"Bass-togg-nee. I won't be forgettin’ this place in a hurry."

We open near Mourmelon, France, where the 101st Airborne Division is currently resting, re-arming and receiving replacements after several weeks of fierce fighting in Holland in service of Operation Market Garden. And after watching a platoon perform some precision drilling, completely in-step with the barking commands of First Sergeant Kinnie (Whitmore), two of those replacements, Jim Layton (Thompson) and his buddy, Bill Hooper (Beckett), soon part ways to join their respective squads but promise to stay in touch.

Anxious to sew on his new Screaming Eagle patch and meet his new squad-mates, despite his clumsy efforts to ingratiate himself, the wary veterans basically ignore young Layton; and the harder he tries to fit in, the worse the results as he works his way around the tent, meeting the rest of the men as he's kicked out of successive bunks that he didn't know were already occupied.

The squad does perk-up a bit when Holley (Johnson) returns; a familiar face, who was recovering in Paris from wounds received while fighting in Holland. Seems the whole company, except for the replacements, have all been granted three-day passes to Paris starting the next day -- and the jovial Holley is given all kinds of grief for returning just in time to go back on leave.

And

while anticipation is running high as Holley regales them of the

wonders to be found in the *ahem* ‘not so well lit corners’ of the City

of Lights, when “Li'l Abner” Spudler (Courtland) asks to buddy-up with

Jarvess (Hodiak) and raise a little hell his pal declines, saying he

plans to find "a private room with a private bath" -- even if he has to

take one by force, for some much needed solitude.

Squad Sgt. Walowicz (Cowling) will be skipping the Paris trip altogether so he can compete in a regimental football game, even though Corporal Staniferd (Taylor) constantly gives him grief over this, saying, “He’d rather play football than eat.” Meanwhile, Layton keeps on moving and clumsily knocks over a baby’s picture belonging to Hanson (Anderson), who mistakes it for a little girl when it's really a boy, meaning it's time to move on yet again.

However, the good news continues for the rest of the squad as old Pop Stazak (Murphy) announces he's just been granted a dependency discharge to take care of his sick wife. And as Kipp (Fowley), the squad malcontent, wonders aloud over who will take care of Johnny Rodrigues (Montalban) after his mentor leaves, Rodrigues responds by threatening to kick in Kipp's false "GI teeth" -- which leaves only Bettis (Jaeckel), who's convinced every Wehrmacht bullet has his name on it, who wishes he could go home, too, before one of them inevitably finds him.

With that, things finally wind down, they all hit the sack and kill the lights, leaving a flummoxed Layton standing in the middle of the tent, in the dark, with no place to go. And while the men of the Second Squad of the Third Platoon of the 101st Airborne’s I-Company drift off to sleep, dreaming of a wild time in Paris, they will soon wake-up to a nightmare…

As the winter of 1944 settled over the European Theater of Operations during World War II, after Market Garden proved a bridge too far and "fell on it's ass," and the Battle of the Hurtgen Forest accomplished little except massive casualties on both sides, the Allied and German lines pretty much stabilized along the Siegfried Line. The war wasn't going to be over by Christmas like everyone had hoped, and it appeared that the opposing armies were content to just dig in and wait out the winter before launching any new offensives in the spring of '45. Or so the Allies thought.

The Germans, meanwhile, had secretly amassed men, tanks, and material on the outskirts of the Ardennes along the Schnee Eifel for a planned surprise attack. History would prove this to be their last major offensive action of the war, which would come to be known as the Battle of the Bulge. History would also show they lost this gamble, but during the operation's initial stages, the final outcome was very much in doubt.

With the element of total surprise, the Germans launched their final blitzkrieg on December 16, hoping to drive a wedge between the American and British sectors. The main objective was to push their panzers all the way to Antwerp in hopes of forcing a negotiated peace with the western Allies, so they could then concentrate fully on the Soviet juggernaut currently steamrolling them on the eastern front.

And with the Allies caught with their pants down, this counter-offensive initially met with great success. But soon enough, those metaphorical pants were pulled back up and the German advance was soon stymied on all fronts by pockets of slapped together but stubborn resistance, buying General Eisenhower enough time to recover, reinforce with his idle airborne divisions -- the 82nd and the 101st, and then counterattack to eventually thwart Hitler's last gamble.

Admittedly, that is a very over-simplified version of what transpired between 5:30am on December 16, 1944, and January 28, 1945. And there are many harrowing, dastardly, and heroic tales to be told about the Battle of the Bulge -- Patton’s 3rd Army push, the Battle of St. Vith, the defense of Malmedy, and the Malmedy Massacre, but the most storied account was the siege of the Belgian town of Bastogne.

A strategic objective for both sides because seven major highways intersected there, Bastogne was vital and the Allies had to keep it out of German hands. With the Allied Air Corps grounded by bad weather, holding these roads and bridges were a top priority for ground forces to stop the marauding German panzer groups. And to defend Bastogne, Eisenhower chose the 101st Airborne.

Facing one of the harshest winters on record, with almost no food (-- the defenders were sustained on flour flapjacks and snow), medical supplies (-- the entire 101st Medical Staff were captured early during the fighting), and scarce ammunition, the besieged units managed to hold off the German offensive from December 19 until elements of Patton's 4th Armored officially broke the siege on December 27th.

And that's where the film Battleground (1949) technically ends. But it begins (-- after that opening preamble,) with First Sgt. Kinnie rousting his platoon out of their slumber with some bad news. Seems no one's going to Paris because the Germans have made a breakthrough somewhere, so the 101st is moving up to the frontline to plug this new breach. When Jarvess asks where, Kinnie doesn't know; but since it's a secret move, the men will have to remove their division insignia. Thus, as the others scramble into their gear, Layton dejectedly tears off the patch that he had just so proudly sewn on.

A few frantic minutes later, the men are assembled to be loaded up on trucks, destination still unknown. A fretting Pops still hasn't received his official discharge papers so he has to go with them, praying those orders will quickly catch up. On the limited bright side, during the long and bumpy ride to wherever they’re going, the ice begins to break a little as Staniferd offers Layton a cigarette; and even though he doesn't smoke, the young private thanks him profusely.

When the convoy finally arrives in Bastogne, word comes they'll be billeted there for the night. Here, Layton’s platoon lucks out, drawing a house occupied by the lovely Denise (Darcel) as a temporary barracks. Instantly smitten, Holley, armed with several chocolate bars, tries to put the moves on her -- even though she can't speak any English.

Jarvess does his best to translate for him until he bundles up to relieve Layton, who’s on guard duty outside. The cold night has also brought a thick, eerie fog, which suddenly disgorges dozens of ghostly figures, who soon coalesce into a retreating force of American infantry.

Here, Jarvess, the most vocal about not knowing where they are and what they're supposed to do, gets the first inkling of what's really going on as the fleeing, shell-shocked men tell of the German onslaught that's coming right behind them. He also finds out the 101st will soon be the only ones left to hold the line here while everyone else "strategically withdrawals."

The next morning, confusion still reigns as Holley manages to pilfer some eggs before I-Company is ordered out of Bastogne to help form a defensive perimeter before he can eat them. Safeguarding these eggs like gold, Holley marches with the other men out of town, diving for cover when the German artillery shells start falling while trying to keep his shells intact.

Taking up a position in the surrounding trees, the men pair-up and start digging foxholes. Being the odd man out, Layton struggles alone as the other men take turns. And while a paranoid Bettis digs deep, deeper than needed, Holley breaks open the eggs and starts to cook them -- until Walowicz returns with orders to move again, rendering all their efforts useless, bringing curses from his men -- especially Kipp, who grumbles how just once he'd like to dig a foxhole and find out that's the one he'll be sleeping in.

Dumping the liquefied eggs into his helmet, Holley is careful not to spill any as they move to the next position and start digging again. But before he can once more try to cook his breakfast, Holley is ordered to take the first shift guarding a nearby roadblock with Kipp and the new guy (Layton). Leaving the eggs with Bettis, Holley promises him half if he doesn't get any dirt in them. Later, at the checkpoint, as Kipp and Holley pull rank, take shelter, and snooze in the ditch, Layton challenges a passing patrol. Answered with the correct password, as they file by, the lone sentry confirms to a passing Lieutenant that this is the road to Neu Chateau and there’s a bridge ahead.

Here, Holley stirs long enough to comment on how that officer wasn’t very bright, failing to remove his insignia bars in a combat zone, making him a prime target for enemy snipers. However, the enemy is a lot closer than he thinks as further up the road, one of those soldiers trips and curses in German, bringing a swift rebuke from that same Lieutenant to only speak English.

Now, to help explain what exactly goes on here, we need to first step back and talk about screenwriter Robert Pirosh, who broke into the film industry writing comedies for The Marx Brothers -- A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Races (1937), was one of many contributing writers on The Wizard of Oz (1939), as well as writing for Veronica Lake on I Married a Witch (1942).

When the United States officially entered World War II in December, 1941, Pirosh enlisted and wound up serving in the 35th Infantry Division. Rising to the rank of Master Sergeant, he saw action in the Ardennes during the Bulge and Pirosh was part of a push that made its way into Bastogne to help reinforce the 101st during the siege.

Image courtesy of thelastjump.com

And before we go any further, I'd like to clear something up: Though the 101st Airborne deservedly gets the lion's share of credit for the defense of Bastogne -- and this in no way should be construed as any kind of knock against the Screaming Eagles, but, they weren't the only ones there. The 10th Armored, elements of the 609th and 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the 333rd and 969th Field Artillery Battalions, a pair of colored units, all provided much needed support. (There was also Team SNAFU, a group of about 600 stragglers and support staff from other units, who were armed and organized to help with the defenses.) And before the battle was even over, and the outcome far from decided, these surrounded defenders were dubbed "The Battle Battered Bastards of Bastogne" -- a name that is still associated with the 101st Airborne to this day, joining their Pacific brethren, "The Battling Bastards of Bataan.”

After the war ended, Pirosh returned to his former profession, where his time in the service would greatly affect and influence several of his future projects and screenplays; one of which took him back to Bastogne in 1947 for research, where he found his old foxhole outside the town of Harlange. It was still covered in rendered pine branches, and littered with several K-ration boxes. "My mind was always on a possible picture to be written after the war," said Pirosh in a later interview. And that picture would be Battleground, which was based on Pirosh’s experiences fighting in and around Bastogne, and it would serve as a tribute and dedication for those who fought and died there.

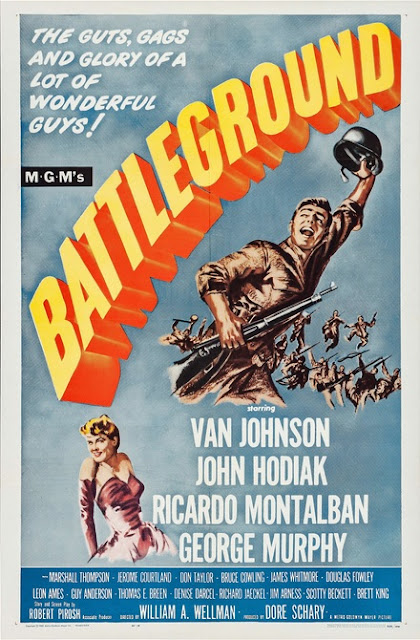

Pirosh then presented his finished script to Dore Schary, who was currently working at RKO under Howard Hughes. Schary was probably best known for producing a string of Cary Grant comedies -- The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer (1947) and Mr. Blandings Builds his Dreamhouse (1948), and several stellar pieces of film noir, including The Spiral Staircase (1946), They Live by Night (1948) and The Set-Up (1949). Schary instantly fell in love with Pirosh's script and began developing it for production. Also of note, not wanting anyone to copy their idea, they hid the production under the false title, Prelude to Love.

They needn’t have bothered as, unfortunately, Hughes wasn't nearly as enthusiastic, convinced there was no longer a market for this type of genre picture since the war was over. And while Schary fought long and hard and spent nearly $100,000 on it already, “Prelude to Love” was cancelled. But! The film wasn’t quite dead yet. See, when Schary left RKO for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1948, he took Pirosh and the Battleground script with him. At the time, MGM, still clinging to its pre-war glory days, had not adapted well for the post-war market. And after a string of high profile flops as the 1940s drew to a close, with money hemorrhaging out, and needing to right the ship, Nicholas Schenk, the head of the board at MGM, sent out feelers to an eager Schary due to his magic touch of providing huge box-office hits on minimal RKO budgets.

And it was this very same proven track record that overcame the same resistance at MGM that there was no audience for this kind of war picture anymore; and frankly, Battleground just wasn’t an “MGM Picture” according to the studio’s chief, Louis B. Mayer. Still, the producer persevered and his personal pet project went into production on what a doubtful industry quickly dubbed “Schary's Folly.”

But then Battleground picked-up some much needed momentum when Schary signed on William Wellman to direct. A veteran of the first World War, “Wild Bill'' Wellman was the clinical definition of a Hollywood maverick. A demanding but well respected and innovative craftsman, both producers and actors wanted to work with the hard-nosed director but were well aware of Wellman’s infamous temper. Known for his own stark and brooding keyhole style in films like The Public Enemy (1931) and The Oxbow Incident (1942), he could also handle action and adventure with the likes of Call of the Wild (1935) and his version of Beau Geste (1939) starring Gary Cooper; Wellman also had a solid touch with screwball comedies, ranging from Nothing Sacred (1937) to Roxie Hart (1942) and the riotous murder mystery, Lady of Burlesque (1943).

Wellman had already made two great war films; the first being Wings (1927), which focused on fighter pilots in World War I that would go on to win the inaugural Academy Award for Best Picture. A veteran combat pilot of the same war, Wellman was producers Lucien Hubbard and Jesse L. Lasky’s first choice for Wings, but he was the second choice for Lester Cowan’s The Story of G.I. Joe (1945).

Based on the book Brave Men by the beloved war correspondent Ernie Pyle, Cowan had wanted John Huston to direct this autobiographical film based on the strengths of Huston’s two combat documentaries, Report from the Aleutians (1943) and The Battle of San Pietro (1945), because they were so “unflinching in [there] realism,” which was exactly what the producer wanted. Like with Pyle’s columns, dispatches, and his collected works -- including his Pulitzer Prize winning piece, The Death of Captain Waskow, which would serve as the film’s narrative’s backbone, The Story of G.I. Joe would be a different kind of war film, focusing less on the abstractions of war and the jingoism of why the fight and focused more on putting a face on those who were doing the actual fighting and the grinding psychological effects combat had on them, bringing some humanity to something so terribly inhumane.

But Huston was still serving in the Army Signal Corps at the time, forcing Cowan to go with Plan B -- only Wellman didn’t want anything to do with the film and stubbornly refused all overtures, telling the producer he had no love for the infantry due to his own experiences with them in World War I and a later butting-of-heads with an obstructing military technical advisor on Wings. But Cowan was persistent, even under the threat of violence; and on the third attempt, with Pyle himself taking over negotiations, Wellman had a complete change of heart and would embrace the prospects of the film wholeheartedly; and through him, according to Lawrence Suid’s Guts and Glory: The Making of the American Military Image in Film, that even though “Wellman was dictatorial in his management of the filming and crucial to the style and final form of the script, [his] greatest impact was as the catalyst for the collective process of bringing together Pyle, his stories, the actors, and the Army to create a uniquely realistic movie."

Wellman would put this same kind of authentic, authoritative stamp on Battleground, too; right down to consulting on the script. And when the cameras rolled, Wellman and cinematographer Paul Vogel weren’t shy and put the camera right into the middle of the action just like he had done in The Story of G.I. Joe; and the fight scenes were so intense and so well staged that audiences found themselves in simulated foxholes, ducking for cover from those same incoming bullets, mortar shells, and grenades as our featured players.

For Battleground, Pirosh made his fictitious company part of the 327th Glider Regiment -- you can tell by the playing card Club symbol stenciled on their helmets. And while I wouldn’t say Battleground was completely and historically accurate, it commits no great sin against history -- with the only real dramatic liberty being the inclusion of the German saboteurs of Unternehmen Greif (Operation Greif), where English speaking Waffen SS commandos dressed in stolen GI uniforms infiltrated behind enemy lines to sew confusion and raise havoc by changing road markers or destroying ammo dumps, fuel stores, and bridges like the one Layton inadvertently gave directions to. And while the defenders of Bastogne were made aware of these spies, and adjusted daily passwords accordingly, using gutter slang or sports terms to trip up the enemy, none of these covert operatives ever made it that far south during the Bulge.

Beyond that, the production would strive for accuracy as the action sequences were staged as authentically as possible from the weapons used to the tactics deployed while implementing them -- right down to the pitch and whine of the mortars and the phlegmatic gurgle of incoming German 88 shells. This also included a recreation of the inclement weather, as temperatures hovered near 20-degrees for the duration of the offensive, with wind chill factors, freezing rain, ice, snow, fog and constant cloud cover rendering the Allied aerial advantage useless.

The cold, snow, and freezing drizzle raised all kinds of hell with men and equipment, which had to be constantly defrosted or de-iced, and frostbite and trench-foot became a bit of an epidemic and would account for 1/3rd of all casualties during the fighting. In the film, everyone complains when it starts snowing, except for Rodrigues, who had never seen snow up close before and starts dashing and sliding around, laughing his fool head off.

But as the storm worsens and the men start fortifying their foxholes with tree branches to try and keep things dry, Layton finds out that Bill Hooper's company is positioned nearby. He asks around but nobody's ever heard of Hooper until Layton says he was one of the new replacements. Here, he gets a thanks from the other company’s commander, who can now finish his casualty report. Seems the night before, Hooper's foxhole took a direct hit from a mortar -- "You don't hear it coming, and you don't know what hit you." And as Layton bemoans that they didn't even know his friend’s name, he is curtly told in the bloody aftermath they couldn't even find the man’s dog-tags.

Thus, a dejected Layton returns to his squad, just as Holley’s latest attempt to cook those eggs is thwarted yet again when he, Rodrigues and Jarvess are ‘volunteered’ to go out on a patrol. Here, Kinnie reveals Regimental Intelligence (G2) have reports that a pack of German infiltrators wearing GI uniforms might be hiding in a certain patch of woods after capturing and questioning two of them after they blew up a bridge near Neu Chateau. Realizing that must’ve been the patrol they let through the night before, Holley stops Layton from revealing this fact to cover their asses.

Before the patrol heads out, the squad suffers their first casualty when Staniferd is sent back to the aid station when his weather-induced pneumonia worsens. When Kipp complains that nothing like that ever happens to him, Bettis pointedly reminds him about that time in Holland when the malcontent, after finding out about a regulation that said you needed at least six teeth to stay on the line, busted his dentures and was given a two week reprieve until they got replaced. Kipp, of course, denies this, saying he knew of no such regulation and just “accidentally ran into a tree in the dark.” Then, as the three ‘volunteers' prepare to head out, they hear an incoming mortar barrage and dive for cover. Here, the squad suffers its second casualty when Holley's eggs take a direct hit.

Then, as the bombardment continues and picks-up in intensity, the jumpy Bettis finally loses it and runs away. Knowing full well he should have been pulled-off the line long ago for combat fatigue, Walowicz lets him go, hoping Bettis makes it back to the relative safety of the rear. Sliding back into their foxhole, with shells falling and detonating all around them, Layton makes sure over the cacophony that Walowicz knows who he is in case one of them finds him like with Hooper. But the Sergeant says he knew his name all along and offers a cigarette. This time Layton takes it, inhales deeply, and hunkers down further.

When the barrage lifts at long last without any further casualties, after digging out, that delayed patrol finally gets underway. And as they grumble about the size of the woods that only three men are supposed to search by themselves, Holley says it's just G2 strategy: if they don't come back, they'll know the Germans are in there. Meantime, Rodrigues hints at goofing off, and to just head back and report they heard voices talking in German. But Jarvess, who's had enough of regimental intelligence officers, says they should go back and say they heard Japanese voices and let them figure that one out.

When a jeep approaches, they challenge the occupants at gunpoint. And while the others do know the password, Holley, burnt once already, isn't convinced and thinks they're Germans. This tense stand-off continues until they start asking trivial questions that only a real American would know, like what a hot-rod is, or who Betty Grable is dating. Once that's settled they let the jeep pass and head into the target area, where they bump into another American patrol who claim these woods are empty of Germans. They seem congenial and know the password, but then Holley recognizes the Lieutenant from the night before.

Playing it cool, he slowly herds the other two back toward the road; but once they're out of earshot, he tells Rodrigues and Jarvess to haul ass because those guys were really Krauts -- who also realize they've been made and open fire. As all hell breaks loose, Holley loses both his helmet and rifle when the butt is shattered by enemy fire, but Rodrigues manages to take out their machine-gun nest with a grenade.

Continuing to fight their way out of the forest, the men come to a clearing where, after a little brutal hand to hand combat, they spot enemy tanks on the move. Suddenly, Rodrigues is hit and hit badly. They can't move him, so Holley and Jarvess hide him under a wrecked jeep but promise to come back for him with reinforcements. But when Holley and Jarvess report in, instead of sending a rescue party, an artillery barrage is ordered by the brass to try and neutralize those tanks they spotted.

Alas, the jeep they hid Rodrigues under is right by a farmhouse that the artillery unit has zeroed in on, so when Kinnie says to have Walowicz send out a patrol to retrieve Rodrigues once the barrage lifts, Holley angrily asks for a sponge because that's all they need to sop-up what's left of him. And the hits keep on coming as Walowicz won't be sending anyone on patrol because the man was badly injured in the last enemy barrage. And as they help load him onto a jeep to be evacuated, he gives Holley his helmet, rifle, and command of what's left of the squad. In the distance, they hear the American barrage start-up and Holley's first duty as squad leader is to break the news about Rodrigues to Pop Stazak.

Despite the worsening weather and the constant artillery barrages, Pop keeps after Holley to go and get Rodrigues. When Holley asks for volunteers, Pop, Jarvess and Layton step-up; the latter joking that maybe they'll find more eggs. As they head out, the men spy Kipp looking in a snowbank for his false teeth, which have mysteriously gone missing, and then Holley rips him a new one, saying he hopes it's warm where he's headed. Finding the wrecked jeep relatively intact, the hopeful rescue party starts digging out the accumulated snow that drifted around it -- but those hopes are soon dashed; they were too late; Rodrigues has bled to death.

But there is little time to mourn. And as the days pass and the siege grinds on, Jarvess manages to get his hands on a slightly outdated copy of Stars and Stripes, which finally reveals where Bastogne actually is among the details of the “heroic stand” they’ve been making. But the news isn’t all good as the latest on the weather shows the cold and snow will continue to ground any and all relief operations by the Air Corps for the foreseeable future.

Things continue to get worse when a limping Kinnie, his feet nearly frozen off, brings word that their entire field hospital -- doctors, medics, supplies, and the wounded, including Walowicz and Staniferd, were captured by the Germans. But he does have one good piece of news: Pop's official discharge papers have finally caught up. But when Pop starts to make his goodbyes, Kipp shows up, sporting his false teeth, and tells Pop he ain’t going nowhere because word just came down the line that Bastogne is now completely surrounded and cut off. Thinking this is a bad joke, Pop pops the little runt in the mouth but Holley and Layton pull him off, realizing Kipp must be telling the truth or his GI-teeth would still be “missing.”

Thus and so, surrounded, frozen, starving, and deathly low on ammunition, the Third Platoon is moved once again to guard a railway bridge, where they dig in for a relatively quiet night but are then violently ambushed the next morning. After their sentry is killed, the men stare into the impenetrable fog all around them. Unable to see the enemy, Hanson is the first to move and blindly fires into the nearby trees at a loud German voice, triggering a huge firefight. Hanson is hit, but Kipp takes up his position and continues the suppressing fire. Meanwhile, Holley, fear in his eyes, freezes, then panics, and then runs away from the battle...

While Battleground was still in pre-production at RKO under its nom de plume, Schary had already penciled in Robert Mitchum, Robert Ryan, and Bill Williams to play his squad before the plug got pulled. And so, when the production moved to MGM, he had to start over.

Initially, it was reported that Robert Taylor, Keenan Wynn, Van Johnson and John Hodiak would take the primary roles of the squad. But Taylor wasn’t really all that interested in doing an ensemble piece, saying he wasn’t right for the part publicly but really felt at this stage of his career he’d earned a solo starring vehicle; and to those ends, he managed to get released from the production to take the lead in the Sam Wood western Ambush (1950), which, in hindsight, might’ve been a tactical mistake. Wynn also bowed out, leading to some reassigning of roles at the top, while the rest of the cast would be rounded out by several MGM stock players, including George Murphy, Ricardo Montalban, Bruce Cowling, James Whitmore, Jerome Courtland, Don Taylor, Herbert Anderson, Douglas Fowley, and recent Universal cast-off, Marshall Thompson.

Once the cast was set, Wellman sent them all to boot-camp for some basic training. Most of the actors were already veterans, having served in the war in some capacity. Taylor was in the Army, Whitmore a Marine, and Fowley had served in the Navy in the south Pacific, where he’d lost all of his teeth from an explosion when his aircraft carrier took a hit. And like with The Story of G.I. Joe, where that production secured the use of 150 infantrymen from the Army as extras, all veterans of the Italian campaign, currently undergoing retraining to be redeployed in the Pacific (-- many of whom were killed during the Battle of Okinawa, where Ernie Pyle was also killed not long after filming wrapped), Battleground enlisted the use of 20 paratroopers from the 101st, all veterans of Bastogne, to help train the actors and serve as extras in the film.

Each primary cast member was assigned a paratrooper for the two weeks of training on MGM’s back-lot, where they were schooled in the use of firearms, tactics, and close order drills. Wellman also wanted the cast to learn the proper lingo and slang -- which went as far as the censors would allow, striving for authenticity and making it sound more natural.

Wellman always excelled at bringing a sense of camaraderie to his films -- be it between cowboys, burlesque dancers, or soldiers. And while the characters that comprised the squad in Battleground are typical in terms of types, they’re also a little atypical of the genre, too, thanks to Pirosh’s experiences and the Wellman touch.

Here, there is no good old boy from Texas, no Brooklynite wondering how ‘dem Bums were making out, nor any hot-blooded Italian lovers. Instead, we have a well-seasoned veteran everyone refers to as Pop; a Latino from Los Angeles; an idealistic columnist who bought-in early on why we should be fighting this war against fascism but is now having second thoughts; a yokel from Appalachia; a malcontent everyone would like to punch in the face; a paranoiac who’s convinced every bullet has his name on it; and the new guy. Not necessarily all likeable -- I mean Kipp is a turd, Jarvess comes off as a stuck-up asshole at times, and Bettis seems way too preoccupied with getting himself wounded to get off the line, but each fallible part is integral to make the squad a functional whole.

These are not caricatures, but characters -- from Pop’s arthur-itis, to Spudler’s constant yodeling and his non-regulation clod-hoppers, to Hanson’s coveted watch and his inability to shift time-zones, to Kipp’s constantly rattling false choppers, to First Sergeant Kinnie looking like a Bill Mauldin cartoon that crawled right off the pages of Stars and Stripes and started barking orders.

Whitmore was a late addition to the cast, who took over the role of Kinnie after James Mitchell was fired off the picture. Seems Mitchell couldn’t shake his image as a dancer to fit the grizzled role. In a later interview, Whitmore admitted that he did, indeed, base the look and attitude of his character on Mauldin’s Willie and Joe cartoons, which made the artist almost as revered as Pyle during the war. (I highly recommend Mauldin’s illustrated autobiography, Up Front.) And with these efforts, despite only having about a dozen lines, Whitmore kinda steals the whole movie, which netted him a well-deserved Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.

And then there’s Holley. Sadly, one of the few complaints people often raise about Battleground usually zero in on Van Johnson’s performance. Like with Whitmore, Johnson was bumped-up into the role when Taylor bowed out -- making one wonder if he was originally supposed to play the replacement, Layton? And like with James Mitchell, Johnson was known mostly as a second banana, song and dance man at MGM until his big breakout in A Guy Named Joe (1943). During the production of that film, Johnson fell victim to a horrific automobile accident that left him with a fractured skull, several facial scars, and a metal plate in his head. The producers wanted to replace him and finish the picture, but Spencer Tracy had taken a liking to his co-star and pulled some strings, delaying shooting for four months while Johnson recovered.

Classified as 4-F due to the extent of those injuries, Johnson was exempted from serving during the war. Thus, he was able to fill a vacuum left at MGM as their stable emptied out -- Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable and Mickey Rooney to name a few who served. Quickly promoted to a headliner, Johnson's first time as a lead was in the musical Two Girls and Sailor (1944) with June Allyson and Gloria DeHaven, which proved to be a big hit. He would co-star with Tracy again in Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), which chronicled the daring Doolittle bombing raid on Japan. He also joined an all-star cast for Weekend at the Waldorf (1945) and did several vehicles with Esther Williams -- Thrill of a Romance (1945) and Easy to Wed (1946).

In the run up to Battleground, Johnson starred with Judy Garland in the musical In the Good Old Summertime (1949) and got to stretch his legs a bit in the police procedural Scene of the Crime (1949), a rare film noir for MGM, which was one of the first features Schary green-lit as the new head of production as part of his edict that the studio needed to be making more realistic films to reconnect with audiences. And that's one of the beef's people have with Johnson's performance as Holley; that he doesn't seem to know what kind of film he's supposed to be making as he seems a little too eager with Denise and always appears to be mugging for the camera as he minces over those stolen eggs.

Pirosh had based this breakfast interlude on a real soldier from his unit, who had found a dozen eggs. But before he could cook them, Pirosh recalled, they were fired upon and the soldier took cover, careful not to damage the eggs. Here, Pirosh had to laugh, saying, “Remember, he was a seasoned veteran, and I was a replacement. But I figured that if he could worry about the eggs, then we were okay.”

And I honestly think people underestimate Johnson’s performance. Sure, in the beginning, he comes off as a bit of a loud-mouthed doof, and a bit of a goldbrick, making him the squad’s resident clown. When the men poke fun at Holley after he takes over the squad and starts giving orders, he quips back, "Yup, strictly chicken (shit), that's me." But you can tell, the weight of this responsibility is starting to wear on him. And without all that other extraneous stuff leading up to it, the scene where Holley reaches his breaking point, freezes under fire, and then runs from the fight, abandoning his comrades until Layton unwittingly stops/saves him, wouldn’t have near the impact that it has.

And to me, this is the turning point of the film -- not the climax when the fog finally lifts or the resulting air-drops, but the redemption of Holley, who, along with the rest of the squad, bent but did not break; and the outcome of the Battle for Bastogne (-- in the movie, anyways,) was never in doubt after that as Holley recovers and leads the counter-attack near the railway bridge.

See, thinking he was just trying to outflank the enemy, Layton springs after the fleeing Holley, who finally stops when Layton calls out to him, saying he’ll follow his lead. Here, Holley stops, gathers himself, gives a silent thanks to the young private when he isn’t looking, and then leads him into the surrounding forest. Kinnie spots them and orders the rest of Holley’s squad to follow. But while Jarvess charges out of their foxhole unscathed, Spudler, as he reaches for his drying boots, is shot and killed, crying for his mother as he expires.

Forming up with Holley and Layton, the others silently wait in ambush until the attacking Germans creep out of the fog. Now, with the tables turned, the enemy patrol is obliterated -- one of them also crying out for his mother in a nice, humanizing touch.

After the skirmish ends, Kinnie sends Holley and what's left of the squad back to Bastogne with the injured Hanson and a few German prisoners for a much needed breather. Hanson is left in a makeshift hospital that must rely on liquor to medicate their patients. When a nurse gives Hanson a belt, Pop swears if she gives him another one like that he's gonna go out and get himself shot. Later, while scrounging around for some dry clothes, Bettis finds them and offers some hot chow. Seems he's been working with the field cooks since his crack-up, but the others aren't listening to his story or really don't care.

After this brief respite, the men return to the line, taking up a position in a shelled out barn, where Jarvess shares some intel he’d gathered, explaining to the others where they are and what their defensive objective is by drawing a makeshift map in the snow -- until they’re interrupted by a small German envoy, who approach under a flag of truce. And while the German officers are blindfolded and hauled off to company headquarters for a palaver with the commanding officer -- in this case, General Anthony McAuliffe, Jarvess interrogates the rest of the patrol, trading a few cigarettes to learn the Germans are there to ask for their unconditional surrender. When the officers are returned, they are still confused by McAuliffe’s curt reply of “Nuts!” Told by their escort that it’s definitely a negative response to their request, the envoy beats feet back to their own lines.

This, of course, was based on an actual incident during the Battle for Bastogne, when, on December 22, 1944, an ultimatum was delivered to General McAuliffe, giving him two hours to surrender the city or face utter annihilation. At first, McAuliffe thought the Germans wanted to surrender. And when he was told, no, the Germans wanted him to surrender, as the legend goes, he answered, “Us surrender? Aw, nuts.” And as the legend continues, when the Germans demanded an official written reply to their ultimatum, unsure on how to respond, one of McAulliffe’s subordinates thought his initial invective would be perfect. And so, the General had it typed up and delivered and the rest is history.

Thus, the battle for Bastogne would continue. When Christmas arrives, the men attend a brief, multi-denominational service held by a Chaplain (Ames), who offers words of encouragement but must wrap things up prematurely when the Germans start their relentless shelling again. Even Bastogne itself gets pasted by the Luftwaffe on almost a nightly basis, and everyone is starting to fray at the edges -- even Layton has turned sullen and bitter. Hell, things are getting so desperate the walking wounded, including Hanson, are ordered to draw rifles and get back on the line (-- I love the throwaway bit where Hanson instructs a member of the rear echelon on the intricacies of an M1 Garand and is told he’s not trying to sell the damned thing and to just show him how the rifle works); clerks, mechanics, and even the cooks are also ordered to take-up arms. And as Bettis starts to protest, his KP takes a direct hit and he’s crushed and killed by the rubble.

Back outside of town, Kinnie receives word they're supposed to pull back into Bastogne but everywhere, on all sides, they see Germans -- they've been cut off. And as the enemy starts closing in on them, Layton takes aim but Kinnie stops him, saying to save his ammunition because, “They'll be getting a lot closer. And we'll still be here."

With that, as the men solemnly affix their bayonets and wait, Kinnie moves from hole to hole to encourage his men until he suddenly stops; he’s noticed something he hadn’t seen for quite awhile -- his shadow cast on the snow. Here, Kinnie quickly turns around and looks up and sees the sun has finally broken through the clouds.

The inclement weather pattern has finally dispersed, and the rough and tumble Sergeant can hardly contain himself. Then suddenly, as if to answer all their prayers, the Allied Air Corps sweeps into action, flying bombing sorties over the enemy and air-dropping countless supplies. And as the men deliriously gather up the food and ammunition, Holley bumps into and happily reunites with Hanson.

With the tide of battle now turned, the German's are soon on the run. Along with the air support, Patton's tanks have finally managed to break through to relieve the beleaguered defenders of Bastogne. And as Holley and the other battered survivors watch those tanks roll in, what's left of the Third Platoon is formed up.

Tired, battle worn, and most of them injured in some capacity, Kinnie gets them moving but this rabble is a far cry from what we saw at the beginning of the film. Spotting a relief column marching toward them, Kinnie starts barking at them to shape up. This they do, and despite their appearance, these men proudly march off to parts unknown. This battle may be over, but the war has yet to be won.

While he was shoring up the script for Battleground, Pirosh had several conversations with General McAuliffe, who was apparently ecstatic that the proposed film would be strictly told from the grunt’s point of view. “Who cares about generals,” said McAuliffe, “except for other generals and their families?” In fact, said General specifically requested that he not even be mentioned in the movie at all. But I believe McAuliffe still gets one namecheck in the film, by Kinnie, early on to dress down Holley over an order to move out. But beyond that, aside from the Platoon’s green Lieutenant Tiess (King), officers are remarkably absent from the film.

Pirosh and Wellman

Pirosh would also serve as an associate producer and technical advisor on the film, who pushed hard for that accurate portrayal of those gravel-agitators and foot-sloggers in the infantry (-- or grounded paratroopers); the hurrying up and waiting; the digging in and then instantly moving again; the constant complaining about the brass; and the lack of information as you head down in rank as to where you are and where you're going; and the shunning of replacements -- not necessarily because they hadn’t proven themselves yet, but because the wary veterans hesitated to make any new friends when in all likelihood they would be dead by the next day. And he kept pushing these points on Wellman, along with insisting the uniforms weren’t filthy enough and needed to look like they’d been slept in for over a month, that Pirosh finally crossed a line somewhere and the director had him banned from the set.

Pirosh was heartbroken over this, and Schary would try to make it up to him by essentially giving him full control over his next feature, Go for Broke (1951); another true-life docudrama based on the all nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which was made up of Japanese-Americans recruited from the internment camps, which went on to become one of the most decorated outfits of World War II.

Pirosh would write and direct Go for Broke!, but he would still leave MGM soon after; and yet, he would run into similar problems at Paramount with Hell is for Heroes (1962); another war film he wrote, produced, and was supposed to direct; but after several heated clashes with his temperamental headliner, Steve McQueen, Pirosh was fired off the picture and replaced by Don Siegel. Not long after this departure, Pirosh decided to switch mediums and approached Selmur Productions about a proposed TV-series based on frontline infantrymen, which hit the airwaves as Combat! (1962-1967).

Meanwhile, Schary and Wellman managed to bring in Battleground nearly three weeks ahead of schedule and over $100,000 below its estimated $2-million budget. Most of the outdoor action took place on sound-stages, but to the filmmakers credit this is never a distraction. Schary and production designer Hans Peter mapped out and built twenty-five indoor set-pieces of varying terrain -- all impressive, that Wellman and Vogel could film from several different angles to maximize locations. Most of the outdoor scenes were filmed in northern California and Oregon as the production chased the snow. And the final scene with the tank column was filmed near Fort Lewis, Washington.

And it was while filming on location that George Murphy suggested his character should gather up the propaganda leaflets dropped by the German planes during the Christmas ceasefire and walk off into the woods, his intention clear to use them for toilet paper. Here, Wellman apparently threw up his hands and shouted, "I finally got a good idea from an actor!" This not-so-subtle scene was subtle enough in the finished film that it slipped by the censors. Odder still, the only real problem the film had with the production code was the use of the words “Nuts” as the response to the demanded surrender, feeling it was inappropriate even though it was historically accurate. Luckily, saner heads prevailed and the infamous epitaph stayed in.

It's strange, really, how not only does history repeat itself but how we, as a species, tend to learn nothing from this endless cycle and keep repeating the same mistakes over and over again. And that goes for movie moguls, too. See, back in the 1920s, producer Irving Thalberg faced the same kind of resistance from his boss -- you guessed it, Louis B. Mayer, while trying to get The Big Parade (1925) made for MGM. Seems even back then Mayer felt no one would be interested in paying to see a war picture so soon after World War I had ended either. He was wrong then, too, of course, as The Big Parade would prove to be a huge hit -- thanks to Thalberg's persistence and perseverance.

Some 25-years later, the production of Battleground would not only prove to be another one of Mayer's massive misjudgements but would also, essentially, spell the end of his long and storied/notorious career. The old Hollywood studio system was already starting to crumble with the advent of the Paramount Decree in 1948 -- a legal ruling which severed the ties between the studios and their exclusive theater chains for exhibition; the very same year Nicholas Schenk and Mayer lured Schary to a floundering MGM. And yet, the only reason Mayer allowed Battleground into production at all was that he felt it would fail and teach his new head of production a valuable lesson: that he was always right.

Thus, you can kind of sense Mayer's hand in the nonsensical promotional and advertising material for Battleground, which really played up the minor character of Denise, making the film seem more like a raucous romantic comedy extravaganza than the sobering drama Schary, Pirosh and Wellman had intended; more like an MGM picture; more like a Mayer picture.

But when the film was finished, before it was released to the public, Battleground had a private screening at the White House for President Truman. Also in attendance was General McAuliffe. Both agreed that Schary and company had a bona fide hit on their hands. And so, as all the talk of Schary's Folly quickly dried up, Battleground hit theaters and struck a chord with audiences despite Mayer's purposeful misdirection and became a box-office hit -- in fact, it was easily MGM's biggest moneymaker of the last five years. Critics liked it, audiences loved it, and probably most importantly of all, veterans of the war liked and appreciated the film, giving it the ultimate seal of approval.

Mayer was no stranger to this kind of sabotage to knee-cap his underlings. And he and the rapidly promoted Schary would continue to butt heads over the next few years with Schenk caught in the middle. Things would finally reach a breaking point during the making of The Red Badge of Courage (1951), yet another war film that Mayer felt would fail; and this time he would take steps to ensure it failed, making it a doomed production from the get-go, which culminated with the heavily dickered-with and severely truncated film bombing at the box-office and the meddling Mayer being ousted from the studio he helped found back in 1924 when his 'either he goes (Schary) or I go" ultimatum to Schenk backfired.

And perhaps to add insult to Mayer’s injury, the folly of a film he had hoped would fail that eventually led to his downfall wound up being nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture for Schary, Best Director for Wellman, Best Screenplay for Pirosh, Best Black and White Cinematography for Vogel, Best Film Editing for John Dunning, and a Best Supporting Actor nod for Whitmore. Both Pirosh and Vogel would win their categories in a wide-open year at the Oscars as Battleground would lose to All the King’s Men (1949) for Best Picture, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s would take home Best Director for A Letter to Three Wives (1949), Harry Gerstad would get the nod for Best Editor on Champion (1949), and while I do love Dean Jagger’s performance in 12 O’Clock High (1949), Whitmore deserved it more for the anguished relief over the sun breaking through at long last alone.

But despite all those accolades and box-office receipts, Battleground has kinda fallen to the wayside a bit when discussing great war films, with folks usually championing Wellman’s leaner and meaner The Story of G.I. Joe over the MGM gloss (-- looking at you, Leonard Maltin). Really?

Yeah, no, I don’t think that’s really fair. And while I think both films belong in the conversation when discussing the best war films of all time, me, personally, would give the nod to Battleground. For I really do love everything about this movie -- the characters, the story, the action, and it's beautiful craftsmanship.

I love how this film doesn’t soft-soap the horror and stress of combat and what it tolls both physically and emotionally on an individual level. I love the paternal relationship between Pops and Rodrigues, a respect for your elders, and the interlude where they discuss the price of a phone call from New York to Wichita and from Wichita to Los Angeles. I love the scene where Holley and Layton argue over why they’re fighting for “Mom’s Blueberry Pie” instead of crab-cakes and beer. I love it when Jarvess reads about the fluffed details of their heroic stand and Holley says to skip the commercial. And, yes, I even love it when that little rat-turd Kipp rattles and pops his false teeth. Hell, I just love how these men were fighting to just stay alive, and to keep the guy in the foxhole next to him alive, until they could all finally go home.

I mean, take a look at the complete transformation of these characters from the clean-cut, snap-to drilling sequence at the beginning of Battleground, to the half-frozen, battle weary, starving, dirty, and exhausted shells of their former selves at the end. It’s both shocking and startling.

And

with the battle finally over, as they line up to march out, we also notice how much smaller the platoon is. Over half the men are

gone. And

as they start to shuffle off, haphazardly at first, until Kinnie snaps

them back together, they form-up in cadence, despite all they've been

through and endured, a defiant chorus bellowing as they march off into the

sunset, tall and proud.

I tell ya, it brings a tear to my eye and a rush of endorphins down my spine every single time I witness it.

Originally published on December 12, 2003, at 3B Theater.

Battleground (1949) Loew's Incorporated :: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) / P: Dore Schary / AP: Robert Pirosh / D: William A. Wellman / W: Robert Pirosh / C: Paul Vogel / E: John D. Dunning / M: Lennie Hayton / S: Van Johnson, John Hodiak, Marshall Thompson, Ricardo Montalban, George Murphy, Jerome Courtland, Don Taylor, Bruce Cowling, Richard Jaeckel, Douglas Fowley, James Whitmore, Brett King, Leon Ames, Denise Darcel