grifter extraordinaire, was able to use these back-to-back disappointments to convince his top client and massive cash-cow that it was obvious nobody wanted to see him act as another character in a dramatic role, and only wanted to see him be, well, Elvis Presley. And in Parker’s defense, the numbers backed him up -- at least to a certain degree. The musical comedy G.I Blues (1960) had raked in $4.3 million while Wild in the Country, a drama, brought in $2.7 million and Flaming Star, a western, barely broke over $2 million.

Thus, from there, for all intents and purposes, with one notable exception that we’ll be addressing in a second, Presley’s chance at a legit acting career was in trouble as he officially entered the Travelogue or Action-Man phase of his Hollywood journey, where he would basically play himself plugged into different playsets with the appropriate accessory pack over and over and over again; be it a boxer in Kid Galahad (1962), a Sheriff in Follow that Dream (1962), or, to get really meta, playing himself as a movie star based on himself in Harum Scarum (1965).

Screenwriter Allan Weiss was responsible for the majority of the scripts during this transitional period -- Blue Hawaii (1961), Girls! Girls! Girls! (1962), Fun in Acapulco (1963), and cemented the formula of slapstick, traveling-matte shenanigans, and a song every seven minutes. Quick and cheap and all according to producer Hal Wallis’s specifications. “Wallis [purposefully] kept the screenplays shallow,” said Weiss in a later interview for Peter Guralnick’s exhaustive, two volume biography on Presley, Last Train to Memphis: The Making of Elvis Presley and Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. “I was asked to create a believable framework for twelve songs and lots of girls” and not much else.

And while these films didn’t amount to much critically speaking they were still making a ton of money for both Parker and his client. At the time, Presley was being paid $200,000 per picture upfront plus 50% of the profits -- netting them about a half million per movie, of which Parker, as his manager, received half. Now, that back-half amount only counted what profits were left after all other production and advertising costs were recouped by the studio first. And so, Parker was constantly negotiating with several other Hollywood studios for a new contract, seeking a million dollar payday per-picture deal upfront. And until that deal was secured, Parker went out of his way to keep production costs down by any means necessary to reap all he could off the back-end of that deal

Of course, Wallis was the one who first imported Presley into motion pictures and inked him to that first contract for Paramount with Love Me Tender (1956), but he allowed Parker to loan Presley out to other studios as well -- mostly to let Parker be someone else's problem for awhile, including United Artists and MGM, which netted audiences It Happened at the World’s Fair (1963) and Viva Las Vegas (1964), which proved both a critical and commercial success -- in fact, it would be Presley’s highest grossing picture to date.

Now, Parker hated Viva Las Vegas with a passion for myriad and mostly petty reasons. Sure, producer Jack Cummings and director George Sydney had run circles around their “technical adviser” during the production, ignoring all his constant demands and meddling over how Sydney was favoring Presley’s co-star, Ann-Margret, too much and was allowing her to steal the movie. But the real reason Parker was so apoplectic over the production was all the money Cummings and Sydney and the studio were lavishly “wasting” on Viva Las Vegas, which went way over its allotted shooting schedule, and went way, way over budget, and cut way, way, way too much into Parker’s share of the profits.

Not wanting something like this to ever happen again, and still owing MGM two more pictures, ever the mercenary, Parker quickly struck a deal with Sam Katzman’s Four Leaf Productions to produce Kissin Cousins (1964) and Harum Scarum for MGM to distribute. Katzman and Parker were of like minds when it came to filmmaking: quick and cheap and done in ten days or less. And in Katzman’s case, sometimes five days or less. From there, all you gotta do is do the crooked math. Viva Las Vegas was an eleven week shoot with a budget estimated just south of $2 million. Kissin’ Cousins was completed in just 15-days on a budget of $800,000 -- over half of which went to Parker and Presley upfront. Thus and so, even though Viva Las Vegas technically made more money, Kissin’ Cousins made more of a profit for Parker first and Presley second. And to add even more insult to injury, Kissin’ Cousins was shot after Viva Las Vegas had wrapped but still beat it into theaters.

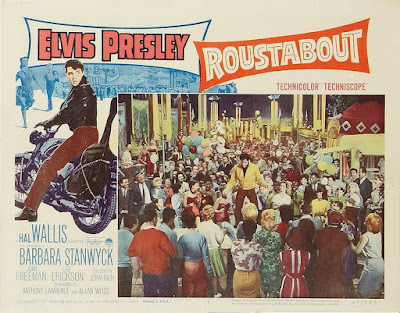

With that, Parker had successfully navigated his way around this perceived bump in the road. And while he was satisfied that things were back on track for their next scheduled feature with Wallis and Paramount -- Roustabout (1964), the master schemer was also starting to openly worry that he and Presley might no longer be on the same page.

On a personal level, at the time, Presley was kind of in a bad place. His affair with Ann-Margret had just both blown up in the papers and then subsequently imploded, which was followed by a massive fight with Priscilla Beaulieu, hidden away back in Graceland, over this infidelity. This would explain why Presley had been basically hiding out in Las Vegas for several weeks before he reported to the RCA Studios to record the soundtrack for Roustabout, where, according to an apocryphal story, when he requested that his usual back-up singers, The Jordanaires, accompany him on the “Wheels on My Heels” track, this was shot down because it wouldn’t mesh with the narrative of him riding alone on a motorcycle. Where would they come from (on film), they asked. To which Presley snapped back, “The same damned place as the band!”

"Who was that fast-talking hillbilly sonofabitch that nobody can understand?” Presley would later eulogize over his derailed movie career. “One day he's singing to a dog, then to a car, then to a cow. They're all the same damned movie with that Southerner just singing to something different." But even before the end, Presley was becoming disillusioned with acting and Parker's choice of scripts. Sensing this as well, to appease his client, Parker told Wallis that Roustabout needed to be a throwback picture and the main character needed to be a little wilder, a little rowdier, in an attempt to recreate the rebellious spark of Presley’s movies of the 1950s -- Loving You (1957), Jailhouse Rock (1957) and King Creole (1958). But, as the website Cinema Romantico rightly points out, “Whereas that spark in the ‘50s was more a product of youthful swagger, in Roustabout it is brewed with anger.”

The production was actually first announced back in May of 1961, then under the working title, Right This Way, Folks; and as an ex-carnie himself, I’m sure it was a concept that was dear to Col. Parker’s most grizzled heart. And once it was back on the slate, Parker would shoot off dozens of memos to Wallis about how the carnie workers should be treated with respect on film, focusing on the pride they took in their work. As for Wallis, he had his own concerns with the picture, feeling his star was looking a little “pudgy, soft and jowly.” His character was supposed to be a “rough, tough, hard-hitting guy” after all. And something would have to be done about his hair, which Wallis thought looked atrocious in Viva Las Vegas, feeling it came off as a bad wig; and so, the producer demanded the studio take care of Presley’s trademark dye-job and pompadour for the duration of the Roustabout shoot. Parker agreed, and so would Presley.

“If you ain’t tough in this world, baby, you get squashed,” says Rogers, establishing early on that his character has little patience or room in his psychological make-up for any sentiment. Anthony Lawrence would join Allan Weiss as co-screenwriter on Roustabout, who set to work making those required changes, explaining away why Charlie Rogers comes off as a bit of an indifferent, self-serving dick, which the film ultimately fails to get to the heart of and unravel -- a tactical error that would completely torpedo the ending. And it should be noted that, as presented this way, Rogers’ interest in Cathy cannot be interpreted as being romantically motivated at all; and therefore, it’s nothing more than a blitzkrieg attempt to woo the girl into knocking-boots behind the hot-dog stand before this pathological loner once more moves on.

Sure, this hardened veneer breaks down a little when Cathy subs in at the dunk tank where her father works the crowd on a chilly night, and is sent plunging into the frigid water by a ringer from the local baseball team, who seems hellbent on drowning the poor girl. And when Joe gets caught trying to rig the game to stop the next plunge in spite of another bullseye, the ball-tosser threatens to call a cop over these shenanigans. And so, all he can do is watch helplessly as Cathy, who assures she’s fine when it's obvious she’s not, is sent plunging into the tank again.

Here, Rogers finally steps in on Cathy’s behalf, pushes Joe aside, takes over the stand, and physically restrains the pitcher from hitting the target. It soon comes to blows, and the booth is destroyed in the resulting melee. When it's finally over, calmer heads prevail thanks to Maggie until the customer can’t find his wallet, left on the counter, who then accuses Joe of stealing it during the ruckus. Thus, Joe gets arrested and is hauled off to jail. And with his biggest obstacle finally out of the way, Rogers, in not the wisest of moves, takes this opportunity for another shot at Cathy, which goes about as well as you’d think under the circumstances.

Meanwhile, Maggie runs into Harry Carver (Buttram), a rival carnival owner, who’s anxious to pick the bones of her show once it finally goes under and then fold them into his own -- especially a certain singer he’s heard about that’s been drawing crowds like bears to honey. But the demise of her carnival has been greatly exaggerated, says Maggie, who claims she’s about to sign on Rogers for the long haul and then all her financial problems will be over.

Meantime, after having his own chat with Carver, and rejecting an offer to come work for him for more money, Rogers searches what’s left of the dunk-tank booth in an effort to make amends with Cathy and eventually finds the lost wallet where it fell unseen, hung up in the bunting. And while this discovery would exonerate Joe immediately, Rogers decides to let the old man cool his heels for the night in jail, letting him sleep off his multiple-week bender, and get his act together, for Maggie’s sake, I think. Again, the film is a little unclear on the motivations, here.

The following morning, a service truck drops off Rogers’ repaired motorcycle just in time to deliver that recovered wallet to the cops and spring Joe. But! Due to some rather dubious circumstances, this is all postponed again when he’s goaded into riding one of the stunt-bikes in the centrifugal Wall of Death attraction. Here, Joe’s wallet flops out of his pocket as he throttles down when Maggie and Cathy demand he stops this nonsense before their star attraction gets hurt, which is then found and given to Cathy. And while Rogers admits he found the wallet the night before and tries to explain his rationale for the delay in turning it in, his actions were a clear violation of the Carnie Code and he is immediately ostracized.

This also earns him a rightful close encounter with Joe’s fist after Maggie gets him released. With that, Rogers packs up, leaves, and ultimately jumps shows, signing on with Carver, who funnels a lot of money to his new star and his production numbers (-- “Big Love, Big Heartache” wasn’t bad, but “Little Egypt” is the absolute worst). Of course, with Rogers no longer around, the crowds start drying up for Maggie as the weeks passed and now she’s officially being foreclosed on come tomorrow. When Cathy asks if there is anything she can do, Maggie says she already knows the answer to that ... Uh, movie? No. No she really doesn’t.

And that’s why here, right here, is where Roustabout completely falls flat on its face as Cathy goes to see Rogers perform at the rival show. He spots her in the crowd, they connect on some cosmic level or … something, because now they're magically in love with each other. At least that’s how we’re forced to read it once the song wraps, as Rogers not only quits Carver’s show but takes the money he'd earned there and infuses it into Maggie’s carnival, making him part owner and a carnie for life.

This. This is what I meant about those changes to the script completely backfiring on the movie, resulting in a nonsensical, slapped and dashed happy ending that makes little sense and isn’t really earned in any way. It just happens because the script says so. As I also mentioned earlier, there isn’t much of a romance between Rogers and Cathy. In fact, I would say there is some dispute as to whether his efforts were to just get another “notch on his belt” or to knowingly piss off Joe Lean even more by having sex with his daughter. Sorry, the verdict’s still out on that one.

It didn’t really help that Presley couldn't really get anything to spark with Joan Freeman on screen. Apparently, Freeman was a little nervous around her co-star and his ever present entourage and tended to disappear into her trailer between takes. She's fine, it's just that their "romantic" arc is a total flatline. As her character’s father, Leif Ericson was a solid actor but the script kept him stuck at being angry or drunk or both. There are hints that Maggie has feelings for Joe but, once again, the script goes nowhere with this and Joe’s story arc is basically left unresolved.

But! It should be noted that a lot of these subplots -- hell, the main

plot, too, might’ve been left to die on the vine because there simply

wasn’t time to film anything to expand on them since Parker’s meddling

had managed to chop two whole weeks off the scheduled 8-week shoot. This

was all just irrelevant collateral noise to move the film from song to

song after all. No more, no less. And if the film didn't make any sense, damn the torpedoes and full speed ahead.

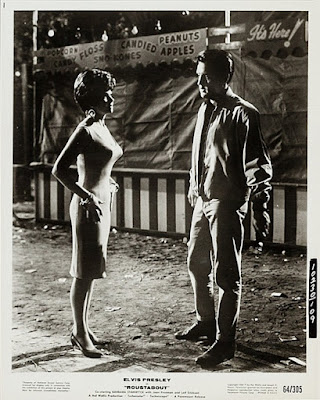

However, despite her limited opportunities, the movie just crackles whenever Barbara Stanwyck and Presley share any screen time as Maggie kinda sees through all of Rogers’ bullshit. According to several trade papers, the part was originally offered to Mae West, who refused to sign on when Wallis wouldn’t make her character one of Presley’s love interests. Stanwyck’s Maggie takes an instant liking to Rogers, but it's more motherly. She sees something in him that no one else can, apparently.

Presley always seemed to fare better on screen when he was paired-up with a veteran actor of this caliber, more focused, and he would also star with Stanwyck’s fellow grande dames of the silver screen Glenda Farrell in Kissin’ Cousins and Joan Blondell in Stay Away, Joe (1968). And after a long and storied career, Roustabout would be Stanwyck’s final feature film as she shifted gears and moved to television, starting with the highly-successful, gender-swapped take on Bonanza, The Big Valley.

To make all of this work on screen as quickly as possible, Wallis turned to John Rich. Rich had been a prolific director for the small screen before Wallis signed him up to direct Wives and Lovers (1962) for the big screen (-- name any TV show pre-1980 and odds are good Rich directed at least three episodes, most notably for Gunsmoke, The Dick Van Dyke Show, and All in the Family, earning himself three Emmy Awards and countless nominations).

Stanwyck, Presley, Rich.

Roustabout would be Rich's second feature film. “I didn’t know much about the musical theater,” Rich later confessed to Gurlanick. “I knew nothing about Elvis. I said, Why me? I had visions of doing rather grandiose pictures but I was going to do the very best I could and try to catch up as quickly as possible.” But despite his best efforts, things got off to a very rocky start.

Unlike Norman Taurog -- G.I. Blues, Blue Hawaii, Girls! Girls! Girls!, Rich had little patience for Presley’s rowdy entourage, their constant distractions and practical joking, which was eating up precious shooting time; and there were rumblings about getting them all banned from the set. “I’m not one for fraternizing too much with the group that are around the players,” said Rich. “But they were around quite a bit and you couldn’t ignore them.” Here, Presley personally intervened, saying, “When these damn movies cease to be fun, I’ll stop doing them. And if my guys go, (expletive deleted) it, so do I.” Things got even more testy on the third day of shooting when Presley insisted he do his own stunts for the fight scene at the roadhouse.

Feeling he was on thin ice already, Rich, against his better judgement, caved and let Presley have his way when he promised to take full responsibility if anything happened. Well, something did happen as the stunt went awry and the actor got clipped in the head just above his right eye to the tune of five stitches. Seeing his career going down the toilet for allowing this to happen, fearing the production would have to be shut down, Rich quickly hit upon the notion to incorporate the wound into the story, making it a result of being run off the road. His apologetic star was very grateful for the save, and after slapping on a bandage the production ran smoothly from there.

For authenticity, the production hired Craft’s 20 Big Shows, a large west-coast based carnival operation that wintered in North Hollywood. For the outdoor scenes, the show was erected in the Potrero Valley, near Thousand Oaks, California. For the interior shots, it was all uprooted and moved into three connecting sound stages on the Paramount lot.

And to Rich’s credit, he exploited this carnival setting perfectly and Roustabout is one of the better looking Presley pictures of this period. Credit should also go to his cinematographer, Lucien Ballard, who shot most of Sam Peckinpah’s films -- Ride the High Country (1961), The Wild Bunch (1969), and The Getaway (1972).

Together, Rich and Ballard eschewed the normal traveling-matte abuse that plagued most of Presley’s pictures and kept it as all-natural as possible. From the opening song, Presley is actually on the road and on the move, singing in the breeze. There were also a couple of long, uninterrupted tracking shots along the midway that weren't easy and came off without a hitch.

And I loved the point-of-view camera work when Rogers serenades his captive audience of one on the spinning ferris wheel, which helps engage the audience over the script’s massive short-comings. And speaking of shortcomings…

As for the music, well, I think the Roustabout soundtrack might be the worst collection of songs ever assembled for a Presley picture. And that is really saying something. Obviously, to keep costs down even more, Parker and Wallis weren’t exactly hiring top-notch songwriters for these pictures. Though it should be noted the best song of the bunch -- “Big Love, Big Heartache” -- was penned by Ed Wood’s ex-girlfriend, Dolores Fuller, who was his co-star in Glen or Glenda (1953).

But the quality didn’t seem to matter because these soundtrack albums still sold and, by some miracle, Roustabout hit the top of Billboard’s Album Chart, knocking The Beatles off the top of the heap -- for one solitary week. It would be Presley’s last No. 1 album until the release of Aloha from Hawaii in 1973.

Roustabout was released to theaters in November of 1964 to not-so-stellar reviews but it still grossed nearly $3.3 million in ticket sales, satisfying both Wallis and Parker. But by contrast, The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night (1964) came out three months prior and was an absolute smash both critically -- it was “the Citizen Kane (1941) of jukebox movies” according to the The Village Voice, and financially, as it raked in a staggering $11-million dollars at the box office. And on top of that, the soundtrack sold over four million copies. Roustabout, meanwhile, tapped-out at 500,000. Both Parker and Wallis were well aware of this development but did little to nothing to meet or match this challenge posed by these British Invaders. In fact, they were kinda busy putting out a massive fire in their own camp that threatened to derail their cash-train permanently.

It was on the last day of principal photography for Roustabout when a certain story broke in the Las Vegas Desert News and Telegram, whose headline read “Elvis Helped in Success of Burton-O’Toole Movie.” The movie was Becket (1964) and, according to the article written by Vernon Scott for the UPI, which meant it appeared in papers all over the country, the more prestigious film wouldn’t have happened if not for “Sir Swivel Hips.”

See, Wallis was interviewed for this article, who admitted that without the revenue generated by Presley, there might

not have been enough “wherewithal” to film Becket, saying, “In order to

do the artistic pictures, it is necessary to make the commercially

successful Presley pictures. But that doesn’t mean a Presley picture

can’t have quality, too.” The article then concludes by saying

Roustabout, currently filming at the time of publication, might not be the greatest,

but then Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton couldn’t sing like Elvis

either.

From the April 24, 1964, edition of The Desert Sun, Palm Springs, CA.

Well, the shit kinda hit the fan after that. Feeling he was being played for a rube, and a direct hit on his insecurities, Presley didn’t appreciate being thrown under the bus like that by his producer. (For the record, Wallis did the same disservice to his Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis pictures, too, in the same interview.) Or how Wallis was earning himself Academy Awards on the back of his box-office earnings, little of which actually trickled down to his own picture’s meager budget coffers. Thus and so, stuck between Wallis and Parker, if there were any doubts left about his acting career being taken seriously, they were gone now. And while he was contractually obligated to perform for Parker in future pictures, you can tell Presley had kind of checked-out from this moment on, acting wise -- especially on the Wallis pictures.

I guess one could take some grim satisfaction on how Parker’s machinations, hubris, and staunch refusal to try anything different, or how his cost-cutting demands for cheap turnarounds and backdoor profiteering, which kept resulting in lower and lower box-office returns, which then begat cheaper and even more dire films, meaning even less profits, led to his own undoing -- it's just too bad he had to take Presley with him. And as his star lost his luster on the big screen, his outlandish salary demands were soon met with indifference.

But Parker did finally get that million dollar payday. For one picture, Tickle Me (1965). But it was all downhill from there. Wallis would officially bow out of Parker’s circus after Easy Come, Easy Go (1967), and Presley’s Hollywood experiment officially came to and end with Change of Habit (1969).

And so, basically, when filming began on Roustabout, Presley’s film career was precariously teetering over a precipice. And by the time it had wrapped, it was officially over, nudged into a near fatal plunge by both Wallis and Parker. Sure, there was still plenty of entertainment to be squeezed out of what came after, when taken as the goofs they were intended to be, but things would never be the same in the Presley camp. His film career, for all intents and purposes, was dead, but nobody bothered to tell the Colonel, who failed to see that his much vaunted carnie sawdust had turned to ash.

Originally posted on April 26, 2008, at Micro-Brewed Reviews.

Roustabout (1964) Hal Wallis Productions :: Paramount Pictures / EP: Joseph H. Hazen / P: Hal Wallis / AP: Paul Nathan / D: John Rich / W: Anthony Lawrence, Allan Weiss / C: Lucien Ballard / E: Warren Low / M: Joseph J. Lilley / S: Elvis Presley, Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Freeman, Leif Erickson, Pat Butrum, Joan Staley, Sue Ane Langdon, Norm Grabowski, Racquel Welch, Billy Barty, Richard Kiel