Our film opens in sagebrush country, with a dusty drifter sacked-out on a make-shift travois being dragged around by a rudderless horse. When said horse finally comes to a halt in front of a trading post, the filthy, lethargic passenger gets off and heads inside, a cloud of detritus in his wake, where he takes a seat and orders a huge plate of beans.

As he gorges himself, this live-action Pig-Pen soon draws the attention of two other customers, who turn out to be bounty hunters as they check the man's face against their wanted posters.

But they quickly lose interest when he doesn’t match up and return to their prisoner -- a wounded little Mexican, wanted for murder, who swears his offense was a crime of passion and self-defense after catching a gringo messing around with his wife.

Here, after finishing up his beans, as he prepares to leave, the stranger smiles and motions for the prisoner to come with him. Naturally, those bounty hunters don’t take too kindly to this and would like to know the man’s name so they can etch it on his tombstone.

But when told his name is Trinity, the two men suddenly cower back -- as Trinity’s nefarious reputation as “the Right Hand of the Devil” apparently precedes him.

Gathering up the Mexican, Trinity (Hill) turns to leave. But on his way out, without even turning around or looking back, the man draws his pistol and blindly fires back into the cabin behind him without ever breaking his stride -- killing both bounty hunters with deadly, preternatural accuracy, who were maneuvering to gun him down from behind. Yeah, I’m guessing that reputation was pretty well earned. (And it all happened so fast, I was clearly unable to get a decent video-capture of the entire sequence.)

Placing the liberated prisoner on the litter, Trinity mounts up and heads to the nearest town, where three armed men block the main street. Seems they’re confronting the town sheriff, demanding the release of their buddy from the cells. And when the rather disinterested sheriff, sitting outside the jail, his nose buried in a newspaper, grunts a refusal, they call him out to settle this dispute with lead.

Challenge answered, the sheriff finally lowers the paper and stands up. Recognizing the burly and bearded brute, Trinity smiles, spurs his horse on, and trots right in between these two disputing factions. And as he slowly plods by, the sheriff recognizes Trinity, too, but doesn’t appear all that happy to see him before turning his attention back to the armed hooligans.

Once clear, Trinity bets the Mexican (Cimarosa) that all three gunmen will be dead before they can even draw. And this proves prophetic as the sheriff quickly guns them all down before the viewer can even blink. When the Mexican asks the sheriff’s name, Trinity says it's his brother, Bambino (Spencer) -- “the Left Hand of the Devil.” And when the two Hands of the Devil meet, rest assured chaos will soon follow as all kinds of hell is predestined to break loose -- just not in the way you’d might think…

When most people think of Spaghetti Westerns, images of Clint Eastwood, adorned in his poncho, chomping on a cigarillo, squinting in the sun, probably filter into your mind's eye. And while Ennio Morricone's wailing soundtrack reaches a fevered pitch, he'd take aim at a sweaty Eli Wallach as the camera zeroed in on his target’s panicked eyes, and then their pistolas would sound-off like a goddamned howitzer as the lead flew and deeds got dirtily done.

That's cool. These are strong, indelible images that only add to the surreal, almost mythical quality of the genre. Of course, Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy -- A Fistful of Dollars (alias Per un pugno di dollari,1964), For a Few Dollars More (alias Per qualche dollaro in più, 1965), and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (alias Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, 1966), both earned that reputation and deserved all kinds of recognition; and would you believe all three hit the States in 1967, all three within one calendar year, turning Eastwood into a bona fide box-office star and made these Euro-Westerns a going concern.

In fact, I’m hard pressed to think of any piece of cinema -- from any genre -- that can stand up to the sheer cinematic fusion of the last 20-minutes-or-so of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. From Tuco’s “Ecstasy of Gold”-fueled search of the graveyard, to the three-way climactic duel, through the final denouement, the direction, the cinematography, the setting, the acting, the editing, and Morricone’s music, are hard to top. And get outta here with that Once Upon a Time in the West (alias C'era una volta il West, 1968) is a superior film crap. Great film, but better? Hell no! And I will gladly die on this cinematic boot hill.

Anyhoo, and perhaps most importantly of all, this infusion of violence and moral ambiguity once more made the Western a viable commodity at the domestic box-office, which had kind of abandoned movie theaters as the 1950s came to a close but found a safe refuge on TV, where it had been thriving.

According to legend, the term “Spaghetti Western” can be traced back to Spanish journalist Alfonso Sancha. And while some find this nomer derogatory and prefer the term, western all'italiana, the prior designation stuck like, heh, well-done pasta to a wall. Also, it's a bit of a misnomer when you consider that while the majority of them were produced by Italian studios, they were financed by German money (or British money, or American money), shot in Spain, with an international cast, making them, as filmmaker Brian Trenchard-Smith put it, more of a Euro-Pudding. And on top of all that, the true origin of the genre itself is hard to pin down.

Ironically enough, one of the first Italian westerns ever made was La Vampira Indiana (1913), a silent mash-up of the wild west and vampire folklore, which was directed by Vincenzo Leone, Sergio’s father, and starred his mother, Bice Waleran. But what would come to be recognized as the Spaghetti Western didn’t really take root until Raoul Walsh’s The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw (1958) and Michael Carreras’ Savage Guns (1961), which were both co-financed with Spanish money and shot in Spain, which served as a surrogate for the deserts of the American southwest, setting the template for what would follow.

Things solidified even further when American producer Albert Band helmed the Italian and Spanish co-production of Gunfight at Red Sands (alias Duello nel Texas, 1963), starring Richard Harrison, which also featured the first Spaghetti Western soundtrack composed by Morricone. Band then followed that up with Grand Canyon Massacre (alias Massacro al Grande Canyon, 1964), where the burgeoning genre really started to stretch its legs and started thinking outside the usual trappings thanks to its director, Stanley Corbett -- a pseudonym of Sergio Corbucci. Bruno Bozzetto, meanwhile, claimed it was he who invented the genre with his animated spoof, West and Soda (1965), which was in production well before the cameras rolled on A Fistful of Dollars but was released after it premiered.

However, I don’t think anyone would deny that it was Leone who would define the genre with his trilogy -- plus Once Upon a Time in the West and A Fistful of Dynamite (alias Giù la testa, alias Duck, You Sucker, 1971), which would be expanded upon further and rivaled by the likes of Corbucci -- Django (1966), Navajo Joe (1966), The Great Silence (alias Il grande silenzio, 1968), Enzo Castellari -- Kill Them All and Come Back Alone (alias Ammazzali tutti e torna solo, 1968), Keoma (1976), and dozens of others as Leone’s box-office success bred dozens of imitators who all tried to cash-in.

Yup. After 1967 some 300 Spaghetti Westerns flooded the market, which just as quickly drowned due to this oversaturation, and then threatened to dry-up altogether by the end of the decade. And so, by 1970, to remain viable it was time to start thinking even further outside the box, which is where Enzo Barboni stepped in and stepped-up, with a funny idea that had been percolating in his head for quite a while.

Barboni’s first experience as a filmmaker and camera operator happened while working as a combat correspondent during World War II for his native Italy. After hostilities ceased, he then began working as an assistant cameraman on the likes of William Wyler’s Roman Holiday (1953) and Mario Bonnard’s The Last Days of Pompeii (alias Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei, 1959).

Enzo Barboni

By the 1960s, he had been promoted to cinematographer and started a long and fruitful working relationship with Corbucci, starting with a couple of historical epics/peplum Duel of the Titans (alias Romolo e Remo, 1961), with former Hercules Steve Reeves and former Tarzan Gordon Scott as Romulus and Remus, and The Slave (alias Il figlio di Spartacus, 1962), where Reeves played the son of Spartacus in an unofficial sorta kinda sequel to Spartacus (1960). Barboni would also lens the majority of Corbucci’s westerns, too, including Grand Canyon Massacre, Django -- which, for my money, is the second best Spaghetti Western ever made, and The Hellbenders (alias I crudeli, 1967).

Barboni was also a favorite of Mario Caiano, who used him for other genre fare like Erik, the Viking (alias Erik il vichingo, 1965), Nightmare Castle (alias Amanti d'oltretomba, 1965) -- a gothic tale of preternatural revenge starring the great Barbara Steele, and A Train for Durango (alias Un treno per Durango, 1968). He also shot Texas, Adios (alias Texas, addio, 1966) and Django, Prepare a Coffin (alias Preparati la bara!, 1968) for Ferdinando Baldi, where Barboni also first worked with actor Terence Hill, who was cast because he bore a strong resemblance to Franco Nero, who played Django in the original; and Nero was cast in that because he looked like Eastwood, but skipped out on the sequel to play Sir Lancelot in the big screen adaptation of Camelot (1967), which brings us back to Hill.

And it was while shooting The Five-Man Army (alias Un esercito di 5 uomini, 1969) for Italo Zingarelli and Don Taylor, which co-starred Bud Spencer, when Barboni, with Zingarelli’s encouragement, started putting his notions into a script for a western called Trinità -- Trinity; ideas that had been kicking around since shooting Django back in 1966, which Corbucci had blended elements of Gothic horror into.

As to what those notions were, well, seeing the comedic potential that could be wrung out of these hyper-violent and highly stylized Oaters, Barboni went in the opposite direction, feeling a parody was in order, and infused his script with humor and slapstick. Meantime, he slid into the director’s chair for The Unholy Four (alias Ciakmull, L'uomo della vendetta, 1970), where an asylum is burned down as part of a bank heist and four escaped inmates go on the lam. And while not terrible by any definition, the film did poorly at the box office as things continued to fizzle. Luckily for Barboni, he finally got a nibble on that Trinity script from executive producer Roberto Palaggi as a follow-up.

Now, what would eventually be released as They Call Me Trinity (alias Lo chiamavano Trinità, 1970) was originally set to star two holdovers from The Unholy Four: Peter Martell as Trinity and George Eastman as Bambino. Martell had starred in a ton of Spaghetti Westerns ranging from Michele Lupo’s Arizona Colt (1966) to Baldi’s The Forgotten Pistolero (alias Il pistolero dell'Ave Maria, 1969).

Eastman, meanwhile, was no stranger to the western either, starring in a ton of Django knock-offs -- Django Shoots First (alias Django spara per primo, 1966), Django Kills Softly (alias Bill il taciturno, 1967), Django, Prepare a Coffin, but the six and a half foot tall actor is probably better remembered for his horror roles, especially with the likes of the grisly The Grim Reaper (alias Antropophagus, 1980) and the ghastly Absurd (alias Rosso sangue, 1981) on his resume; both of which he wrote and starred in for Joe D'Amato, and both of which score pretty high on the vomit-meter.

But as fate would have it, after starring together in a trio of films for Giuseppe Colizzi -- God Forgives... I Don't! (alias Dio perdona... Io no!, 1967), Ace High (alias I quattro dell'Ave Maria, 1968) and Boot Hill (alias La collina degli stivali, 1969), Terrence Hill and Bud Spencer had good box-office buzz together; and as those three films progressed some of that comedy Barboni was so keen on had already started to show up and seep through with the way those two played off of each other.

And so, at Zingarelli’s suggestion, who would also serve as a producer on the film, Martell and Eastmen were out and Hill and Spencer were in for this spoof ‘n’ goof on the already amped-up conventions of the genre.

Here, Barboni -- under the name E.B. Clucher, just took it to the next logical step and let the cameras roll, resulting in, sure enough, a trinity -- a three-punch combo of a Spaghetti Western, a Three Stooges short, and a vintage Warner Bros. cartoon as Hill and Spencer reunited as Trinity and Bambino. And while they played brothers, there was no familial love lost between their characters as they retire to the jailhouse, leaving the three dead tinhorns to the undertaker, where they dig the offending bullet out of the Mexican, stuff a full pardon into his pocket, and then toss him into a cell so he can sleep off the “anesthetic” -- about a fifth's worth.

Then, Trinity starts poking the bear a little, curious as to how in the hell did his brother, who, at last check, was a notorious horse thief serving a stretch at the State Penitentiary in Yuma, become a town sheriff? Well, after he broke out of prison, Bambino came upon a man traveling through the desert. Seems this man was to be the new sheriff of -- wherever the hell we are. And then, after shooting this stranger in the leg, Bambino stole his horse, stole his badge and identity, and took his place when the town welcomed him with open arms.

However,

the older brother makes it clear he’s only biding his time under this

perfect cover until his partners -- Timmy and Weasel, finally catch-up

to pull off a heist of the equine variety that he’s concocted.

Meanwhile, Trinity wasn’t the only witness to that earlier gunfight; and when a Major Harrison (Granger) gets debriefed on what went down, he’s rather disappointed the new sheriff survived this showdown -- that he most likely orchestrated. See, Harrison and Bambino have been butting heads ever since he arrived. In particular over a group of sodbusters the Major has been trying to run off so he can expand his ranching operation onto their prime grazing land.

But! Bambino doesn’t really care about the farmers; he just wants to get his hands on the Major’s prized horses before they get moved into a protected valley, which is currently occupied by those farmers -- that aforementioned scheme he was talking about.

When Trinity asks why the farmers don't just fight back, he's told they can’t because it’s against their religious principles; for these pilgrims abhor violence and won’t allow themselves to bear arms. And since things are starting to get a little hairy, and needing some help to keep the peace and thwart Harrison, with his partners terminally overdue, here, Bambino manages to convince a reluctant Trinity to be sworn in as his new deputy.

But he barely has his badge pinned on before, in rapid succession, Trinity falls in love with a couple of those farmer’s daughters, Sarah and Judith (Hahn, Pedemonte), then beats up a few of Harrison’s goons in retaliation for not letting these fair maidens use the general store, and then confronts the Major personally; in the process of which he injures two more of his men while encouraging them all to get out of town.

“One shop destroyed; three heads split like overripe melons; one man wounded, and one castrated. All in two hours. Just two hours I left you alone,” bellows Bambino as he takes in the aftermath of his brother’s busy afternoon while he was out scheming. “Two hours?!”

And while told to tone it down or he’ll blow the whole thing, that night, after Bambino has gone to bed, Trinity tries to pick yet another fight with Harrison’s men after they say something bad about his mother. Seeing all of this, and thinking he will need some help, Old Jonathan (Zacharias) -- think Walter Brennan, or Jack Elam, or some other crotchety old coot sidekick -- rousts Bambino, who joins his little brother at the saloon and is told what they said about their mom.

Thus, even though what they said about their dear old mom being a dirty old whore was true, the family honor must be upheld. Thus and so, the two brothers start throwing haymakers and quickly wipe the floor with Harrison’s goon squad -- well, Trinity mostly watches while Bambino does all the hard work.

Now, this would be a recurring theme not only in this film but in nearly all of Hill and Spencer’s comedies, as Hill’s character usually started these brawls but it was Spencer who always finished them with his patented skull-thump. And for the record, Trinity and Bambino’s mother was a notorious New Orleans cathouse madame -- that’s canon. (We even meet her in the sequel.) Thus, her sons weren’t even objecting to the references of her being “dirty” or being a “whore” but the fact of her being “old" but not THAT old.

Come the dawn, in an effort to keep Trinity away from Harrison, the brothers ride out to the farmer’s camp, where Brother Tobias (Sturkie) invites them to stay for dinner. And as they gather around the table, Sarah and Judith make sure their guests have the proper headgear on before they give thanks. But then their meal is suddenly interrupted by the noisy arrival of a gang of mounted Mexican banditos.

Led by the degenerate Mezcal (Capitiani), who, apparently, has raided this camp before and is well aware of their oath of non-violence; which, in turn, explains why he takes great pleasure in lining up the menfolk to slap them around for a while because they can’t defend themselves.

Not realizing there are a couple of atheists hidden in the deck this round, after knocking down the first two men with ease, the next in line is Bambino, who gets smacked twice with no effect. Here, Mezcal winds up for a third blow only to get his brain scrambled by one of those skull thumps, which drops him like a sack of rocks. Concussed into a babbling stupor, the other bandits quickly gather up their jefé and vamoos.

Meanwhile, back in town, Harrison has hired a couple of professional gunslingers to take care of his “law and order” problem. But when his hired mercenaries follow Trinity into a store, their target demands to see their underwear. We then immediately cut to the street, where we hear gunfire and general carnage coming from inside the building, followed by the two gunmen, who come flying out of the store, sans pants, who flee town as fast as their feet will carry them, never to be heard from again.

After this embarrassing incident, Harrison confronts Bambino directly, demanding his deputy’s immediate resignation or he will be forced to contact his friend, the Governor, and get a new sheriff appointed. With that, unable to control his brother, who is poised to ruin all of his plans -- like he always does, Bambino fires Trinity and then escorts him out of town at gunpoint.

Circling back to the farmer’s camp, Trinity finds Sarah and Judith bathing in a creek and joins them -- horse and all. Torn between these two, he’s then informed they’re a colony of Mormons, meaning both can be his wife. Loving this idea, Trinity decides to become a Mormon farmer on the spot. However, they still must deal with Harrison. And since trying to convince Tobias that they need to defend themselves will go nowhere, Trinity realizes he’ll need some outside help just as two familiar riders approach the camp.

Recognizing Timmy and Weasel (Ross, Marano) as the two parched outlaws partake of the watering trough, they’re told Bambino’s been waiting for them. Seems they were delayed by a gimpy sheriff who was looking for a man that stole his badge -- and when I say “delayed” I mean they shot him in his good leg, stole his horse, and broke his crutches. Here, Trinity risks heading back into town so they can meet the man who stole that badge, where he’ll make his pitch to help the farmers and take care of Harrison once and for all.

But Bambino adamantly refuses -- until Trinity offers that if his brother will help him out here, he promises to get married and settle down, which means the possibility of them ever crossing paths again in the future would be unlikely, which would mean Trinity would stop messing up his plans, and, well, Is it any wonder why Bambino has a sudden change of heart?

Meantime, Harrison and Mezcal have formed an alliance, which hinges on the bandit driving the farmers out of the valley for twenty of the Major's best horses; but Mezcal only agrees if Harrison will allow him to steal them. Receiving the horses would be undignified and an insult to his family's reputation, after all. And when these terms are accepted, Mezcal sends a man to spy on the farmers. Back at the Mormon's camp, since they won’t use guns and will only fight in the case of self-defense, Trinity, Bambino, and the others do their best to give these farmers a crash-course on how to fight without fighting -- stress on the “crash.” Thus, judging by their technique, these farmers'll probably cause as much -- if not more, damage to themselves as the banditos ever could.

Then, when he spots Mezcal’s spy, Bambino sends Weasel out to bring him in alive. Upon questioning the prisoner, they discover Harrison’s plan and decide to spoil it by beating them to the punch. And so, disguising themselves as Mezcal’s men, the group manages to steal all of Harrison’s horses for themselves. This, in turn, brings Harrison, Mezcal, and all of their men to the Mormon camp. Luckily, Bambino planned ahead for this very contingency, which quickly falls apart after they manage to get everyone to discard their guns.

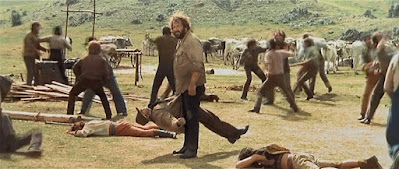

And so, it's down to fisticuffs, with our quartet comically outnumbered. However, as he implores for a peaceful resolution, Brother Tobias starts reading from the Scripture, specifically the Psalms, verse 144. You know, the one that goes, “Praise be to the Lord my Rock, who trains my hands for war, my fingers for battle. He is my loving God and my fortress, my stronghold and my deliverer, my shield, in whom I take refuge, who subdues peoples under me.” Yeah, that one.

With that, and with the Almighty's permission, an all-out brawl explodes as the Mormons join the fracas. This fight then goes on for a good ten minutes, as Mezcal keeps breaking larger and larger pieces of furniture on Bambino with no effect at all; and while the farmers didn’t quite get all those fighting moves down, they do manage to get the job done. Even Trinity pitches in for the entire fight until the good guys win the day and Harrison is banished to the hinterlands of Nebraska and ... HEY! Yeah, I know. We’re the OTHER Dakota. *sheesh*

Thus and lo, victorious, Bambino sends Timmy and Weasel to round up the horses they stole so they can head out for California and cash in. But when they herd the animals together, they discover they’ve all been marked with the Mormon’s brand in the interim.

Smelling his weasel of a brother’s hand in this, Bambino moves to break Trinity in half, who only thought it was fair compensation for the farmers after all the damage Harrison and the others had done. Seething for a few moments, Bambino eventually calms down, saying, "I don’t hate you. I hate our Ma for not strangling you when you were born." He then rides off with Timmy and Weasel, leaving his brother far, far behind him.

After they go, Brother Tobias gathers his flock and begins to thank the Lord with prayer. He also welcomes their new Brother Trinity into the fold, and talks about all the hard labor and sweat he’ll have to put in for his new chosen vocation. And with each horrid description of toil and trouble, Trinity looks to his brother, who is getting farther and farther away -- and by the time Tobias finishes the prayer, Trinity is long gone.

Later, when Trinity finally catches up with them, Bambino warns that if he’s going west, Trinity had best go east -- or else. Left behind again, as he prepares to take his customary spot on his mobile bed, a wagon approaches -- driven by a man with a very visible set of crutches.

When the real sheriff asks if he’s seen the three men on his wanted posters, Trinity bears false witness and claims these familiar hooligans just robbed him and points off in the direction Bambino and the others just went. After the sheriff takes off in pursuit, Trinity stretches out on his litter, tells his horse to head for California, and they slowly ride off after them and into the sunset.

Apparently it was Zingarelli who suggested Barboni split his main character Trinity into two bickering and brawling brothers in the early stages of the script. And with that fateful decision, Barboni managed to catch lighting in a bottle as They Call Me Trinity would go on to set all kinds of box-office records in Italy, and soon drew the attention of Joseph E. Levine and Avco Embassy, who imported it to the States in 1971, where it also struck a chord with audiences, myself included.

See, when I was around four years old back in the 1970s, my family partook of a drive-in double feature of They Call Me Trinity and its sequel, Trinity is Still My Name (alias Continuavano a chiamarlo Trinità, 1971).

And it was a true hit for me and my siblings, and we would spend hours in the backyard playing “Trinity.” My oldest brother got to be Bambino, my other older brother got to be Trinity, while I … I got the living crap beat out of me on a routine basis by a series of kicks, jabs, and imitation skull thumps. All in good fun, but I swear I still have a few lumps on the top of my cranium, which only added to the film's lasting impression.

And we weren’t the only ones as the film proved a hit all over the world -- England, Spain, and especially in Germany. No one involved in the production really expected this kind of break-out hit, meaning not only was an immediate sequel in order but Spencer and Hill would continue to team-up in a series of comedies -- and not just westerns, with Blackie the Pirate (alias Il corsaro nero, 1971), All the Way, Boys! (alias ...Più forte ragazzi!, 1972), Watch Out, We’re Mad! (alias ...altrimenti ci arrabbiamo!, 1974), which is one of my faves, Crime Busters (alias I due superpiedi quasi piatti, 1977), Odds and Evens (alias Pari e dispari, 1978), I’m for the Hippopotamus (alias Lo sto con gli ippopotami, 1979), Double Trouble (alias Non c'è due senza quattro, 1984) and Miami Supercops (1985).

And with all respect to Barboni, it was Hill and Spencer, and their chemistry, that made all of this nonsense work. Imagine a pairing of Bugs Bunny and Bluto from Popeye, only they’re on the same side fighting a pack of Wile E. Coyotes.

Hill is charming and quick on his feet, stirring up trouble or romancing the women. And Spencer could do more with a grunt than most actors I know giving a soliloquy, and was a true master of the slow-burn -- the only ones I can think of who did it any better were Oliver Hardy and, maybe, Ted Knight.

I love the scene where old Jonathan wakes up Bambino to say his brother started another fight with Harrison’s men at the saloon, and how Spencer then visibly perks up for a second -- and actually smiles in anticipation as he asks, hopefully, “Did they kill em?” only to be severely disappointed when the answer is “No.” Or how whenever the townsfolk would offer a friendly, "Hello,” to the new sheriff only to be rebuffed with a quick, "Shuddap!" And that moment during the climax, where Trinity accidentally punches Bambino during all the ruckus is pure comedy gold.

Again, these two guys had a gift for physical comedy, and Hill and Spencer did all their own stunts, too. The action set-pieces and epic brawls were choreographed by Giorgio Ubaldi, and the vast majority of the supporting cast were played by stuntmen, including Riccardo Pizzuti, Harrison’s chief goon, who would go on to appear in a lot of those Hill-Spencer vehicles; and who would also be on the receiving end of a lot of those skull-thumps, which were a thing of beauty. I don’t know if those were Ubaldi’s idea or Spencer’s, but the sheer joy of watching Bambino smash his meaty fist on top of someone’s head, dropping them on the spot, never fails to crack me up.

Credit also to Roger Browne and Richard McNamara, who did the dubbing for Hill and Spencer respectively in the English release. See, to save money, the majority of Italian films were shot without sound and all the dialogue and SFX were over-dubbed in later. And Brown and McNamara really helped bring those characters to life, enriching them greatly with their inflections and delivery. So much so, when they’re absent in some of the later films it’s kind of off-putting -- it just doesn’t sound right; and, if I’m being honest, makes them not nearly as good.

What’s really good, however, is Franco Micalizzi’s score. Love the main theme, “Trinity: titoli” which starts with a rattlesnake rattling, then strings, and then Alessandro Alessandroni kicks in with the whistling chorus before Annibale Giannarelli’s vocals take over. Quentin Tarantino was a huge fan as well, as the music appeared in both the trailer and the end titles for Django Unchained (2012).

Let's give some credit to Barboni, too, as his script has some genuinely funny moments. I love the scene where Harrison gives his speech about the “noble horse” to his newly hired guns -- a delightfully effete performance by Farley Granger, and how his regulars roll their eyes, having heard this speech one too many times already. Or how after the final brawl ends, and the Mormons quickly start helping all the banditos whose heads they had just kicked in.

And just like with Leone, the box-office success of They Call Me Trinity brought on a rash of imitators, including Roy Colt and Winchester Jack (1970); but none could hold a candle to the original. Granted, the comedy on display here is definitely not highbrow nor sophisticated, and rather blunt -- though clever in its own way. Yeah, Barboni definitely owed more to the Three Stooges than Leone. And like with the Stooges, you either love ‘em or you don’t -- if that helps you gauge the temperature here. Now, about that sequel…

Originally posted on February 15, 2001, at 3B Theater.

They Call Me Trinity / Lo chiamavano Trinità… (1970) West Film :: AVCO Embassy Pictures / EP: Roberto Palaggi / P: Italo Zingarelli, Joseph E. Levine, Donald Taylor / D: Enzo Barboni / W: Enzo Barboni / C: Aldo Giordani / E: Giampiero Giunti / M: Franco Micalizzi / S: Terence Hill, Bud Spencer, Farley Granger, Steffen Zacharias, Dan Sturkie, Gisela Hahn, Elena Pedemonte, Remo Capitani

%201970.jpg)

_07.jpg)

_08.jpg)

%201970.jpg)

%201970.jpg)